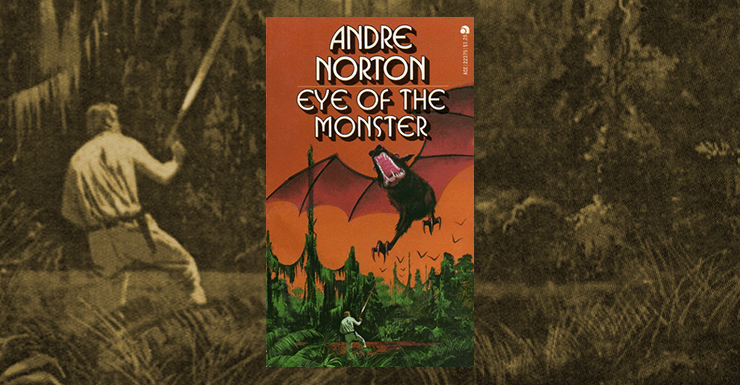

Eye of the Monster is an interesting book in multiple senses of the phrase. It’s the story of a standard plucky Norton hero, this time named Rees Naper, struggling to survive on a hostile planet, in this case the colony planet Ishkur. Rees is the son of a Survey man, and his mother, as usual in these novels, is dead.

Rees’ father has disappeared and Rees has been forcibly adopted by his uncle, pulled out of Survey school and hauled off to Ishkur to be instructed, or rather indoctrinated, in his uncle’s “mission” beliefs. Uncle Milo is a true believer, and that belief is sharply at odds with the reality of the planet.

The Empire to which Rees refers here appears to be Terran, which is a bit disconcerting after the alien empire of The Sioux Spaceman. It’s been colonizing worlds occupied by sentient but low-tech native species: here, the reptilian Ishkurians whom Rees calls Crocs—and that, according to young Gordy, Rees’ very reluctant companion, is a “degrade name.” Or, as an older person might say, a pejorative.

The Ishkurians, like the native people in The Sioux Spaceman, are divided between free tribes and more or less indentured servants of the offworlders. When the novel begins, the planet has hit flashpoint. The Patrol has pulled out, and there have been native uprisings in multiple colonial settlements. The colonists are withdrawing. Even the missionaries are starting to think they might need to retreat, except for Dr. Naper, who is serenely and obliviously convinced that everything is just fine.

Of course it isn’t, and Rees barely escapes alive with Gordy and an equally young Salariki child—one of a species of feline aliens whom we first met in the second Solar Queen book, Plague Ship. His uncle is bloodily massacred along with the rest of the mission. Rees commandeers an odd vehicle called a jungle roller or simply roller, a sort of ATV/tank with the ability to make short aerial “hops” across difficult terrain.

Buy the Book

All Systems Red: The Murderbot Diaries

They take off in the roller with the Ishkurians in pursuit, pick up an adult Salariki female who is more than capable of holding up her end of the expedition, and do their best to get to the nearest fortified holding. When they finally make it after harrowing adventures, they find it deserted. And then the natives attack—but Rees is able to trigger a call for help, and they’re rescued just in time.

I was forewarned about this one. Strong female character, check. Alien female, naturally; this is 1962, we won’t get many functional (or even living) human female characters for another few years of Norton novels.

Major problematical issues, yowch. Check. Rees is all about the Survey and the exploring and the colonizing and the degrade-words about nassssty murdering reptiles. The bleeding-heart-liberal views of his uncle are presented as repellently smug and smarmy, and Uncle Milo ends up very dead.

And yet.

I wonder just how reliable a narrator Rees is. It’s not like Norton, even in this period, to be so overtly racist. She tries hard to cultivate what we now call diversity, and her monsters are usually so totally alien that there’s no point of contact with them except run-fight-kill. Nor is it like her to be so strongly anti-not-us.

Uncle Milo isn’t really a liberal. He’s much more like a pre-US-Civil-War Southerner going on about the happy slaves, so grateful for the civilizing influence of their white masters. British colonialists in India during the Raj said much the same—and died for it, too.

Rees on the one hand calls the Ishkurians by a racist pejorative, but on the other, tries to get into their heads. Admittedly he thinks of them as evil creatures whose mindset he can barely stand to replicate, and he does it in order to defeat them. Nor is he making the slightest effort to understand why they’re rising up against the colonizers. Still, the fact that he does it at all is very interesting.

At the same time, he’s bonding with another species of alien, the Salariki, who are much more attractive and much more comprehensible. They’re also not trying to slaughter him. And, they’re mammals. He feels much more connection with them than with the reptiles.

I wonder if Norton is trying to be subversive, if she’s saying that colonialism is not a good thing even when Terrans do it. Especially considering that in so many of her series at this time, worlds occupied by sentient species are off limits to colonization—most notably in the Janus books—and in The Sioux Spaceman she gives us almost the same plot but turned inside out: The Empire there is evil, and the protagonist fights on the side of the natives.

Reading these two books side by side, I’m not sure we’re supposed to be entirely in Rees’ camp. He’s pulled up short more than once, and there’s much discussion of the deep philosophical disagreement between Survey and the missions. (And then there’s the trader side of it, as represented by the Salariki, which is a lot more neutral.)

There’s a particularly interesting passage about a third of the way in:

He could not subscribe to Uncle Milo’s abhorrence of Survey’s basic tenets. Just as he could not and would not agree that Survey’s opening of new planets only tended to increase the colonial rule of the Empire and perpetuate what Dr. Naper and those of his association considered the most pernicious aspect of Terran galactic expansion.

Obviously Rees is on the side of colonialism, but he’s landed on a world that has blown up into a violent native revolt against it. He survives, but only through cooperation with an alien (and a female). The Ishkurians have fought for and won their independence; the Terrans are in the process of being driven out. He’s all starry-eyed about the future at the very end, but that future isn’t on this planet. Uncle Milo was basically right.

I think Rees is going to learn this lesson as he goes on. The Salariki points out, gently, that there’s more than one way to explore the stars. One can be a Free Trader, for example.

Free Traders, be it noted, don’t colonize. They explore, they trade. They don’t force their views on anyone—in fact they’re notoriously clannish and closed to outsiders.

I think Norton may be speaking through Isiga, telling Rees something he needs to know. And telling us that we’re not to trust his viewpoint. Her intention is more complex; she wants us to think about all the different sides of the question.

I’m off to Voorloper next. That should be interesting: It was published much later than the rest of the series, in 1980, and our world, and the genre, had changed profoundly.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.