In celebration of the 50th World Fantasy Convention’s Toastmaster, Michael Swanwick, Reactor presents a new Mongolian Wizard story about a battle to save Paris from an unexpected new enemy.

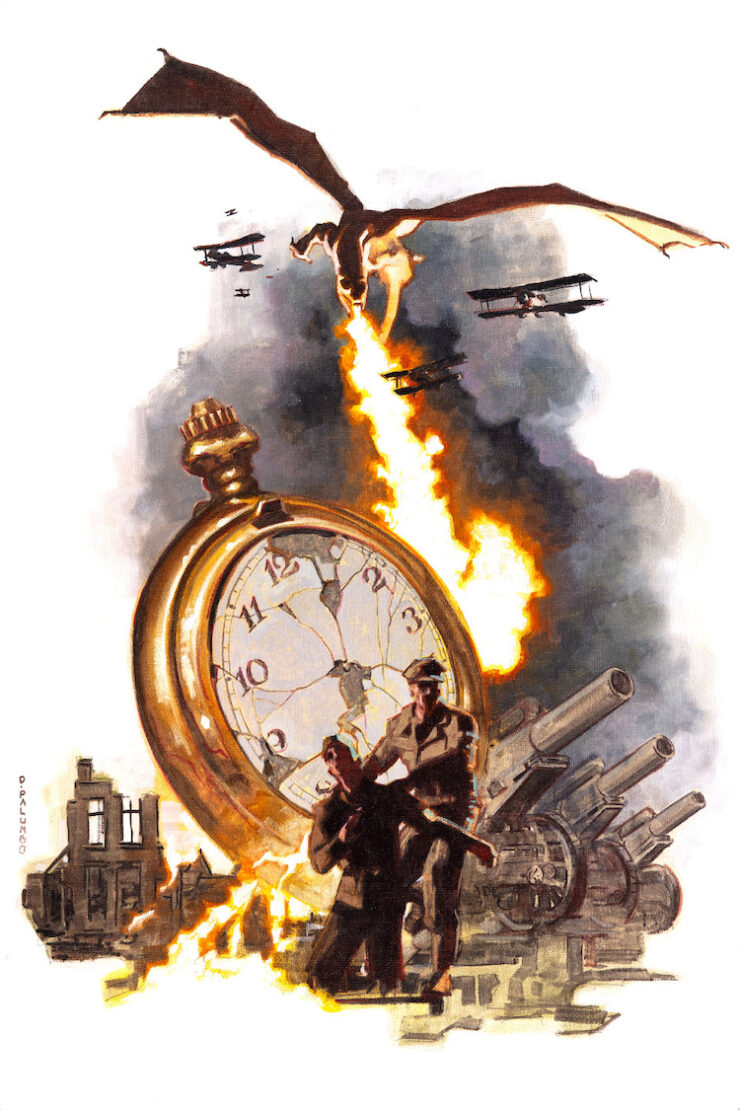

The battle for Paris was expected to be a swift and glorious one. The British forces had committed the bulk of their new mechanized weaponry and the French nearly all their best wizards to a full-bore effort to stop the momentum of the advancing Empire and, with any luck, turn the tide of the war. Indeed, the early stages of the conflict went well. The armored tanks and mobile artillery units devastated the ranks of enemy pyromancers at such a range that they could not effectively respond. Observers in the new aeroplanes, equipped with wireless telegraphy sets, were able to report on the movements of the Mongolian Wizard’s forces as they were deployed. Motor ambulances evacuated the dead and wounded even as the battle was being fought.

But then the giants loomed up above the horizon.

Ritter was in the staging area at the time, watching a necromancer try to interrogate an enemy corpse, to little visible effect. “Canst thou hear me?” the necromancer intoned. “Speak! I do conjure thee by thy very soul, speak!” The corpse lying on the gurney before him did not speak. Turning away in disgust, the necromancer said, “It’s a fucking stiff. The body has to be fresh. But does the Army give two craps? No. They’ll plant a bullet through the left eye, leave the meat out in the rain overnight, and then drag the bloody thing, reeking to high heaven, through the mud to my tent and expect me to make this worm-riddled filth sing like a lorikeet. Fuck it.” Raising his voice, he said, “Haul this turd of a carcass away!” Then, with a sideways glance at Freki, “Or feed it to the bleeding dog, it’s all the same to me.”

“Wolf,” Ritter said.

“As if I care.”

An orderly produced a basin of soapy water and a towel. His superior rolled up his sleeves and began washing his hands.

Ritter glanced at the badges on the corpse’s uniform. A Kadet-Feldwebel. He doubted the necromancer could have gotten much useful information out of a non-com anyway. Attempting to establish a rapport with the man, he said, “So the rumors I have heard that prisoners are routinely killed and then questioned posthumously…?”

