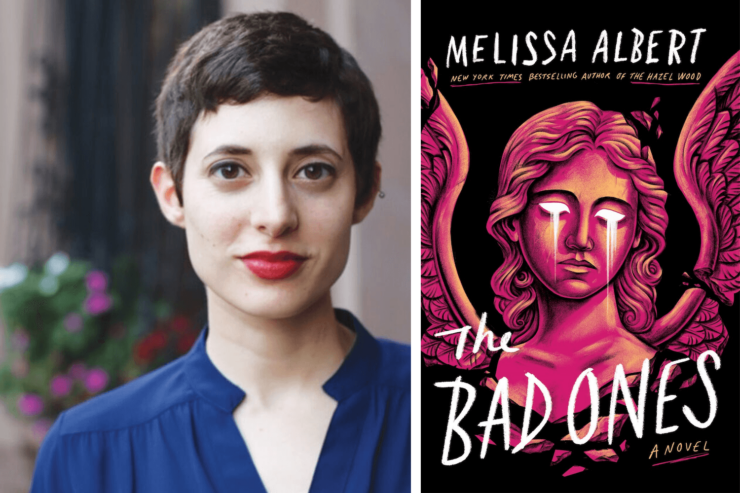

Melissa Albert writes young adult books that don’t necessarily feel like YA—that is, there’s an accessibility to this 35-year-old reader, especially since they depict both fully fleshed-out teens and adults (more and more of the latter’s perspective with each book); yet they don’t fall into the common genre trap of wholly catering to adult readers, either. The characters are age appropriate, but the forces with which they grapple—ranging from fairy tales come to life, to fraught friend breakups—demand that they change and mature in ways that reflect the universal coming-of-age experience. Just, you know, through the filter of dark fantasy or even, with her latest novel The Bad Ones, outright horror that is nevertheless hopeful.

Crucial to this success is Albert’s assuredness writing in mash-up subgenres that just make sense, like how she describes her debut novel The Hazel Wood as “fairy tale noir.” She arrived at the term somewhat by accident, by noting her own influences of Raymond Chandler and Angela Carter melding into her protagonist Alice Proserpine’s distinctive voice that made her ask herself, “Why would a teenager be so hardboiled?” This is the keen focus that Albert brings to every conversation, whether catching up over Mexican food or interrogating her own writing process. Perhaps it’s the journalist in her, but there’s also an innate warmth and attention to detail; she authentically wants to know every answer, no matter how trivial or important. In this case, the explanation was that Alice grows up outrunning bad luck that it turns out is part of her bloodline, as indelible as ink on the pages of the dark fairy tale collection that tells her who she really is.

Like Alice, who learns about herself through reading Tales From the Hinterland, Albert’s path to bestselling author began by writing other people’s stories. Despite her initial post-grad job path focusing more on journalism and theater reporting in Chicago, when Albert moved to New York City in late 2010, she took on work-for-hire writing gigs developing YA plots in the post-Hunger Games era. This eventually led to expanding said plots into pseudonymous novels, which she describes as “like getting paid to learn how to write, like a craft class.”

As the founding editor of Barnes & Noble’s much-missed Teen Blog, Albert found herself strengthened as a writer because it allowed her to be not a gatekeeper but a “celebrant” of books. (Full disclosure: I met Albert as a contributor at B&N Teen, and we have since become neighbors and friends.) As she explains, “I saw this amazing Amal El-Mohtar quote the other day where she referred to being a critic as trying to make herself the perfect reader for every book—and that was the B&N job. Every book I read, it wasn’t my job to say, ‘This isn’t good enough, read this other thing.’ It was, ‘Oh my god, who’s gonna love this?’ Like constantly mentally matchmaking.”

