The Hokkaran empire has conquered every land within their bold reach—but failed to notice a lurking darkness festering within the people. Now, their border walls begin to crumble, and villages fall to demons swarming out of the forests.

Away on the silver steppes, the remaining tribes of nomadic Qorin retreat and protect their own, having bartered a treaty with the empire, exchanging inheritance through the dynasties. It is up to two young warriors, raised together across borders since their prophesied birth, to save the world from the encroaching demons.

This is the story of an infamous Qorin warrior, Barsalayaa Shefali, a spoiled divine warrior empress, O Shizuka, and a power that can reach through time and space to save a land from a truly insidious evil.

The start of a new fantasy series, K Arsenault Rivera’s The Tiger’s Daughter is an adventure for the ages—available October 3rd from Tor Books. Read chapter 2 below, and check out an illustration from cover artist Jaime Jones. Come back all this week for additional excerpts—keep track of them here!

Two

The Empress

Flowers. Yes, Empress Yui—no, no, that was not the name she chose for herself, and it was not the name Shefali called her. Yui, a single character meant to shame her.

Solitude.

Her greatest friend, as her uncle saw things.

But he was wrong. Besides Shefali and Baozhai, Shizuka’s greatest friends have always been the flowers.

All her life, they have been at her side. One glance outside will show her the Imperial Gardens, where she spent so much of her youth. If she leans back, she can see them, swaying in the breeze outside like the dancers her father so treasured.

It was her father who took her to the gardens. He’d always had a fondness for them. When she imagines his face, she sees a dogwood tree in the background and a sprig of the blooms tucked behind his ear. He is smiling in the midday sun, humming a tune he is too shy to share with anyone else.

“My little tigress,” he’d say, helping her up onto the branches of a cherry blossom tree. He’d touch her on the nose, then pick the brightest flowers for her. Soon they wore matching adornments. “The Daughter is the finest poet in the land,” he said, “and see how her flowers always turn to greet you! She must have excellent taste, for you have always been my favorite poem.”

How many times has she clung to that phrase?

Is it still true?

She shakes her head. O-Itsuki is long gone, she tells herself. Only his poetry remains, dropping from the lips of amorous scholars, lending bravery to the timid.

Only his poetry, and his brother.

Thinking of her uncle makes the Empress wince. Yoshimoto is nothing like his late brother. He does not even have the common decency to share a resemblance. Where Itsuki was tall and thin, Yoshimoto had always been short and stout. Where Itsuki’s cheeks were smooth, Yoshimoto wore a thick beard to hide his youth. Itsuki was a wild maple tree, Yoshimoto was…

Shizuka has never been fond of potted plants. She receives them more than any other gift—but no, she has never liked them.

She leans toward the window, lost in thought, lost in memory. Her eyes dance over poppies and jasmine, irises and hibiscus, champa and magnolia. And, yes—if she looks—she can see the golden daffodil.

Her mother hated that daffodil. So did her uncle.

It stands alone, at least two horselengths from the nearest bush, from the nearest tree. The grass around it is, for the most part, untouched. No one dares venture near it. Shizuka didn’t even know of the daffodil’s existence until one of her walks in the garden.

She was five at the time, she thinks, or perhaps six—before she uprooted the gardens for Shefali’s sake, but after they’d first met. Her cousin Daishi Akiko came to visit from Fuyutsuki Province for the summer. Daishi was so far removed from the bloodline that her children would no longer count as Imperial, but she was the closest thing to a friend Shizuka had.

Well, besides Shefali, but then she has always been an exception. Daishi was only two years older than she, but full of an eight-year-old’s audacity. And while their parents were off at court, Daishi convinced her to raid the gardens.

“Raid.” That was the word she used. They were going to the corpse blossom, she said, and they were going to steal one of its massive petals. Then they’d sneak into the throne room at night to hide it beneath the Dragon Throne. Imagine Yoshimoto’s face! Imagine O-Hanae’s!

But the moment they stepped in the garden, with the sun hanging overhead—Shizuka knew something was different.

