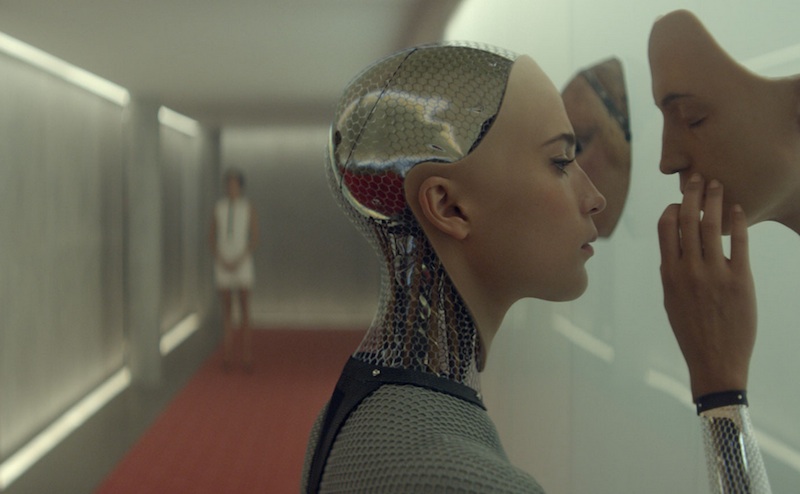

Early on in Alex Garland’s tense, darkly funny, sci-fi psychological thriller Ex Machina, coder Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) keenly points out that he hasn’t actually been summoned to his boss Nathan’s (Oscar Isaac) secluded mountain home to perform a Turing test. The basis of that test, you see, is that the examiner does not know that the subject is actually a machine. In this case, Nathan’s android prototype Ava (Alicia Vikander) is clearly inhuman, with her face and hands covered in synthetic skin but her insides laid bare in a mix of metal mesh and fiberglass components. Nathan’s aim is not to deceive Caleb as to Ava’s true form.

This is the only honest moment in the movie. The rest of this taut cautionary tale has the characters and the audience constantly sifting through layers of trickery and manipulation—from both humans and machines. The growing dread we share with Caleb is tempered by sweet, witty, and truly “wtf” moments, little pockets of humanity that only serve to further convince us that everyone is human… or everyone is a machine… or both. While Ex Machina isn’t perfect, as Garland’s directorial debut, it’s incredibly polished.

With each of the movies he’s written, Garland has pushed the conventions of that genre a step beyond what’s been explored before. In Sunshine, the mission to reignite the sun is a backdrop for depicting the psychological breakdown of the two ships’ crew members. 28 Days Later begins not with the first wave of zombie infection, but with the infection raging for a month when the protagonist awakens from his coma. (This was a year before Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead would open on a similar visual.) Ex Machina is no different, in that it changes the Turing test itself. Caleb’s challenge lies in interacting with Ava—literally staring into her depths—and still locating that spark of consciousness, that proof.

But Garland is the man who turned a space mission into a slasher flick halfway through, so don’t expect Ex Machina to be just about a Turing test. The irony is not lost on us that this machine—who is aspiring to be “the whole package” of a fully functional creature—is being judged by two humans who are broken in different ways. A tragedy in his youth has hardened Caleb, so that even his most nervous, pleasant smiles exist beneath a thin, hardened shell. Thrust into the lap of luxury—but also secrets concealed by menacingly matter-of-fact security—he’s guarded around everyone with whom he interacts.

Then there’s genius inventor Nathan, a literal functioning alcoholic who has to award employees with free retreats in order to get someone to hang out with him. And they certainly shoot the shit, in almost-comedic sequences of alpha and beta male bro-bonding. Some scenes play like a reverse-failed Bechdel test, where Nathan and Caleb fawn over Ava (from “She’s pretty fucking awesome!” to “Do you think she’s programmed to like you?”) over beers and vodka. She’s all they talk about.

The question of Ava’s artificial intelligence is very quickly established and dismissed. It’s clear from the start that Nathan has made an unprecedented leap forward into establishing humans as both gods and fossils. (His eagerness to be crowned a deity coupled with his resignation that he has brought about his mankind’s obsolescence is perhaps the best way to sum up his character’s self-sabotaging nature.)

