“The Princess and the Pea” is perhaps Andersen’s most famous tale about a princess, or more precisely, explaining what a princess actually is. That is, a princess is someone who will show up soaking wet on your doorstop and demand that a bed be prepared especially for her particular needs, and then will spend the next day complaining about it, but, on the bright side, the entire incident will later give you a small interesting exhibit for your museum.

Maybe not that much of a bright side.

This is Andersen’s cheerful view of princesses. He did have another one, shared in his less famous story, “The Swineherd.”

Several Andersen fairy tale collections tend to group the two tales together—partly because “The Princess and the Pea” is so short, even by fairy tale standards, and partly because the two tales match together quite well thematically. Originally, however, they were not written or published together. “The Princess and the Pea” was originally published in 1835, in Tales, Told for Children, First Collection, a small chapbook of three tales that also included “The Tinderbox” and “Little Claus and Big Claus.” It was not warmly received at first, partly because it was so short. The Grimms included some very short stories in their collections, but those—technically—were presented as collections of folktales and oral fairy tales. Literary fairy tales—the ones written by French aristocrats, for instance, or the ones Giambattista Basile wrote in his attempt to elevate the Neapolitan dialect to the status of a literary language — had generally been, well, longer than a page, which “The Princess and the Pea,” for all its cleverness, was not.

“The Swineherd” originally appeared in another small booklet, Fairy Tales Told For Children: New Collection, a good six years later, next to “Ole Lukoie,” “The Rose-Elf,” and “The Buckwheat.” None of these tales proved especially popular, but “The Swineherd,” at least, did attract the attention of English translators—who in turn attracted the attention of Andrew Lang, who decided to include both stories in the 1894 The Yellow Fairy Book, bringing both to the attention of a wider audience. With the option of a couple of different translations of “The Princess and the Pea,” Lang chose the one that kept both the single pea (instead of the three peas used by one English translator) and the ending sentence about the museum (also removed by some translators), ensuring that both elements entered English readings of the tale.

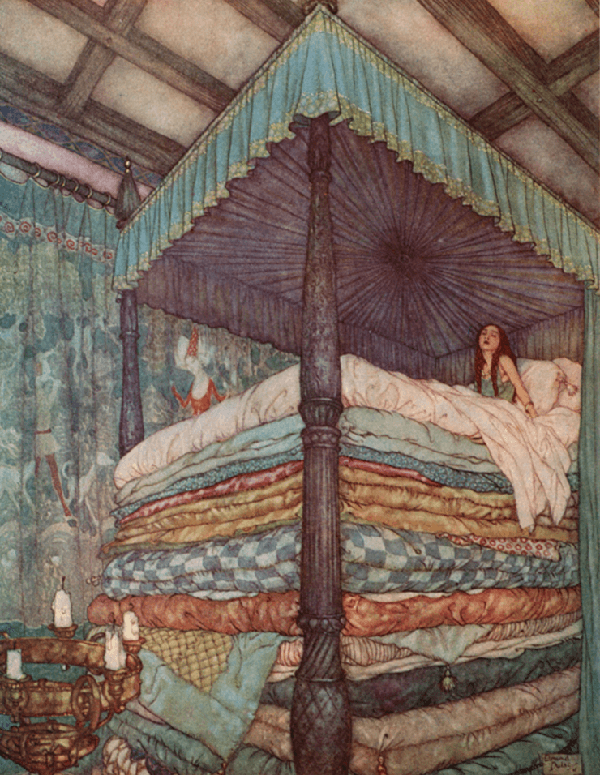

A quick refresher, just in case you’ve forgotten the parts of that tale that don’t involve mattresses: a prince is looking for a real princess, but despite going everywhere, can’t seem to find one—every supposed princess has some sort of flaw showing that she’s not a real princess. I would like at this point to note that most fairy tale princes find their princesses through magical quests and slaying monsters and all that, not just going to other courts in a very judgey way and going, eh, not up to princess level, BUT THAT’S ME. Anyway, luckily for the prince, I suppose, a Real But Very Wet Princess shows up at the door. His mother tests the princess out by putting a pea beneath 20 mattresses and 20 quilts (or feather beds, depending upon the translation; let’s just think heavy thick blankets), which leaves the poor girl bruised. The prince and princess get married; the pea ends up in a museum, and my summary here is nearly as long as the actual story.

As many observers before me have pointed out, it’s entirely possible that the princess figured something was up as soon as she saw that many mattresses and feather beds piled up on the bed offered to her, and tailored her story accordingly. Or, she ended up covered in bruises after she rolled over and fell off such a high bed, and then was in too much pain to sleep afterwards, no matter how many mattresses and quilts and so on. Her story is a touch questionable, is what I’m saying, even if that pea was preserved in a museum.