As the two girls strolled past a rosebush, Daishi suddenly stopped and covered her mouth. “Did you see that?” she asked.

Shizuka, six, pouted and crossed her arms. “Those are roses,” she said, “not corpse flowers.”

“Walk by them again,” said Daishi.

Grumbling, Shizuka did so, and that was when the shock on Daishi’s face turned to awe. She pointed with her rough little hands. “They’re turning toward you!”

Shizuka rolled her eyes. “Of course they are,” she said. “I’m the heir.”

Daishi would’ve slapped her if she could have—but they both knew she couldn’t. That only made Shizuka more bold. “If I tell them to change colors, then they have to do that, too,” she boasted, and as she spoke, she reached for a pink one.

But then—ah, it was as if the rose fell into a bowl of golden ink, for the color spread through its petals before their eyes.

Daishi fell backwards, gasping, her hair flying out of its neat bun. Shizuka stood staring at the gilt leaves. She reached out to touch them again, only to find that they were as soft as any other rose’s—yet when the light hit them, they shone like her aunt’s hair ornaments.

“What did you do?” Daishi said. “How did you—? That isn’t something people can just do!”

And though Shizuka’s heart was a hummingbird, though her mouth was dry and her fingers trembled, she could not let herself be afraid.

“Don’t doubt me, Aki-lun,” she said.

Daishi wiped her nose and frowned. After getting to her feet, she, too, touched the flower.

Shizuka yanked it out of her hand. “It’s mine,” she said, and tucked it behind her ear as her father did. Daishi could hardly argue the point.

But she did smile. “You’ve got to make me one, too,” she said. And so Shizuka did.

By the start of Seventh Bell, when court finished, Shizuka had changed half the Eastern Garden. O-Shizuru found them laughing, rolling along a patch of golden grass.

But O-Shizuru did not laugh, not at all.

When Shizuka pictures her mother, she sees that look: jaw clenched, thick brows nearly meeting, a look of fear and fury in her eyes.

The moment they saw her, the girls froze, their smiles scattered like dandelion seeds to the wind.

“Daishi-lun,” said O-Shizuru, “go to your father.”

Daishi swallowed. She bowed to Shizuka, apologized under her breath, and ran as fast as her legs could take her.

And so they were alone, mother and daughter. Shizuka’s face felt hot. She hadn’t done anything wrong. Why was her mother so upset?

O-Shizuru thumbed her nose. She looked away for a moment, thinking of something her daughter couldn’t fathom. Then she shook her head. “Who told you about the daffodil, Shizuka?” she said.

Shizuka paused. “No one,” she says. “These are roses, Mother, they’re different—”

“I’m well past the age of knowing what a rose looks like,” Shizuru cut in.

Shizuka winced. Her mother’s warm voice was a sword when she was upset.

O-Shizuru must’ve realized she was too severe, for she sighed and took her daughter’s hand. “Come with me,” she said. “I suppose it’s time you heard the story.”

At the time, that walk had seemed eternal. Frightening, too. Her father never took her to that part of the garden. The farther in they went, the more Shizuka saw random objects sticking up out of the ground—a statue of the Daughter, jade coins. Was that a bamboo mat? What were these things doing in the garden?

But then she saw it, standing alone. A single golden daffodil.

Shizuru sniffed. “When your father and I were wishing for you,” she said, “an old scholar told me I had to bury something I loved.” She gestured vaguely at all the detritus around the garden. “I tried, and tried, with all sorts of things. But when I buried my short sword—that’s when the flower showed up, gold as the sword’s pommel. And then you did, not long after that. It’s been here ever since.”

And Shizuka remembers the breeze through the garden, remembers the daffodil’s quiet dance to unseen music.

She reached out for the flower, but her mother touched her hand. “Don’t touch it,” she said sharply. “The scholar said—Shizuka.” She took a deep breath. “The day you touch that flower is your last day in the Empire. That’s what he said. Do you know what

that means?”

“That I’d be going to live with Shefali and the Qorin,” Shizuka said, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world.

