He was a dark and tragic figure. In life he loved deeply and perhaps insanely. His was a love so profound that it dwelled in his still beating heart 3,000 years after fate had forsaken him and callously taken his lover away. Even in death the woman he idolized radiated an angelic beauty he could not resist. Once a man of the gods, a high priest charged with a sacred trust, he abandoned his calling, taken privileged knowledge and, defying his gods, he attempted to restore her to life. Some knew him as Im-Ho-Tep. Others called him Kharis, a prince rather than a priest. Perhaps they are one, or maybe they are two with a common calling, a mutual weakness and a similar fate. They (he) may have been mere movie monsters, the fabrication of a studio system more focused on quantity than quality, but when I was young they filled me with fear—and yet their quiet vigilance was, in an odd way, comforting. They lurked in the putrefying dankness of the forest, in the cool swamp, among the fallen leaves and the dead things and the thousand other terrors, not so dead, that creep and crawl and slither in the dark places where gentle, God-fearing folk never tread.

The real life Imhotep was, according to some sources, history’s first genius. A vizier and architect in the reign of King Djoser in the 27th century BC, Imhotep was reputed to have been the innovator of stone architecture, the engineer of the fabulous step-pyramid at Sakkara and a healer of mythic talents. Centuries after his death he was elevated by his people to the pantheon of rare human deities and today a statue of him, the most ancient physician whose name history remembers, stands in Chicago’s International College of Surgeons. The mythology surrounding this demi-god suggests that Imhotep was born of the union of Ptah and a human mother. Ptah was the god of creativity and said to have molded all the other gods and all the kings of Egypt from precious metals by first envisioning them, then speaking their names aloud. Such was Imhotep’s myth of exalted heritage and his chronicled reputation.

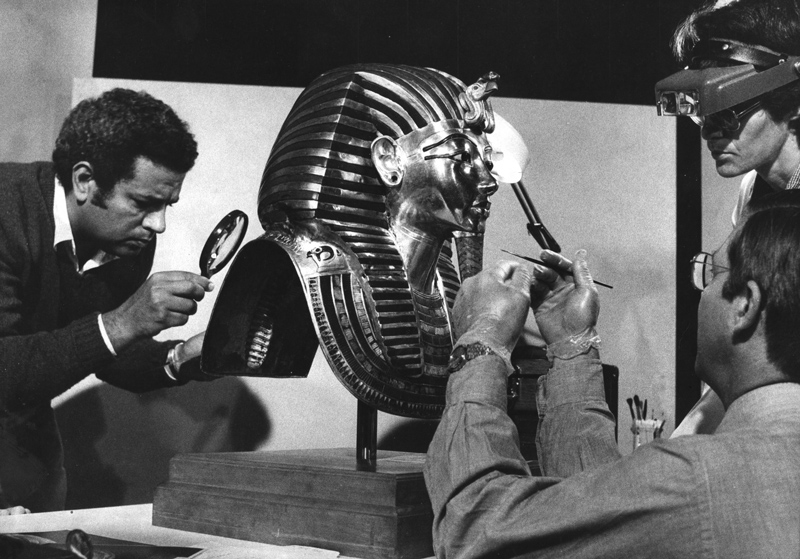

Popular interest in the ancient world that Imhotep inhabited reached its height in the opening decades of the 20th century as Britain’s occupation of Egypt reached its end. It is difficult to imagine, some ninety years after the fact, how much the discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in November of 1922 impacted the popular culture of the 1920s and ’30s. Tut was a boy of only eight or nine when he assumed the throne in 1366 BC, and was dead by the age of eighteen. His child bride was a daughter of King Akhenaton and it was through this union that Tutankhamen ascended to the throne. Of note to devotees of The Mummy on film is that the bride of the boy-king was named Ankhesenamen. Subsequent to Tut’s death, his young widow asked Shuppiluliuma, the king of the Hittites, to send one of his sons to Egypt so that they might marry and share the throne thus uniting their two peoples, but while en route to join her, he too experienced a premature death. From the perspective of cinema, Tut’s famous but baseless “curse” that anyone who defiled his tomb would die a violent death (apparently purely the product of tabloid sensationalism)—was a key inspiration for Universal’s 1932 horror masterpiece, The Mummy.

With the Tut find, the distinctive motifs of ancient Egyptian art and costume moved to the forefront of the Art Deco era. Art Deco appeared in architecture, product design and high fashion and incorporated many influences, particularly those of Egyptian, Roman, Greek, Japanese and Native American art and architecture, combining them with the streamlined geometry of the Machine Age. Art Deco reached its height in the interval between the world wars—roughly from about 1920 to 1939—although it began at the turn of the 20th century and endured until the mid-1950s. Ads in 1923 issues of The New York Times for Russek’s 5th Avenue Department Store, and in the April 15, 1923 Vogue, as well as other journals of style and fashion of the time, loudly proclaimed the influence of Tut and the new “Egyptian Look” in women’s clothing and footwear. Concurrently, the noted American illustrator C. Coles Phillips, the originator of the famous “Fade-away Girl,” produced art for at least two major ad campaigns, Palmolive Soap and the Fiberoid Company, depicting stylishly dressed women in Egyptian attire.

