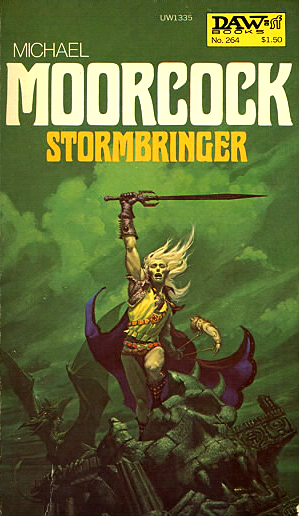

Welcome back to the Elric Reread, in which I revisit one of my all-time favorite fantasy series, Michael Moorcock’s Elric saga. You can find all the posts in the series here. Today we get to the big one: Stormbringer.

Stormbringer is the culmination of Elric’s story, but it’s also one of the earliest-written Elric tales, originally published in four parts in 1964. At the time Science Fantasy, the magazine that had been publishing the Elric stories, was about to fold. So Moorcock decided this would be a good time to “finish the series with a bit of a bang,” as he wrote in 2008, and thus bring Elric’s story to an end—though, of course, he and Elric were far from done with one another.

Now, I’m going to admit to something that I neglected to mention earlier in this reread project. This is actually the first time I’ve read these stories in Elric’s chronological order since I first picked up those Ace paperbacks in my teens. Mind you, I’ve reread all the Elric stories more recently than that—I read each of the Del Rey Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné volumes cover-to-cover as they were published starting in 2008. But that meant reading the stories in the original publication order. Now that I’ve gone back through them all in the Elric order, I do wonder if publication order might not be the better way after all.

Because when you read the stories in Elric order, you’ve had time to lose patience with the Elric-by-numbers stories like those in The Sleeping Sorceress. As well, certain ideas that might otherwise be tantalizingly numinous in Stormbringer have already been visited. For instance, that Elric is but one manifestation of the archetype known as the Eternal Champion, doomed to fight for Law or for Chaos in battle after battle across the Multiverse, has been spelled out in The Sailor on the Seas of Fate and The Sleeping Sorceress. The Cosmic Balance for which Elric unknowingly fights, and of which he sees a vision as he dies, is spoken of much in The Revenge of the Rose and other novels. I wouldn’t go so far as to call Stormbringer anticlimactic—but some of the strangeness seems, well, less strange than it might have been, in light of the seven books that have gone before. But it is, nevertheless, still a solidly-crafted fantasy adventure, and the bleakness of it is still capable of taking your breath away.

Things begin badly in Stormbringer when Elric’s wife is kidnapped from their bed by inhuman creatures working in the service of a dead god. Notwithstanding a few small subsequent victories, there is nowhere for Elric to go from here but down. Ally after ally falls in battle to the forces of the evil sorcerer Jagreen Lern, the catspaw of the gods of Chaos in this plane, and Elric’s own destiny—in the good old Greek tragedy sense, not in the “you have a great destiny” sense that seems to be so popular these days—is finally revealed: he and Stormbringer are the instruments by which his age of the Earth will end. Everything he has ever known—his fallen empire, the Young Kingdoms, the most beautiful things and the most corrupt, all his losses, all his victories, all his friends and enemies and loves—all will be wiped away completely to make way for a new Earth.

Given this, it’s hard to begrudge Elric his self-pity, at last:

So fate makes Elric a martyr that Law might rule the world. It gives him a sword of ugly evil that destroys friends and enemies alike and sucks their soul-stuff out to feed him the strength he needs. It binds me to evil and to Chaos, in order that I may destroy evil and Chaos—but it does not make me some senseless dolt easily convinced and a willing sacrifice. No, it makes me Elric of Melniboné and floods me with a mighty misery…

The audacity of Stormbringer lies not in the plotting, which is straightforward plot-coupon collection, nor in the writing, nor simply in the final death of its anti-hero. This is a book where the “victory” means the complete annihilation of the protagonist and everything he holds dear. It’s not entirely without hope: in a mystical journey that Elric takes to retrieve a magical horn from a hero called Roland, it’s plainly suggested that the demise of Elric’s Earth will give rise to our own. (Medievalists: yes, it’s that Roland.) Still, saving the world by chucking the magic ring in the volcano this is not.