Shizuru palmed her face. “Shizuka,” she said. “You and that girl. Like two pine needles.”

At the time, Shizuka had no idea what it meant. After all, she hadn’t seen Shefali in years, and when she spoke of running off to join the Qorin, it was just something that popped into her head.

But she knew it sounded right.

“I don’t like this,” said Shizuru, more to herself than to her daughter. “Changing the colors of things. Priests telling me they can’t read your fortune, flowers following you around. You should have a good life. A nice, quiet life, with none of my foolishness and too much of your father’s.”

A pause. And then.

“Whatever happens,” said O-Shizuru, “keep Shefali with you. Whatever is going on with you will also be going on with her. Now, come on. Your uncle’s not going to like this, and the Mother knows we’ll hear about it tomorrow.”

Years later, Shizuka can say that her mother was right. The next morning, in full view of the court, the Emperor railed against the perils of hubris, against the ungodly affront to His Divine Power in his garden. His thundering reprimands rained down on O-Shizuru—but she remained kneeling, and if she wanted to gut her brother-in-law like a catfish, she had the good sense not to show it.

Shizuka did not attend court that day. Instead, her parents swamped her with tutors. Calligraphy, poetry, zither, dance. One of them had to catch her interest. One of them would teach her calm, and caution, and to consider her actions.

One did, of course. Calligraphy. But Shizuka had never needed a tutor for that, beyond her brush and inkwell.

But once all that was through—once she made her way home— that was when she heard the words for the first time.

Her mother’s voice near to breaking, her father’s smooth and comforting. They had not yet noticed her.

“What if that Qorin woman was right, Itsuki, what if our girl is—?”

“Then who better to mother her, Zuru? Who better to keep her humble and noble? Better we raise her than Iori. And she will have Shefali, and the two of them will be like two pine needles. She will never be alone.”

Iori. Had that been the Emperor’s name, before the throne? It matched Itsuki, as was traditional for Imperial children. This was the first time she’d ever heard it, but the sad venom in her father’s voice left little room for doubt.

Shizuka’s breath caught. What were they talking about? Was this about her birthday? For she was born on the eighth day of Ji-Dao, the eighth month, at eight minutes into Last Bell in the Daughter’s year. All the palace soothsayers told her it was a good omen.

Though they didn’t use those words.

They just said she was destined for greatness. They said the Daughter had been born on the same day, at the same time.

Is that what her mother meant, in the garden?

A crow’s creaking startled her parents. They saw her then, and their faces softened.

“Shizuka,” said Itsuki, first to rise. He did not wear his normal smile that day. “Shizuka, how were your lessons today?”

Did you mean what you said? Shizuka wanted to ask him. “Boring.”

“Better boring than difficult!” said Itsuki. “What I would give to have a boring day, my dear.”

He hugged her, fixed her hair ornaments, doted on her as he always did.

But something felt different. As if she were wearing another girl’s clothes, as if they were afraid of touching her.

She did not sleep that night. Instead, she stood by the window, staring out at the golden daffodil surrounded by her mother’s old things.

In the morning, her uncle’s men came for her. Twice-eight tall men in Dragon armor, twice-eight faceless warriors with wicked spears, politely asking her to come to the gardens with them. Her mother insulting them. Her father, squeezing Shizuru’s shoulder, telling her that it would pass.

When they arrived, her uncle was already there. His litter was there, at least, held up by eight men, curtained off from the early-morning sun. Shizuka’s mother forced her head down when they approached him.

“Brother,” said Itsuki. “What a beautiful day the Daughter has made! You should come for a walk with us. The scenery will do you good.”

The scenery.

They stood in front of the gold rosebush, and the men in armor had torches.

“Is that what you call this, Itsuki?” said the Emperor. “A beautiful day, and not an affront to our divine authority?”

Shizuka’s chest went tight. “Mother, what is he doing?” “Whatever you’re planning,” said O-Shizuru, her voice harsh,

“you know she meant no offense. We’ve been over this. She is six years old, Iori, six years old, and if you hurt her—”

From inside the litter, the Emperor clapped. Two soldiers stood on each side of Shizuru. Itsuki grabbed his daughter by the shoulders.

