Welcome to Close Reads! Leah Schnelbach and guest authors will dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, Leah Blaine pulls her well-worn Sunfire Romances down from the shelf to look at the importance of an innocuous book cover.

As a young reader, I had the typical rotation of books befitting a young girl from the suburbs: Baby-Sitters Club, Sweet Valley High, and various romance books. These books reaffirmed my own life and looked like mine did: girls in school grappling with friendships and crushes, parents and homework, expectations to work for good grades, to be well-mannered, and to someday grow up to be a mother and perhaps a teacher/nurse/secretary. One series, however, blew my world wide open and the books looked even more innocuous than those prototypical books churned out for voracious 1980s book girls.

Covers as cover, indeed.

Sunfire Romance books were written by a collection of writers under pen names that all followed the exact same formula: a teen girl from a specific historical era with dreams of her own must choose from two very different suitors. There are glaring offenses in the book that cannot be ignored (unsurprisingly, a la American Dolls, Corey, the black heroine of her book, has escaped from slavery). And yet, in a time and place where racial, social, and economic boundaries were strictly drawn, as they were in my time and place under the Cold War and Reagan, the fact that historical characters ventured to friendships and even romances with people different than them was revolutionary to a girl in a safe box made of ticky tacky.

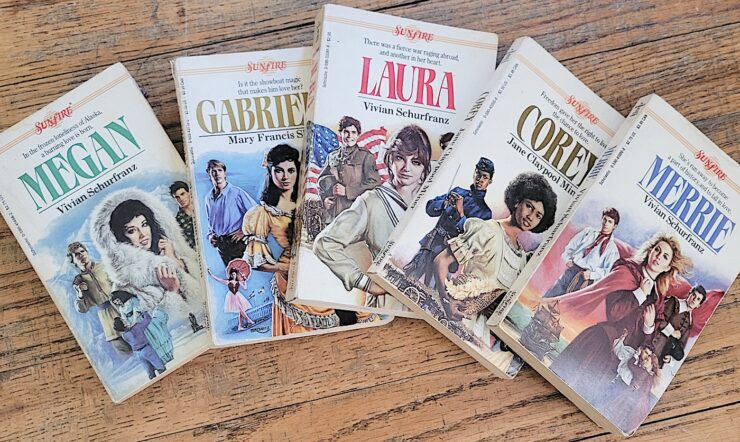

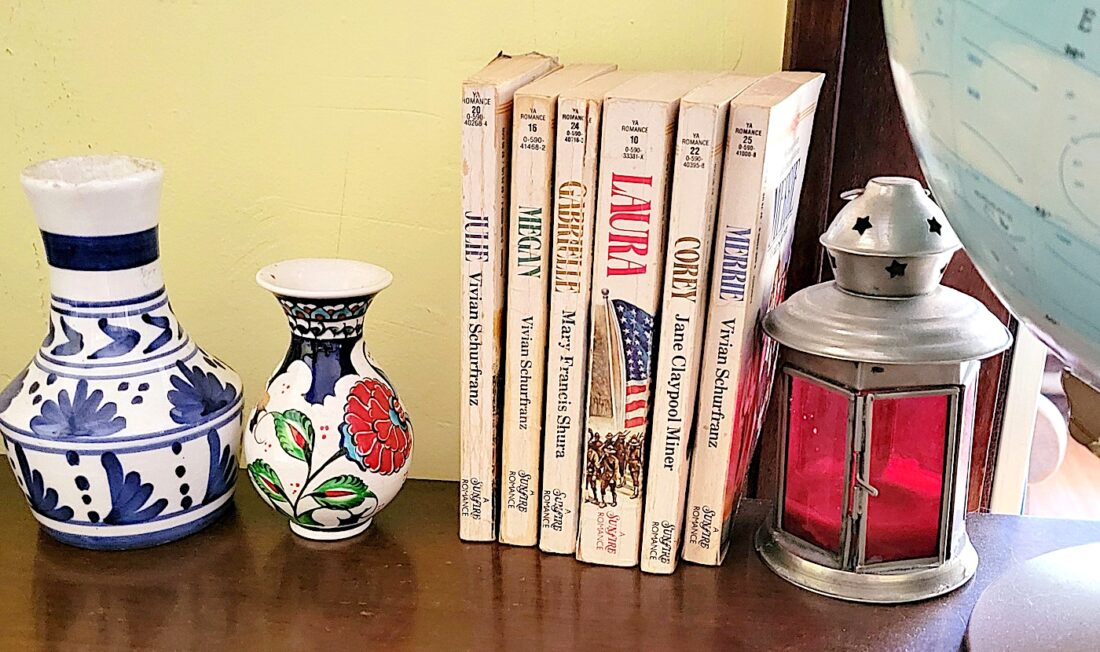

From the covers alone, these are books that should have merely fanned the romantic passions of teen girls. A young woman stood at the center with her name, always the title, emblazoned above her while a male suitor stood at each shoulder (there would be a third suitor in the foreground for some lucky heroines). They would be dressed in easily identifiable historical clothing with a scene from the book depicted, like a kiss in front of a stagecoach or forlornly leaning on the rail of the Mayflower. There is nothing from the covers that hinted at the absolute agents of chaos living in the pages.

Because this is where the formula ends. Each heroine had her own dreams and desires. Some wanted to enter the accepted vocations of women of their era; plenty wanted to be teachers and nurses and many wanted to marry and have children. Others, however, wanted to work in the circus, be a war spy, or become a journalist. One young woman, Caroline, cut her hair, dressed as a man, and went by Caro (a family name, she said) in order to make her way to California for the Gold Rush like her brothers. Another, Renee, wanted to be a reporter in New York so badly she braved the Great Blizzard of 1888 to earn her first byline.

Their choices for romantic partners were typically confined to a hometown boy and one new to town–and, again, this is where the formula ended. The hometown boy didn’t always expect her to settle down and raise a family; sometimes they wanted to travel, leave the dust of their town behind them. The mysterious (because of course he was) stranger wasn’t always interested in blowing in and out with the wind, taking her along with him to exciting and different locales; sometimes he wanted to settle and confine her to where he thought she belonged.

