Last Tuesday, the Library of America released The Complete Orsinia—a gorgeous, special edition hardback that collects Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Orsinia” works. Le Guin is one of a handful of sci-fi authors to be featured in the mostly ‘literary’ collection, taking her place among the usual crowd of male luminaries (Dick, Lovecraft, etc.). And yet the novel Malafrena (begun in the 1950s, but published in 1979) and its accompanying short fiction and songs (originally published 1976 and on) don’t feature the alien worlds or strange technologies that Le Guin’s more acclaimed works do. In fact, the novel’s traditional homage to a European coming-of-age novel will sound nostalgic, maybe even backwards to some readers, compared to the complex, feminist visions of her sci-fi. However, the hallmarks of the Hainish Cycle and Earthsea remain: the strangers in strange lands, the struggles for social change, and the perils of identity-making, all weave their way through the stories of Orsinia. As one of Le Guin’s first worlds, Orsinia is in many ways a precursor to the more fantastical ones that followed. Moreover, its more explicit relationship to classic literature might make you view both genres in a new light.

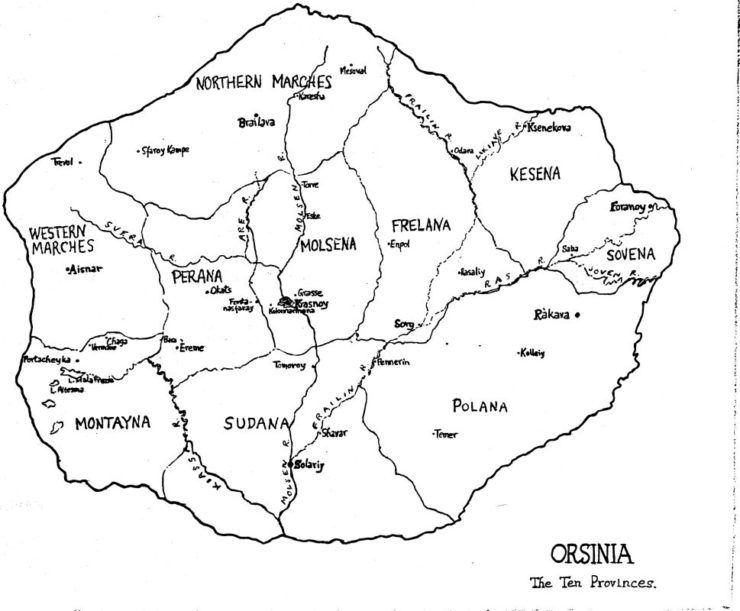

And, of course, there’s the fact that Orsinia—the European country where each story is set—is imaginary. “I knew it was foolhardy to write fiction set in Europe if I’d never been there,” Le Guin explains in the collection’s introduction. “At last it occurred to me that I might get away with it by writing about a part of Europe where nobody had been but me.” Thus with a characteristically deft hand, and an edge of the uncanny, Le Guin explores the boundaries of a place and time at once familiar and foreign.

“–Europe, stretched like the silent network of liberalism, like the nervous system of a sleeping man–”

Malafrena, the novel that makes up the bulk of the collection, is told in the style of a 19th century bildungsroman. Drawing from the influences of novels like Stendhal’s The Red and the Black and Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, it follows a provincial bourgeois upstart named Itale Sorde as he leaves his idyllic, privileged life in the mountains to find freedom in Osinia’s capital, Krasnoy. Naive and passionate, Itale is a charming vision of the Enlightenment-era revolutionary: all optimism and classical allusions, Rousseau without the trepidations of the Terror. Away from home, he faces every manner of challenge: poverty, cruel and distracting mistresses, and corrupt politics among them. The tone, though, is set by his longing for home and his inability to return. Through shifting points of view–to female characters in particular–the novel also shows us Itale from the outside: an obstinate and privileged young man, who must learn and unlearn every definition of freedom before he can address the people he left in his wake.

Malafrena is not, I think, simply historical fiction (though it is, of course, also that). It is an imitation of a specific historical form of writing—which is to say, it reads less as a novel about the 19th century, and more as a 19th century novel in-and-of-itself. For those acquainted with this era and style of literature, Malafrena treads familiar territory, and so in some respects, its references and tropes highlight the novel as one of Le Guin’s youngest and most derivative. In other respects, though, they illuminate the incredible world-building at play, Le Guin’s familiarity with form and history, and her subtle use of dramatic irony. The strangeness of reading a historical novel that is not, in the strictest sense, historical, is one of Malafrena’s greatest delights, and ties it all the more firmly to the rest of Le Guin’s oeuvre. Great too, will be the delight I’ll take in reading and rereading said oeuvre in relation to Le Guin’s obvious influence by that era of history and literature.

Similarly, the stories gathered in the Library of America collection are in turn fascinating, dull, imaginative, and rooted in realism. Many are contemporary, or at least recent, to Le Guin’s own life, and so lack the historical uncanniness I’ve described above. As a collection, though, these tales feel very much at home with Malafrena, deepening the cultural and historical landscape Le Guin laid out in the novel, and developing its gender commentary and general sense of optimism. “An die musik” and “The Fountains” stood out in particular as moving dedications to the power of art and place, and condensed the nostalgic, romantic outlook that made Malafrena so compelling. These stories are, perhaps, to be enjoyed piece-by-piece, when we’ve become homesick for the sublime mountains of Montayna or the bustling city of Krasnoy. Regardless of your opinion on Malafrena in relation to the rest of Le Guin’s works, you’ll no doubt feel connected to the world of Orsinia once it’s complete. Le Guin has, in this collection as a whole, the ability to immerse you entirely in a place, and to make her characters’ love for it your own.

I hope very much to see more of Le Guin’s works collected in the Library of America’s stunning editions. With accompanying maps, timelines, and notes, the collection has an air of weight and authority to it. Le Guin’s more fantastical works deserve much the same treatment, and will serve to highlight SFF’s place in the larger tradition of American literature.

The Complete Orsinia is available now from Library of America.

Emily Nordling is a student of 19th century revolutionary literature. She is a library assistant based in Chicago, IL.