“Willful child,” said the Emperor. “Was this your doing?”

She spoke before she could think about it. Things never went well when she honed her thoughts. Then speaking became like dragging knives across her tongue. Talk, she thought. Just talk. The words will come, and they’ll fix everything. They always do.

“Yes,” she said. “It was. All I did was change their color. If you are the Son of Heaven, you can change them back. Gods can do whatever they wish.”

Her father squeezed her tighter. That wasn’t the reaction she wanted! He was supposed to be proud of her, he was supposed to relax!

“The Son of Heaven,” she continued, “shouldn’t have to tell his guards to hold my mother back, either. Are you afraid of her?”

“Discipline her,” said the Emperor.

An eternal moment hung in the air, punctuated by black caws. Shizuka’s heart punched against her ribs.

O-Shizuru stepped in front of her husband and daughter. She didn’t draw the white sword at her side—but her hand was on its pommel. “Go on,” she barked at the guards. “Lay a hand on my daughter, and I’ll lay your hand on the ground.”

“Shizuru—,” said Itsuki.

“I mean it!” roared Shizuru. “Try me, if you are so brave!” The guards all wore masks; Shizuka could not see their faces.

Still, she knew they were pale.

“Wearing war masks to fight humans,” said Shizuru. “To discipline a six-year-old girl. How dare you?”

“Hold the girl down,” snapped the Emperor, “or face Imperial justice.”

Shizuka remembers to this day the rattling of the guard’s armor. Remembers how they stood trembling in front of her mother, remembers the fear in their eyes.

And she remembers her father whispering in her ear. “Shizuka, I’m sorry, but your mother is going to hurt those men unless you kneel. Please play along, and this will be over soon.”

She remembers thinking, distinctly, that she didn’t care if those men were hurt, because they served her uncle.

But if her mother hurt them, then… what would her uncle do? If she gave him a reason, a real reason? What if he sent O-Shizuru North, what if he told the guards to kill her?

Shizuka’s jaw hurt. She didn’t like being this afraid. She knelt. Shizuru started shouting at her, at her father, at her uncle, at the world. Every harsh syllable made Shizuka’s head pound. Fear choked her. Something awful was about to happen, wasn’t it?

Yes.

One of the guards lit a torch, then another, then another, then another.

One by one, they marched toward the bushes. And the others?

The others set fire to the roses. To the jasmine, to the dogwood, to the lilies; to cherry and plum; to all the flowers she’d come to know like old friends.

To all her father’s favorites. Her father held her as they watched, as Shizuka screamed and screamed and screamed.

That day, thinks Shizuka—that was the day she learned to truly hate her uncle.

She sniffs.

To a lesser extent, that was when the public learned to hate him as well. The Hokkarans, that is. The Qorin knew Yoshimoto for a snake before he assumed the throne, but only the destruction of beauty appealed to courtly, art-obsessed Hokkarans.

By the time Shefali next visited, the gardens were coming back to life—but only just. Not that Shefali seems to have noticed. For the better, then.

The daffodil still stands, untouched, unharmed by the fire so many years ago.

Shizuka—no, Empress Yui—shakes herself away from the past. She has spent long enough staring, long enough dwelling in painful memories.

The book in her hands smells of pine and horses. She holds it to her nose and takes a deep breath.

Part of a person’s soul is in their scent, as Shefali would say. Shizuka has long missed this one.

Let the Winds of Heaven Blow

When we were eight and I stayed with you for the winter, your father gave you a choice.

“Either you learn the naginata or the sword,” he said. “You may choose only one.”

You did not have to think about it. “The sword,” you said. “It is about time Mother recognized my talent.”

Your father smiled in his soft way. He reached out to muss your hair. Perhaps he decided not to; he drew back after half a second. But the smile stayed.

“Are you certain, my little tigress?” he said. “The sword may be your mother’s weapon, but it is far more dangerous. You must be closer to your opponent. If we lived in the best times, you would never have to draw your sword; if we lived in better times, you would only fight humans. But…”

“I do not care whom I have to fight,” you said.