The real question is, what happens next—once everyone is on the same page about Ava’s AI, how does that change Caleb’s reactions to her and her own aspirations? From their first session, they are mutually charmed; they could be two strangers meeting-cute at a coffee shop. When Caleb raises his misgivings about Ava clearly imprinting on him, Nathan shrugs it off with a simple explanation: I programmed her to be heterosexual. You’re the first man she’s met aside from me, and I’m like her dad.

Vikander plays Ava with a mix of naiveté and world-weariness; she wholeheartedly embraces her attraction to Caleb like a child with her first, unfettered crush, but also like a woman more confident than the man she’s pursuing. When she shyly shows him a more human side of herself—a scene that is sexually charged even as she’s adding layers of clothing—every movement is precisely timed to his corresponding biological response.

Ava embodies sexuality, but at a distance. It’s all flirtation without any follow-through—even though Nathan seems far too confident that all of her parts function well for that sort of encounter. Yet where I saw a heady atmosphere of unresolved sexual tension, The Guardian perceived a more controlled, almost experimental environment:

Yet at its heart is an ironic absence of sexuality, a detachment from desire similar to that exhibited in Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, in which Scarlett Johansson’s predatory alien inhabits the form of an alluring young woman in order to prey, Species-style, upon unsuspecting humans. Just as Blade Runner wondered whether its lifelike replicants could really fall in love, so Ex Machina spirals obsessively around the question not of artificial intelligence but artificial affection, worrying away at the authenticity of attraction as an indicator of consciousness itself.

That said, I completely agree with their evaluation of artificial intelligence versus affection. The above review also makes a keen comparison between Ex Machina and 2013’s Her, as in both a human man knowingly falls for a machine in spite of the complications of that situation. But when Theodore and Samantha organically fell in love, there was never any question that she was manipulating him, because she didn’t gain anything by doing so. For all that Samantha could travel to other planes of consciousness and interact with other OSes, Ava is a lab rat, confined to her room by her overprotective father.

The nagging fear that someone doesn’t really like you—what could be a more human demonstration of emotions! Caleb’s sessions with Ava are enough of a mindfuck that he begins questioning what—or who—is real and what’s not. The credit for bringing Ava almost entirely out of the uncanny valley goes to both comic book artist Jock (who contributed initial character sketches) and the visual effects house of Double Negative. The latter worked with Garland to develop “wetware” (his coined term) to make Ava look organic even when you were staring at her wires and circuits, and to couple her most human gestures with faint, gyroscopic tics that remind Caleb and us that she’s still a machine.

These constant, intersecting identity crises—machines who look like humans, humans who look like machines—creates the kind of paranoia that hearkens back to Battlestar Galactica’s Cylons. (It also extends outward to search engines and social media in ways I won’t spoil.) And for what it’s worth, there’s an incredible disco dance sequence (set to Oliver Cheatham’s “Get Down Saturday Night”) that’s so synchronized you have to wonder if one or more of the participants are well-oiled machines.

Because the most convincing lies grow around a kernel of truth, you’re never able to know who’s telling the truth. Upon watching the first few trailers, I was sure I would know the movie’s twist going in. Instead, it got me asking other questions.

Must all “authentic” (in the sense of mimicking human intelligence) interactions be characterized by deception and/or paranoia? Is duplicity the key to proving humanity?

Ex Machina won’t give you a straight answer, just a series of anecdotes involving lonely people looking for connection—and reaping the consequences when they make contact.

Natalie Zutter wants to learn Oscar Isaac’s disco dance routine. You can read more of her work on Twitter and elsewhere.

Really want to get out and see this one!

Was this a limited theatrical release or something? It says it came out today but I don’t see any listings near me. Boo :(

@2: It seems like it’s been out since at least SXSW, if not earlier. I think it got released in NY/LA today; other theaters might get it in a few weeks?

This came out in january in the uk. Anyone who hasn’t seen it needs to drop everything and do so; a really mesmerising piece of work. You kinda think you know where it’s heading going in but it really does have many WTF moments – the dance being one of the funniest but utterly creepiest scenes i’ve watched in a while.

I want more on-screen sci-fi like this, please. Something to get the old wetware working, it lingers long after you’ve seen it.

@@.-@

That is EXACTLY what I expect from good scifi but is unfortunately often lacking these days. I will definitely check this one out.

I had never heard of Alicia Vikander before last Christmas or thereabouts, and then in short order saw her in both Ex_Machina (I’m in the UK, where it has been out for ages) and Testament of Youth – both rather different movies. One to watch for the future, I think.