“By-your-leave nonsense, of course. If they’re alive, there are far easier means of dragging the truth out of their skulls.”

“I am glad to hear—”

The necromancer grinned nastily. “And they’re a lot more gruesome than mine.” Again, he raised his voice. “Tell the scavengers to send me some fresh bodies! Officers! The higher-ranking the better! Preferably ones that aren’t crawling with maggots and haven’t been shot in the goddamned window-of-the-soul!”

At which moment, the orderly (by his accent, a displaced Swabian), who stood staring out the tent flap, softly said, “Gott im Himmel.”

All turned.

The monsters that loomed up in the distance were not the effete giants, a mere twelve or fifteen feet tall, that were employed by the military to backpack munitions over mountains or wade through swamps where wagons could not go. These were at least a hundred feet high and correspondingly burly. They were not merely men writ large, but primal nightmares such as had been, at great cost, driven out of Europe during the most desperate years of the Dark Ages. They inspired a superstitious awe that went deep in time to the fire-lit caves of Mankind’s origins. The mere sight of them made the hairs on the back of Ritter’s neck stand on end.

There were five in the tent, not counting the corpses and Freki, of course, and of them all only the civilian scryer Peter Fischer did not look astonished at this turn of events. In a mournful voice that suggested he had foreseen all this long ago, Fischer said, “Now we shall witness the single greatest military blunder of this entire war.”

Then he burst into tears.

Half an hour earlier:

Ritter had come to Paris as an observer for British Intelligence. Theoretically, he had full access to the command staff at field headquarters. He was attached to General Garnett, however, and the general considered him to be at best a minor nuisance. So, in the buildup to the battle, while command was focused on the logistics of deployment, Ritter was sent off on a make-work intelligence gathering assignment. Which made it ironic when, passing by FHQ on his way to the tents where the necromancers were at work, he ran into Peter Fischer leaving it.

Fischer was trying to appear brave. It was, on him, not a convincing look. Beneath his assumed bravado, he seemed to be very, very depressed. Which, knowing the man, Ritter found far easier to believe.

“Herr Fischer! I met you when I performed the investigation at Yarrow House,” Ritter said heartily, shaking his hand. In a low, emphatic whisper, he added, “What the devil are you doing here? You should never be this close to enemy lines.” Fischer’s head contained the greatest secret of the war—the source of Britain’s astonishing new weaponry. And that head was a very poorly defended fortress indeed.

“Well…Lord Greystoke, you see. He’s on the—”

“I know who Greystoke is. What idiocy has he committed now?”

“He wanted a scryer near the general staff. To spy on the enemy, he said, but clearly he wouldn’t mind knowing what our allies were up to. He stipulated we send our best man. Which was me, obviously. Sir Toby tried to dissuade him. But you know what Stinkers is like when he gets a notion.” Like many Oxonians, he tended to assume that everybody knew the old school nicknames. Fischer shrugged and said, “So here I am, in the thick of the war, where I once foresaw my own death. My only consolation is that my work has made such visions less reliable than they once were.”

Time skipped.

Fischer shrugged and said, “So here I am, in the thick of the war, where I once foresaw my own death. My only consolation is that my work has made such visions less reliable than they once were.”

Time skipped.

Fischer shrugged and said, “So here I am, in the thick of the war, where I once foresaw my own death. My only consolation is that my work has made such visions less reliable than they once were.”

Then, with a frustrated stamp of his foot, Fischer cried, “There! You see? Looking into the future is one thing but using that ability to create weapons that won’t be invented until long after we’re dead is chronologically destabilizing. The old reality keeps trying to restore itself. And since I am at the center of the project, naturally the effects cluster about me.” Discretion forgotten, he was no longer whispering.

“These are not matters that should be discussed out in the open,” Ritter said. Then, for the sake of anyone watching, he gave Fischer a hearty slap on his back. “Be a man! Show some spirit.” Quietly again: “Sir Toby assures me that the weaponry your division has brought back from the future will make this battle an easy victory.”

Fischer’s face grew even more melancholy. “Do you really believe that?”

“To be honest, not really. Still, we can hope.” In front of staff headquarters, with high-ranking officers of a dozen loyalties coming and going, was the worst possible place for Fischer to be in violation of the Official Secrets Act. So Ritter said, “Come with me. I’m off to watch the Necromancer Corps interrogate enemy corpses. Perhaps we will learn something there that will prove useful.”

He called Freki to his heel.

“I might as well,” Fischer said. “I’m not doing any good here. I gave the general staff a formal presentation—with bullet points!—detailing what I foresaw and they called me a coward and cut me off before I could get to the gist of my argument.”

