Holy work sometimes requires unholy deeds…

Join us every Monday in April for an extended preview of The Devils, a brand-new epic fantasy from author Joe Abercrombie featuring a notorious band of anti-heroes on a delightfully bloody and raucous journey. The Devils publishes May 13, 2025 with Tor Books. Get started with chapters 1 through 3 below!

Brother Diaz has been summoned to the Sacred City, where he is certain a commendation and grand holy assignment awaits him. But his new flock is made up of unrepentant murderers, practitioners of ghastly magic, and outright monsters. The mission he is tasked with will require bloody measures from them all in order to achieve its righteous ends.

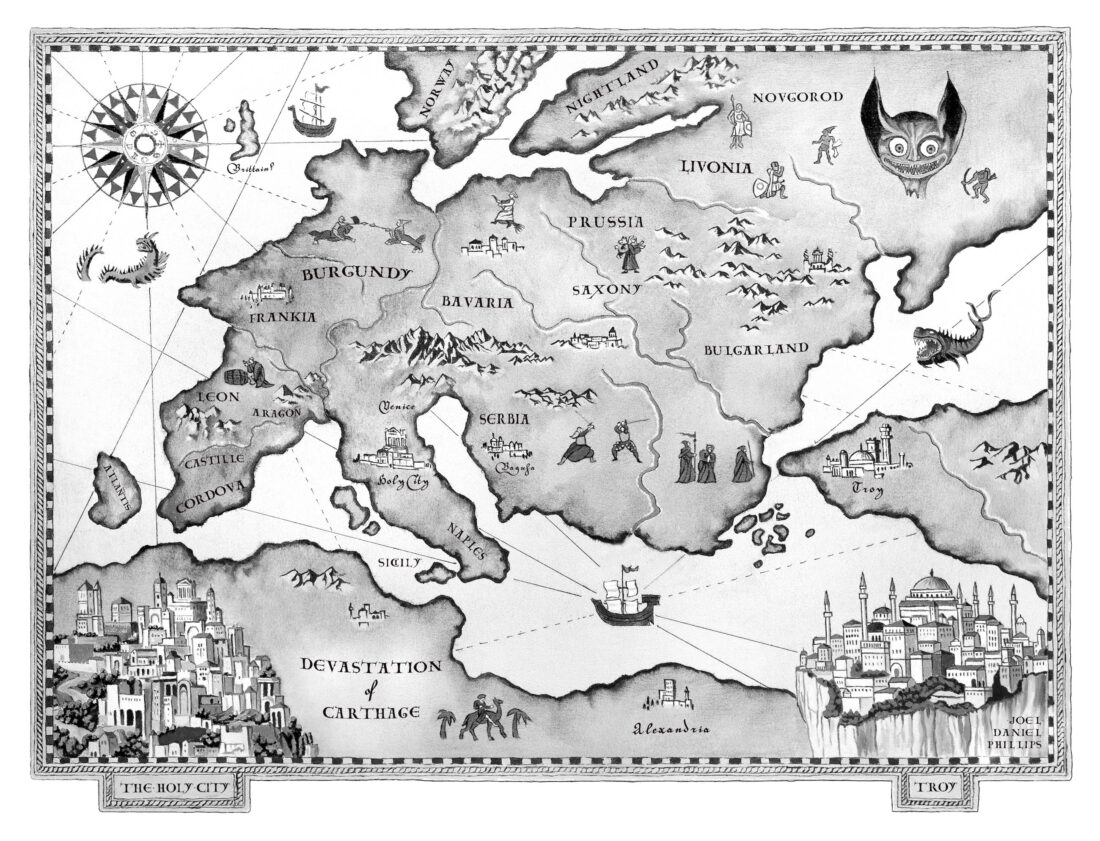

Elves lurk at our borders and hunger for our flesh, while greedy princes care for nothing but their own ambitions and comfort. With a hellish journey before him, it’s a good thing Brother Diaz has the devils on his side.

Part I: Worst Princess Ever

Chapter 1

Saint Aelfric’s Day

It was the fifteenth of Loyalty, and Brother Diaz was late for his audience with Her Holiness the Pope.

“God damn it,” he fretted as his scarcely moving carriage was buffeted by a procession of wailing flagellants, their backs streaked with blood and their faces with tears of rapture, whipping themselves along beneath a banner that read simply, “Repent.” What one was called upon to repent of wasn’t specified.

Everyone’s got something, don’t they?

“God damn it.” It might not have been numbered among the Twelve Virtues, but Brother Diaz had always prided himself on his punctuality. He’d allowed a full five hours to get from his hostelry to his interview, sure that would leave him with at least two to piously admire the statues of the senior saints before the Celestial Palace. It was said all roads in the Holy City led there, after all.

