In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

A couple of weeks ago, while rummaging through old books, I came across my old copy of Citizen of the Galaxy. “That was a good one,” I thought. “Perfect for re-reading out in the backyard on a sunny summer day.” I’d first read it back when I was 12 or 13, but didn’t remember many details. It turned out that the book is both more preachy and a lot darker than I had remembered…which made me wonder why so many authors write books for juveniles and young adults that expose the protagonists to so much misery.

While most of Heinlein’s juvenile characters suffer during their adventures, I think poor Thorby is perhaps the protagonist who suffers most. He starts out as a slave, not even remembering his origins. During the brief, happy time that follows his adoption by Baslim the Cripple, the boy is used as an unwitting courier for the undercover intelligence agent. When Baslim is captured, Thorby joins a ship of the Free Traders, a society that wanders the stars but whose individual members have very little freedom. Honoring the wishes of Baslim, he is released to a ship of the Hegemonic Guard, where he enlists in an effort to trigger an investigation of his origins (without having to pay the exorbitant cost of a background check). And as anyone who has served in the military knows, a junior enlistee has very little freedom. When Thorby’s true identity is finally determined, he learns that he is heir to a gigantic fortune—but finds the obligations of his wealth and power to be perhaps the most onerous burden of all. As it turns out, my fond recollections of this book come not so much from its subject matter, but from Heinlein’s writing style, which makes even the darkest and weightiest of subjects interesting and worthy of exploring. And in the end, Heinlein has some positive and thoughtful things to say in this work regarding the duties and responsibilities of being a citizen, and the reader finds that there is some valuable medicine mixed into the spoonful of sugar.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) is among the most notable of science fiction authors, and not surprisingly, I have reviewed his work in this column before. You can find further biographical information in my reviews of Starship Troopers and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. And you will find more information on his series of juvenile novels in my review of Have Spacesuit—Will Travel.

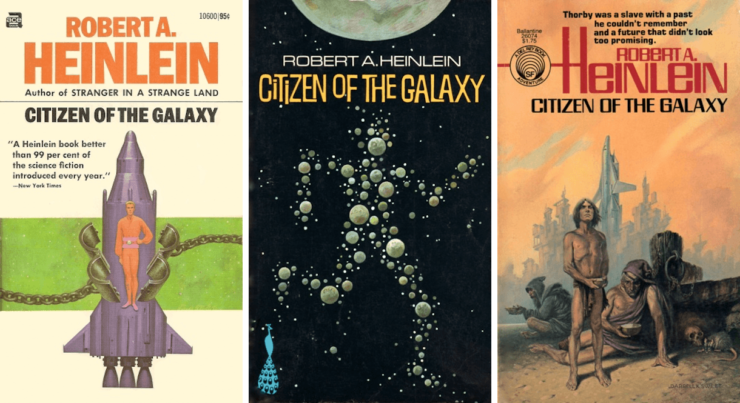

Citizen of the Galaxy was published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1957 as part of their series of Heinlein juvenile adventure novels, and serialized in Astounding Science Fiction in three parts during the same year. In a review on the Heinlein Society website, I found a mention that the two versions were different, with the Scribner’s edition shortened and modified for younger readers.

Citizen of the Galaxy is, at its heart, a rumination on duty and civic responsibility. Readers who are interested in Heinlein’s thoughts on the topic can find more in a Forrestal Lecture he gave to midshipmen at the Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1973. A version of the speech was later printed in Analog, and reprinted in the Heinlein anthology Expanded Universe. The speech is notable in making explicit themes that show up in many of Heinlein’s fictional works. You can find excerpts of it here and there on the internet, but I was not able to find a link to any authorized version. If you can find it, it is worth a look.

Disasters and Dystopias

One might think that books written specifically for young audiences would be a bit gentler than those written for adult audiences. But counterintuitively, the opposite is often true. It seems that the most popular young adult stories are those that put the protagonists in difficult, even extreme, environments and dire straits.

