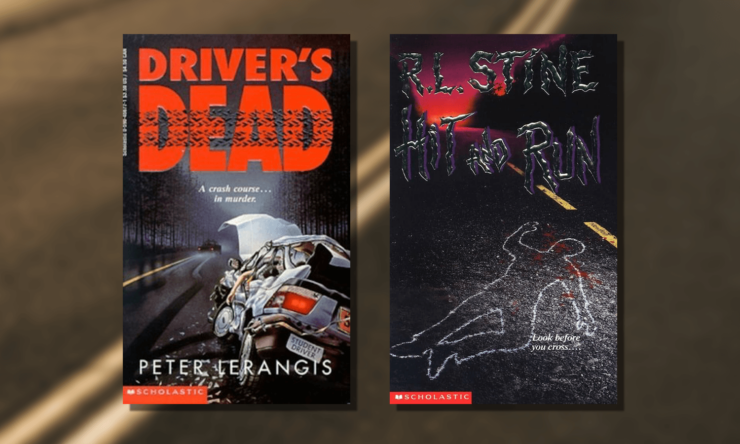

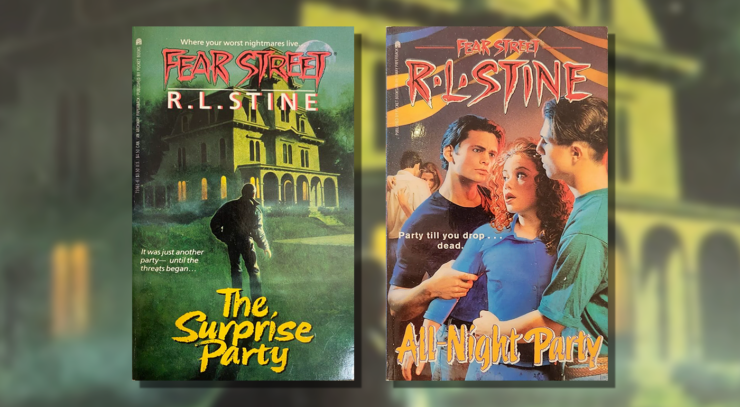

Teen horror is filled with stories of joy rides and road trips gone wrong: there’s the real life danger of R.L. Stine’s The Hitchhiker (1993) and the liminal hallucination of Christopher Pike’s Road to Nowhere (1993). More than one Fear Street party has been centered on getting revenge for fatal car accidents from decades past, with Halloween Party (1990) and The New Year’s Party (1995). Even without ghostly vengeance or rampaging murderers on the loose, however, there is plenty of horror to be had when teens get behind the wheel. They’re new and inexperienced drivers, many of whom are prone to risk taking. They may drive too fast, go places they’re not supposed to go, or take the car out when they don’t have permission. When faced with a crisis, these drivers often don’t have the most logical thought processes, may not have the best judgment, and are likely to make bad decisions based on sheer panic or peer pressure. R.L. Stine’s Hit and Run (1992) and Peter Lerangis’ Driver’s Dead (1994) each take a different approach to exploring these teen driving horrors, from realistic to supernatural.

Stine’s standalone book Hit and Run is realistic and gruesome, with no supernatural scares needed to facilitate the horror. Cassie Martin, Scott Baldwin, Bruce Winkleman (who everyone calls Winks), and Eddie Katz are friends who are all about to get their driver’s licenses. They’ve been friends since they were kids, and while there are some tensions and dramatic intrigue within their friend group—Cassie has a crush on Scott but doesn’t know if he likes her the same way, Eddie is grumpy that everyone’s always pranking him and calling him “Scaredly Katz”—they seem to all get along and take one another’s teasing in good fun. They don’t take anything too seriously, including the things that they probably should. For example, in the book’s opening chapter, Winks shows up at Scott’s house where Scott and Cassie are getting ready to study and says he has a great prank to pull on Eddie, which involves grossing him out with an eyeball in a box. And while most teen horror novels would go with a bait-and-switch gross out (it’s not actually an eyeball, or at least not a human eyeball), Stine is all in. Winks is just wandering around with a real human eyeball that he got from Eddie’s cousin Jerry, who works at the morgue. Cassie and Scott are appropriately horrified about this whole transaction—that Winks would wander into the morgue asking for body parts and that Jerry, apparently, is all too happy to just hand them over—but Winks is dismissive, saying the dead man “was being cremated, so he didn’t need it” (6). Cassie and Scott quickly move past their horror at corpse desecration and Jerry’s lack of professional ethics, and the trio start planning their prank on Eddie, who faints when he sees the eyeball and then gets heckled by his friends for being a wuss.