Only now it seemed all roads in the Holy City led around and around in chilly circles crawling with an unimaginable density of pilgrims, prostitutes, dreamers, schemers, relic-buyers, indulgence-dealers, miracle-seekers, preachers and fanatics, tricksters and swindlers, prostitutes, thieves, merchants and moneylenders, soldiers and thugs, an astonishing quantity of livestock on the hoof, cripples, prostitutes, crippled prostitutes, had he mentioned the prostitutes? They outnumbered the priests some twenty to one. Their glaring presence at the blessed heart of the Church, screeching smoking come-ons and displaying goosefleshed extremities to the uncaring cold, was shocking, of course, disgraceful, undoubtedly, but also stirred desires Brother Diaz had hoped long buried. He was obliged to adjust his habit and turn his eyes heavenwards. Or at any rate towards the jolting ceiling of his carriage.

That sort of thing was what had got him in trouble in the first place.

“God damn it!” He dragged down the window and stuck his head into the frosty air. The cacophony of hymns and solicitation, of barter and pleas for forgiveness—and the stench of woodsmoke, cheap incense, and a nearby fish market—were both instantly tripled, leaving him unsure whether to cover his ears or his nose while he screamed at the driver. “I’m going to be late!”

“Wouldn’t surprise me.” The man spoke with weary resignation, as though a disinterested bystander and not charging an exorbitant fee to convey Brother Diaz to the most important appointment of his life. “It’s Saint Aelfric’s Day, Brother.”

“And?”

“His relics have been hoisted up the steeple of the Church of the Immaculate Appeasement and displayed to the needy. They’re said to cure the gout.”

That explained all the limps, canes, and wheeled chairs in the crowds. Couldn’t it have been scrofula, or persistent hiccups, or some malady that left the afflicted capable of flinging themselves out of the path of a speeding carriage?

“Is there no other route?” Brother Diaz screeched over the gabble.

“Hundreds.” The driver directed a limp shrug at the swarming crowds. “But it’s Saint Aelfric’s Day everywhere.”

The bells for midday prayers were starting to echo over the city, beginning with a desultory dingle or two from the roadside shrines, mounting to a discordant clangour as each chapel, church, and cathedral added its own frantic peals, jockeying to hook the pilgrims through their doors, onto their pews, and up to their collection plates.

The carriage lurched on, flooding Brother Diaz with relief, then immediately lurched to a halt, plunging him into despair. Not far away two ragged priests from competing beggar-orders had been cranked up in telescopic pulpits, swaying perilously above the crowd with a groaning of tortured machinery, spraying spit as they argued viciously over the exact meaning of the Saviour’s exhortation to civility.

“God damn it!” All that work undermining his brothers at the monastery. All that trouble preventing the abbot’s mistresses from finding out about each other. All his bragging about being summoned to the Holy City, singled out as special, marked for a great future.

And this was where his ambitions would die. Buried in a carriage stalled in human mire, in a narrow square named after a saint no one had heard of, cold as an icehouse, busy as a slaughterhouse, and squalid as a shithouse, between a painted enclosure crammed with licensed beggars and a linden-wood platform for public punishments, on which a set of children were burning elves in straw-stuffed effigy.

Brother Diaz watched them beating the pointy-eared, pointy-toothed dummies, sending up showers of sparks while onlookers indulgently applauded. Elves were elves, of course, and surely better burned than not, but there was something troubling in those chubby little children’s faces, shining with violent glee. Theology had never really been his strong suit, but he was reasonably sure the Saviour had talked a lot about mercy.

Thrift most definitely was numbered among the Twelve Virtues. Brother Diaz always reminded himself of that as he gave the beggars outside the monastery gates a wide berth. But sometimes one has to invest to turn a profit. He leaned out of the window to scream at the driver again. “Promise to get me to the Celestial Palace on time and I’ll pay double!”

“It’s the Holy City, Brother.” The driver barely even bothered to shrug. “Only madmen make promises here.”

Brother Diaz ducked back inside, tears stinging his eyes. He squirmed from his seat onto one knee, slipped out the vial he wore around his neck, its antique silver polished by centuries against the skin of his forebears. “O Blessed Saint Beatrix,” he murmured, gripping it desperately, “holy martyr and guardian of our Saviour’s sandal, I ask for only this—get me to my shitting audience with the Pope on time!”

He regretted swearing in a prayer at once and made the sign of the circle over his chest, but while he was working his way up to pinching himself in the centre by way of penance, Saint Beatrix made her displeasure known.