With the success of Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein (released respectively in February and November of 1931), the studio quickly established the reputation as the home of American cinematic horror and the latter film catapulted a largely unknown performer by the name of Boris Karloff to the status of motion picture super-star. Karloff’s cadaverous appearance and extraordinary body movements in the non-speaking role of Dr. Frankenstein’s nameless creature captured the attention of critics and made the studio eager to exploit their new star discovery. After the release of Frankenstein, Karloff appeared in no less than nine films for other studios (including United Artists’ gangster classic Scarface)before making his next screen appearance for Universal in an adaptation of J. B. Priestley’s Benighted, released in October 1932 under the title of The Old Dark House. The role of the brutish butler Morgan in that film provided Karloff with some sparse dialogue and an opportunity to project menace under the capable direction of James Whale and with the aid of a make-up designed by Jack Pierce. But it would fall to his performance as Im-Ho-Tep in The Mummy for the actor to present for the first time his trademark persona as an intelligent, articulate and utterly ruthless screen villain.

Not long after the success of Dracula and Frankenstein registered in the front offices at Universal, Carl Laemmle, Jr. , the studio’s vice-president in charge of production, concocted the idea of capitalizing on the popularity of the Tut find and its ancillary “curse” to create a new horror movie that would feature the talents of Boris Karloff. With a treatment in hand by Nina Wilcox Putnam and script department head Richard Schayer, Laemmle announced the studio’s plans in March of 1932 to film Cagliostro with Karloff cast in the title role. Cagliostro, bearing the thinnest of plots, tells the tale of a deranged 3,000 year old sorcerer who, betrayed by his lover in ancient times, spends eternity avenging himself by murdering women who bear a resemblance to her. Like some cut-rate sausage manufacturer, Cagliostro prolongs his shelf life by injecting himself regularly with nitrates. In early summer the studio assigned John Balderston, who’d been instrumental in adapting both Dracula and Frankenstein for the screen, to expand the Cagliostro treatment into a full blown screenplay.

Balderston, who earlier in his career had been a newspaper correspondent, was present when Howard Carter, leader of the expedition that unearthed Tutankhamen’s tomb, reentered the tomb in 1923 to begin the difficult yet exhilarating task of cataloging its contents. Given his unique insights into Egyptian lore, Balderston transformed the Cagliostro treatment into the film that we’ve come to know and revere as the horror classic, The Mummy. By the time the screenplay was completed and the cameras began to roll in September 1932, the property had undergone retitling from Cagliostro to The King of the Dead, then to Im-Ho-Tep. The title The Mummy was not fully decided on until the film was well into production. Also abandoned was the treatment’s pseudo-scientific theme of prolonging life through the use of nitrates in favor of a purely occult means involving the mystical powers of the ancient gods.

The cinematic Im-Ho-Tep, like his real life counterpart, is a lector-priest. While the genuine article was an individual possessed of great virtue and profound wisdom, the Im-Ho-Tep of film is obsessed with and corrupted by love, driven to mad acts of blasphemy and ultimately transformed by his fixation into an inhuman monster. How could such a thing so pure as love have gone so horribly wrong? Balderston provides the rationale in two ways: that the love between Im-Ho-Tep (Karloff) and Anck-es-en-Amon (Zita Johann), daughter of King Amenophis (James Crane), is forbidden by virtue of station; and that at the height of their affair, Anck-es-en-Amon is stricken by illness and dies. Grieving and clearly not in his right mind, this venerated high priest of the Temple at Karnak defies the gods and dares to appropriate the sacred Scroll of Thoth for the purpose of resurrecting the corpse of his dead lover. Caught in this act of impiety, Im-Ho-Tep is buried alive in an unmarked grave, to be lost in the shifting sands of time and desert.

Thirty-seven centuries later, in 1921, an expedition to the Valley of the Kings finds the unmarked grave, the mummified remains of Im-Ho-Tep and the forbidden scroll. The ancient stories say that it is with this scroll that Isis, the goddess of fertility, resurrected her brother and husband Osiris from the dead after he was slain by their brother Set (or Seth—the Egyptian equivalent of the devil). Incest and murder were, apparently, common pastimes among the ancient deities. According to some versions of the myth, upon his death the god Anubis swaddled Osiris’ corpse in bandages, thus making him the first mummy, upon which Osiris assumed dominion over the underworld and became the arbitrator of the dead. In another version there was no intervention by Anubis, and Set dismembered the body, burying its parts throughout Egypt.