In the first half, we at least have the gratification of watching Elric rescue his wife, getting not one, but two “Did You Just Punch Out Cthulhu?” moments (one with the aforementioned dead god, and one with no less than three Chaos Dukes, including Elric’s own fickle erstwhile patron, Arioch), and a daring escape from Jagreen Lern’s flagship. But once the deaths start piling up in the second half, the grimness becomes absolutely relentless. Not a single Young Kingdom can resist the conquest of Chaos and each is absorbed into its terrifying, seething mass. One character after another falls victim to Stormbringer—a likeable sea-lord, Rackhir the Red Archer, and Elric’s beloved Zarozinia, who flings herself on Stormbringer in despair after having been transformed by Chaos sorcery into a monstrous worm. Even Moonglum must meet his fate on Stormbringer’s point.

Elric soldiers on through all this, having been told by his mystical mentor Sepiriz—who keeps popping up like a jack-in-the-box to tell Elric what he needs to do next—that his miserable journey is all part of his destiny as Fate’s tool in the great battle between Law and Chaos. But it’s a battle where all of Elric’s world loses no matter what—whether Law or Chaos wins, all will be wiped away and forgotten. The question is whether it will be replaced by a “plunging, unsettled world of sorcery and evil hatred” or by a more orderly world, one in which Chaos does not dominate and in which, perhaps, humanity might have a better chance of creating a better world on its own terms.

For someone who has desperately sought meaning for his existence throughout the books, wondering what purpose he serves, it’s a meaning of sorts, but it’s a cold comfort at best—and Elric is left with an answer from Sepiriz that’s not really an answer at all:

“Who can know why the Cosmic Balance exists, why Fate exists and the Lords of the Higher Worlds? Why there must always be a champion to fight such battles? There seems to be an infinity of space and time and possibilities. There may be an infinite number of beings, one above the other, who see the final purpose, though in infinity, there can be no final purpose. Perhaps all is cyclic and this same event will occur again and again until the universe is run down and fades away as the world we knew has faded. Meaning, Elric? Do not seek that, for madness lies in such a course.”

“No meaning, no pattern. Then why have I suffered all this?”

“Perhaps even the gods seek meaning and pattern and this is merely one attempt to find it. Look—” he waved his hands to indicate the newly formed Earth. “All this is fresh and moulded by logic. Perhaps the logic will control the newcomers, perhaps a factor will occur to destroy that logic. The gods experiment, the Cosmic Balance guides the destiny of the Earth, men struggle and credit the gods with knowing why they struggle—but do the gods know?”

Elric is, ultimately, subject to an existential paradox—one which is really a heightened (and rather pessimistic) version of the human condition. His purpose is that of a chess-piece in the struggle between Law and Chaos, but what that purpose means within the larger cosmic scheme is forever a mystery to him, and even to the forces he serves and fights. Law and Chaos in the Moorcock cosmology—something he continues to explore with increasing nuance in future novels—move through history in a constant give-and-take, sweeping up mortals in their currents, and they may or may not be subject to something greater. Elric may as well be acting in the service of a hurricane. And in the end, as dawn rises on the new world for which he has paved the way, he must die as he has lived—by Stormbringer, which drinks his soul and binds him forever to the runeblade-demon which, in its parting words “was a thousand times more evil” than he.

So, we’re done, right?

Well, not really. We’ve actually reached the halfway point in this whole operation. Up next, we’re going to slow down the posting schedule for a couple of cycles. In three weeks, I’ll be back to talk about Zenith the Albino—both the Anthony Skene character who was one of Moorcock’s inspirations for Elric, and Moorcock’s own use of the character in his Metatemporal Detective stories. Then there’ll be another three-week break, and in late November we’ll get back to the biweekly posting schedule with an assortment of Elric short stories, the comic books The Making of a Sorcerer and Michael Moorcock’s Multiverse, and we’ll wrap up in early 2014 with the Moonbeam Roads trilogy. If you’ve stuck with me this far, thank you—and I hope you enjoy the rest of the trip.

Publication Notes:

Stormbringer includes the following four stories:

- “Dead God’s Homecoming,” originally published in Science Fantasy #59 (Nova, June 1963)

- “Black Sword’s Brothers”, originally published in Science Fantasy #61, (Nova, October 1963)

- “Sad Giant’s Shield”, originally published in Science Fantasy #63 (Nova, February 1964)

- “Doomed Lord’s Passing”, originally published in Science Fantasy #64 (Nova, April 1964)

Stormbringer was then published as a single novel in the US and UK. Earlier editions were trimmed for length:

- UK Hardcover, Herbert Jenkins, 1965.

- US Mass Market Paperback, Lancer, 1967.

- Included in Stealer of Souls, vol. 1 of The Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné, Del Rey, 2008. This is the “definitive” edition, per Moorcock’s preferred revisions.

- To be included in the Gollancz collection Stormbringer!, due March 2014.

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.