Back in the present:

While the others were staring, gape-mouthed, at the giants, Ritter drew Fischer to the back of the tent, where they would not be overheard. “Tell me about this military blunder,” he said. “It is all right. No matter what you know, I have clearance to hear it.”

Peter Fischer nodded. “Yes. Yes, I…Yes, that makes sense. Let me gather my thoughts.” He closed his eyes in concentration. A long silence ensued.

Ritter was beginning to wonder if the man would remain mute forever when Fischer screamed, convulsed, and fell to the ground in a seizure. His eyes rolled back into his head and his jaw quivered so that his teeth clattered.

At which very instant, the artillery went into a frenzy, every gun firing and firing and firing, thunder upon thunder, until it was impossible to hear, impossible to speak, impossible to think, impossible almost to breathe. It was just barely possible for Ritter to kneel by Fischer’s side to clear away sharp or heavy objects from his thrashing arms. Ritter took several hard blows doing so, but was able to protect the scryer nonetheless.

The shelling seemed to last forever. It was all-encompassing, a world of its own, a universe in which men might live, work, love, raise children, grow old, go senile, and die, leaving behind another generation to do the same while the cannonade continued on and on.

Though his attention was chiefly focused on Fischer, Ritter occasionally managed a quick glance through the open door flap at the battlefield, shrouded in cannon-smoke, and beyond it the still-approaching giants. The guns were firing blindly, it seemed, though every now and then one of the titans fell as slowly as a distant avalanche. Still the cannons roared. At last the giants could not be seen through the smog of war. But the artillerymen, lost in panic, continued shelling their unseen foes. A mounted officer rode down the line, gesturing wildly and, apparently, shouting at the gunners. Some he actually stopped to pull away from their cannons. But it did no good. The shelling continued until all the ammunition was depleted.

Everything went still.

The horizon was empty of giants.

The soldiers lifted rifles and pumped fists in the air in celebration.

Peter Fischer’s seizure had come to an end. Ritter stood up. His ears were ringing and there was so much gunpowder in the air that he knew for a certainty he would soon have a headache. Freki was shivering in fear and anger; nothing in his training had prepared him for such noise. Ritter kept a light mental leash on the wolf’s mind, less control than reassurance, a reminder that his master was with him. Freki would collect himself soon enough. Then he saw Fischer’s eyes flutter open and helped him to his feet. Fischer’s mouth moved.

“What?” Ritter said, as loudly as he could.

“We will need those guns before this day is over. But they will have nothing to fire.” Fischer shouted too, yet his voice sounded weak and distant.

“You foresaw that?” Ritter wanted to strike the man. “Why didn’t you tell someone?”

“I tried. They wouldn’t listen.”

There was a time to tell the truth and a time to be reassuring. “Not everything a scryer sees comes to be. Let us hope this is one such case. Come with me. Now that the battle is begun in earnest, we shall watch the action play out as the generals do—on a paper map atop a table.”

Unhappily, Fischer followed him out of the tent.

All the way to FHQ, soldiers were in motion, assembling, receiving orders, marching out. The troops left and left and left, without in any way diminishing the numbers of those who remained. Across the tabletop of the world and the paper map of the battlefield, the allied armies were on the move. In the wake of the fall of the giants, their mood was almost buoyant. Things were going their way. The enemy lines were wavering and looked to be on the brink of giving way.

Surely, destiny was on their side.

As he had foreseen, Ritter had a headache. It made Freki irritable and hard to control. So he reached deeper into the wolf’s mind to soothe and calm it before entering the great tent housing the field headquarters. Freki hated crowds, noise, and hysteria. Here, all three would be found in abundance.

In the tent, messengers came and went, all at a run. Aides-de-camp leapt to convert their news to movements of lines of small, brightly colored cubes on a map. Fresh messengers rushed to carry orders to those same cubes. Among the peacock array of generals with their medals, honors, plumes, and sashes, one stood out because he was dressed in a simple olive drab uniform with no decoration other than the seven stars on each sleeve. This was the MaréchaldeFrance himself, sucking moistly on a pipe and scowling down at the map. A dozen or so black cubes, representing the giants, had been swept to one side. But the blue lines of enemy infantry and red lines of warrior wizards obstinately refused to spill backward in a rout.

“Stay here,” Ritter told Fischer just inside the entry. He then reported to General Garnett, who barely recalled what he had been sent to do, but managed to dredge up enough from memory to ask, “What news from the necromancers?”

“They want fresh bodies, sir.”

The general showed a brief flash of teeth. “Let them wait a few hours and they’ll have all they want. I see you have the Prophet Jeremiah with you.”