This is a macabre “what are they capable of?” spot from which to start and it really only gets worse from there. The four teens decide to take Scott’s parents’ car out to practice driving on their own. They drive too fast, goof around, and play hilarious “we’re all going to crash and die” pranks on each other. But despite it all, they make it home safely and don’t get caught, which of course emboldens them to keep sneaking their parents’ cars out so they can practice for their driving tests. This is absolutely a disaster waiting to happen, so it’s not really surprising when one does, and Eddie hits a guy while driving on the dark highway one night. The man—whose ID identifies him as Brandt Tinkers—is clearly dead, the four of them panic, and when Winks says the best thing they can do is flee the scene, it doesn’t take long for the others to agree. Scott argues “he’s right … We don’t have driver’s licenses. The police will fry our butts. Our lives will be ruined. Everyone will know what we did. We could even go to jail or something” (45). Cassie holds on as the empathetic voice of reason for another couple of minutes, but in the end, she concedes as well, reassuring Eddie that “there were no witnesses. What happened is terrible. But it was an accident” (47-8). They didn’t mean to do it and they don’t want to get in trouble, so they decide to just pretend it never happened. Cassie and Scott roll the man’s body off to the side of the road, they all pile back in the car, and they drive away, swearing to take the secret to their graves.

It’s a good thing they have an inside man at the morgue, because when the hit and run doesn’t make the news, they’re able to call Jerry and find out that the body of the man they hit has indeed been brought in … and then mysteriously disappears. They soon start receiving threatening messages and Polaroid pictures of Tinkers’ body sitting in their parents’ cars. Someone mows down Winks in a hit and run accident that he barely survives, followed up by messages that the rest of them are next. Stine gives enough gruesome details about the condition of Tinkers’ body that “maybe he isn’t actually dead” doesn’t hold up as a viable theory, which opens all kinds of doors as readers are briefly left wondering just what kind of horror we’re dealing with. Winks’ eyeball joke really told us all we need to know, though it is still horrifying to discover that Eddie “borrowed” a corpse from the morgue to fake the hit and run and has been driving around with Tinkers’ body in his trunk ever since in order to terrorize his friends. He’s tired of people always making fun of him and since the corpse was that of “some homeless guy” (154), Eddie doesn’t see anything wrong with using this man’s body as part of this disgusting practical joke to turn the tables on his friends and show them “what it’s like to be scared. Really scared” (152).

This is absolutely unconscionable, and one of the most unsettling parts of the whole book is that no one ever actually learns a lesson: Eddie is taken away to get psychiatric treatment and Cassie blames him for the guilt and nightmares she suffered, almost immediately forgetting that they thought they had killed a man and still made the choices they made, and deciding in the aftermath that it doesn’t really matter because it wasn’t really real, so there’s no need for her to take any responsibility or give it another thought. Jerry sneaks in one more prank on Winks, Scott, and Cassie with the dead body before returning it to the morgue and when he leaves it propped up on Winks’ front porch, and Winks pays the joke forward, calling for his parents and telling them “there’s someone at the door who wants to see you!” (164). Cassie, Scott, and Winks don’t learn anything–hey don’t ever come to the realization that they’ve done anything wrong. They don’t make any attempt to find out who Tinkers’ was, how he ended up where he did, or to locate or reunite him with anyone who may be missing him. The man whose corpse has provided them with so much horror and entertainment is completely dehumanized and while readers can hope Tinkers gets respectfully treated and is given a decent burial at some point after these final lines, I don’t know that we can be terribly optimistic.