Among the archaeologists in the expedition just one man, a Dr. Muller (Edward Van Sloan), who is versed in matters of the occult, seems to grasp the danger in reading the scroll. He invites Sir Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron), the leader of the expedition, outside to discuss the matter under the stars of Egypt, leaving behind Whemple’s young assistant Ralph Norton (Bramwell Fletcher). Norton can’t resist temptation and impetuously opens the casket containing the scroll to begin its translation. As Norton utters the words he transcribes into English, Im-Ho-Tep slowly opens his eyes. In an incomparable moment of breathless cinematic horror the mummy gradually stirs from his sleep of centuries and reaches out a slender hand corrupted by the rot of the eons to snatch away the scroll. When Muller and Whemple return they find Norton laughing maniacally and both the body of Im-Ho-Tep and the sacred scroll nowhere in sight.

Time passes. It is now 1932, eleven years later, and Sir Joseph’s son Frank returns to the desert with his colleague, Professor Pearson (Leonard Mudie), but their quest for Egyptian antiquities proves fruitless. Seemingly out of nowhere a curiously reserved stranger named Arbath Bey appears and leads them to the tomb of the Princess Anck-es-en-Amon. Unbeknownst to Frank Whemple, Ardath Bey is the transmogrified Im-Ho-Tep and he is, literally, hell-bent on restoring the corpse of Anck-es-en-Amon to life.

The remains of the princess and her possessions are transported to the Cairo Museum where the princess’s mummy is put on public display. One evening Im-Ho-tep steals into the museum and attempts to resurrect his dead lover but her mummy crumbles to a pile of empty rags signaling that her soul has been reincarnated in the body of a contemporary woman. It now resides within a dark and troubled beauty of an Egyptian descent named Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann). Helen, quite coincidentally, is under the care of Dr. Muller. The paths of Frank and Helen cross and they begin to fall in love, but ever lingering near at hand is the sinister Ardath Bey, aided by a massively powerful Nubian servant (Noble Johnson). Bey uses telepathy to lure Helen to his home where he reveals the details of their love affair of ages past and of their respective deaths.

Before Ardath Bey can successfully complete his psychic seduction of Helen, Sir Joseph and Dr. Muller piece together the fact that Bey and Im-Ho-Tep are one in the same. In retaliation Bey strikes Sir Joseph dead with his telepathic powers. Frank and Muller make their way to the museum where Bey has taken Helen with the intention of stabbing her to death so that he may resurrect her as an immortal mummy like himself. Helen comes to her senses gradually as she considers the terrible prospect of ending her life in order to attain immortality. Now more Anck-es-en-Amon than Helen Grosvner, the woman, terrified and confused, runs to the nearby statue of Isis and pleads for her help as Frank and Dr. Muller burst in. The arm of the statue miraculous rises and from the ankh that it holds in its stone hand a bolt of lightning issues forth reducing Ardath Bey to a pile of dust and bones.