In recent years, dystopias have definitely been in vogue. In Suzanne Collins’ wildly popular Hunger Games trilogy, poor Katniss and her friends are thrown into life-or-death gladiatorial games, and then a full-scale, violent revolution. The Divergent series, by Veronica Roth, takes place in Chicago after an apocalypse, where the inhabitants are divided into warring factions. And the characters in James Dashner’s Maze Runner books find their way through challenging mazes, only to find that the outside world has been destroyed by solar flares. The Harry Potter series is often seen as a whimsical look at a magical world, but starts out with the orphaned Harry living in a closet. While he is rescued by an invitation to Hogwarts, before the series is over, he and his friends will be engulfed in a grueling total war between the forces of good and evil. Back in 2011, Tor.com presented a “Dystopia Week” exploring facets of this subgenre, which featured articles like this one by Scott Westerfeld, and this one by Gwenda Bond.

While young adult dystopias are currently in vogue, they are not new—the subgenre has been around for a long time. A few years ago, Jo Walton wrote a Tor.com article pointing out the dystopic settings found in many of Heinlein’s juveniles, where we encounter wars, disasters and all sorts of grueling rites of passage. And when I look back at some of the books I enjoyed in my youth, they are filled with dire situations and mortal threats. One example that comes to mind is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped, where young David Balfour is betrayed by a relative trying to steal his fortune and then finds himself trapped in the midst of a revolution.

Young adults are at an age where they are looking at what their life will be like when they become independent, which can be a scary prospect. I suspect reading adventures set in dystopias, and seeing the protagonists overcome the intense challenges they face, gives the readers a sense that they, too, can overcome their own obstacles and anxieties. Moreover, seeing how characters react to adversity can teach youngsters some valuable lessons about life and ethical behavior. While older adults might want to shield the young from difficult thoughts and concepts, younger adults are eager to leave the nest and strike out on their own…and fiction can be a first step in doing that.

Citizen of the Galaxy

The book opens in a slave market, with young Thorby being auctioned off to the highest bidder. A powerful customer is insulted by the auctioneer, and when a beggar puts in a low bid for Thorby, the powerful man forces the auctioneer to take the bid. The beggar, Baslim, trains Thorby in his trade but also educated him in languages, math, history, and offers him a life more comfortable than anything the boy has seen since he was captured by slavers. The auction takes place not in the American-influenced Terran Hegemony, but on Sargon, a planet of the Nine Worlds. These worlds are inhabited by a society influenced by cultures of the Middle East, India, and China. As a young reader, I apparently took it for granted that “foreigners” would stoop to evil practices like slavery. But as an older reader, my feelings on the issue are more complex; I feel that Heinlein took the easy way out by putting the practice of slavery into a culture foreign to his American readers. After all, when Heinlein was growing up in Missouri in the early 20th century, there were still people in the region old enough to have been born into slavery, and many of the echoes of slavery still existed in practices like Jim Crow laws. While we are ashamed to admit it, the concept of slavery is not as foreign to our culture as we might like. Putting the problem of slavery into the Terran Hegemony would have added some interesting dimensions to the tale.

Baslim, or Colonel Richard Baslim, turns out to be an intelligence agent from the “X” Corps of the Terran Hegemonic Guard, who volunteered for his current post because of his hatred of slavery. (I was stunned to find, despite Baslim having some past notoriety, he used his own name while undercover; but while that is bad tradecraft, I suspect it was done to make the book easier to follow). While Baslim uses Thorby as a courier, he does his best, through hypnosis and kindness, to help the boy overcome the cruel treatment he had received as a slave. Baslim is a representative of a frequent archetype in Heinlein’s work: the older and wiser mentor who serves as a mouthpiece for the author’s philosophy. Baslim had once done a great service to a people called the “Free Traders,” and gives Thorby information on the ships and captains Thorby should seek out if anything should happen to him. Since he suspects that Thorby had originally come from the Terran Hegemony, he also provides instructions that Thorby be turned over to the first Guard vessel they encountered. In one of the most exciting sequences in the book, Baslim is indeed captured and killed, and Thorby must make his own way through local security forces to the spaceport.