There was an almighty thud on the roof, the carriage jolted, and Brother Diaz was flung violently forward, his despairing squawk cut short as the seat in front struck him right in the mouth.

Chapter 2

How It Goes

Alex nailed the jump from window to carriage-roof, rolled smooth as butter and came up sweet as honey, but botched the much easier jump from carriage-roof to ground, twisted her ankle, blundered off balance through the crowd, bounced mouth-first from the dung-crusted flank of a donkey, and went sprawling in the gutter.

The donkey was quite put out and its owner even more so. Alex couldn’t be sure what he was yelling over the wails of some passing penitents, but it was not flattering.

“Fuck yourself!” she screamed at him. A monk gawped at her from the carriage, with a bloody mouth and that look of sweaty panic tourists get in the Holy City, so she shrieked, “And you can fuck yourself, too! Fuck each other,” she added, half-hearted as she hobbled away.

Swearing’s free, after all.

She whipped a prayer-cloth from a stall while the merchant wasn’t looking—which wasn’t so much theft in her book as just good reflexes— wrapped it over her head scarf-like, and slipped among the penitents, doing her best pitiful moan. Not difficult given the pain throbbing up her leg and the prickle of danger tickling her neck. She raised her hands towards the jagged strip of blue between the mismatched roofs and mouthed a smoking prayer for deliverance. For once, she almost meant it.

This is how it goes. Start the evening looking for fun, end the morning begging forgiveness.

God, she felt sick. Stomach churning, burning up her sore throat, and there was the rumour of trouble at her arse-end, too. Maybe last night’s bad meat or this morning’s bad prospects. Maybe the money she’d lost or the money she owed. Maybe a little dung on the lips, still. Then the unholy stench of the pilgrims—forbidden from washing on their long treks to the Holy City—wasn’t helping anyone. She twitched a corner of the prayer-cloth over her mouth and stole a glance backwards, peering through the thicket of arms raised to heaven—

“There she is!”

No matter how she tried, she never could quite fit in. She elbowed past a blindfolded pilgrim, shoved over another shuffling on his scabbed knees, and lurched up the street as quick as she could with a bad ankle, which was nowhere near as fast as she’d have liked. Over the noise of someone belting out hymns for coppers she could hear chaos behind. A fight, if she was lucky, those penitents could get pretty frisky if you came between them and the grace of the Almighty.

She skittered around a corner into the fish market in the shadow of the Pale Sisters. A hundred stalls, a thousand customers, the clamour of bad-tempered barter, the salty sea-reek of the morning’s catch, gleaming in the watery winter sunlight.

She glimpsed a flash of movement and dropped on a reflex. A clutching hand ripped a loose hair from her head as she went sliding under a wagon, was almost clubbed by pawing hooves, rolled away to wriggle between someone’s legs, through the chilly slather of guts and bones and slimes beneath the stalls.

“Fucking got you!”

A hand clamped around her ankle, her fingernails leaving worming trails through the fish mulch as she was dragged into the light. It was one of Bostro’s thugs, the one suffering from a three-cornered hat made him look like a failed pirate. She came up punching, landed one on his cheek with a sick crunch that she’d a worry was her hand not his face, and he caught her wrist and wrenched her sideways. She spat in his eye, made him flinch, booted him in the groin and made him stumble, flailing about with her free hand. They might put her down, but she’d never stay down. Her fingers found something and she shrieked as she swung it. A heavy pan. It smashed the pirate across the cheek with a sound like the bells for evening prayers, knocked his stupid hat spinning, and laid him out lengthways, customers diving away as hot oil showered everywhere.

Alex spun around, a fishy wad of her own hair stuck across her eyes. Staring faces, pointing fingers, figures forcing through the crowd towards her. She sprang onto the nearest stall, planks bouncing on their trestles as she kicked through the ocean’s bounty, fish flopping, crabs crunching, merchants roaring abuse. She sprang for the next stall, slipped on a huge trout, and reeled one more desperate step before she crashed down on her shoulder and went sprawling in a shower of shellfish. She struggled up gasping, limped for a rubbish-choked alleyway, and was about four steps down it before she saw it was a dead end.

She stood there in a horrified crouch, staring at the blank wall with her hands helplessly opening and closing. Ever so slowly, she turned.

Bostro stood in the mouth of the alley, big fists propped on hips, big jaw jutting, a blank slab of menace. He clicked his tongue with a slow tut, tut, tut.

One of his thugs joined him, breathing hard from the chase. The one with the grin full of brown teeth. God, they were a sight. If you had that grin, at least clean your teeth, and if you had those teeth, at least don’t grin.