While playing matchmaker, Albert was also drafting The Hazel Wood. Then during the time between selling her book and its publication, she underwent another transformation—into a mother. The Hazel Wood was published in early 2018, just a few months after the birth of her son Miles. Her New York City book launch was at the Barnes & Noble Tribeca store, in conversation with Holly Black, Albert beaming with what she accurately describes as “the hollow zombie sparkle” of early parenthood sleep deprivation. With her bright-eyed enthusiasm and penchant for droll self-deprecation, Albert is an unflaggingly engaging storyteller. She reenacts how “intimidated” she was to meet Black before the event, not least because it was the first time she and her husband had hired a babysitter: “Right before I meet her I’m like, ‘I’m gonna check my app and see my baby,’ and there’s no volume but he’s in bed going [mimes screaming and flailing] and I close it and put it away like, ‘Hi, Holly Black, nice to meet you.’”

Like many writer moms, Albert balanced her various obligations as well as she could: baby Miles tagged along on her book tour; she had her day job at B&N and worked on the second novel she’d sold in the evenings after putting him to bed. But it took a two-month sabbatical, with the freedom to write in the daytime instead of in exhausted 90-minute chunks, to accept that she needed to focus solely on her own writing or else “I would be putting a book out that I was sad about because I wasn’t giving my whole self to it.”

She had “one idyllic year,” and then the pandemic hit—which meant juggling Miles’ remote learning from home while also fulfilling her book contracts. By the time she was working on her standalone novel Our Crooked Hearts, and Miles and his peers were back in school, she had figured out what works. Albert wryly jokes that she is “a totally square, 9-to-5 artist; I actually have to keep office hours.” She thrives on the routine of writing while Miles is at school, using pickup as that clear divide in her day. Evenings and weekends are for family time, barring the occasional deadline; “when he’s in my house and my presence, I never ever try to work,” she says. Watching her bright, inquisitive son pick up on the details of her job is an additional delight, especially when he tries his hand at writing his own stories. Though Albert was initially bemused when he presented her with “his” story—copying down “Jack and the Beanstalk”—she quickly appreciated it in the context of retelling a fairy tale: “Just seeing how when I tell him that story, what’s meant a lot to him, throwaway details he’s painstakingly writing down.”

The big life change of motherhood—and its many attendant micro-transformations—forced Albert to reevaluate the character of Alice’s mother Ella when writing the Hazel Wood sequel The Night Country. She’ll be the first to acknowledge that Ella’s disappearance in the first book “is a bit of a MacGuffin” in that it gives Alice something to chase, without actually being the point of the book. “And that’s because I wasn’t a parent then, so I only thought as a daughter,” she says. “[Alice’s] story is defined by her mother’s presence or absence, but I don’t actually know what the mother’s like, really.” It was only in writing the sequel that she “cared” enough to get to know Ella better.

Albert established the mother/daughter dynamic in a much more deliberate manner in 2022’s Our Crooked Hearts, which she calls “the most lovely writing experience of my life.” The fondness in her eyes and voice is palpable. “It was an escape from the pandemic; it’s just everything I love.” Albert drew upon her upbringing in the northwest suburbs of Chicago, plus what was becoming her signature style of dark lore, to develop what she calls “suburban fantasy”—building on some of the familiar language and tropes of urban fantasy, but rooted in the very liminal space that so many adolescents inhabit: “We know why the city is scary; we know why small towns in the middle of nowhere is scary; so my question was, why are the suburbs scary?” If you’re delivering pizza in unincorporated towns like a teenage Albert did, that might mean one heart-stopping night when a deer rushed past her car while she stopped to read handwritten directions for her order. The memory stuck with her—“the suburban road, trees rushing past, all bleached out by your headlights”—except in the opening of Our Crooked Hearts it’s not a deer, but a naked woman eerily out of place in the middle of the road.

The book occupies dual timelines, shifting between seventeen-year-old Ivy in present-day suburbia, and her unapproachable mother Dana’s own coming-of-age in 1990s Chicago with her teenage coven. These timelines intersect in a ghost story that’s chilling for the “unforgivable” acts that Dana commits, certainly as a teenager but especially as a mother—the ultimate invasion of her daughter’s privacy and autonomy, but presented in the achingly relatable context of, as Albert puts it, “the ‘am I doing this right?’ mom thought.”

