Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

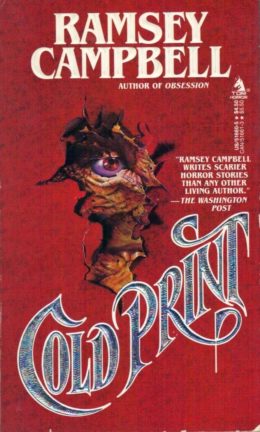

Today we’re looking at Ramsey Campbell’s “Cold Print,” first published in August Derleth’s 1969 anthology, Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Spoilers ahead.

“Grimacing at the books which stretched wide their corners like flowering petals, Strutt bypassed the hardcovers and squinted behind the counter, slightly preoccupied; as he had closed the door beneath its tongueless bell, he had imagined he had heard a cry somewhere near, quickly cut off.”

Summary

Sam Strutt has a yen for esoteric literature, although not the kind they read at the Esoteric Order of Dagon. I think. He’s a fan of Ultimate Press books, with titles like The Caning Master and Miss Whippe, Old Style Governess. Being a gym teacher allows him to exercise his proclivities in the much blander form of smacking errant students on the butt with a gym-shoe.

One slushy afternoon in Brichester, Strutt seeks books to ease him through the bothersome holidays. The first shop has nothing to his taste. However, an eavesdropping tramp promises guidance to one that stocks Adam and Evan and Take Me How You Like. Strutt’s disgusted by the grimy hand on his sleeve but agrees to follow the tramp to this promised literary paradise.

After refreshing himself in a pub at Strutt’s expense, the tramp tries to back out. Strutt’s temper flares, loudly, and the tramp leads on through dingy backstreets to a basement bookshop advertising “American Books Bought and Sold.” The dusty interior houses boxes of worn paperbacks: Westerns, fantasies, erotica. Strutt hears a cry choked off as they enter, a common sound in such neighborhoods. Dim yellow light seeps through the frosted glass door behind the counter, but no bookseller emerges.

The tramp’s anxious to leave. He fumbles a book from a glass-fronted case. It’s an Ultimate Press publication, The Secret Life of Wackford Squeers. Strutt approves and reaches for his wallet. The tramp pulls him from the counter, pleading for him to pay next time. Nonsense. Strutt’s not about to offend someone with Ultimate Press connections. He leaves two pounds and carefully wraps Squeers. Across the frosted glass moves the shadow of a seemingly headless man. Frantic, the tramp bolts, knocks over a box of paperbacks, freezes. Strutt pushes past the mess and out the street door. He hears the tramp scurry after him, then a heavy tread from the office, then the slam of the street door. Out in the snow he finds himself alone.

So what? Strutt knows his way home.

On Christmas Eve day, Strutt wakes from uneasy dreams. Even breaking one of his landlady’s glasses and grabbing at her impertinent daughter don’t cheer him up. He remembers the bookseller he used to patronize, who shared his tastes and made him feel less alone in a prudish and “tacitly conspiring hostile world.” That fellow’s dead now, but maybe this new bookseller would like to engage in the kind of, um, frank conversation that would really lift Strutt’s spirits. Plus he needs more books.

A bookseller with a head like a “half-inflated balloon” perched on a “stuffed tweed suit” admits him. Their friend the tramp isn’t around today, but no matter. They go into the office. Strutt sits before the dusty desk. The bookseller paces around, asks “Why d’you read these books?”

“Why not?” is Strutt’s reply.

Doesn’t Strutt want to make what’s in the books really happen? Doesn’t he visualize the action, like the bookseller who had this shop before?

The current bookseller fetches a handwritten ledger, which the former proprietor discovered. It’s the sole copy of the twelfth volume of Revelations of Glaaki, written under supernatural dream guidance. Like Strutt’s favored books, this too contains forbidden lore.

Strutt reads at random, with the odd sensation of being at once in Brichester and below the earth, pursued by a “swollen glowing figure.” The bookseller stands behind him, hands on Strutt’s shoulders, and indicates a passage about the sleeping god Y’golonac. When Y’golonac’s name is spoken or read, he comes forth to be worshipped, or to feed and take on the shape and soul of those he feeds on. “For those who read of evil and search for its form in their minds call forth evil, and so may Y’golonac return to walk among men…”

Strutt remembers his old friend’s talk of a black magic cult in Brichester. Now this fellow invites Strutt to be Y’golonac’s high priest, to prostrate himself before the god and “go beyond the rim to what stirs out of the light.” The bookseller who found Revelations received the same invitation. He turned it down and had to be killed. Then the tramp read Revelations by accident. He went mad “when he saw the mouths,” but the current proprietor hoped he’d lead like-minded friends to the shop, and so he did! Only he did it while the proprietor was feeding in the office. He’s paid for his imbecility.