“Fischer, you mean, sir? I assure you that, distracting though he may be—”

“Whatever his name, your man is Cassandra reborn sans teats. He had the cheek to present a slide talk titled ‘Why We Will Lose.’ Doom and gloom are bad enough without pie charts and bullet points. Let the boffins tend to their business, say I, and we’ll tend to ours—which is winning this war.”

With dismay, Ritter saw that Fischer was shambling toward the general, arm outstretched and a visionary haze in his eyes. “I see you. Your future. I see…”

Barely suppressing a smile, General Garnett said, “Yes, scryer? What do you see in my future? An earldom? A castle? Three fat peasant whores in my bed at the same time?” He winked at Ritter, who did not feel it was appropriate to respond. “What do you see? Eh?”

“I see you losing an arm.” Fisher’s face was white and dripping with sweat. “You will be screaming in pain and they will try to evacuate you in a motorized vehicle. But in so doing you will be placed in the path of an incoming dragon. I see your charred corpse being trampled underfoot in the general rout.”

Garnett drew back in revulsion. “Take this man away from here and never let him within sight of me again!”

“Sir. Yes, sir.” Ritter clicked his heels and turned crisply away.

As he left, Ritter saw the Maréchal deFrance, alone among the officers in his lack of optimism, scowl down at the map and heard him mutter, “What can they be up to? Their deployment makes no sense.”

The middle phase of the battle went about as well as could be expected, given that the enemy had not collapsed after the artillery had blasted the giants into oblivion. Which was to say that it was a long, hard slog with only minimal progress to be shown for it. The enemy’s lines held, though in places they were forced to draw back. Reinforcements were brought forward by both sides. Aeroplanes buzzed about the sky like horseflies. Motorized transit fell prey to an illusion that the marshes by the Seine were solid ground and bogged down in them. The enemy’s cannons punched holes in the allied forces. But those losses were more than compensated for by the armored motor-guns already known to the men as “tanks,” which proved to be all but unstoppable. Weather wizards called down lightning out of a clear sky and one bolt struck a French ammunition dump. The explosion killed everyone for a hundred yards around. Ambulances went out and returned to the medical tents and went out again, like lines of ants on a fine summer day.

The afternoon wore on.

The enemy had no way to match the allied forces’ machinery—but they displayed great ingenuity in trying. Night-hags flew broomsticks in formations of four, with an open wicker cabin that was little more than a basket hung on ropes between them. In each basket was an alchemist and a supply of chemical bombs. Prior to this battle the witches had flown only at night, for they were easy to spot and shoot down in daylight, and from their never being seen, rumors had spread that they flew naked. So when their bullet-riddled bodies fell to earth and were discovered in khaki trousers and blouses, disappointment was widespread.

Ritter found himself in the rare position of being free to do anything he desired save for the two things he wanted most—to fight in the battle or advise the officers conducting it.

“I’m thirsty,” Fischer said, as if this were of any importance.

“I’ll find you water.”

“And I’m hungry. I haven’t eaten anything since breakfast.”

“I’ll see to that too.”

As they were passing by the medical tents in search of food and drink, Ritter was hailed by a woman in surgeon’s uniform who had stepped outside for a cigarette break. “Ritter! Thank goodness, somebody with half a brain.” His heart sped up as he realized that it was Lady Angélique and then subsided when he saw in her no trace of the fondness she had displayed at their last encounter, only days before. In his confusion, he barely remembered to salute. “You must help me,” she said. “I’ve sent messages to the quartermasters, demanding that they give me some of those machines with the ridiculous names—the ones that look inside people—and they claimed they had no idea what I am talking about.”

“Is it important? I have—”

“You don’t understand. Half the labor of a psychic surgeon is reaching inside our patients with our minds and identifying their injuries. If we could hand off that chore to these machines, we could treat twice the number of casualties, and save double the lives.”

“I am sorry but I have never heard of these devices.”

“X-ray machines,” Fischer said unexpectedly. “Twenty were shipped here but they haven’t been uncrated yet.”

“Yes! That’s the name! I wish there were a hundred but twenty is a good start. They must be sent for immediately.”

Fischer stared down at the ground. “Ah. Well. They’re no good without trained operators, and only one was sent. She died of dysentery, I’m afraid. I wrote a memo warning that would happen, but it was ignored.”

Lady Angélique threw down her cigarette and ground it underfoot as if it were the bureaucrat responsible for the snafu. Without a word, she dove back into the tent.

Ritter stared after her. Without makeup, her hair tied back in a simple bun, Angélique looked haggard and weary and absolutely beautiful.

Hours passed, with great carnage on both sides. Fischer grew paler and sweatier and sometimes foxfire danced about his head in a pale blue aura. “I need a place to lie down,” he said.

