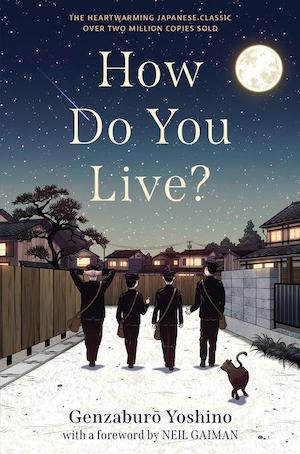

First published in 1937, Genzaburō Yoshino’s How Do You Live? has long been acknowledged in Japan as a crossover classic for young readers. Academy Award–winning animator Hayao Miyazaki has called it his favorite childhood book and announced plans to emerge from retirement to make it the basis of a final film.

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from the novel’s first English edition, translated by Bruno Navasky—available October 26th from Algonquin Books.

How Do You Live? is narrated in two voices. The first belongs to Copper, fifteen, who after the death of his father must confront inevitable and enormous change, including his own betrayal of his best friend. In between episodes of Copper’s emerging story, his uncle writes to him in a journal, sharing knowledge and offering advice on life’s big questions as Copper begins to encounter them. Over the course of the story, Copper, like his namesake Copernicus, looks to the stars, and uses his discoveries about the heavens, earth, and human nature to answer the question of how he will live.

This first-ever English-language translation of a Japanese classic about finding one’s place in a world both infinitely large and unimaginably small is perfect for readers of philosophical fiction like The Alchemist and The Little Prince, as well as Miyazaki fans eager to understand one of his most important influences.

Uncle’s Notebook

On Ways of Looking at Things

Jun’ichi, Today in the car when you said “Humans are really like molecules, aren’t they?” you didn’t realize what an earnest look you had on your face. It was truly beautiful to me. But what impressed me most deeply was not just that look. It was when I realized how seriously you were considering the question at hand that my heart was terribly moved.

For truly, just as you felt, individual people, one by one, are all single molecules in this wide world. We gather together to create the world, and what’s more, we are moved by the waves of the world and thereby brought to life.

Of course, those waves of the world are themselves moved by the collective motion of individual molecules, and people can’t always be compared to molecules of this or that substance, and in the future, as you get older, you will come to understand this better and better. Nonetheless, to see yourself as a single molecule within the wide world—that is by no means a small discovery.

You know Copernicus and his heliocentric theory, don’t you? The idea that the earth moves around the sun? Until Copernicus advanced his theory, people back then believed that the sun and the stars circled around the earth, as their own eyes told them. This was in part because, in accordance with the teachings of the Christian church, they also believed that the earth was the center of the universe. But if you think one step further, it’s because human beings have a natural tendency to look at and think of things as if they were always at the center.

Buy the Book

How Do You Live?

And yet Copernicus kept running up against astronomical facts that he couldn’t explain this way, no matter how he tried. And after racking his brain over these in many attempts to explain them, he finally resolved to consider whether it might be the earth that circled in orbit around the sun. When he thought about it that way, all the various hitherto inexplicable matters fell into place under one neat principle.

And with the work of scholars who followed in his footsteps, like Galileo and Kepler, this view was eventually proven correct, so that today it’s generally believed to be an obvious thing. The basics of the Copernican theory—that the earth moves around the sun—are now taught even in elementary school.

But back then, as you know, it was quite a different matter: this explanation caused a terrible stir when it was first proposed. The church at the time was at the height of its power, so this theory that called into question the teachings of the church was thought to be a dangerous idea, and scholars who supported it were thrown in prison, their possessions were burned, and they were persecuted mercilessly in all sorts of ways.

The general public, of course, thought it foolish to take up such views and risk abuse for no good reason—or else to think that the safe, solid ground on which they were living was spinning off through the vast universe gave them an unsettling feeling, and they didn’t care to believe it. It took some hundreds of years before there was faith enough in this theory that even elementary school students knew it, as they do today.

I’m sure you know all this from reading How Many Things Have Human Beings Done? but still, there may be nothing more deep-rooted and stubborn than the human tendency to look at and think of things with themselves at the center.

*

Whether to consider our own planet earth as just one of a number of celestial bodies moving through the universe, as Copernicus did, or else to think of the earth as being seated firmly at the center of the universe—these two ways of thinking are not just a matter of astronomy. They inevitably circle around all our thoughts of society and human existence.

In childhood, most people don’t hold the Copernican view, but instead think as if the heavens were in motion around them. Consider how children understand things. They are all wrapped up in themselves. To get to the trolley tracks, you turn left from your garden gate. To get to the mailbox, you go right. The grocer is around that corner. Shizuko’s house is across the street from yours, and San-chan’s place is next door. In this way, we learn to consider all sorts of things with our own homes at the center. It’s similar when it comes to people as we get to know them: that one works at our father’s bank; this one is a relative of my mother. So naturally, in this way, the self becomes central to our thinking.

But as we grow older, we come around to the Copernican way of thinking, more or less. We learn to understand people and all manner of things from a broader global perspective. This includes places—if I mention any region or city, you’ll know it without having to reckon from your home—and people, as well: say that this is the president of such and such a bank, or this is the principal of such and such a high school, and they will know each other that way.

Still, to say that we grow up and think this way is, in fact, no more than a rough generality. Even among adults, the human tendency to think about things and form judgments with ourselves at the center remains deep-rooted.

No, when you are an adult, you will understand this. In the world at large, people who are able to free themselves from this self-centered way of thinking are truly uncommon. Above all, when one stands to gain or lose, it is exceptionally difficult to step outside of oneself and make correct judgments, and thus one could say that people who are able to think Copernicus-style even about these things are exceptionally great people. Most people slip into a self-interested way of thinking, become unable to understand the facts of the matter, and end up seeing only that which betters their own circumstances.

Still, as long as we held fast to the thought that our own planet was at the center of the universe, humanity was unable to understand the true nature of the universe—and likewise, when people judge their own affairs with only themselves at the center, they end up unable to know the true nature of society. The larger truth never reveals itself to them.

Of course, we say all the time that the sun rises and sets, and that sort of thing. And when it comes to our everyday lives, that’s not much of a problem. However, in order to know the larger truths of the universe, you have to discard that way of thinking. That’s true when it comes to society as well.

So that moment today—when you so deeply felt yourself to be a single molecule within the wide, wide world—I believe that was a really big thing.

As for me, I secretly hope that today’s experience will leave a deep impression on your heart. Because what you felt today, the way you were thinking your thoughts today—somehow, it holds a surprisingly deep meaning.

It represents a change to a new and broader way of thinking: the Copernican way.

From How Do You Live? © 2021 by Genzaburo Yoshino. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.