In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

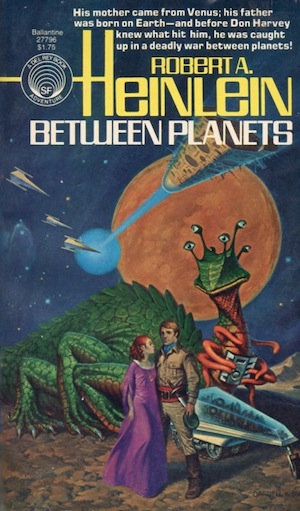

Every Heinlein juvenile is different, but Between Planets stands out from the crowd. The setting is a revolutionary war between Terra and its colonies, Venus and Mars. The hero, Don Harvey, must survive murderous secret police, space battles, invasions, jungle warfare, and even more space battles. All of Heinlein’s juvenile protagonists face jeopardy, but Don sees more than his share. The result is a book that transcends the juvenile category, a coming-of-age story that appeals to readers of all ages.

Between Planets was published as a Scribner’s juvenile in 1951, and has the distinction of being serialized twice. The first was in Blue Book magazine just before the hardcover publication, while the second was a somewhat modified version in comic strip format that appeared in Boy’s Life magazine in 1978.

I’m not sure when I first encountered Between Planets. I believe it was one of the juveniles I missed in my youth, and my first exposure was when I listened to an audio drama version from Bruce Coville and the Full Cast Audio group (they’ve done audio versions of many Heinlein juveniles, and if you can find them, they are worth a listen). I wanted to have a physical copy to consult for this review series, so I purchased a used Science Fiction Book Club omnibus, To the Stars, which includes Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, and The Star Beast.

During research for this review, I stumbled across an introduction to a Baen reprint of this book, written by Heinlein biographer William H. Patterson, Jr., which touches on Heinlein’s thoughts regarding the juvenile series in general, and this book in particular (you can read it here). It offers some interesting background on the editorial pressure that kept Heinlein from portraying anything more than a hint of romance in his juveniles.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) was one of America’s most widely known science fiction authors, frequently referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Glory Road. From 1947 to 1958, he also wrote a series of a dozen juvenile novels for Charles Scribner’s Sons, at a time when the firm was interested in publishing science fiction novels targeted at younger readers, particularly boys. These novels include a wide variety of tales, and contain some of Heinlein’s best work (the books I’ve already reviewed in this column are underlined, with links to the review): Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Spacesuit Will Travel.

The Fascist Federation

While there are similarities to the worlds portrayed in each Heinlein juvenile, each of them stands on their own. One thing the worlds generally have in common, though, is that they are dangerous places for their protagonists. And the world of Between Planets ranks among the most dangerous of these settings: ruled by the Terran Federation, a fascist state that controls not only the world, but the entire inhabited solar system. If there was a Space Patrol in this world, as Heinlein portrayed in previous juveniles, they seem to have failed in their mission, because the planet appears to exist in the aftermath of an atomic war.

Buy the Book

Emergent Properties

The police in the Federation operate with impunity. They follow and surveil whoever they want, arrest who they want, and appear indifferent when someone dies in custody. There are no traces of safeguards like probable cause, search warrants, or Miranda warnings in their procedures. One of the main venues in the story is New Chicago. While there is no mention of what happened to old Chicago, a large portion (if not all of) the new city is burrowed deep into rock, and there are active air raid procedures in place, implying that old Chicago did not have a happy ending.

The Federation has a giant space station in orbit, Circum-Terra Station, which in addition to being a way station for travel between planets, is also the repository for large numbers of atomic bombs, and even fusion bombs. These weapons keep restive nations in check around the world. The Federation also attempts to impose itself on its colony worlds, and seems indifferent to the wishes of the indigenous races of those worlds. While Mars and Venus are habitable, as they are in the other Heinlein books, the races that inhabit them are different in Between Planets. The Venusian otter people of Space Cadet are replaced with giant intelligent dragons, while the tall and mysterious Martians of Red Planet are replaced in this story by smaller people with vestigial wings, who have trouble in the heavier gravity and thick atmospheres of Terra and Venus.

The political situation shares some similarities with that of the English Colonies of the American Revolutionary War. This is not a new theme for Heinlein, as he used it in books like Red Planet and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, but here the parallels are more obvious. The biggest difference between this book and the other juveniles comes at the end of the novel, as the rebels develop super-weapons that completely change the balance of power and have the capacity to transform human society. It is the kind of development that is hard to fit into any future history, because it changes the game completely. The fact that Between Planets is not part of a future history, however, gives Heinlein a chance to fully explore these interesting ideas.