“I’ll find something for you,” Ritter promised. In need and helplessness, Fischer was very like a child. Ritter knew that the man’s well-being was paramount. But as the most important battle of the war—and probably of Ritter’s life—unfolded without his participation, he found himself wishing he could simply shoot the fellow and return to proper soldiering.

Then the dragons came.

It had been so long since dragons were employed in warfare that most people believed them extinct. But the Mongolian Wizard, or his people, had evidently found a feral strain living somewhere in the wilds of Siberia, tamed them, trained them, and then held them back from conflict until the right moment.

Which had arrived.

The enemy’s strategy was now manifest. The long-range artillery guns, which could easily have shot the dragons out of the air, were silent, for their munitions had been depleted. Terrifyingly large and yet an easy target for modern weaponry, the giants’ sole purpose had been to waste the allied forces’ shells. A task they had performed brilliantly.

For a bleak moment, Ritter felt despair. But such thoughts were unmanly; rejecting them, he racked his brains for some way to counter the oncoming dragons. There must surely be one! There was an answer for any problem, if only it could be discovered in time. Then he remembered the aeroplanes. “What a fool I am!” He turned to Fischer. “We must report to the general staff.”

FHQ, however, had anticipated his thought. By the time he was halfway there, the aeroplanes were already taking off. Row upon row of what had to be the entirety of the allied air forces lifted into the sky, engines snarling like hornets. Ritter watched them dwindle to the size of gnats and then heard the popcorn sound of their Vickers machine guns in action.

Ritter wished with all his being that he were on one of those planes. The battlefield, be it ground or sky, was the place for men: body, brain, and bravery pitted against the cold logic of fire and bullets and wizardry, with the victory going to he who kept the calmest and fired last. By contrast, Intelligence seemed an ignoble thing, an occupation for weaklings.

“If you were up there now, you wouldn’t return alive,” Fischer said.

Ritter started. Then he laughed mirthlessly. “I forgot that you can read minds.”

“I cannot read minds. But I can read faces and yours is easier to read than most. You think the dragons can be slain because they must. I, alas, know what is coming.”

The aeroplanes converged upon the dragons and were met with flame. Though the courage and skill of their pilots was undeniable, one by one the flying machines kindled and burned and dropped from the sky. Crisped and blackened bodies plummeted. If a man managed to get free of his aeroplane, his attacker looped around to torch his parachute, leaving him to fall, trailing shreds of burning silk. The dragons appeared to enjoy the game.

When the sky was empty of machines, the dragons flew low over the allied armies, spreading fire and terror wherever they stooped.

One broke from the pack and made straight for the allied encampment. Though many shot at it, it appeared to be immune to small arms fire. Low over Ritter it flew, foul-smelling and armor-scaled, spewing fire to either side. In its wake, men burned like candles.

Historical accounts of dragon massacres all included the terrible injuries and the screams of the dying. But they omitted the sweet, sickening smell of roasting human flesh. They described the horror but left out how one’s mouth watered for barbequed pig afterward and the self-loathing that engendered.

Now Ritter knew—and despised himself for it.

There were fallen bodies everywhere. Some soldiers crouched over the survivors, doing what they could to help. Others fled in panic.

At such a time, Ritter must be at his post. Staring up at the sky, he began walking toward FHQ.

“You’re about to trip over a corpse,” Fischer said.

Ritter tripped over a corpse. Ahead, the tents housing the general staff loomed up before him. Then the dragon made a second pass over it and with a roar the canvas went up in flames.

Against all odds, the first person Ritter saw when he reached FHQ was his CO, General Garnett. The general was being loaded onto a stretcher by two junior officers. As Fischer had foreseen, he was screaming in pain and one arm was so badly burned it was obvious he would lose it. A third soldier was bringing up an ambulance, leaning out the window to shout obscenities at those in his way. Behind them all, the tents crackled merrily.

Ritter had sufficient rank to take command. But the men were handling the situation calmly and capably. He stood back to avoid interfering with their work.

Not so Fischer. “The general can still be saved,” he said, plucking at one soldier’s sleeve. His eyes were moist with tears. “Forget the ambulance. Run him over to the field surgery unit on foot. The dragons won’t attack there—the Mongolian Wizard has orders to seize all the medical personnel that can be found.”

But the soldiers, ignoring what they obviously thought a madman, loaded the general into the ambulance, and drove him directly into the third pass of the dragon.

Fischer was crying now, openly and without shame. “They never listen to me,” he said. “Why do they never listen?”

The allied armies were in disarray. Meanwhile, the Empire’s forces advanced steadily, maintaining a disciplined advance. Their commanders, knowing what was to come, had held their best forces back. Now they were unleashed, and the allies fled before them. Orders were given to evacuate the encampment—unnecessarily, because it was already being abandoned.

