Gormenghast Castle is hidden. When Titus Groan, the Earl of Gormenghast, finally escapes, he is shocked to find that no one has ever heard of it. The walls of his ancestral home that stretch for miles; the jagged towers and crumbling courtyards, the endless corridors, staircases, and attics, the weirdos and cutthroats who live there—it all goes unseen by the outside world. Whatever happens there happens in shadow and obscurity.

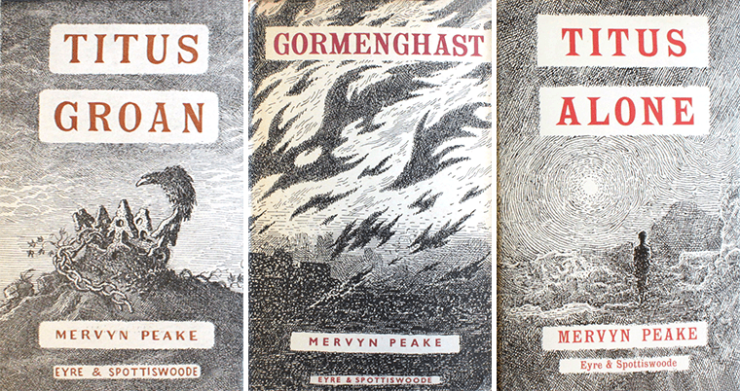

But all that might soon change. The Gormenghast books, in this moment of dragon queens and sword swingers, seem poised for a long overdue resurgence. November 17th marked the fiftieth anniversary of author Mervyn Peake’s death. That means his dark fantasy trilogy (Titus Groan, Gormenghast, and Titus Alone) is headed into the public domain this year, while a potential TV adaptation is swirling about, with Neil Gaiman and other notables attached.

Gormenghast is violent, creepy, escapist fantasy. There are burning libraries, hordes of feral cats, insane people locked away in long-forgotten wings, tall towers and dark dungeons. The story is a grisly yet whimsical affair: a power struggle unleashed by the machinations of a surly kitchen-boy. With its bleak moral outlook and macabre humor, the books are a brilliant match for contemporary appetites.

But anyone setting out to bring Gormenghast to TV ought to be wary… It was tried once before. A cheesy BBC effort from 2000 showed the potential difficulties of filming a Gormenghast that captures the feeling of Peake’s books, whose dense, poetical writing and cutting social satire is nearly the opposite of George R.R. Martin’s no-nonsense prose. Peake is a maximalist, given to long fits of description—there are shadows and sunbeams in Gormenghast that have more personality than some of Peake’s characters.

It isn’t surprising that a 1984 radio play written by Brian Gibley was more artistically successful, with Sting in the role of Steerpike. (Sting, with a horse, a dog, and one of his children named after characters in Gormenghast, is almost certainly the world’s most famous Peake fan.) At the height of his fame, Sting owned the film rights to the books and claimed to have written a movie script that never appeared, for better or worse.

Since then, the fantasy genre has only grown. Much like Christianity, it’s matured from a backwater cult into a full-blown cultural phenomenon, with tribes and nations all its own. The Guardian’s review of the 2000 BBC miniseries declared “this should be the perfect time to televise Gormenghast.” And The New York Times agreed: Peake fever was imminent. At long last, fantasy was fully part of the mainstream. And yet Gormenghast eluded fame then, and continues to occupy a marginal space even among fantasy buffs—despite the intermittent efforts of enthralled bloggers. Gormenghast’s coronation in the pop-culture pantheon is long overdue.

But Peake’s whimsical prose has always been a major hurdle for potential readers. Like Poe on acid, Peake will set a scene with torrents of gothic description—a four-page devotional to a minor character’s coughing fit or someone’s bout of drunkenness—and then shift in the very next scene to a tone of arch-irony worthy of Austen. Similarly, the thread of Gormenghast’s plot, while lush in some places, is hopelessly threadbare in others. Like Moby-Dick it is built largely from its digressions. It is not a story overly obsessed with action. There are no dragons roaming its halls. There are no spell-books, no heroes, and no magic. There are no zombies to slice and dice.

