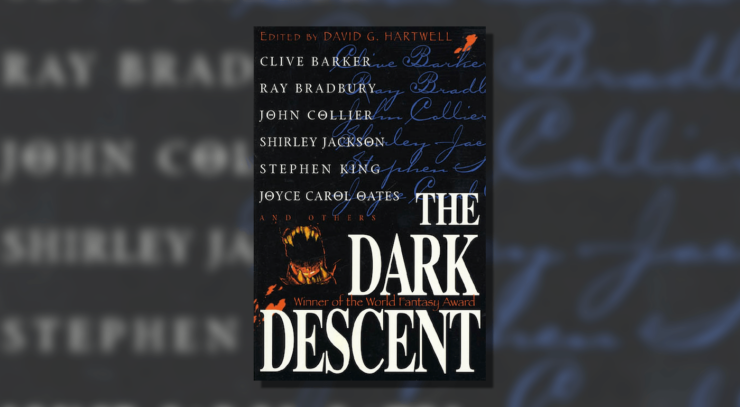

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

“The Autopsy” is about choosing how to live. Michael Shea’s classic of body horror and cosmic terror (adapted recently for Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities in a sickeningly faithful depiction) uses a fatalistic tone, a cynical if grounded outlook, heavy foreshadowing, and stomach-churning visuals offset by clinical detachment to establish a scene where death seems like the inevitable outcome for all involved. While that may be standard for cosmic and existential horror (which describe several of the works Hartwell shuffles into his “moral-allegorical” stream), where “The Autopsy” differs is how it approaches that inevitability.

Where many stories would end things on an equally pessimistic note, Shea instead crafts an ending that manages something of an optimistic note while still maintaining the fatalist tone and gruesome body horror that comes before it. In doing so, “The Autopsy” injects brief glimmers of hope into the usual crushing pessimism of cosmic horror. It remains true to the genre while allowing a twisted sort of triumph, asking the vital question: “If our end is inevitable, how do we use the moments we still have?”

On a lonely night in a small mountain town, Winters, a medical examiner suffering from terminal cancer, is summoned by his friend Sheriff Craven to examine a group of miners after a freak explosion in a mineshaft. Upon his arrival, things are already more complicated than they seem—one of the miners was wanted for a series of cannibalistic murders and had a strange object that looked like a bomb in his arms when the cave-in happened, and the coroner’s already making nice with the local companies who want to get the investigation shut down quickly so they can resume work without paying any insurance. As Winters examines the miners and their suspected murderer, it’s clear there’s even more to this strange story, and Winters’ lonely work might not be as lonely or as safe as he initially thought.

Fatalism creeps through “The Autopsy.” Winters is introduced talking to his terminal stomach cancer, the major events of the story (the murders, cave-in, and most of the investigation) all take place well before Dr. Winters started his examination of the bodies, and even the monster spends much of the story trapped inside a corpse. Sheriff Craven even seems more bitter than angry over the fact that he’s lost deputies during the murder investigation, but understands that pretty much everyone he had to be angry at died in the collapse. By the time the most violent events happen on-page, most of the fighting is already over. Even the autopsy itself seems like a kind of formality—Winters is the second medical examiner to arrive on the scene. Most of the deaths are already seen as accidental thanks to the cave-in, the mining company wanting the investigation to end quickly, and the supposed bomb. Even Winters’ last desperate fight against the monster is more of a series of moves made out of brutal desperation, flailing against the inevitable, than any solid way of defeating the creature.

It’s in that fatalism that “The Autopsy” also finds its strength. Existential horror as a genre is defined mainly by fighting against an inevitable force—we’ve seen that several times throughout The Dark Descent, whether it’s an ancient child-god, a sinister humanoid hivemind, or the Devil himself—and that’s no different in “The Autopsy,” where the grotesque monstrosity inhabiting Joe Allen believes he has all the angles covered and can make a safe getaway (and eat more humans) in Winters’ body. What no one counts on is that Winters finds his own sickening solution to the problem in one final moment, one thing that stops all the momentum driving him towards resignation to the inevitable in one squirm-inducing scene. Through some brilliant foreshadowing and the running monologue Winters addresses to his cancer, a single choice emerges: Winters will die, no matter what, but by gouging out his eyes and ears to destroy his sight, hearing, and balance, by slicing open his major veins, he can take the parasite with him. He chooses how things will end. In this sickening way, he is neither crushed beneath the larger existential threat nor is he forced into complicity. In his own way, forced up against the wall like so many horror protagonists, Winters condemns the monster to a fate worse than death and ensures its unambiguous defeat.

Buy the Book

What Feasts at Night

For an existential horror story concerned with fatalism, Winters’ choice feels triumphant, even happy… It mirrors the clearly bleak ending of “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” where the compliant heroine survives with a broken spirit and the self-delusion that she’s happy. No, Winters isn’t going to live through the story, but he never was. As awful as it is to watch Winters sacrifice himself, it’s optimistic in the sense that he takes his would-be puppeteer—who’s been taunting him by gleefully describing everything it would do in his body, including the prospect of torturing his friends while forcing him to experience, well, for the sake of not squicking out my readers, “intense pleasure”—down with him. Shea introduces a sense of grim, inescapable inevitability—the terminal cancer, the aftermath of the mine disaster, the way the parasite ensures its host is immobile save for what it needs to finish the transference—and then abruptly undoes that inevitability in the most gruesome way possible, allowing Winters, through luck and his own skill, to end things on his own terms.

In allowing room for this slim ray of hope and happiness while still holding to the tenets of cosmic and existential horror, Shea subverts the usual pessimism of this strain of horror. An unambiguously happy ending would seem cheap and hollow, given the narrative’s dark and gruesome fatalism. Similarly, an ending where the parasite wins would be a waste of the story’s fatalism and the foreshadowing Shea layers so expertly, leading to the moment where Winters self-mutilates in order to trap the parasite (mirroring his cancer in that it’s essentially a clump of rogue tissue that must connect itself to the host body) inside himself. Where much of horror, and particularly horror with an existential component, insists on viewing a single human as a mere speck against a vast, uncaring universe full of monsters, “The Autopsy” replies with a resounding “…so what’s holding us back?” If life is essentially meaningless, if our doom has a set point, what’s stopping us from embracing free will, making all the decisions we can, and fighting for every minor victory in the time we have remaining?

While the solution might not always be as cut-and-dried as Winters’ final stand against a parasitic monster (or as gruesome and fatal), it still provides an interesting question in a landscape of existential nightmares, and that twisted note of optimism is one worth exploring in works of existential horror.

Please join us in two weeks as we explore a beloved English fantasist’s dark side with E. Nesbit’s “John Charrington’s Wedding.”

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Apart from here at Tor.com, their writing can be found archived at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and Tor Nightfire, and live at Ginger Nuts of Horror, GamerJournalist, and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.