For more than twenty years, Clive Barker was terrifically prolific. During that period, a year without a new novel by the author seemed—to me at least—incomplete. Sadly, when Barker started work on the Abarat, that was that. Since the first part of the series was released in 2002 we’ve seen, for various reasons, just two sequels and one short novel in the form of Mister B. Gone.

That may change in 2015 with the belated publication of The Scarlet Gospels: a return to Barker’s beginnings by many measures. A sequel, indeed, to one of his very earliest novellas—no less than The Hellbound Heart, which found fame later when it became the basis of the film Hellraiser. Before that, though… this: an amoral meditation on humanity’s spiralling history of violence which certainly whet my appetite for more from the man who helped define dark fantasy.

Chiliad, to be sure, is neither a novel nor new. Rather, it is an arrangement of two tales intertwined with a maudlin metatext about an author who has lost his voice, and though its relevance today remains great, both “Men and Sin” and “A Moment at the River’s Heart” were previously published in Revelations, the Douglas E. Winter-edited anthology of short stories intended to celebrate the millennium.

That said, the overarching narrative seems particularly prescient here, at this point in Barker’s career. We find our unnamed narrator mid mid-life crisis, having forsaken all his old haunts and habits because of a bone-deep despair; a hateful malaise that says, to paraphrase: all he had in his life, and all he had sought to make, was worthless.

But at the river, things are different. At the river, contradictory as it is, something like a vision hits him:

Tales had kept coming even in the chasm, like invitations to parties I could not bear to attend, cracked and disfigured as I was. This one, however, seemed to speak to me more tenderly than the others. This one was not like the stories I had told in my younger days: it was not so certain of itself, nor of its purpose. It and I had much in common. I liked the way it curled upon itself, like the waters in the river, how it offered to fold itself into my grief, and lie there a while if necessary, until I could find a way to speak. I liked its lack of sentiment. I liked its lack of morality.

These lacks become apparent in both “Men and Sin,” which describes the journey of an ugly man called Shank to avenge the brutal murder of his partner Agnes, and in “A Moment at the River’s Heart,” which has a husband set out to identify the killer of his beloved wife, who “had met death by chance, because she had wandered its way.”

There are surprises in store in both stories; twists, if you will, but Barker, to his credit, deploys them deftly, and in the interim the two tales relate to and engage with one another in various ways. They and their characters and the violence that befalls them all are joined—at the lip, if you will—by the river. The same river that inspires the framing tale’s narrator; the same river that runs through the changed landscape of his paired parables, which—though there is a thousand years between them: a chiliad, in fact—take place in the same location.

In my mind, the river flows both ways. Out toward the sea, toward futurity; to death of course, to revelation, perhaps; perhaps to both. And back the way it came, at least at those places where the currents are most perverse; where vortexes appear, and the waters are like foamy skirts on the hips of the rocks. […] Don’t trust what you hear from shamans, who tell you, with puffy eyes, how fine it is to bathe in the river. They have their mutability to keep them from harm. The rest of us are much more brittle; more likely to bruise and break in the flood. It is, in truth, vile to be in the midst of such a commanding torrent: not to know if you will be carried back to the womb—to the ease of the mother’s waters—or out into cold father death. To hope one moment, and be in extremis the next; and not to know, half the time, which of the prospects comforts and which arouses fear.

The thousand years that separate the stories simply melt away in the final summation, revealing two torrid tales about the cruelty of creation; about what it gives, only to take away.

You know what happens next. The parable is perfectly transparent. But I have to tell you; I have to believe that my meaning resides not in the gross motion of the tale, but in the tics of syntax and cadence. If not, every story may be boiled down to a few charmless sentences; a sequence of causalities: this and this and this, then marriage, or death. There must be more to the telling of stories, just as there must be more to our lives.

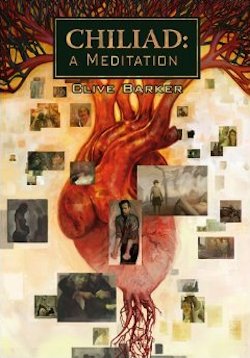

As above, so below—for there is so much more to these stories. Packaged as a pair as opposed to the extended parentheses they represented in Revelations, both “Men and Sin” and “A Moment at the River’s Heart” are given a second lease of life, and indeed death, in this terrific new edition. Hauntingly illustrated by the Mistborn trilogy’s cover artist Jon Foster, whilst the author plays his own artful part perfectly, Chiliad is as cold as it is contemplative, and as cerebrally thrilling as it is viscerally chilling.

Welcome back, Clive Barker.

Chiliad is available January 28th from Subterranean.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.