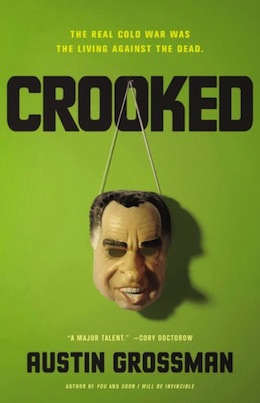

Austin Grossman’s new novel, Crooked, features a very different Richard Nixon from the one you may remember from history class. To illustrate, allow me to start this review with a brief quote from the book’s opening chapter, showing Nixon in the Oval Office:

I closed the blinds, knelt down, and rolled back the carpeting to reveal the great seal of the office, set just beneath the public one. I rolled up my left sleeve and cut twice with the dagger as prescribed, to release the blood of the Democratically Elected, the Duly Sworn and Consecrated. I began to chant in stilted, precise seventeenth-century English prose from the the Twelfth and Thirteenth Secret Articles of the United States Constitution. These were not the duties of the U.S. presidency as I had once conceived of them, nor as most of the citizens of this country still do. But really. Ask yourself if everything in your life is the way they told you it would be.

Well, the man has a point.

Crooked is the story of Richard Milhous Nixon, 37th President of the United States: the story of his rise through the political echelons, from a California House Representative and Senator to Vice-President during Eisenhower’s term in office and, finally, to the highest office in the land, from which he resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

But, as the above quotation probably suggested, Crooked’s Nixon is not the Nixon we know. Early on in his career, while he’s on the House Un-American Activities Committee—basically a government-led witch hunt for communists—he follows a suspected commie home. There, he stumbles upon a dark ritual, involving Russians summoning eldritch horrors from the beyond. You know, as you do.

I was thirty-five and I’d thought I was playing political poker and it turned out I’d been playing in some other game I didn’t even know about. Like I’d been holding a hand of kings and then the other people around the table started putting down more kings, a king with a squid’s face, a naked king with goat’s horns holding up a bough of holly. A Russian king with an insect’s voice.

It turns out that the real danger to the homeland isn’t so much actual communism as, well, you’ve read Lovecraft right? There’s a separate arms race happening, aside from the nuclear one we all know and love: both sides in the Cold War are busily pursuing all kinds of paranormal powers and invoking monsters from the dungeon dimensions. You know that line from Myke Cole’s (excellent) Shadow Ops series, “magic is the new nuke”? Like that. Russians and Americans aren’t just trying to build the biggest bomb; they’re also trying to summon the biggest, meanest shoggoth.

However, don’t mistake Crooked for just another Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter clone. Instead, Grossman delivers an in-depth character study of a complex, tortured man. Nixon, filled with self-loathing and driven to pursue power, is a lonely soul with a powerful gift for bare-knuckles, take-no-prisoners power politics. Add to that his knowledge of the great secret—a line of American presidents stretching back in time guarding the country’s dark magic—and you get a memorable anti-hero:

Because I never did a thing that wasn’t somehow touched with selfish, furtive hunger, with a private, annihilating need for recognition. Because I’m a child in a fairy tale cursed from birth, and there has never been anything I can put my hand to without tainting it, no triumph so great or solemn that it doesn’t turn spoiled and ridiculous. Because, sooner or later, the darkness always gets in.

Nixon reminded me in some ways of David Selig, the main character of Robert Silverberg’s brilliant 1972 novel Dying Inside. Selig is a bitter, misanthropic man who is slowly losing his telepathic gifts, which never did him much good anyway: he never used his power for good, was never able to make a true connection with other people, and mainly used his gift to further his own good. Dying Inside was published during the Nixon years, and I like to think that, if this fictional Nixon would have read Selig’s story, he would have recognized a spiritual brother of sorts.

If there’s one issue I have with Crooked, it’s the odd dissonance between Nixon’s tortured character and the comparably chipper way the Cthulhu-esque beings and powers are described. Partly, this is because we rarely see any of them in action; instead, there are mostly secondhand reports, sometimes written in the dry legalese of a political memo and once, memorably, even in bullet points:

Not all military elements will be vulnerable to nuclear weaponry or associated effects such as radioactivity, kinetic shock, and firestorms. Potentially nuclear-resistant entities, domestic and foreign, should be accounted for in any postconflict planning scenarios.

These include:

(a) Corn Men

(b) Entity code Raven Mother and attendant fragments/hybrids

(c) Exofauna of Baikonur region

(d) GRU command elements above the rank of colonel, who are reputed to be experimentally radiation-hardened by hybridization, grafting, and injection with tissue samples from various archaic and exoplanar fauna

(e) Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

(f) Unidentified Dyatlov Pass survivor

(g) The British royal family

(h) Little Hare, a Native American trickster god of the Southwestern United States

Intentional or not, there’s something comically absurd about these dry depictions of the gibbering terrors beyond the veil. I admire that Grossman didn’t go for blood-and-gore horror shock, but maybe a touch of this would have given Crooked some more impact. Combine this with some distinctly slow pacing across the middle of the novel—happily resolved when Henry Kissinger finally comes on stage—and you’re left with a clever concept and a fascinating character, but unfortunately not always the most thrilling story.

Still, I’ll never be able to hear the name Richard Nixon again without thinking of Crooked. Austin Grossman’s three novels to date have all been hugely different from each other. I can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.

Crooked is available now from Little, Brown and Company

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. You can find him on Twitter, and his website is Far Beyond Reality.