The story’s main preoccuptation is the castle itself: its society brittled by age, its highest offices becoming ever more remote from life, governing only themselves, torturing themselves with needless rites. Gormenghast is gripped tight by self-imposed strictures—by a social confinement so complete that the people in the castle are convinced that the outside world is literally nonexistent. Complete obedience to arbitrary values, internalized self-loathing, absolute power wielded to no particular end at all, a deterministic universe that refuses to acknowledge the individual psyche: compelling stuff! But, as Westworld has showed its viewers all too frequently, the grand problems of ontology are sometimes better left offscreen.

Making a good soup from the stock of Gormenghast will be a delicate process. The BBC adaptation chose to lean heavily on costumes and comic elements. But on the page, Peake’s outrageous sense of humor is always double-edged, paired with grotesquerie, pity, or spite. That is hard to film. And contemporary audiences may not take kindly to the books’ jabs at the amusing speech patterns of the lower class, or the way a person limps. Peake has a keen social imagination but he is a raconteur, not a moralist. Even his most generous readers can’t help but wince at the portrayal of the noble savages who live in the Outer Dwellings clinging to the castle walls, who are never allowed to be anything but proud and naively primitive.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Still, if Gormenghast is treated with too much gravity, it will look ridiculous. So much of the power of the books comes from Peake’s brutal irony and his refusal to take the plight of his characters too seriously.

One area in which Gormenghast is much stronger than the competition, however, is its brilliant antihero. Steerpike is a charismatic, ruthless schemer—a Macbeth untroubled by his bloody hands, talented like Tom Ripley and grimly competent in the manner of Deadwood’s Al Swearengen. The dramatic center of the castle, Steerpike has none of the vacuous evil of a Ramsay Bolton or a Joffrey Baratheon, none of the remoteness of Sauron. Steerpike is full of evil urges, and manipulation is as natural to him as breathing. But his crimes are tempered by his oily charm and righteous class resentment.

Born to a life of kitchen service, he acts boldly to cheat the system from within, gaining access to its highest ranks through sheer pluck, excellent timing, and some sturdy climbing rope. Steerpike sees his own advancement as a restoration of moral order, and he is only a villain because he isn’t particularly troubled with the means by which he restores it. He sees the injustice of his society, and that further obedience to its arbitrary moral facts will only hamper him. In a world of thoughtless obedience his greatest crime is that he dares to imagine equality of opportunity. He is a homegrown antagonist, raised in the castle’s ossified culture but ambitious enough to escape it. Why should he play by the rules of a world that sees him only and always as a servant—that refuses to acknowledge his capacities and his potential? He schemes to transcend the social confinement to which the heroes are thoughtlessly chained, but we are doomed to root against him. Peake, brilliant and cruel, shows us that we would rather preserve a rotten system than topple it.

In a way, Peake’s focus on structural injustice and moral luck might hamper a transition to TV. Westeros may well be a land lost to cynicism and ignorance, but Game of Thrones is obsessed with old-fashioned moral conduct, the quest to figure out right from wrong in a place overcome by casual evildoing. In the midst of senseless and exuberant violence, an endless winter of barbarity, there remains a dream of spring. The Starks will be avenged. The war will someday end. The ice zombies will be vanquished.

There is no comparable struggle for the future of Gormenghast Castle. The battle for the heart of Gormenghast is over. Apathy and decadence won, ages and ages ago. Peake’s interest in the future of Gormenghast extends only as far as Titus, the reluctant heir, and his desire to escape. But before Titus is allowed to leave, he must defend the broken system from which he so desperately longs to escape.

No elves come to save Gormenghast in its darkest hour, no desperate alliances are formed. It isn’t a place where shiny swords get forged to fight evil. It is a place where cowards sharpen kitchen knives in the dark, and the heroes are oblivious until the last moment. Titus is only moved to fight against Steerpike’s evil when it presents a credible threat to his social status. And in the end, the person who hates Gormenghast the most must restore it to order and strength—an unflinchingly cruel narrative choice, with such potential for excellent drama.

Gormenghast’s magic is ultimately only as potent as the imagination of its fans. If a new adaptation succeeds it will do so by staying faithful to its bleak outlook, florid language and bizarre mise-en-scene. We might soon be ready for Peake’s unapologetic weirdness. For now, though, Gormenghast castle is still obscure, unknown by a world determined to ignore it.

Ethan Davison is a graduate of Columbia University’s fiction MFA. Recently he wrote about the critic Martin Seymour-Smith at The Millions. You can follow him on Twitter @eadavison.