“Bostro!” Alex produced the best smile she could while panting for breath, which was a poor one, even by her standards. “Didn’t know it was you.”

His sigh was as weighty as the rest of him. He’d been collecting for Papa Collini for years and must’ve heard every trick, lie, excuse, and sob story you could imagine and no doubt quite a few you couldn’t. This one didn’t impress him.

“Time’s up, Alex,” he said. “Papa wants his money.”

“Fair enough.” She held out her bulging purse. “Here’s the whole sum.”

She tossed it to him then made a dash for it, but they were ready. Bostro caught the purse while his shit-toothed friend caught Alex by the arm, swung her around, and flung her against the wall so her head smacked the bricks and she went rolling in the rubbish.

Bostro opened the purse and eyed the contents. “Here’s a shock.” He dangled it upside down and dirt showered out. “Your purse is as full of shit as you are.”

The aspiring pirate had joined the party with a pink pan-mark down his face. “Watch it,” he grunted, knocking a dent from his fish-smeared hat. “She’s vicious when cornered. Like a starving weasel.”

She’d been called worse. “Now look,” she croaked as she clambered up, wondering if they’d broken her shoulder, then when she tried clutching at it wondering if she’d broken her hand. “I’ll get him the money. I can get him the money!”

“How?” asked Bostro.

She pulled the rag from her pocket and unfolded it with suitable reverence. “Behold the fingerbones of Saint Lucius—”

The one with the hat slapped them out of her hand. “We know dog feet when we see ’em, you swindling bitch.” Which was quite upsetting after all the work she’d put into filing the claws down.

“Now look,” she said, backing away with her battered, throbbing, fishy hands up but fast running out of the alley, “I just need a bit more time!”

“Papa gave you more time,” said Bostro, herding her backwards. “It ran out.”

“It’s not even my debt!” she whined, which was true, but entirely beside the point.

“Papa warned you not to take it on, didn’t he? But you took it on.” Which was also true, and very much on the point.

“I’m good for it!” Her voice was getting higher and higher. “You can trust me!”

“You’re not and I can’t, and we both know it.”

“I’ll go to a friend!”

“You don’t have any.”

“I’ll find a way. I always find a way!”

“You haven’t found a way. That’s why we’re here. Hold her.”

She landed a punch on Shitty Teeth with her good hand, but he barely noticed. He caught her arm and the pirate caught the other, and she kicked and twisted and wailed for help like a mugged nun. They might put her down, but she’d never stay—

Bostro thumped her in the stomach.

It made a thud like a stable boy dropping a damp saddle and the fight fell straight out of her. Her eyes went wet and her knees went floppy and all she could do was hang there and make a great long vomity wheeze and think actually it might be best if she stayed down after all.

There really is nothing romantic about a punch in the gut from someone twice your size, specially when the best you’ve got to look forward to is another. Bostro caught her around the throat with one great fist and cut her wheeze off to a slippery gurgle. Then he took his pincers out.

Iron pincers. Polished from lots of use.

He didn’t look happy about it, but he still did it.

“Which’ll it be?” he grunted. “Teeth or fingers?”

“Now look,” she slobbered, near swallowing her tongue. How long had she been playing for time? A week or two more. An hour or two more. She was down to playing for moments. “Now look—”

“Pick,” snarled Bostro, his pincers getting so close to Alex’s face she went cross-eyed staring at them, “or you know it’s both—”

“One moment!” The voice rang out, sharp and commanding, and everyone looked around at once. Bostro, the thugs, and Alex, too, far as she could while half-throttled.

A tall, handsome man stood in the mouth of the alley. In her line of work, you learn to tell how rich someone is at a glance. Tell who’s rich enough to be worth swindling. Tell who’s too rich to be worth the trouble. This was a very rich one, robe worn around the hems, but good silk, stitched with dragons in golden thread.

“I am Duke Michael of Nicaea.” He had a trace of an eastern accent, it was true. A bald fellow with sweat on his forehead hurried up beside him. “And this is my servant Eusebius.”

Everyone took stock of this surprising turn-up. The so-called duke was looking at Alex. He had a kind face, she thought, but then she could put on a very kind face and she was a thieving bitch, ask anyone. “I understand your name is Alex?”

“You understand correctly,” grunted Bostro.

“And do you have a birthmark beneath your ear?”

Bostro shifted his thumb and raised his brows at the piece of neck revealed. “She does.”

“By all the saints…” Duke Michael closed his eyes and took a very deep breath. When he opened them, it looked like there might be tears there. “You’re alive.”