Certain he’s alone with a madman, Strutt threatens to burn the precious Revelations unless he’s released. When he carries out the threat, the proprietor begins to–expand, ripping out of his suit. Strutt breaks the frosted glass of the locked office door; the act seems to isolate him, suspend all action outside himself. He turns to see a towering naked figure, headless like the shadow the previous day. This is happening because he read the Revelations! It’s not playing fair, he did nothing to deserve it!

But before Strutt can scream, hands descend on his face, cutting off his breath, and wet red mouths open in their palms.

What’s Cyclopean: Everyone else is dirty to Strutt: they “soil” him with hands “lined with grime”; meanwhile he’s “fastidious.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Strutt holds the entire world in egalitarian contempt; ethnicity doesn’t come up.

Mythos Making: Even the minions of Cthulhu dare not speak of Y’golonac. Maybe that’s why we haven’t heard about him before now. Along with the familiar Shub-Niggurath, Golly’s friends include Byatis, Daoloth, and the brood of Eihort.

Libronomicon: Our newest addition to the shelf of forbidden tomes is The Revelations of Glaaki, the Mythosian equivalent of dream-dictated New Age volumes like The Teachings of Don Juan. Also appearing in this story are various titles by Ultimate Press, which you probably won’t find in Miskatonic’s library but may find secreted under mattresses in the dorms.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The bum who brings Strutt to the fateful bookstore was driven mad by reading The Revelations of Glaaki. Fortunately for the author/transcriber, this makes him recommend the book to other people. Unfortunately for the author/transcriber, it makes him recommend that those people walk off without paying for their purchases.

Anne’s Commentary

If knowledge is power, and power can be dangerous, then bookshops and libraries must be among the most hazardous places on earth. It seems the danger, re: bookshops, increases in direct proportion to how out-of-the-way and dusty they are. Poor nasty Strutt stalks right into a trap at American Books Bought and Sold. (And is that a British thing, secondhand books from the United States? Not that all the offerings in this shop are American. The display window holds SF from Brian Aldiss and some French titles. Inside, besides the Westerns and Yankee porn, there are Lovecraft and Derleth, with Revelations of Glaaki tucked right at home between them.)

In his introduction to the collection Cold Print, Ramsey Campbell wrote that August Derleth encouraged him to shift his weird tales from Lovecraft’s fictional Massachusetts, and so he did, creating a Campbell country in the Severn River region of Gloucestershire, England. The Brichester of this week’s story is its principal town, complete with a tome-holding university less careful than Arkham’s Miskatonic, alas, for in the 1960s a Muslim student burned its eldritch collection to ashes. Revelations of Glaaki meets a fiery fate pretty often, it seems. Glaaki (or Gla’aki) itself is a Great Old One who fell to earth in a meteorite, creating the lake it subsequently inhabited. It resembles a giant slug with metal spikes or spines growing out of its body. The spines inject a toxin that renders targets undead slaves to Glaaki. Y’golonac, another Campbell introduction, is arguably even ickier, and perilously easy to summon. Speak his name or even read it, in he lumbers, probably hungry. I wonder, though, if the summons only works when the summoner pronounces it right, in which case maybe the peril’s not so great after all.

“Cold Print” is urban fantasy in its darkest shade of grimy gray. When I first read the story (in grade school), I was annoyed by the loving/loathing detail of its descriptions hey, just get to the monster! I didn’t get that Strutt himself was a sort of monster, for the S/M-B/D-pederasty elements were beyond my innocent understanding. Mostly. Now I’m fascinated by the detail lavished on an unbeautiful city snow storm and the dingy, dirty environment of the fastidious protagonist. Well, fastidious in his person, anyhow, and in the care of his personal library.

Now I’m older and wiser(ish), I find Strutt the most intriguing element of “Cold Print,” along with the city which is both the object of his revulsion and his reflection. He is one piece of work, all right, but as we traverse the story deep in his mind, party to his perceptions, he does earn a certain sympathy, doesn’t he, however grudging? We learn little of his backstory beyond his friendship with the Goatswood bookseller. Oh, except for that brief allusion to the scrawled forbidden lore passed around the toilets of his own schoolboy days.

Early exposure to pornography’s not unusual. It doesn’t twist every mind it touches. But Strutt’s obsession follows him into adulthood. He links sex and violence in an inextricable embrace, soothing himself with visions of white gym shorts stretched over students’ bottoms. When the landlady mishandles his books, he imagines her thrusting Miss Whippe into Prefects and Fags no, she forces Prefects and Fags to straddle Miss Whippe! His face needled by sleet snow, he longs to speak even to the tramp of how they harmonize in his ears, the sound of neighbors’ creaking bedsprings and the sound of the landlady’s husband beating her daughter upstairs.

