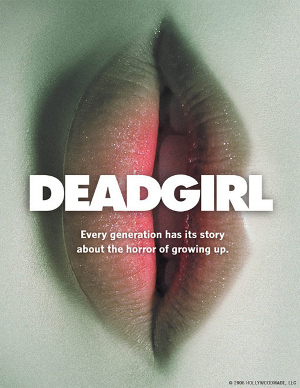

Horror, like pornography, often focuses on violations of the body. Which is why it is surprising that it has taken as long as it has for a movie like Deadgirl to make the intuitive leap and feature rape (without the comfortable distance of metaphor) as the central violation of a body in a horror film. Horror is also a reflection of our anxieties: about sex, about strangers, about terrorists (which explains the explosion of torture porn following 9/11). As the financial world crumbles and the poor get poorer, horror turns to examine power—the loss, the gain, and the transfer of it. Rape is just a different kind of struggle between the powerful and the powerless.

To its credit, Deadgirl understands that. With a sensitivity that belies its unfortunate but inevitable descriptor as “the zombie rape movie,” Deadgirl never once derails into titillation, for all that a naked woman is in almost every scene. Each violation of the Deadgirl is a grotesque. Sexual enthusiasm for the living dead “love slave” does not exist; the rapists are never aroused save where they must prove to one another that they are. Alone with the Deadigirl, they are pathetic losers begging for her attention (since they cannot secure hers or any other woman’s affection); in company, they posture and preen and measure their manhood.

In this way, Deadgirl offers more insight into the problems with and complications of modern male socialization than it focuses on interactions between the sexes. Two boys discover the zombie woman in a locked basement of an abandoned mental hospital, long forgotten by whoever made her that way. To J.T. (Noah Segal), she is an opportunity for him to grab power that he has never and will never have outside of her dank, dark cell. To Rickie (Shiloh Fernandez), she represents a challenge to his friendships with the only people he has left in his life, J.T. and Wheeler (Eric Podnar), another druggie nobody. (Rickie’s mother is a no-show; her alcoholic boyfriend exists only to spout hollow platitudes about manliness.) Caught between loyalty to his friends and disgust at their behavior, Rickie waffles indecisively for most of the movie.

Rickie’s inability to connect with other human beings sabotages any clear sympathies the audience has with him. He is, naturally, curious about the Deadgirl and tempted to use her to work out the sexual frustrations from his fruitless, unrequited attraction to Joann (Candice Accola), a temptation with which J.T. repeatedly baits him. While Rickie refrains from abusing the Deadgirl physically, his stalking of Joann and tolerance of J.T. and Wheeler’s abuses, as Co-Director Gadi Harel pointed out at a screening, hardly qualify him as a hero. Rickie’s fetishizing of Joann, which not infrequently makes her uncomfortable (when not outright frightening her), is merely a more socially acceptable form of the dominance game that J.T. is playing with the Deadgirl.

Joann and the Deadgirl form the core of an excuse for boys to mistreat and misunderstand each other. They are secondary ciphers that exist solely to provide a forum for dissecting male power dynamics. Joann’s jock boyfriend beats Rickie with fists and a baseball bat; Rickie takes his revenge by suggesting the jock accept a blow-job from the Deadgirl with the predictable result. Rickie considers himself better than his friends by dint of being a liberator—this despite the fact that, a, Joann does not want his help escaping a relationship of which she is willingly a part, and, b, he can not free the Deadgirl for fear of her attacking him. Either way, Rickie presumes as much control over the bodies of the women around him as J.T. even if he does not abuse them to quite the same extent.

That this was not immediately obvious to some viewers at the screening points to the failure of Deadgirl to emphasize strongly enough the parallels between Rickie and Joann and J.T. and the Deadgirl. As an excuse for Joann to tolerate Rickie’s antisocial obsession with her, the film offers a flimsy backstory wherein the two were childhood friends, with a twelve-year-old Joann being Rickie’s first experiment with romance. It gives their interactions a veneer of mutual interest whereas it is clearly one-sided, with Joann being forced to endure Rickie’s attentions to avoid making a scene (and thereby causing more problems between him and her boyfriend). While playing Rickie’s attraction to Joann as typical teenage awkwardness is a realistic choice, it disguises his control issues and makes some of his choices appear slightly out of character. Had Rickie never once spoken to Joann, his determined stalking would have explained his later behavior. Hard to believe that one can fault a zombie movie for being too subtle, but there it is.

It also bears noting that the exact mechanics of zombification are glossed over to serve the plot, typical of zombie films where discussing the means of transmission might derail the spook factor. Deadgirl, however, takes disinterest in the process to a new level, neither exploring the source of the Deadgirl’s immortality nor premising its scares on the possibility of her disease spreading to others. The focus is on the human monsters; thus, audience sympathy is with the Deadgirl. As great horror is wont to do, it allows the audience to accept and even revel in the carnage she creates.

Co-Director Gadi Harel objected to classifying Deadgirl as a horror movie, preferring to consider it a horrific movie. I disagree, if only because I believe that “horror” is not a pejorative term. (“Torture porn” is a pejorative term.) Horror implies that the film specifically aims to horrify, unsettle, and provoke a visceral emotional response. Aside from the horrific, those are qualities to which any film hopes to aspire. Without question, Deadgirl is a provocative film that manages to incorporate the horrific into an examination of humanity that is no less damning or unsettling than any belonging to “loftier” genres. It will preoccupy your thoughts long after the ending, and for that alone, it is well worth seeing.

Dayle McClintock took a class on horror movies once. There were no survivors.