Bostro’s grip had loosened enough for Alex to wheeze, “For now.” She was shocked as anyone, but the winners are those who get over their shock quickest and start working out where the profit is.

“Gentlemen!” announced the duke. “This is none other than Her Highness the Princess Alexia Pyrogennetos, long-lost daughter of the Empress Irene and rightful heir to the Serpent Throne of Troy.”

Bostro must’ve heard every trick, lie, excuse, and sob story you could imagine, but this one lifted even his eyebrows. He squinted at Alex as if someone had told him the turd he’d just watched squeezed from a goat’s arse was actually a gold nugget.

All she could do was shrug her shoulders very high. She’d been called a scammer, a fleecer, a cheat, a thief, a bitch, a thieving bitch, a ferrety fuck, a lying weasel, and those were only the ones she’d taken as compliments. She’d never, far as she could remember, been called a princess. Not even in the least funny jest.

Shitty Teeth’s face twisted so violently that even shittier teeth came into view towards the back. “She’s fucking what now?”

Duke Michael considered Alex, hanging there like a cheap rug halfway through its annual beating. “I will admit she does not appear… terribly princessy. But she is what she is and we’ll all have to live with it. I must therefore insist that you unhand her royal person.”

“Unhand?” asked the would-be pirate.

“Let go of her.” The duke’s pleasant manner peeled back a touch and Alex caught a glimpse of something flinty underneath. “Now.”

Bostro frowned. “Lying weasel owes our boss.”

The pirate twisted a tooth from his bloody mouth. “Ferrety fuck knocked out one o’ my teeth!”

“Shame.” The duke raised his brows at the tooth. “It looks a really good one.”

The man angrily tossed it away. “Well, I bloody liked it.”

“I see you have suffered some inconvenience.” Duke Michael reached into a pocket of his gold-threaded robe. “God knows, I am well aware how inconvenient princesses can be, so…” He held some coins up to the light. “Here is something…” He put a couple back, then tossed the rest onto the dirty cobbles. “For your trouble.”

Bostro peered down, scarcely more impressed than he had been by the dirt in Alex’s purse. “Thought she was a fucking princess?”

“When announced by a herald it is typically without the fucking, but yes.”

“And that’s what her life’s worth?”

“Oh, no,” said Duke Michael. His servant sank gracefully to one knee beside him, pulled open his coat, and produced a large sword, its stained sheath chased with shining wire, its battered gold pommel tilted towards his master. The duke rested one fingertip upon it. “That’s what your lives are worth.”

Chapter 3

The Thirteenth Virtue

I… am…”

Brother Diaz let fall the hem of his habit, which he’d been obliged to gather up around his knees like a flustered bride arriving late to her wedding, his flapping footfalls echoing from mirror-polished marble as he scurried around the labyrinthine hallways of the Celestial Palace in ever greater extremes of sweaty panic.

“I… am…” He’d slipped on a patch of fresh saliva where a party of high-ranking penitents were licking the floor clean and thought he might have done himself a mischief around the groin area. It was all a very long way from the towering dignity with which he’d dreamed of sweeping through these hallowed halls to finally have his quality acknowledged. God, his head was spinning. Was he fainting? Was he dying?

“Brother Eduardo Diaz?” asked the immensely tall secretary.

The name sounded familiar. “I think so…” He leaned on the desk with both fists, struggling to control his wheezing and appear worthy of a respectable post in the middle of the Church’s hierarchy. “And I can only… apologise… for being late.” He managed, with a heroic effort, to prevent himself from vomiting. “There was a damned gouty crowd out for Saint Aelfric’s Day! And the driver—”

“You are early.”

“—was no help whatsoever, and I—What?”

The secretary shrugged. “It’s the Holy City, Brother Diaz. Every day is at least one saint’s day, and everyone is always late. We shift all the appointments to allow for it.”

Diaz sagged with relief. Sweet Saint Beatrix had come through for him after all! He might have dropped to his knees to weep his thanks on the spot, had he not feared he would never rise again.

“But never fear.” The secretary clambered down from what must have been a very high stool and revealed herself to be surprisingly short. “Cardinal Zizka has cleared her schedule and asked that you be shown in the moment you arrived.” And she gestured to a door with a showman’s flourish.

A large man, craggy-faced and crooked-knuckled, sat on a bench beside it, perhaps awaiting his own interview. He sat with his grey eyes on Brother Diaz, in such perfect stillness it seemed the Celestial Palace might have been built around him. His clipped hair was iron-grey with two great scars through it, and his clipped beard was iron-grey with at least three scars through it, and his grey brows were more scar than brow. He looked like a man who had spent half a century falling down a mountain. Perhaps one made of axes.

