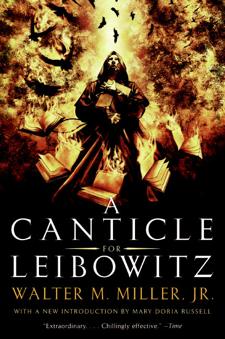

So after re-reading 1959’s Hugo winner A Case of Conscience (post), I couldn’t resist picking up 1961’s Hugo winner A Canticle For Leibowitz. It may not be the only other explicitly religious Hugo winner, but it’s certainly an interesting contrast.

A Canticle for Leibowitz is about a world that has been through a flood of fire—a nuclear war that has left survivors to grope through a new dark age. It’s set in the barbarous ruins of the U.S., and it’s explicitly reminiscent of the period after the fall of Rome when the Church kept learning alive. It’s a clearly cyclic history, with civilization rising and destroying itself again. You’d think this would be a terrible downer, but in fact it’s light and funny and clever as well as moving and effective and having a message. It treads some very strange ground—between fantasy and science fiction (the wandering Jew wanders through), between science and religion, between faith and reason, between humour and pathos. It’s an amazing book, covering a thousand years of future history, making me laugh and making me care. It’s hard to think of anything with the same kind of scope and scale.

Walter M. Miller was an absolutely wonderful short story writer. In short form he managed to produce a lot of poignant memorable clever science fiction. A Canticle For Leibowitz is a fixup of three shorter works, and he never wrote another novel. There’s a sequel of sorts, St. Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, which he worked at for years and which was finished for him by Terry Bisson. Despite loving Bisson I haven’t been able to bring myself to read it. For me, A Canticle for Leibowitz is complete and perfect and doesn’t need any supplementary material, sequels or prequels or inquels.

The three sections of A Canticle for Leibowitz were published in SF magazines in the late fifties, and then the novel came out in 1960, winning the 1961 Hugo award. The concerns about nuclear war, and the particular form of nuclear war, are very much of that time. This is a rain of fire that destroys civilization and leaves mutants but doesn’t destroy the planet—that waits for the end of the book and the final destruction. This is the survivable nuclear war of the fifties and sixties, the war of The Chrysalids and Farnham’s Freehold. But this isn’t a survivalist novel, or a mutant novel—although there are mutants. This is a novel about a monastery preserving science through a dark age. Almost all the characters are monks.

The central question is that of knowledge—both the knowledge the monks preserve, hiding the books, and then copying and recopying them without comprehension, and the question of what knowledge is and what it is for. There’s the irony that Leibowitz, the sainted founder of their order, was himself Jewish, which the reader knows but the monks do not. There’s the wandering Jew—and the question of whether he’s really the wandering Jew. When I think about the book I keep coming back to the illuminated blueprint, done in gold leaf with beautiful lettering and absolutely no idea what it is that it describes and decorates.

We see three time periods of the monastery of St. Leibowitz, and we can deduce a third, the foundation, from what we know and what they know. There’s a nuclear war, with awful consequences, followed by a hysterical turning on scientists, who are considered responsible, and on anyone educated—the “simpleton” movement. In response, Leibowitz and others became bookleggers and memorizers, using the church as a means of preserving science. The story starts several generations later, when simpleton is a polite form of address to a stranger, like “sport” to a mutant. The first section is about Brother Francis and the canonization of St. Leibowitz. The middle section is set at a time secular civilization is just beginning to get science organized, a new renaissance. And the third section is set just before the new apocalypse, with a few monks escaping to the stars and God’s new promise.

I want to repeat: it’s delightful to read. It’s easy to forget just how much sheer fun it is. I thoroughly enjoyed it—even the perspective of the buzzards and the hungry shark. It’s a surprisingly positive book.

The details of the monastery are pretty good. The Catholic Church was in the process of abandoning Latin at the time he was writing, and had renounced it entirely by the time the novel was published in book form, but he has them using it. (I have no problem with this. Of course, they’d have gone back to Latin in the event of a global catastrophe. I mean, it’s obvious. I’d do the same myself.) The preservation of science and knowledge generally is very well done. I love the scientist reading a fragment of RUR and deducing from it that humanity as he knew it was a created servant race of the original masters who destroyed themselves. There’s no dark age direct equivalent of bookleggers, but that doesn’t matter.

Spoilers:

Theologically though, looking at the fantasy aspects, I find it odd. To start with, there’s the wandering Jew, who appears in the first and second parts but not in the third. In the first part he leads Brother Francis to the hidden fallout chamber. In the second he’s known as Benjamin and claims to be Lazarus, explicitly waiting for the second coming. He doesn’t appear in the third part and there’s no reference to him—has he gone to the stars? If Rachel is the messiah, he misses her. And is she? I think we’re supposed to believe she is—and I like the weirdness of it, the science-fictionality. I don’t know that it’s orthodox Catholicism—and I gather from Wikipedia that Miller was a Catholic, and was involved in bombing Monte Cassino in WWII and then thought better of it. If this is true, he certainly made something to set against that destruction.

Teresa Nielsen Hayden says that if something contains spaceships, it’s SF, unless it contains the Holy Grail, which makes it fantasy. I don’t know whether the Wandering Jew (and potentially a new female mutant messiah) counts as the Holy Grail or not in this context. There are certainly spaceships, the monks are taking off in them as the new flood of fire falls at the end of the book. It doesn’t really matter whether it’s science fiction or fantasy or both. Hugo votes have never had much problem with mysticism, and they certainly noticed that this really is a brilliant book.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and eight novels, most recently Lifelode. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.