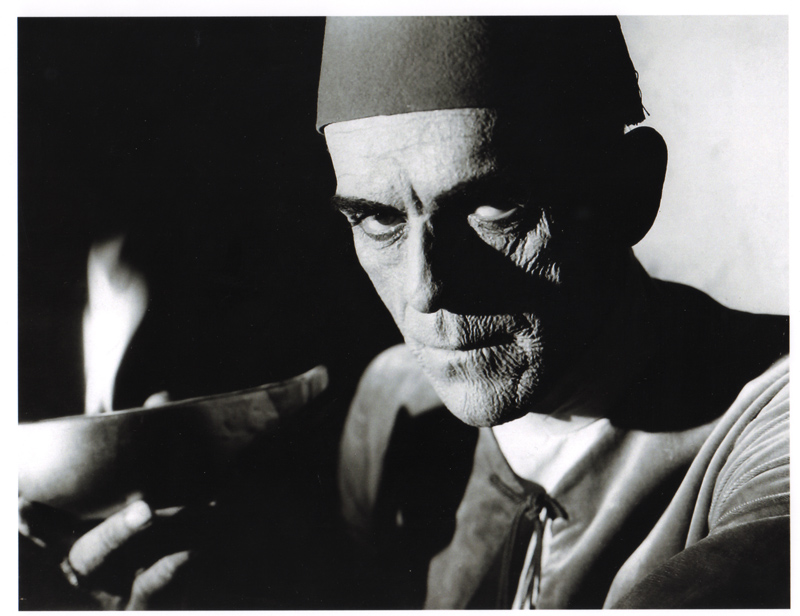

As cinematic art The Mummy plods along at a deliberate pace, one that is almost certainly too slow for most modern viewers to appreciate, yet it is in this methodical pacing, or more specifically the film’s subtle understatement, that its pervading aura of creeping supernatural dread resides. Some contemporary film goers complain about how lethargically Karloff delivered his lines and how theatrical The Mummy is in terms of its acting and staging, yet it is precisely because of these qualities that the film is so well regarded. Indeed, it does not have the artistic sensibilities of a modern movie, but then it isn’t a modern movie—it was made eighty years ago. To its great credit it has a lush visual quality, due in large part to the efforts of cinematographer Charles Stumar and director Karl Freund who was himself one of the great cinematographers of the day and art director Willy Pogany, a well-known illustrator who designed many of The Mummy‘s props and sets. It also has two of the most extraordinary make-ups of Jack Pierce’s already extraordinary career those being for both of Karloff’s on-screen personas. The face of Ardath Bey is as parched as the arid wastelands from which he mysteriously materializes, crisscrossed by a web of wrinkles that divulge great age and exposure to the desert sun, yet it is significantly less degraded than the frightful visage of Im-Ho-tep.

Despite its critical and financial successes it took Universal eight years to capitalize on The Mummy by making a sequel. 1940’s The Mummy’s Hand is, of course, not a sequel in the purest sense, although it does retain most of the first film’s basic plot elements and incorporates some of its original footage. As part of Universal’s second—and to my mind substantially more engaging wave of “classic” horror films, The Mummy’s Hand is an almost perfectly realized, modestly budgeted studio picture. It offers a solid script, a lively pace, dynamic sets and crisp cinematography. It also has some good workmanlike performances and even a few exceptional ones: most notably those of George Zucco, Cecil Kellaway and Eduardo Ciannelli and another standout make-up by the brilliant Jack Pierce. This film was the first of a four-picture cycle featuring the character of Kharis.

Kharis (Tom Tyler) is a prince and like Im-Ho-Tep he is love struck. His affections are for the Princess Ananka, a daughter of King Amenophis. Like Anck-es-en-Amon (who is also a daughter of Amenophis, but in the first film that Amenophis lived 700 years earlier), Ananka becomes ill and dies. The Prince, virtually insane with grief, seeks a quantity of forbidden tana leaves leaves that possess the power to restore life to the dead when prepared according to a sacred ritual. The leaves are harvested from a low shrub once indigenous to the Egypt of 3,000 years ago, but that is now quite extinct. While attempting to steal the leaves, Kharis is caught and he is buried alive after having his tongue cut out. Shortly after his burial in an unmarked grave somewhere in the trackless desert, Kharis is retrieved by followers loyal to Ananka and he is brought to another location where he is kept alive on a diet of tana leaves brewed and administered to him during the cycle of the full moon. As if his original punishment were not enough, he is thus fated to spend eternity protecting the tomb of the princess from desecration.