The Free Traders are a collection of families or clans who live on the spaceships they own, tramp freighters that follow business opportunities from star to star. While each ship is as free as an independent nation, keeping those ships functioning forces the individuals aboard them into extremely rigid roles, hemmed in by powerful rules and customs. Because of his math ability, Thorby is trained as a fire control technician, working as part of the ship’s defensive capabilities, and Heinlein does a good job of extrapolating his own naval experience in the 1930s into the future—in fact, those passages have aged surprisingly well in intervening years. Thorby befriends a girl in his watch, and like most Heinlein juvenile heroes, he is utterly clueless about sex and completely misses the fact that she wants to be more than a pal. He is stunned to see her traded off the ship to prevent a violation of mating customs. This section also has a subplot that surprisingly made it past censorious editors, where pin-up magazines are confiscated from the young men on the ship, but then found to be valuable trade goods. This episode in Thorby’s life ends when the captain keeps his promise to Baslim and turns Thorby over to a Terran Hegemonic Guard ship.

Because of Colonel Baslim’s far-reaching reputation, the Guard ship takes Thorby on as a passenger. When their initial efforts to trace his background fail, they talk him into enlisting, which would trigger a deeper, more detailed investigation. Heinlein takes some delight in showing how military personnel can bend rules to accomplish what they need to do. And since military enlistments are basically a form of indentured servitude, Thorby again finds himself in a slave-like role. While he has some run-ins with a messdeck bully, Thorby finds his experiences and Baslim’s training have made him well-suited for naval service. But this service is cut short when Thorby’s actual identity is discovered, and he moves into another phase in what is proving to be a very eventful, episodic life.

It turns out that Thorby is actually Thor Bradley Rudbek of Rudbek (a city that was once Jackson Hole, Wyoming). With his parents dead in the pirate attack that led to his enslavement, he is heir to one of the largest fortunes on Earth. He meets John Weemsby, who wants Thorby to call him “Uncle Jack,” and his “cousin” Leda. After a short period of time, Uncle Jack gives Thorby papers to sign, and when Thorby wants to understand what they say before he signs, Weemsby becomes more and more aggressive in trying to force Thorby’s compliance. On this last reading, Weemsby began to remind me of Tolkien’s character Denethor, the Steward of Gondor, who refuses to accept the rightful king when he returns from a long exile. Thorby also finds that his company has been indirectly supporting the slave trade by selling ships to organizations that support the trade. Thorby decides to challenge Weemsby for control of the company, and fortunately, he has won over Leda, who supports Thorsby’s efforts and introduces him to lawyer James Garsh. Garsh is another of the archetypical characters who appear in more than one Heinlein tale, the feisty and principled lawyer. With the help of Leda and Garsh, Thorby ends up unseating Weemsby and taking control of the company. Thorby approaches the Guard with the information he has discovered about the slave trade, and begins supporting them behind the scenes. While the wealth and power Thorby now wields might be seen as liberating, he actually finds himself feeling more constrained than he has ever been in his life. The book ends on a note that seems incongruous in a story targeted for young readers, with his lawyer telling Thorby he’s working too hard and inviting him out to a restaurant that features dancing girls.

The book is episodic in nature, with each stage of Thorby’s journey, and each difficulty he endures, offering some different perspective on the topics of freedom and responsibility. There are some solid action scenes throughout that keep the reader engaged (and keep the narrative from reading too much like a civics lesson).

Final Thoughts

In researching this article, I noticed that many people count this book among their favorite Heinlein works. It certainly features some of the hallmarks of his best work, and explores many of the themes that he was most passionate about. On the other hand, poor Thorby suffers mightily throughout, the story is clunky at times, and while Heinlein makes the proxy battle at the end as interesting as he can, corporate governance is not the most exciting of topics. I enjoyed the book when I first read it, but having read more of Heinlein, and much more fiction in general since those days, I can’t say that it ranks among my favorites. I do feel, however, that because of the lessons it contains, the book is a good one to offer to young readers.

And now I turn the floor over to you: What are your thoughts on Citizen of the Galaxy? And what do you think about books for young readers that put the protagonists into dystopias and difficult or traumatic situations?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.