He also consistently views women as both overtly sexual and mocking, unavailable (to him). Shopgirls watch him smugly as they dress headless mannequins (headless!). A buxom barmaid billows about, working the tap pumps “with gusto.” A middle-aged woman in a window draws the curtains to hide the teenage boy she must certainly be about to seduce. The landlady’s daughter twits him on his “fab Christmas” celebrations he tries to grab her to “curb her pert femininity” but she eludes him, skirt whirling. A mother apologizes when her child pelts Strutt with a snowball he sneers at her sincerity. The blank gaze of an old woman chills him; when he hurries on, he’s “pursued” by a woman pushing a pram filled with a litter of papers.

Strutt isolates himself. You can’t make friends nowadays, he thinks. But he still longs for connection, even if it can only be through frank discussion of his kinks with a sympathetic mind. Or through the “satisfying force” of a shoe brought down on a student’s butt.

I’m wandering on toward the question of whether Strutt’s right. Must his “evil” reading and “evil” imaginings summon the much greater evil of Y’golonac, headless god of perversity? Is Y’golonac unfair? Does Strutt really deserve his fate, either to serve the greater evil or be consumed by it? What are the metaphysics? Does every Strutt, by “speaking” Y’golonac’s name, create Him?

I’m going to wander and wonder on now. But along the way, I don’t think I’ll check out any new bookshops. I’ve already got a copy of Nicholas Nickleby and can read about whip-happy headmaster Wackford Squeers in the Dickensian original, and that’s bad enough.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“Cold Print” is a good example of a particular sort of horror. If you like this sort of thing, you’ll like this story. If you don’t like this sort of thing (as I mostly don’t), you probably won’t like this story. And indeed, I didn’t.

But Ruthanna, you say, don’t you like forbidden tomes, the mere reading of which exposes one to unthinkable fates? Don’t you enjoy exactly descriptive prose, with telling details that bring a setting to vivid life? Don’t you appreciate a perfectly captured mood that carriers the reader along from deceptively mundane opening to cosmically horrific close?

Well, yeah, I do like those things. And they’re inarguably present in “Cold Print,” and well-done, too. The thing I bounce right off from—a trope that authors keep using because plenty of readers do like it—is the nasty protagonist whose perspective we’re stuck with until he gets his comeuppance.

Strutt represents a truly banal sort of evil. It’s hardly even fair to call him evil—we know he’s a smug SOB and at least minimally a sexual predator. It’s not clear, though, that he’s ever worked up the courage to do more than grab the landlady’s daughter’s ass, or obsess over his low-quality porn while paddling schoolboys. He mostly wanders around stealing bus rides, feeling self-rightous about his “forbidden” “literature,” thinking he’s better than random street bums, and not bothering to call the cops on the child abuser upstairs. His brain is a sordid place to spend a few minutes, and by the end of the story I’m not so much rooting for him to get et as relieved that it’s happened and I can now go wash my hands.

He seems like he’d make a perfectly good cultist, but would probably drastically overestimate his priestly abilities. Either Y’golonac likes priests he can take down a peg, or the servant using the bookstore as a snack trap wants a priest it can keep under its toothy thumb. That’s an interesting option. Perhaps there’s all sorts of political intrigue going on among Y’golonac’s cultists, who look for smug, breakable mortals to add to their pawn collections while they plot and scheme with each other. And chow down on smut readers. The nice thing about having lots of mouths is you can trade witty banter and eat at the same time. I would happily read that story—sort of “Call of Cthulhu” meets Reign.

Y’golonac himself is interesting, and likewise the Revelations of Glaaki. The most fascinating excerpt is the claim that “when his name is spoken or read he comes forth to …feed and take on the shape and soul of those he feeds upon.” (Uh-oh. Um, sorry about the apocalyptic effects of this post?) That suggests the “servant” may be, at least temporarily, Y’golonac himself. “Long has he slept,” but we know from Cthulhu’s example that these things aren’t always as limiting as they should be. So the bookstore owner, and the bum, and now Strutt, are all shapes and souls that Golly can take on at will? This could get messy.

If he really wants to gain influence, though, Golly might want to look into better distribution for his books. Forget these sordid little adult bookstores, and go after some big chain stores. Maybe on one of those Special Holiday Sale tables up front. Just don’t specify which holiday you’re talking about, and you’re well on your way to world domination. Of course, the world’s due to be “cleared off,” so that might not be as useful as it sounds.

Next week, meet Randolph Carter’s shy twin and Harley Warren’s obnoxious older brother in Sarah Monette’s “Bringing Helena Back.” You can find it, along with other tales of Kyle Murchison Booth, in Monette’s collection The Bone Key.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.