Between Planets

Don Harvey is a student at an all-male boarding school/dude ranch in New Mexico, a type of school that was once relatively common, but now reads as an anachronism. He is three months from graduation, after which he will join his Earth-born father and Venus-born mother on Mars, where they work at a research station (Don himself was born on a spaceship between planets, hence the title of the book). He is out riding his horse when he receives a call on the phone built into his saddle (Heinlein foresaw cell phones—rare among writers in those days). The headmaster asks him to return immediately, because his parents want him to leave for Mars on the next possible rocket. The headmaster assumes this is because of increasing tensions between the Federation and the colony worlds.

Don flies to New Chicago, and at the airport meets a native from Venus, where he’d spent most of his youth. The dragon-like creature uses the name of Sir Isaac Newton when speaking to Terrans, and the two exchange pleasantries in the whistling speech of Venus. Sir Isaac Newton is a delightful character, eccentric and charming from his first appearance. Don’s parents urge him to visit his “uncle,” a Doctor Dudley Jefferson, before leaving. The doctor takes him to a restaurant that features scantily clad female dancers (I’m not sure how Heinlein thought that detail was appropriate for a juvenile). The doctor asks if Don received the package he’d sent to the school, Don says he hasn’t, and the doctor insists that he cannot leave on his journey without it. At the doctor’s apartment, security police are waiting; after searching the place and interrogating both of them, the police coldly inform Don that the doctor is dead of a sudden heart attack. Don is disturbed, and heads back to his room, where the package from the doctor has arrived, forwarded from school. It contains a cheap plastic signet ring, and Don puts it on, wondering what all the fuss was about.

In the morning Don arrives at the spaceport and encounters more bureaucratic interference and police questioning. It is not easy for someone like him, without a home world, to travel. He sees Sir Isaac Newton, volunteers to share a compartment with him, and helps with treatment when the dragon has medical difficulties. When they arrive at Circum-Terra Station, they find it in the hands of the “Venus Republic High Guard,” a newly minted military group. No flights will be leaving for Mars, and they want to send Don back to Earth. But if he can’t go to Mars, Don would prefer to go to Venus. Sir Isaac Newton (a member of Venusian royalty, as it turns out) repays Don’s kindness by vouching for him, and insisting they allow him to go to Venus (one of those little object lessons about good deeds that Heinlein likes to slip into his juveniles).

The High Guard load the civilians into ships bound for Earth, set off a nuclear weapon to show what they could have done, and then blow up the station itself. The paranoid Federation destroys the ships loaded with civilians, fearing they are part of an attack, and blames the slaughter on the High Guard. A sergeant explains to Don that without its cache of orbiting nuclear weapons, the tyrannical Federation will be too tied up with revolts and international clashes on Earth to be able to move against Venus.

When he arrives on Venus, Don goes to the local IT&T office to send a message to his parents, but discovers his Federation money is worthless (he does meet a pretty young woman named Isobel Costello along the way, so his errand is not a total loss). He gets a dishwashing job with room and board from a man named Charlie who runs a Chinese restaurant (there is a labor shortage caused by young men joining the military). Someone breaks in and attempts to rob him—he suspects they are after the mysterious ring he has been carrying, so he goes to Isobel, and asks her to store it in her office safe. She agrees, and the two begin a friendship (in the very chaste manner of juveniles in that era).

Then the Federation attacks (so much for the plan to tie them up with problems on Earth). Charlie is murdered by an attacking soldier, and Don ends up in a prison camp. He escapes, and Heinlein gives us the harrowing account of his desperate flight across the trackless swamps of Venus. Don joins the military for a long stretch, and while the book doesn’t give details, it implies he has killed men in a number of ways, including up close and personal with his knife. Eventually, Don is finally reunited with Sir Isaac Newton, who (it turns out) is associated with scientists who are resisting the Federation—including Don’s parents. It transpires that Isobel and her father from the IT&T office are also members of the resistance. Everyone asks Don where the ring is, and when he admits having given it to Isobel, she fishes it out of her clothing. The resistance had the ring for months, and didn’t know it…

We learn that the ring has all sorts of secret scientific information embedded in it in a kind of nano-text, and soon there is a crash project to develop weapons that will transform human society to a degree beyond even the development of nuclear weapons. I will leave the rest of the story aside, so as not to spoil any surprises about the ending of the novel.

Final Thoughts

Between Planets is one of the most engaging of Heinlein’s juveniles, a feat accomplished largely by keeping poor Don in constant jeopardy from beginning to end, which forces him to grow up rather quickly. He is a target of murderous secret police operatives, caught first in the invasion of a space station and then of the Venus colony, is lost in the swamps of Venus, serves as a revolutionary guerilla, and then ends up right in the middle of even more space battles. If you want action, adventure, and humor in your coming-of-age stories, then this is definitely the novel for you. I should note that I especially enjoyed the side characters, with Sir Isaac Newton an eccentric delight, and Isobel a self-confident young woman who never needs rescuing. And now I look forward to hearing from you, whether it is regarding Between Planets in specific, or Heinlein’s juvenile series in general.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.