Despite The Bad Ones not following the dual-timeline style, it’s where the presence of motherhood most crystallizes, in the authentically lived-in dynamic between protagonist Nora and her mother Laura. The heart of the novel may be rooted in the best friend breakup between Nora and Becca, with Becca’s mysterious disappearance spurring Nora into reexamining their childhood games turned into deadly rites of possession, but the inciting incident is communicated between mother and daughter. It’s Laura who calls Nora home from a desperate attempt to reconcile with Becca to tell her that three other people in the community have also vanished under similar circumstances; and when Nora’s search through Becca’s trail of clues causes her to act increasingly erratically, her mother calls her on her bullshit in a way you might not always see in the genre. “It’s easier to have the parents not notice what’s going on,” Albert says, “so I wanted to write a scene where I made it less easy on myself. I didn’t want the heroine sneaking up to her room every time; at some point her mom’s spidey senses are going off, because of course they are.” Complicating this fact is Nora’s history of lying; not that she comes into the story as an unreliable narrator, per se, but her childhood penchant for fabrication colors just how much adults will trust her to tell the truth, especially when the only explanation for the disappearances is supernatural.

Most of all, Nora learns from her mother not to be afraid of being vulnerable in front of each other. Laura’s experience of chronic pain is an everyday aspect of their family life—a personal touch that it was vital to Albert to include. “When I was pregnant, I was worried my child would be mad at me for my weakness, in having chronic pain,” she says. “And a friend of mine told me, ‘No, your child is raised by the parent they have. It’s gonna shape them; they’re gonna accept the table stakes, what you can and can’t do,’ and they were totally right. So I’m not done writing chronic pain in books, but this was my first foray.” Table stakes being a poker term meaning the least you can bring to the table: “If you wanna be in this family, the least you gotta do is accept.”

Buy the Book

The Bad Ones

There’s another form of family in this book, with its own table stakes, and that’s the all-consuming friendship between Nora and Becca. What initially brings them together is Becca’s artist’s eye, that provides them both with a lens on the world, but as it becomes clear that Nora doesn’t possess that same “unflickering flame of talent, ability, drive,” it creates a wedge between them. shot through with the tension of Becca being an artist while Nora is not. “She’s feeling her way through the world,” Albert explains. “She knows that she wants life to be bigger and better, and she wants to be more interesting, but, like so many kids, does not know exactly how to get there. Turns, as so many do, to lying to make things more interesting, and then with her best friend they collaborate together and it inspires her to turn that lie into fiction. And I love that idea—fiction as an off-ramp, art as an off-ramp—’cause if you make your own world by lying and trying to trick people, everyone’s mad at you. If you make your own world by creating something intriguing and engaging—be it a photograph for Becca, or a story like Nora—people reward you for it.”

Many a reader will likely recognize their own childhood imaginations run wild in the girls’ creation of minor goddesses representing every urgent important thing in girlhood, from the goddess of impossible chance to the goddess of revenge, avenging Becca’s mother’s death by a drunk driver. While Albert didn’t have her own adolescent goddesses to draw upon, she fondly recalls roleplaying with her friends as different Sandman characters writing a literary magazine. She put the power of taking on those personas into Becca and Nora’s games, where they don’t just create the goddesses but actually embody them in photographs: “that idea of being powerful when you are powerless, when you reach the ends of what you can do.” Albert was “super shy” as a child, and while she had a best friend, it wasn’t until junior high that she found that tight-knit group, that coven that she’s explored in her fiction, bound by “the heady, intense feeling of group effort.” She was drawn to witchy narratives of power, and especially “the idea of female community and the power you can have within that.”

But as grief and loss molds Nora and Becca into different people, and as older kids literally intrude upon their private make-believe, this act of creation transforms into a much more demanding and deadlier ritual. The goddess slips out of their control and becomes interwoven with the disappearances within their community… or, as Nora learns in her investigations, the goddess may have always been bigger than the bounds of their imaginations.