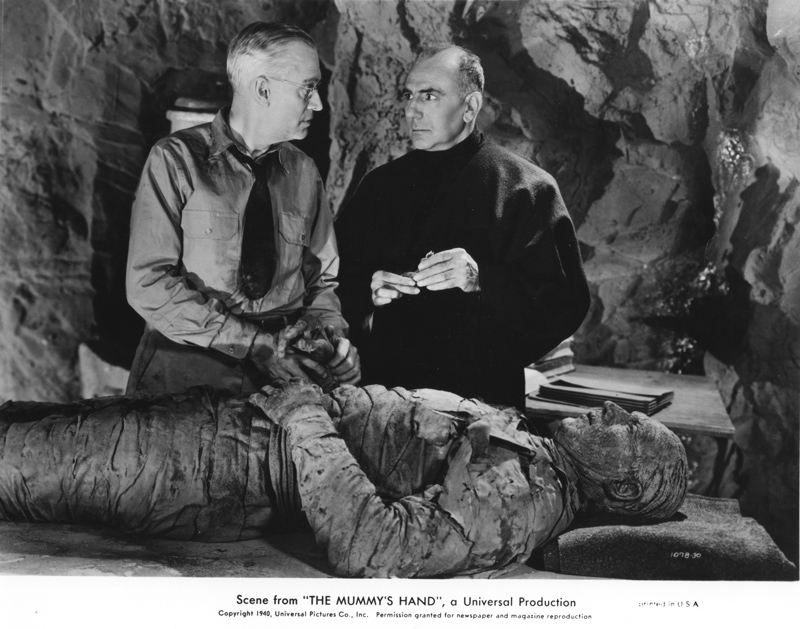

That is until ambitious young archaeologist Steve Banning (Dick Foran) and his sidekick “Babe” Jenson (Wallace Ford) discover an urn with markings that appear to be a diagram of Ananka’s mountain tomb. Steve and Babe talk a gullible magician known as the Great Solvani (Cecil Kellaway) into financing an expedition. Solvani, whose real name is Tom Sullivan, Solvani’s daughter Marta (Peggy Moran) and another archaeologist, Dr. Petrie (Charles Trowbridge) from the Cairo Museum, join Steve and Babe to complete the outing. Despite numerous missteps the group discovers a chamber in the mountains containing the mummy of Kharis. Dr. Petrie is Kharis’ first victim when museum colleague Professor Andoheb (George Zucco) unexpectedly appears at the site while the scientist is conducting an examination of the mummy’s remains. Andoheb is a high priest of a secret religious cult charged with insuring Kharis’ longevity and protecting Ananka’s tomb from discovery. After administering a solution brewed from tana leaves to Kharis, Andoheb directs Dr. Petrie to detect a slow but persistent pulse in the dormant body. With this terrible discovery, Kharis rises and chokes Dr. Petrie to death.

Andoheb with the aid of his cohorts conducts a campaign to murder the intruders by having his confederates secret phials of tana fluid in their tents as a lure for the hideous walking corpse. Three tana leaves dissolved according to the ancient ritual keep Kharis’ heart beating; nine leaves give him mobility. More than nine will transform him into a raging, inhuman monster of unimaginable ferocity.

Kharis’ attack on Solvani’s tent, though interrupted by Marta’s ear-shattering scream, results in the mummy carrying Marta off to a hidden chamber within the mountain. Andoheb, captivated by the young girl’s beauty, makes the decision to inject Marta and himself with tana fluid, thus rendering them both immortal, but his plan is interrupted by Babe Jenson who shots Andoheb in self-defense sending his body hurtling down the mountain temple’s long flight of crumbling steps. Meanwhile Steve Banning arrives at the chamber through a tunnel that connects Kharis’ tomb with the hidden chamber of Princess Ananka. Finding Marta lashed to the altar, Banning frees the girl but as they attempt to leave, Kharis shambles in. A vessel of tana fluid simmering on a flaming brazier by the altar attracts the mummy’s attention. Kharis reaches for the vessel that contains enough tana fluid to transform him into an irrepressible fiend. Steve shoots the vessel out of the mummy’s hand and as the creature drops to the floor to lap up the spilled liquid, Banning brings the fiery brazier down on the mummy’s form and Kharis is engulfed in flame. With the mummy thus destroyed and the tomb of Ananka finally discovered, the Banning expedition returns home, presumably to live happily ever after. Of course, as is the cardinal rule of the successful horror movie, that doesn’t prove to be the case.

In addition to a well-crafted script by Griffin Jay and Maxwell Shane, stylish cinematography by Elwood Bredell, a great score by Frank Skinner and Hans Salter recycled from The Son of Frankenstein, and its modest but effective art direction by Jack Otterson, director Christy Cabanne and film editor Philip Cahn imbued The Mummy’s Hand with a lightning-fast pace. This trend toward shorter, more briskly paced features would continue at Universal throughout the 1940s and although many of the later films would degenerate into monster rallies, gems like The Wolf Man (1941) and Son of Dracula (1943) would emerge to take their rightful place alongside the studio’s earlier horror classics.

Among this modest film’s best assets are insert shots of Kharis in medium close-up in which his darting eyes are produced through the use of cel animation. The inserts are probably not of actor Tom Tyler, as the cheekbones appear to be those of someone with a broader and more exotic face, but regardless of who’s wearing the Kharis make-up, the costume never looks more convincing or more terrifying than in these briefly glimpsed scenes. They are first shown during the attack on Solvani’s tent and are later repeated at critical points, but in these subsequent appearances neither the background features nor the lighting match the footage in which they’re inserted.

One thing that strains credibility is the breakneck speed at which Andoheb quickly decides to spend eternity with Marta by transforming them both into living mummies. This sudden, all-consuming infatuation seems to be a failing of the high priests and some of the lesser minions of the secret cult as it also befalls Turhan Bey in the first sequel, John Carradine in the second, and Martin Kosleck in the third. It would seem that good, reliable religious fanatics are hard to come by in the mummy movies of the 1940s. So, too, is continuity.