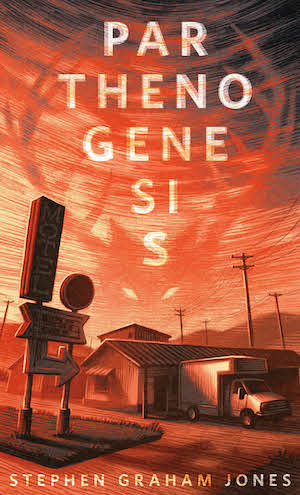

Driver’s Dead has a stronger element of mystery than Hit and Run, as new girl Kirsten Wilkes tries to solve the mystery of a deadly car accident that happened before she moved to town and the dark repercussions that still echo through the community. The commonly accepted story is that Nguyen Trang died by suicide after stealing a car and driving it into a ravine because he was rejected by Gwen, a girl he liked. However, Lerangis immediately reveals the incomplete nature of this narrative in the book’s opening pages with a prologue that captures Nguyen’s final moments, when he went out to meet Rob Maxson and Virgil Garth, two classmates who told him they found a cool car in the woods and who both incidentally have romantic attachments to Gwen. Rob is Gwen’s ex-boyfriend and Virgil likes Gwen, so Rob’s plan is to basically kidnap Nguyen, give him a good scare, and convince him to leave Gwen alone so that Virgil can go out with her. This is far from a foolproof plan, and the car spins out of control on the wet road and plunges over the side. Rob and Virgil somehow survive, Nguyen is killed, and the other two boys have no interest in telling anyone what actually happened, letting the story of Nguyen’s suicide stand.

Like Stine’s Hit and Run, there are plenty of examples in Driver’s Dead of teens making really terrible and dehumanizing choices. Rob and Virgil cover up Nguyen’s death and have no empathy for the suffering of his aunt and uncle, who have raised Nguyen since he was separated from his parents in Vietnam and came to the United States as a refugee. Community members’ perceptions of and memories of Nguyen are overshadowed by their exclusionary thoughts about whether or not he should have been there in the first place, and when Kirsten goes to speak with Olaf, the old man who says he saw Nguyen steal his car, Olaf says “Vietnamese, Japanese, who the hell can tell the difference? ‘Specially at night” (126). When Kirsten asks him follow up questions about exactly what he saw and how he was able well enough at night to identify Nguyen, particularly with his poor eyesight, Olaf gets angry, saying “I know, you’re one of them liberals. Let ‘em all in this country, that’s what you think. Well, see what happened? They think they can get something for nothing! We should force ‘em back to their own country—” (127), before he is interrupted and shushed by his horrified son. Olaf’s statements are the most overtly racist of the responses in Driver’s Dead, but while others won’t say things quite as bluntly as Olaf does, there is a definite sense that Nguyen’s death isn’t all that big of a tragedy because he didn’t really “belong.” The driver’s ed teacher at the high school, Mr. Busk, shares Olaf’s beliefs but is much more covert in expressing them, and Mr. Busk’s sister is a nurse at the local hospital who helps cover up what happened the night Nguyen was killed. Rob and Virgil don’t desecrate Nguyen’s corpse to the extent that Eddie does Brandt Tinkers’ in Hit and Run, but they do manipulate his dead body, shifting him to the driver’s seat following the car accident and letting people construct whatever narrative they see fit, as long as it gets Rob and Virgil off the hook.

While the real-world actions of the humans involved in this accident and its cover up are awful enough, there are also supernatural horrors to contend with, particularly for Kirsten, whose family now lives in the Trangs’ former home. She can sense Nguyen’s unsettled presence in the house and these encounters quickly become terrifying, as she sees blood leaking from underneath her closet door and Nguyen’s burned corpse looming over her bed as he struggles to communicate with her. A car on a contest flier seems to inexplicably move, changing position on the page and threatening to drive right out of the illustration, which Kirsten justifies as her own overactive imagination until Rob is run over and she finds a car-less flier near his body. Lerangis suggests that Nguyen has telekinetic abilities in the prologue section, when a photograph of Gwen moves before Nguyen heads out for his ill-fated meeting with Rob and Virgil, adding another layer of supernatural power to the equation. Nguyen was a real car guy and between that passion and his desire to see those who murdered him pay, this car flier is oddly effective, if difficult to define, with a panicked Virgil asking the big questions like whether the power can be “activated if the flyer’s inside an envelope” (198) and “If we’re in a car, can another car materialize inside it? (199, emphasis original). Nguyen is clearly trying to communicate something from beyond the grave and when Kirsten finds his diary on a floppy disk hidden behind some paneling in her bedroom wall, she’s one step closer to solving the mystery.