Amid the chaos, only Ritter and Fischer stood their ground—Fischer because he had already seen what was coming, and Ritter because he knew his duty. Freki crouched at Ritter’s feet, fearful but trusting that his master would protect him. Fischer stared straight ahead at nothing, lost within his own dark thoughts.

Wars were lost and won as much by how an army handled its defeats as by its victories. Ritter understood that. The allies had been outwitted and outmaneuvered. But perhaps the damage could be minimized. He must do what he could using whatever tools were at hand, to bring that about. Ritter’s own abilities to affect the outcome of the battle were minimal. But Fischer was Britain’s best scryer. He had said so himself. Therefore he must be put to use. Unfortunately, he was by now almost catatonic.

To get the man’s attention, Ritter shook him. “Listen to me. Listen! Is there still hope? Tell me there’s hope.” He slapped Fischer’s face, not one half so hard as he’d like to. “God damn you, must I beat you to death and hand you over to the necromancers?”

“It’s no use deserting,” Fischer said, in a dazed voice. “We would be caught and hanged.”

Hiding his disgust, Ritter said, “We will not desert. Paris must be preserved. Tell me there is a way to keep the Mongolian Wizard from taking it.”

The aura blazed up around Fischer so strongly that it looked like his hair was on fire. He turned dead eyes toward Ritter. His mouth moved soundlessly. He swallowed and tried again. “I…yes. Yes, there is a chance. Maybe. A slim one, but…If—”

At that moment, four night-hags flew overhead. From his wicker cabin their alchemist flung a hexed bundle of metal scraps and screamed a trigger word after it.

The metal exploded into shrapnel.

After a bit, Ritter pulled himself up from the ground, largely unhurt save for a small metal scrap or two lodged in one thigh. Only to find Fischer, still on his feet, staring at a fountain of blood that gushed from where his hand had been. In swift, efficient movements Ritter whipped out his belt, wrapped it around what remained of the forearm, drew it tight, and tied it off. That stopped the bleeding. Then he bent to catch Fischer’s collapsing body and sling it over his shoulders. He had no idea where he was. Nothing looked familiar.

“Which way to the field hospital?” Ritter shouted at a soldier, who spread his arms in incomprehension. He grabbed the man’s shirt, almost losing his grip on Fischer’s body. “Das Feldlazarett! L’Hospital de campagne! Where?”

The soldier pointed. Ritter went.

Staggering into triage, Ritter saw Lady Angélique with her face mask loose about her neck, walking down a line of those deemed suitable for surgery. She looked exhausted. He lay Fischer on the ground before her. “You must operate on this man immediately.”

Without comment, Angélique listened to Fischer’s heart, peeled back an eyelid, ran a hand slowly through the aura that only surgeons could see. “His chances are negligible,” she said. “I won’t waste my time on him.”

“Peter Fischer is important to the war effort.”

“So are we all. Good job with the tourniquet, by the way.” To a male nurse, she said, “Make him comfortable. Morphine, if there’s any left.” Then, to Ritter, “I’m afraid that’s all I can do.”

Lady Angélique turned away.

“Stop!” Ritter seized her arm and spun her around. She being a superior officer, the act horrified him. But he did it anyway. “Fischer is the most powerful scryer we have—he foresaw us losing this battle. But just before he was wounded, he said there was a way for us to save Paris. If you can heal but one man, it must be him.”

“No man is that important.”

“You don’t know Fischer! It would be better that you and I and a thousand more were to die than he. The knowledge in his head is worth any sacrifice. Any at all.” Ritter realized that he was still holding Angélique’s arm. He let her go.

To the appalled nurse, Lady Angélique said, “Prep this one for surgery. I’ll operate just as soon as he’s ready.” Eyes like ice, she added, “If you ever touch me like that again, Ritter, I will have you court-martialed so fast your head will spin.”

This was the death of a brief romance that Ritter had hoped might have become something more. “I understand,” he said. “Thank you.”

The nurse looked up from Fischer’s body. “Ma’am? I’m afraid it’s too late.”

“What?” Ritter said.

“He’s dead.”

If Ritter had but one virtue, it was that he was stubborn as a mule. After Lady Angélique had chosen another soldier to operate on and the nurse had bandaged Ritter’s leg wound—“You’ll bleed out otherwise,” the man had insisted—he threw Fischer’s corpse over his shoulder and went off in search of a necromancer.

By now, everyone, it seemed, was fleeing. Ritter struggled against the flow of human bodies. With the armies in full retreat and FHQ ablaze, the camp had tipped over into anarchy. Here and there, a charismatic officer held a squad or platoon intact—but only to perform an orderly retreat. When at last he reached the Necromancer Corps’ tents, they had been evacuated and set afire.