“Wait,” muttered Brother Diaz. “Cardinal Zizka?”

“Indeed.”

“I understood I was meeting Her Holiness the Pope… to be assigned a benefice—”

“No.”

Could it be that things were starting to look up? Her Holiness might be the Heart of the Church, but she assigned a thousand irrelevant positions, offices, and blessings to a queue of irrelevant priests, monks, and nuns every day, presumably with as little thought as a grape picker gives each grape.

A meeting with Cardinal Zizka, the Head of the Earthly Curia, was another matter entirely. She was undisputed mistress of the sprawling bureaucracy and colossal revenues of the Church. She only took note of the noteworthy. And she had cleared her schedule…

“Well, then…” Brother Diaz wiped sweat from his forehead, dabbed at his fat lip, tugged his skewed habit straight, and began to smile for the first time since he entered the gates of the Holy City. It was starting to look as if sweet Saint Beatrix might have positively outdone herself. “By all means announce me!”

Considering it represented the very pinnacle of ecclesiastical power, Cardinal Zizka’s office was something of a disappointment. A huge space by the standards of a rural monk but made to feel positively cramped by dizzying piles of paperwork bristling with tassels, markers, and seals, deployed on benches to both sides with the precision of rival armies about to do battle. Brother Diaz had expected splendour—frescoes, velvet and marble with gilt cherubs crowded into every angle. But the furniture wedged into the strip of floor between those twin cliffs of bureaucracy might best have been described as dull and functional. The back wall was one blank expanse of stone, strangely rippled as if it had melted, flowed, then set in place, presumably some vestige of the ancient ruins on top of which the Celestial Palace was built. The only decoration was a small and rather violent painting of the Scourging of Saint Barnabas.

A first glance at Cardinal Zizka herself was honestly something of a disappointment, too. She was a sturdy woman with a shock of greyish hair, engaged in taking papers from a pile on her left, signing them in a disappointingly untidy hand, then adding them to a pile on her right. She appeared to have slung her golden chain of office over one of the prongs on the back of her chair, the front of her crimson vestment adorned instead with a scattering of crumbs.

Had it not been for the red cardinal’s hat abandoned upside down on the desk, one could have taken this for the office of some junior clerk, engaged in a junior clerk’s humdrum business. Still, as Brother Diaz’s mother would have said, that was no excuse to let his own standards slip.

“Your Eminence,” he intoned, delivering his best formal bow.

It was wasted on the cardinal, who did not so much as look up from her scratching quill. “Brother Diaz,” she grated out. “How have you been enjoying the Holy City?”

“A place of…” He politely cleared his throat. “Remarkable spirituality?”

“Oh, without doubt. Where else can one buy a desiccated pizzle of Saint Eustace from three different stalls within a mile of one another?”

Brother Diaz was desperately unsure whether to treat that as a joke or a searing indictment, and ended up straining to do both by grinning and shaking his head at once while murmuring, “A miracle indeed…”

Fortunately, the cardinal had still not looked up. “Your abbott speaks very highly of you.” He’d bloody better, after all the favours Brother Diaz had done him. “He says you are the most promising administrator his monastery has seen in years.”

“He does me too much honour, Your Eminence.” Brother Diaz licked his lips at the thought of bursting free from the smothering confines of that very monastery to claim all he deserved. “But I will strive to serve you, and Her Holiness, in whatever capacity you might desire, to the very limits—”

He jumped as the door was noisily shut behind him, spinning about to see the scarred grey man from the bench outside had followed him into the cardinal’s office. Baring his battered teeth, he lowered himself into one of the hard chairs before her desk.

“To the very limits…” persevered Brother Diaz, uncertainly, “of my abilities…”

“That is a tremendous comfort.” Her Eminence finally tossed down her quill, placed the latest document carefully on top of its heap, rubbed her inky forefinger against her inky thumb, and looked up.

Brother Diaz swallowed. Cardinal Zizka might have had the bland office, drab furniture, and stained fingers of a junior clerk, but her eyes were those of a dragon. A particularly formidable example that suffered no fools.

“This is Jakob of Thorn,” she said, nodding at the newcomer. That chopping-block of a face had been troubling in the hallway, but thrust into Brother Diaz’s private interview it was positively distressing. Rather in the same way that finding a beggar in your doorway would be merely distasteful, while finding one in your bed would be cause for considerable alarm.

“He is a Knight Templar in the sworn service of Her Holiness,” said Cardinal Zizka, which was far from an explanation and even further from a comfort. “A man of long experience.”

“Long.” The one word growled from the knight’s immobile mouth like a handful of old gravel between new mill wheels.