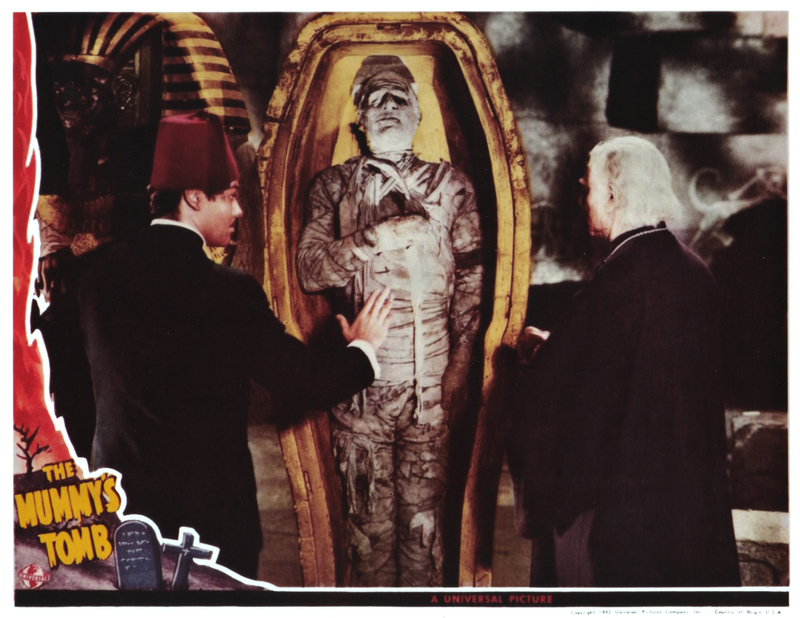

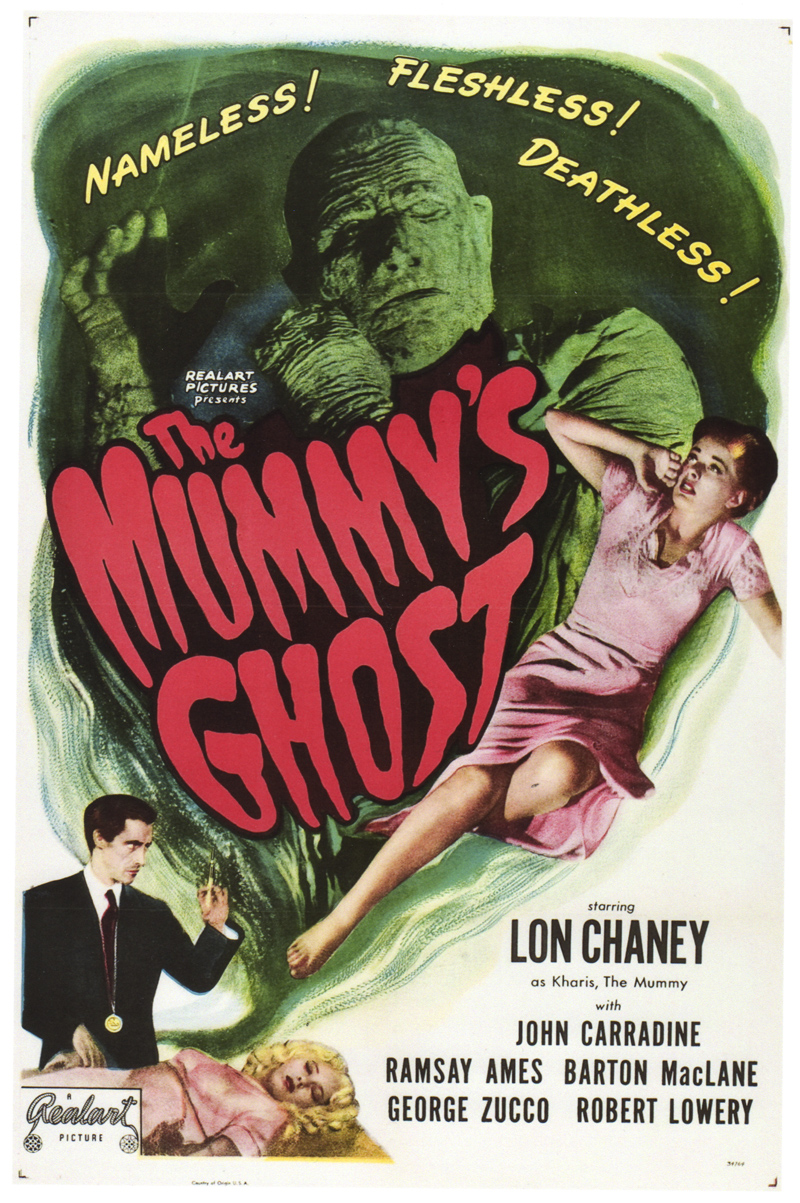

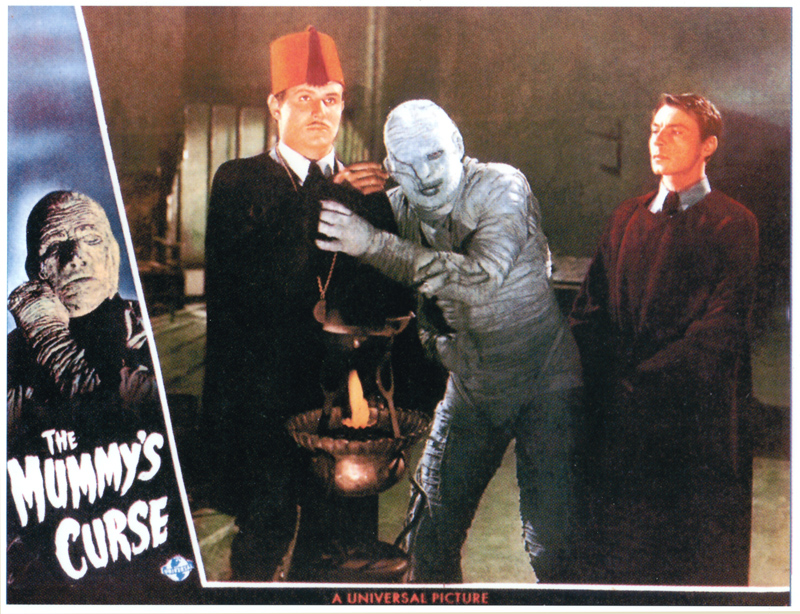

The mummy would be brought to the United States to avenge the desecration of Ananka’s tomb in 1942’s The Mummy’s Tomb, the first of these films to feature Lon Chaney in the title role (actually, the mummy referred to in the titles of both Tomb and Ghost, is probably Ananka’s, not Kharis’s). Chaney insisted from the outset that Jack Pierce create a mask to expedite the make-up application and stop the facial scarring that was taking a toll on his appearance. He is also said to have grown weary of the non-speaking role. The second sequel—third of the series—The Mummy’s Ghost, effectively reintroduces the theme of reincarnation not used since the Karloff film of twelve years early.

In December of that same year (1944), the last, and perhaps least, of the Kharis films, The Mummy’s Curse, arrived in theatres. It begins quite auspiciously with a wonderful sequence in which Ananka’s mummy (Virginia Christine) emerges from a dry swamp bed, but its scant sixty-two minute running time barely allows for the story to get underway before it reaches an abrupt conclusion. The shortest of the Kharis features, The Mummy’s Tomb and The Mummy’s Ghost, both logging in at about an hour in length, are not much longer than The Mummy’s Hand at the other end of the spectrum, which runs to a heady sixty-seven minutes. In spite of that and even though few would declare the Kharis films masterpieces, they are remarkably atmospheric, entertaining and competently made so much so that they stand up admirably to repeated viewing.

They also attracted a small but loyal following made up mainly of viewers who first saw them when Shock Theatre premiered on ABC-TV in the winter of 1957. ABC acquired broadcast rights to the entire Universal horror library and aired a different film every Friday evening at 11:15 PM following the late news. The same feature would be repeated on Saturday in the same time slot, affording true aficionados a chance to see each movie twice, which I, too, faithfully did after meticulously Windexing the TV screen and pulling an armchair up to within a few inches of the television set.