“Hey, pal—spare a fag?”

The soldier asking the question, an English private, was lolling in the seat of a motorized truck whose bonnet had been left up when whoever was trying to repair its engine dropped tools and fled. Ritter set down his friend’s corpse, bringing his insignia in view. Seeing them, the soldier grinned and added, “Sir.”

Ritter did not himself smoke—it was a filthy habit. But whenever he was at the front, he carried a pack to ease social interactions such as this one. He offered a cigarette and lit it for the soldier who, he noted, had a crushed foot and a three-quarters-emptied bottle of whiskey. The man nodded thanks, took a long drag, and said, “You might want to get going, sir. The enemy is almost here.”

“I need a necromancer.”

“All gone. Orders of the head brass. When the Mongolians overrun a place, the first thing they do is grab the wizards.”

“You are absolutely sure there are none here?” Ritter asked.

“Sure as shit, sir.”

“Then you might want to close your eyes for a minute.”

Ritter unsnapped his holster and drew out his automatic pistol. He aimed down at Fischer’s corpse. Through the eye, the necromancer had said this morning, a thousand years ago. That would render Fischer’s brain unreadable.

He squeezed the trigger.

He could hear the Mongolian Wizard’s advance men roaring up on the encampment in motorized vehicles they had captured from the British in earlier encounters. They would have witch-finders among them who would see his talent burning bright within him. There would be no escaping them. It was his duty in this situation to kill himself. He accepted that.

Far more difficult was his duty to kill Freki. Inside that innocent head, so many secrets were hidden. The right neuromancer, one with a feel for animals, could tease out those secrets, even though Freki did not understand them—and the process would be extremely painful for the wolf.

One shot to the back of Freki’s skull put that possibility to rest.

Farewell, comrade, Ritter thought. You were a loyal soldier. He raised the muzzle of his gun to the side of his own head. For a strange, lucid instant, all the world—the soldier staring horrified from the truck, the corpses of his companions, the blue sky overhead—seemed infinitely precious. Then—

—a lightning bolt struck the ground before Ritter, blinding and deafening him. When he could see again, electricity danced over the battlefield, as if all the world were a Van de Graaff generator. Corpses rose up and danced. Ritter could feel reality shifting underfoot.

There was a tremendous rushing sensation, as if everything were speeding backward at a tremendous rate. The sun slammed from one end of the sky to the other. Shadows wheeled counterclockwise.

And it was morning again.

It was morning again and the battle was unfought, the dead unkilled, the mutilated yet to be disfigured. Only the soldiers were different from the first time around. Where originally they had been buoyant with optimism, now they moved like zombies, stunned by the sudden reversal. Some, doubtless those who had been yanked back from the morgue or the hospital tent, had bleak looks of horror on their faces. In the distance, the enemy was doubtless making preparations to begin the battle again.

“I…seem to have blacked out,” Peter Fischer said. “I didn’t show the white feather, did I?”

Ritter could have hugged the man. Instead, he said, “I will tell you everything later. Right now, you must explain to me exactly what has just happened. Don’t have another of your verdammt seizures! Tell me what you know.”

“Give me a moment, let me think.” Fischer was still. Then he said, “Yes. There is only one explanation. The chronological destabilization I told you about? The charges involved obviously grounded themselves, massively, and so returned us to the beginning of the day. They must have been building for a long time to manifest themselves so strongly.”

“If it makes sense,” Ritter said, “then that is all I need to know. Now tell me what we are to do with this God-given opportunity.”

Fischer did so.

When he was done, Ritter commanded Fischer, as one might have a dog: “Stay here. Wait for me.” Then, to Freki, “Make sure he goes nowhere. If he tries, bite him.”

Freki did not understand his words, of course. But Fischer didn’t know that. Silently, Ritter commanded Freki to stay close to the scryer and protect him. Let them misunderstand each other. All he needed was fifteen minutes.

The mood in FHQ was one of befuddlement. Many there had died and were now reborn. All remembered horrors that had not happened yet. Even the Maréchal de France looked bewildered and uncertain.

Striding forward, Ritter murmured, “Your pardon, Maréchal.” He took the place at the head of the map table where the Maréchal ordinarily stood and raised his voice to assume control of the room. “You have seen what happened. I am not at liberty to explain to you how this miracle was arranged. However, I assure you that we cannot count on it happening again. Do not waste your time on idle questions. You have lived through one of the greatest defeats in military history. Now you have been given the opportunity to refight it and win. Seize that opportunity like the warriors that you are. Here is what you must do:

“First, the artillery must not fire at the giants this time around. Send officers to all the crews with orders to shoot any man who moves to operate a gun without express command from the general staff.