“His guidance and advice, not to mention his sword, will be invaluable to you.”

“His… sword?” Brother Diaz was no longer sure where this interview was taking him but did not at all care for the notion that he might need a sword when he got there.

Cardinal Zizka narrowed her eyes slightly. “We live in a world beset by perils,” she said.

“We do?” asked Brother Diaz, and then, having considered it, changed the question into a sad observation. “We do.” And finally to a grim assertion. “We do.” Not personally, in his case, of course.

He lived in a small but actually—now he really thought about it—quite comfortable cell with a view of the sea, and a breeze washing through the windows that at this time of year was rich with the scent of juniper. He had a creeping suspicion the scent of juniper was not among the perils to which the cardinal was referring. That suspicion was all too soon confirmed.

“The Eastern and Western Churches are in schism.” Her Eminence seemed to be glaring right through Brother Diaz’s head into a distance crowded with threats.

“I understand the Fifteenth Grand Ecumenical Council did little to resolve the outstanding issues,” lamented Brother Diaz, hoping to impress with his knowledge of current events and theology at once. He knew the Church of the East had male clergy, that they wore the wheel rather than the circle, that there was some furious row about the date of Easter, but he honestly had almost no understanding of what the deeper divisions were. Few did, these days.

“The many grasping princes of Europe ignore their holy duties and squabble with each other for earthly power.”

Brother Diaz rolled his eyes piously to the ceiling. “They will all face judgement in the hereafter.”

“I would prefer they faced it a great deal sooner,” said Cardinal Zizka, with an edge on her voice that made the hairs on Diaz’s arms prickle. “Meanwhile we are plagued by a veritable infestation of sundry monsters, imps, trolls, witches, sorcerers, and other practitioners of the many foul faces of Black Art.”

Words temporarily failed him, so Brother Diaz contented himself with making the sign of the circle on his chest.

“Not to mention even more diabolical powers, plotting the ruin of creation from the eternal howling night beyond the world.”

“Demons, Your Eminence?” whispered Brother Diaz, making the circle with even greater enthusiasm.

“And then, of course, there is the apocalyptic threat of the elves. They will not stay in the Holy Land forever. The enemies of God will boil out of the east again, bringing their unholy fire, and their unclean poison, and their accursed appetites with them.”

“Damn them,” croaked Brother Diaz, in danger of wearing a circle into the front of his habit. “Is it certain, Your Eminence?”

“The Oracles of the Celestial Choir have been consulted and leave no doubt. We live in a world sunk in darkness, in which our Church is the one point of light. The one hope of humanity. Can we that are righteous suffer that light to be extinguished?”

Here was an easy one. “Absolutely not, Your Eminence,” said Brother Diaz, vigorously shaking his head.

“And in this battle of what can only be described as good, against what can only be described as evil, defeat is inconceivable.”

“Absolutely so, Your Eminence,” said Brother Diaz, vigorously nodding.

“With God’s creation and every soul it contains at stake, restraint would be madness. Restraint would be craven dereliction of our holy duty. Restraint would be sin.”

Brother Diaz had a creeping suspicion that he was somehow straying onto wobbly theological ground, like a clumsy bear chasing rabbits onto a half-frozen lake. “Well…”

“A time comes when the stakes are of such enormity that moral objections become themselves immoral.”

“Do they? I mean—they do? That is—they do. Do they?”

Cardinal Zizka smiled. A smile somehow more troubling even than her frown. “Are you familiar with the Chapel of the Holy Expediency?”

“I… don’t think that I—”

“It is one of the thirteen chapels within the Celestial Palace. One of the oldest, indeed. As old as the Church itself.”

“I understood there to be twelve chapels, one for each of the Twelve Virtues—”

“It is sometimes necessary to draw a curtain over certain regrettable facts. But here, at the very heart of the Church, we must look beyond the mere appearance of virtue. We must tackle the world as it is, with the tools available.”

Was this some kind of test? God, Brother Diaz hoped so. But if it was, he hadn’t the slightest idea how to pass. “I… er…”

“The Church must, of course, remain faithful to the teachings of our Saviour. But there are tasks that must be undertaken, and methods used, to which the faithful and unimpeachable… are not suited.”

Brother Diaz supposed, if you really squinted, you could make that argument, but he didn’t want to be anywhere near it himself. He glanced towards Jakob of Thorn, but found no help there whatsoever. He looked like a man whose methods were deeply impeachable. “I’m not sure I entirely follow—”

“Those tasks are undertaken, and those methods used, by the congregation of the Chapel of the Holy Expediency.”

“By the congregation?”