The dreams of the heroines and their romantic partners’ ideals would also collide just as much as they would match. There was no formula for their alchemy and each heroine had to grapple with how to have her romance (the point of the books after all), but also stay true to who she wanted to be beyond the romance. Renee found fulfillment and success with her new career only to have her boyfriend expect her to leave it all behind to marry him and start a family. Caro, at least, got to keep her hair short and wear pants when her love proposed a life together; he loved her as she wanted to be, not his version of her.

And this is why books are banned. Not because they teach children how to rebel, teenagers know full well how to rebel, but because they show that the choices laid out by their family and community aren’t choices at all, but rather acceptable options already chosen for them. The idea that children would dare to choose something not offered to them is downright offensive to many parents and must be avoided at all costs hence micromanaging even the fiction they may come across.

This is what makes the Sunfire Romances so revolutionary for their time. Because if parents knew what these romance books were doing to their girls, the girls they wanted to grow up to organize bake sales and preside over the PTA (because obviously they would only be wives and mothers) then these books would be at the top of the banned list. They were an instruction manual on how to choose your own path. Taken alone, they were harmless stories of finding a husband. Taken together, they’re a road map to finding a life free of restrictive expectations. Rife with feminism under the corsets and petticoats, each girl was able to choose the elements to keep and the ones to leave behind. Some chose traditional paths and some did not, but every time, the thought and care that went into choosing for herself was evident. They weren’t merely rebelling against expectations for rebellion’s sake, not that there’s anything wrong with that if you ask me, but considering how the expectations of others and their own desires shaped their choices so as to be true to themselves.

Never was this more evident than in how we talked about these books that we devoured so quickly. For romance books, we spent very little time talking about the romance. No, we talked about how we looked up the Johnston flood after reading about Jennie (who knew Morse code and we needed to learn that, too; I can still tap out “hi” because of her) or about women’s suffrage thanks to Laura (whose mother told her to stop worrying about her rights because she needed to marry and marry fast). It’s unsurprising how many of those friends went on to be excellent researchers as this was pre-whole world in our palm days; we could use a card catalog and navigate a library with our eyes closed by the time we left high school because looking up “how many women spies were there during the American Revolution?” (thanks for your service, Sabrina) or “what were conditions like in textile mills?” (good job joining the strike, Joanna) took up most afternoons and were never evident from the covers. We talked about not only the historical events, but how young the heroines were–that was something slightly mind-blowing to girls who had to be home when the street lights flickered. Margaret left Chicago for Nebraska by herself at 15 to teach in a one room schoolhouse while Merrie stowed away on the Mayflower. Again, line the books up together and it makes for a pretty impressive list of rabble-rousing young women who also liked to be twirled about and kissed and given flowers.

There is a direct line, then, from these covers to the Bridgerton screen adaptations and what romance readers have known for years: a cover that extols the virtues of a hetero romance may just be the undoing of women’s roles and expectations.

And thank every heaving bosom for that.