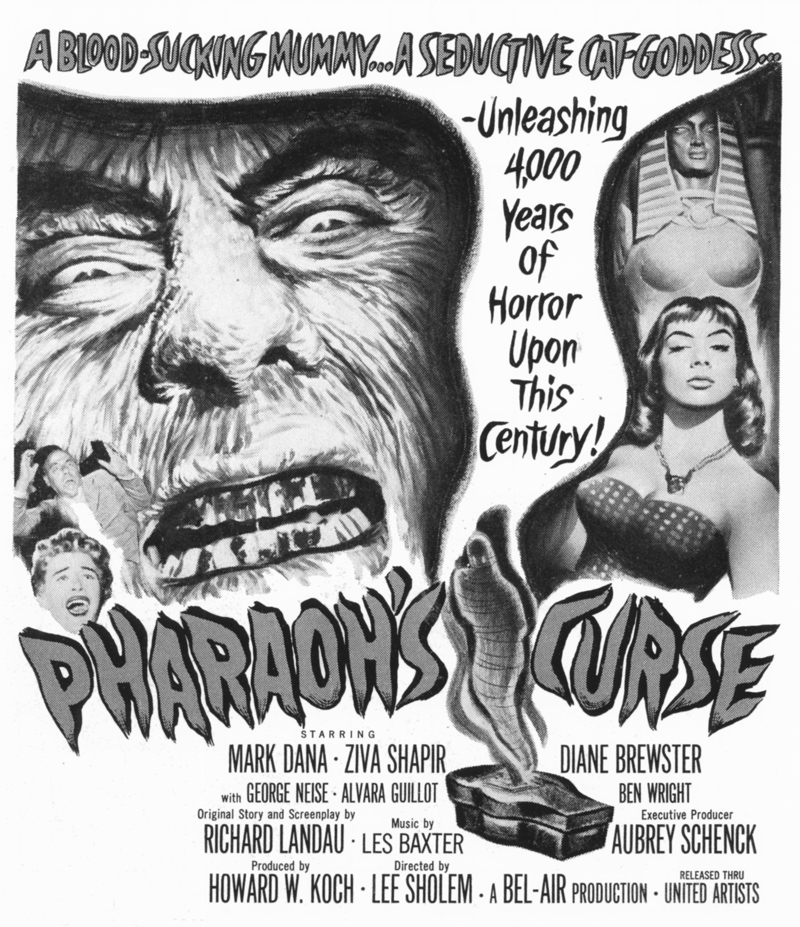

Some months before the premiere of Shock Theatre, during the summer of 1957,I saw my first mummy movie not the mummy, but a mummy at the Loew’s Theatre in Mt. Vernon, New York. It was on the lower half of a twin-horror bill that featured a Karloff vehicle entitled Voodoo Island. Both Voodoo Island and its co-feature, Pharaoh’s Curse, were produced by Bel-Air Productions and released through United Artists. Made on a minimal budget that included footage shot on studio sound stages, in the caves at Bronson Canyon above Los Angeles and in the nearby desert at Death Valley, Pharaoh’s Curse is nonetheless alive with eerie, spine-tingling atmosphere.

The story opens in Egypt in 1902 during the turbulent days of British rule (the British occupied Egypt for forty years, finally granting it independence in 1922, the year of the Tut find). A small party of soldiers is dispatched to find an archaeological expedition that has ventured into the Valley of the Kings without government sanction. It’s leader, Robert Quintin (George Neise), has circled the globe in quest of high adventure, wealth and notoriety and this time he has gone in reckless pursuit of the tomb of Pharaoh Ra-Ha-Teb. In life Ra-Ha-Teb had been a follower of the Cat God Bubasti.

The tomb is a labyrinth of hidden chambers and tunnels and the mummy of the pharaoh’s high priest is interred in a sarcophagus at its entrance. A curse inscribed in hieroglyphics proclaims that whosoever defiles the tomb shall be invaded by the spirit of the high priest—”The flesh of my flesh will crawl into thy body and eat the flesh of thy soul!” As the wrappings are cut away from the mummy’s face, Numar (Uruguayan actor Alvaro Guillot), a young bearer and brother of the mysterious, cat-like Simira (Ziva Shapir), collapses.

Numar rapidly degenerates into a shriveled, blood-drinking 3,000-year-old mummy, skulking about the shadow-shrouded corridors of the mountain tomb. In the ensuing action Numar drains the blood of a horse, attacks and kills two members of the expedition, loses an arm to Captain Storm (Mark Dana) while trying to escape, then finally lures Robert Quintin through a secret doorway where he is crushed to death under several tons of falling rock. Like the mummy films of the 1940s, Pharaoh’s Curse is briskly paced, effective and quite short, at only sixty-six minutes.

The original story and screenplay by Richard Landau suggests a familiarity with the Kharis films of a decade earlier. Although some of the performances are workmanlike at best, the pacing and atmosphere infused by director Lee Sholem and cinematographer William Margulies, and the make-up by George Bau from character designs created by Nick Volpe, go a long way in generating chills and diverting attention away from the deficiencies of acting and dialog. Several scenes between Captain Storm and Quintin’s wife Sylvia (Diane Brewster) in which a love interest is developing are particularly mannered and unconvincing. In spite of that, for me at age eleven, Pharaoh’s Curse was, and still remains, simply unforgettable.

Is it great cinema? Certainly not. Are any of the movies mentioned here worthy of classic status? Well, assuredly one, and possibly more, but as a subgenre mummy movies are much maligned with that often hear phrase that anyone slow enough or clumsy enough to be caught by a mummy deserves to die. Yet there is something utterly and obscenely terrifying about them. Think of that moment when young Norton takes notice of Im-Ho-Tep’s decayed hand clutching at the corner of the Scroll of Thoth. Think of Kharis’s darting eyes as he probes the darkness of Solvani’s tent, or of Amina Mansouri’s once beautiful face as she turns ghastly ancient and sinks into the swamp in Kharis’s embrace. Think of the swirling leaves and the howling wind as the “Mapleton Monster” lumbers large and fearsome through the autumn night. The Mummy, for me, has always been the personification of Halloween—the essence of things old and still and quietly decomposing.

The ritual of brewing an elixir of tana leaves, the quiet, furtive horror of ancient evil lurking below the facade of the seeming normal contemporary world; the quiet New England town where by day all is calm and normal and right, yet at sundown a sinister living shadow walks the windswept night these are the things that give the mummy movies their dramatic power. And while these qualities always lie just beyond the edge of believability, they remind us of the seductive power of make believe, of what it was to be young and alive with the smell of autumn leaves in our nostrils and with Halloween just around the corner.

Vincent di Fate is a science fiction/fantasy artist who’s work spans decades. He has been heralded as “one of the top illustrators of science fiction” by People and has several mantles full of Lifetime Achievement awards from the SFF community.