“Under the direction of its vicar.” And Zizka raised her brows significantly.

Brother Diaz was helpless to prevent his own rising to match. He touched one hesitant fingertip to his chest.

“Her Holiness has selected you for this honour. Baptiste will introduce you to your charges.”

Brother Diaz spun about for the second time to find a woman leaning against the wall behind him, arms folded. He couldn’t have said whether she’d slipped in silently or been standing there the whole time and didn’t care for either possibility. Her origin was hard to place—one of the many shores of the Mediterranean was his closest guess—and she struck him as being every bit as much trouble as Jakob of Thorn, but of an opposite sort. Her clothing was as flamboyant as his was dowdy, her broad face as expressive as his was stern. She, too, had scars. One across her lips. One beneath the corner of her eye, which made him think of a teardrop, strangely at odds with the amused quirk constantly hovering at the corner of her mouth.

She swept off a gold-fringed hat and bowed low enough that her mop of dark curls brushed the tiles, then leaned back with one gold-buckled boot crossed over the other in a display of nonchalance that seemed positively offensive in light of Brother Diaz’s own mounting panic.

“Is she… one of my flock?” he stammered.

That quirk became a grin. “Baaaaaa,” she said.

“Baptiste is what one might call, within the unique context of the chapel…” Cardinal Zizka paused for a moment, considering her. “A lay minister?”

Jakob of Thorn made a strange snort. Had it emerged from any other face, Brother Diaz might have considered it a chuckle.

“Living in a nunnery for a few weeks is as close as I ever came to being ordained.” Baptiste struggled to wedge her unruly hair back into her hat, leaving several stray curls dangling. “It didn’t suit the nuns, but they needed the money.”

“The nuns?” asked Brother Diaz.

“Nuns have to drink, Brother, like anyone else. Perhaps a bit more. It’s been my honour to assist several former vicars of the chapel, including your predecessor.”

“Assist how?” asked Brother Diaz, rather dreading the answer.

Baptiste’s grin became a smile. Behind the scar across her mouth she had two gold teeth, top and bottom. “However was expedient.”

“You seem perplexed,” said Her Eminence.

Perplexed was the very least of it. Brother Diaz wasn’t sure what he’d got into, still less how, but he was developing a strong sense that he wanted to get out of it, and if he didn’t do it soon, it would be too late. “Well, you know… my thing is really… mostly… bureaucracy?” That windowless expanse of stone behind Cardinal Zizka was developing the look of a prison cell. “I reorganised the books. In the library. At the monastery. That was my big… contribution.” He wrestled to minimise the very accomplishments he had spent months outrageously inflating. “Accounts. Paperwork. Bit of negotiation over grazing rights and so forth. Inky fingers.” He chuckled, but no one else did, and his laughter died a death almost as painful as that of Saint Barnabas, in his plain frame on the wall. “So, erm…” he waved towards Jakob of Thorn, “knights, and…” he gestured towards Baptiste, “er…” then realised he had no idea what to call her and gave up, “and devils in the howling night beyond the world…”

“Yes?” asked Cardinal Zizka, with signs of growing impatience.

“It all comes across as a little… outside my experience?”

“Did Saint Evariste have experience when at fifteen years old she took up her father’s spear and led the Third Crusade against the elves?”

“But didn’t she end up getting… a little bit…” Brother Diaz winced. “Eaten alive?”

The cardinal’s brow wrinkled. “We are at war for our very existence against merciless enemies. To win a war, one must, sometimes, make use of the weapons of one’s enemies. To fight fire, one must be prepared to use fire.”

Brother Diaz’s wince grew even more twisted. “But wouldn’t it follow, Your Eminence, that to fight devils… one must be prepared… to use devils?”

Jakob of Thorn rocked his weight forwards, bared his teeth, and stiffly stood. “You see it,” he said.

“This is an enormous opportunity. For your own advancement. For the advancement of the interests of the Church. But most importantly…” Cardinal Zizka rose, plucking her chain from the back of her chair and slinging it skewed around her shoulders, the jewelled circle swinging back and forth. “To do good.” And she jammed her hat on, indicating beyond doubt or hope that the interview was concluded and its outcome irreversible. “Isn’t that why we all join the Church?”

Brother Diaz’s mother had made him join the Church to spare his family further embarrassment. But he somehow doubted that was what the Head of the Earthly Curia wanted to hear. And if there was one thing that was within Brother Diaz’s experience, it was telling people what they wanted to hear.

“Of course,” he said, managing a watery smile. “To do good.”

Whatever the hell that meant.

Buy the Book

The Devils

Excerpted from The Devils, copyright © 2025 by Joe Abercrombie.