Also questionable: the origin of the story, which may be original, or may not. Andersen claimed that he’d heard the story as a child, and it does have some parallels in other folktales. The origin of “The Swineherd” is equally questionable: it may be original, but it echoes several tales of proud princesses who refuse their suitors. It’s also possible that Andersen may even have read “King Thrushbeard,” collected by the Grimms in their 1812 edition of Household Tales, prior to writing his proud princess tale.

“The Swineherd” begins by introducing a poor prince who wishes to marry the daughter of the emperor. It doesn’t seem quite hopeless—he may not have a lot of money, precisely, but he does possess a nearly magical rose and a nightingale—two very familiar motifs in Andersen’s tale. Alas, the princess is disappointed in the rose, at first because it is not a cat (I feel many readers can sympathize with this) and then because—gasp—the rose is not artificial, but real (something I feel fewer readers might sympathize with). She is equally disappointed in the nightingale, for the same reasons.

Andersen had ventured into several aristocratic houses and argued with other artists by the time he wrote this tale, and in the process, gained some very definite thoughts on the superiority of the real and natural to the artificial, something he would most famously explore in his 1844 tale, “The Nightingale.” Some of this was at least slightly defensive: Andersen’s initial tales were dismissed by critics in part because they were not deemed literary—that is, in Andersen’s mind, artificial—enough. Which given Andersen’s tendency to add plenty of flourishes—digressions, observations, ironic comments, bits of dialogue from side characters—to his tales makes that particular criticism a bit, well, odd, but it was made at the time, and seems to have bothered the often thin-skinned Andersen.

But more than just a response to his literary critics, Andersen’s insistence on the value of real seems to have stemmed at least in part to his reactions to the industrial revolution, as well as his response to the artwork and trinkets he encountered in the various aristocratic houses and palaces he entered. As his other tales demonstrate, he was also often appalled by the artificial tenets of aristocratic behavior. That irritation entered his tales.

Anyway. The failure of his gifts fails to daunt the prince, who takes a job at the palace as an Imperial Swineherd. Before everyone gets shook about this: Look. Even in the 19th century, aristocracy often paid considerably less than it once did, and this guy just gave up his rose and nightingale. Plus, his job as Imperial Swineherd leaves plenty of time for him to create magical objects, like a pot that allows the user to know exactly what is getting cooked in every house in the city. AND it plays music.

This, the princess wants. The swineherd prince demands ten kisses from the princess in return—and gets them, although the princess demands that they be concealed by her ladies-in-waiting.

The swineherd prince next creates a rattle, which turns out to be less a rattle and more a music box, but moving on. He demands one hundred kisses for this one. And this time, he and the Princess are caught by the Emperor—who tosses the two of them out of the kingdom. At which point, the annoyed prince notes that the princess refused to kiss him when he was a prince, offering roses and nightingales, but did kiss him when he was a swineherd, offering toys. Toys made by his own hand, I should point out, and, honestly, prince, at least this way you know that she wasn’t after your title, but after the things that you could make, which, long term, is probably much better. And you’ve already kissed her, at this point, (pauses for a bit of addition) ninety-six times. I mean, how bad could these kisses have been, really, given that you demanded more after the first ten?

Apparently pretty bad, since the prince deserts her, slamming the door in her face, leaving her alone.

Harsh.

So let’s compare and contrast for a moment here: show up wet and soaked at the doorway of a palace with no identification and then have the nerve to complain about the huge bed provided to you that evening = marry a prince, live happily ever after, and have the entire exploit and the pea preserved in a museum. Decline gifts you didn’t ask for but agree to pay for things you want—ok, granted, in kinda sexual favors, but still—find yourself exiled and alone, without a prince.

Fairy tales. Am I right? Fairy tales.

Or perhaps, in this case, just Andersen.

And no, it does not escape my notice that the princess who heads to bed alone (the pea doesn’t count) lives happily ever after, while the princess who kisses someone of a decidedly lower stature (or so she thinks) does not. It’s hardly an unusual double standard of course, especially for princesses in fairy tales, expected to act like princesses at all times, or face the dire consequences.

Even if wet.

“The Princess and the Pea” inspired numerous picture books, most very funny (the image of the princess struggling to climb to the top of twenty mattresses and twenty feather-beds never gets old), as well as the successful 1959 Broadway musical Once Upon a Mattress, nominated for a Tony Award, and later revived on Broadway in the mid-1990s, and a few minor films. Not surprisingly, given its less happy ending, “The Swineherd” has not been turned into nearly as many picture books, but it has been adapted into a few stage productions, and appears in most Andersen collections, often, if not always, by the story of a true princess. Both are worthy of your time—perhaps especially if you feel a touch of skepticism about fairy tale princesses.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.