When Kirsten figures it out, there’s plenty of blame to go around, with several people either conspiring in the cover up or remaining complicit: Rob was driving the car when it went off the road, though the accident was at least partially due to Mr. Busk, who was driving drunk and met Rob’s car coming from the other direction. Rob, Virgil, and Mr. Busk work together to make it look like Nguyen was driving. Mr. Busk’s sister falsifies hospital records when the three of them come in to have their injuries treated. Gwen wasn’t that into Nguyen and was only seeing him to try to make Rob jealous, but she did accept his gift of a family heirloom locket with photographs of his parents inside it. (Of all of these people, Gwen’s true feelings remain the most elusive: while Nguyen doesn’t seem to have meant all that much to her, she keeps wearing the locket after he dies. Then, either worried about being seen with it–or having had a few unpleasant encounters of her own with Nguyen’s unhappy ghost, she takes it to the pawn shop with all the other gifts he had given her).

Kirsten determines that Nguyen’s spirit has two desires: to reclaim the locket he gave to Gwen, and to have people know the truth about what happened the night he was killed. Kirsten is a terrible driver, and driving ends up being at the center of a lot of the conflicts and confrontations throughout the book: Mr. Busk is her driver’s ed teacher and is (unsurprisingly) a real jerk. When she pulls the driver’s ed car back into its spot in the school parking lot at the end of class one day, Rob pretends she hit him with the car and falls to the ground “dead.” Rob gives Kirsten driving lessons and is actually a really good teacher, though he also uses this opportunity to get her alone and force himself on her. He talks her into taking a walk in the dark park—a reputed makeout spot—and then pushes her down on a park bench and kisses her. When Kirsten bites Rob to get away from him, he is furious, telling her “I was doing what you wanted … I sat here, and what did you do? You didn’t keep walking. You sat next to me” (57, emphasis original), conveniently forgetting that she suggested they start walking back to the car before he invited her to sit next to him, with a manipulative “Okay, if you don’t trust me” (52) when she hesitated. Kirsten is equally furious and storms off to walk home alone. Unfortunately, she does doubt herself, wondering “Had she been too severe? Too judgemental? Too violent?” (58), but in the end she keeps walking and doesn’t go back. The next she sees of him, his dead body is being loaded into an ambulance when she gets to school in the morning—and Gwen is threatening to tell the police Kirsten killed him, because Gwen found Kirsten’s keys by Rob’s body. When Mr. Busk realizes that Kirsten is on to the truth, he traps her in a car and sets her up to get hit by a train, though she is able to break out one of the windows and scramble to safety moments before the impact. Kirsten’s driving experiences are an unruly combination of good, bad, and ugly, and when she sets out to reclaim the locket and reveal the truth, she does so by driving recklessly through town without a license and in a stolen car. She breaks the window of the pawn shop with the car’s anti-theft Club, takes the locket, and returns to the scene of the accident, where Nguyen’s aunt and uncle later scattered his ashes, to reunite the young man with this symbolic connection to his parents. There she has an encounter with Nguyen’s spirit, as a whirling vortex of dust becomes “recognizable now. It had taken on a human form—head, torso, arms, legs—all composed of swirling ashes” (212), which reaches out and reclaims the locket before “a flash of light obliterated everything around her, and she fell to the ground” (212). In the end, comeuppances are fairly roundly distributed for those who were there the night of the accident: Rob and Mr. Busk are killed by the supernaturally rampaging car from the flier and Virgil, whose actions the night of Nguyen’s death were passive and complacent, though still misguided, has made amends by helping Kirsten clear Nguyen’s name and lay his spirit to rest.

In both Hit and Run and Driver’s Dead, teens behind the wheel make some terrible choices, endangering the lives of themselves and others. But the real horror comes from their dehumanization of people who are different from them, people who they decide don’t really “count” in the same way that they themselves do. In Hit and Run, Eddie doesn’t see anything wrong with his use and abuse of Tinkers’ corpse because Tinkers was homeless and his body remained unclaimed, with no one to advocate for him or ensure his body is treated with dignity and respect. In Driver’s Dead, racism, xenophobia, and exclusion set Nguyen and his family apart from their larger community, isolating them both in their lived experiences and in their grief following Nguyen’s death, when the people who killed him are able to construct their own self-serving story, knowing that no one will care enough about Nguyen to question it. From the real to the supernatural, there’s plenty of horror to go around, and in both books, it all falls on those whose otherness seems to make them expendable to those who exploit them.