The Bad Ones weaves so many stories that intersect or layer over one another. There’s an intergenerational commentary on the true crime genre and (sub)urban legends, as Nora’s peers initially try to center themselves within the narratives of the missing classmates they don’t even know. Yet it becomes clear that it’s not just a case of “kids these days” dehumanizing the victims of true crime, it’s a cyclical horror that established its own strange cult following in their community. (Albert laughs as she relates what she’s often said to her husband: “I would absolutely have been ripe to have been picked up by a cult leader. I totally get how young, unformed people can fall down like that on that pathway. That powerful, seductive lure, then you add magic to it, and I just love to think and write and read in those spaces.”)

But what’s most striking about The Bad Ones is how the supernatural elements get to the non-magical heart of the teenage experience. Without giving too much away, the title taps into the sense of being a teen who can tell that you will have a life beyond high school—that you can tell who will peak, versus who will also make it out—yet you’re also so embarrassed to possess this mature foresight and not be obsessed with all of the psychodramas like your peers. It’s all right when you have a co-conspirator with whom to wrap yourself in this tiny club of exclusivity, but when that bond gets fractured, it’s incredibly lonely to be the only one who can see a life beyond this.

That’s the spiral that Nora inhabits, as she simultaneously feels abandoned by Becca immersing herself further into the cult of the goddess long after Nora gave up silly games, but also that she is not allowed to grow and change beyond Becca. Her best friend has lost both of her parents, but has been able to process that through her art; Albert describes Nora, by contrast, as “wobbling; she doesn’t actually know who she is because Becca has held her so tightly in Becca’s vision of what life should be.”

Albert taps so evocatively into this experience of how a teenager copes with being someone else’s entire world and figuring out how to show up for them after devastating loss, despite your brain not even being fully formed to know the ways in which to do that. “You’re too young for it,” Albert agrees gravely. “It’s more than you can give; resentment is bred. You’re afraid to change because it would be a betrayal of the person you were with them, and therefore them.”

In revising the novel, Albert realized she needed to not just play with the horror elements, but to surrender more fully to that genre. “There were things I wanted to do,” she explains, “and there were lines I did not want to cross—which I don’t want to say to spoil anything—and I had a strong idea of where I wanted to get to, but with the way I’d laid the table for myself, I was like, how am I gonna get there. And the answer was on the one hand to go a lot more toward horror than I anticipated, which was really exciting; and on the other side of it, there’s a certain hopefulness to the ending. It was important to me to maintain both.”

She points to Grady Hendrix as a big inspiration for this balance, especially his recent novel How to Sell a Haunted House. “He is so excellent at writing characters who are totally fucked-up, completely ridiculous in some ways,” she says. “Another author might paint them as a dreg, but in his hands there’s so much empathy. They’re people for themselves; their lives have value, you never doubt that. He writes women beautifully; he always writes female protagonists, and they’re always so richly done. He’s always so funny and so scary, and his combination of the high and the low—genre elements, but really workaday working-class people details, like things I recognize from my own life. Like, his haunted house is set in a shitty ranch house. I think about [his work] a lot, because he writes really pop culturally-saturated things, but even when it should be campy in its shape, it’s too full of empathy to be campy.”

It may come as no surprise that Albert’s next project is (she hopes) her adult debut, albeit with the same blend of contemporary setting and fantastical elements. And while she’s keeping most of the details close to her chest, the way she describes it has that dreamy feel of magical games in the woods where no one else can eavesdrop or judge: “It’s playing with so many of the things I’ve been interested in all along: So I’m really interested in women artists, the act of creation; I’m interested in the specific way people look at women who create and the compromises people make to be artists. I’m really interested in invented culture—books as, like, objects and business and a cult object. I’m interested in fandoms and how people engage with things they love, cultural things. And at the heart of it is a sibling relationship, which I’ve never really done before. I’m excited.”

The Bad Ones is published by Flatiron Books.