“Second, move the infantry forward immediately. Press the enemy! Force him to respond! Give him no opportunity to think! He has no idea what has happened. Let that work to our advantage.

“Third, equip the aeroplanes with jellied gasoline bombs. When the giants appear, wait until they are passing through the enemy forces to reach the front. Then have your aviators fly so high the Mongolian Wizard’s forces have nothing that can touch them, and drop the bombs on the giants. The flames will madden the giants with pain and they will trample many of the enemy troops underfoot before they die.

“Fourth, when the dragons appear, wait until they are close enough to be shot down and then command the great guns to fire. Tell the crews that their panic during the last go-around will be forgiven if they keep cool heads and obey the new orders.”

He turned to the Maréchal de France and bowed. “Forgive me for speaking out of turn, sir. I will withdraw now.”

All was done as Ritter had said.

The second time around, the battle went much the way it had originally been expected to. It was hard fought, but superior equipage gave the allies the advantage. Nor could the enemy come up with anything on the fly as cunning as their original strategy. They were forced to retreat and Paris was, for the time being, saved.

“Ritter!” Peter Fischer cried. The sun was going down and the mood in the camp was upbeat. “Look what a general’s cook gave me in exchange for reading his future and telling him that one day he’ll be the most famous chef in Paris.” With a flourish, he produced a roasted leg of lamb. “For your wolf.”

Accepting the meat and kneeling to present it to Freki, who received it with enthusiasm, Ritter remarked, “You’re looking oddly cheerful.”

“I died in combat,” Peter Fischer said, “just as I had foreseen. Now I don’t have to be afraid of being at the front anymore.”

Ritter opened his mouth to explain how very wrong Fischer was, then thought better of it. Let the poor fool keep his delusions for as long as possible. “Your work here is done. As is mine. Gather your kit, and let’s get you back to Covington.”

“Righto!” Fischer said and, with a jaunty wave, strolled off whistling, one of God’s own fools.

Ritter reported to General Garnett, who distractedly dismissed him. He was leaving FHQ when an aide-de-camp came running after him. “There you are! The MaréchaldeFrance commanded me to find out your name.” Lowering his voice in a conspiratorial way, the junior officer added, “He wants to put you in for a medal. The phrasing of the citation will be vague, of course. But the honor will be great.”

Ritter hesitated for only a second. Then he said, “My name is Fischer. Peter Fischer.”

There was a marble bust of Cato the Elder on Sir Toby’s desk, a stuffed owl (Athene noctua) atop his bookshelves, and on the wall a Roman pugio with a dark stain that might plausibly be rust on its blade. The British spymaster received Ritter’s report with every sign of satisfaction. When it was done, Sir Toby began folding up the map of the battlefield and said, “Tell me. What did you make of the MaréchaldeFrance?”

“He is a man of most excellent character, and possessed of every martial virtue save one—he has no imagination. He should never have been promoted so high.”

“So I believe too. And General Garnett?”

“He is not the easiest man to like. But he has courage. When Fischer told him he would die painfully, the general was dismayed. But he did not let it alter his actions. He did his job and died, as was his duty.”

One by one, Sir Toby named the members of the general staff and Ritter gave his impressions. At last, the British spymaster leaned back in his chair. “I’ve been worried about those dragons. Now that we know how to handle them, well, that’s another load off my shoulders.”

“The dragons are not the important part of my report.”

“Oh?”

“No, and you know it,” Ritter said. “Tell me something. Does the experience of this battle mean that we could win the war, suffer one of these time-slippages, and go back to the beginning again, this time possibly to lose? And if it does, could that happen a second time, a third, a tenth? Could it go on forever, over and over, an unending war that can neither be won nor lost?” He felt himself filling with anger. “Is it not possible that we are all condemning ourselves to eternal Hell?”

Sir Toby sighed. “Oh, Ritter. I do wish you wouldn’t ask such questions.”

“Dragons of Paris” copyright © 2024 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2024 by Dave Palumbo

Buy the Book

Dragons of Paris

Very exciting, had me worried there before the ending.

Did the time-slip inventions include valium? I suspect Ritter could do with a few.

Will there eventually be a Mongolian Wizard novel or story anthology in paper form?

I hope so. But I have to write ten more stories first, in order to bring the war to an end. So it’s a little early to be thinking about a collection.

Do you have a plan for when you’ll write these, or more Darger and Surplus?

I have plans for what I’ll write but not when. I’m struggling with a new Mongolian Wizard story at the current moment, but it’s giving me more trouble than usual. It’ll get written, though. My stories always do.

I just discovered these stories and am very much enjoying them. I hope you find the time to continue them and, if you do, look forward to re-reading them in a book.

Wow, I can’t believe I never read any of Swanick’s work before this. What a fantastic story! Looking forward to checking out his other work.