O-Itsuki looked away. The smile on his face didn’t change— or at least the shape of his mouth did not.

Once, when he was a young man, O-Itsuki took the field against the Qorin. He did not do much fighting. For the most part, he sat in his brother’s tent, listening to their generals panic.

Many times, when he was a bit older, O-Itsuki accompanied his wife into battle. He did not do much fighting then, either. But he watched good men and women writhe in agony. He watched Shizuru put them down rather than let them become monsters. He watched Shizuru slay creatures twice her size. Perhaps these things were on his mind. But they were not on yours.

“I was born to hold a sword. If the gods saw fit to give my mother one, they’ve seen fit to give me one, too.”

“The gods did not give your mother her sword,” Itsuki said. “Her ancestors did.”

“My mother is an ancestor. I’ll have her sword one day,” you countered. You crossed your arms.

If your father had any more arguments, he did not voice them. Your teacher was selected, and swordplay was added to the schedule of your daily lessons. You left the room triumphant. For the rest of the day, it was all you could talk about. During our walk around your gardens, you spoke of it.

“A sword, Shefali!” you said. “At last! Now that I’m being properly taught, my mother will have to recognize my talent.”

Only the plum trees were blossoming. We stopped beneath one of them. Was it my imagination, or did the flowers turn toward you as we approached?

I plucked one of the sprigs of flowers, already tall enough to do so. I can’t say what possessed me to do it—the penalty for defacing the Imperial Garden is twenty lashes, at minimum. Perhaps

I knew you’d never go through with such a punishment. What I did know, as soon as the flower was in my hand, was that it deserved to be in your hair. I stopped us with a small motion, swept your hair back between your ear, and slipped the flower there. The bright pink petals echoed the ones on your favorite winter dress.

What a pretty sight you were. I got the feeling it would be strange to tell you that you were pretty—that you might take it differently than you did when other people said it. So I changed the subject.

“Why not a naginata?”

You scoffed. “The weapon of cowards,” you replied. “The weapon of those who think our only enemies come from the North.”

And so we stood beneath the plum tree and spoke of other things. You spoke, and as always, I listened.

Two days later, your mother returned from her assignment in Shiratori Province. In those days she left often. On that particular morning, your mother returned with a man on a stretcher. We were not told what had happened, and in fact, we did not learn your mother was back until she called the two of us to meet her.

We stood in the healer’s rooms. She was a stooped old relic, with more bald skin than hair and more hair than teeth. And yet, despite her appearance, she was no older than twenty-two. Such was the life of a healer.

When we entered the room, she tried to shoo us away from the man in the stretcher. “This is not a sight for young eyes,” she said.

But I’d seen men die before this. I did not move. And you were made of iron and fire; you did not move, either.

“Leave them be, Chihiro-lao,” your mother said. “They are here on my command.”

“I am going to put this man down, O-Shizuru-mon. You cannot wish for them to see that,” she said.

But your mother paid this no heed, and came to kneel at our side. “Shizuka,” she said, “I understand you’ve chosen the sword.” “I have,” you said. “And nothing you can show me will change

my mind.”

“I thought you might say that,” said Shizuru. “Shefali-lun. Have you seen what happens to those who challenge your mother?”

I thought of Boorchu and nodded. “Was it fast?”

Again, I nodded.

“That is because your mother is an honorable woman,” Shizuru said. “At least as long as the situation calls for it. What I am about to show you is different. If you both insist on leading a warrior’s life, you must know what happens when you are not careful.”

I’d done no such insisting. On the steppes, you are either a warrior or a merchant or a sanvaartain, until you are old enough to simply be an old person. But I did not want to correct a woman who slew demons for a living.

“Step aside, Chihiro-lao.”

The healer lumbered out of the way.

The man in front of us was a man in the loosest sense of the term. How long had it been since he was infected? Black coursed through his veins, black pulsed at his temples, black blossomed at his throat. His skin was pale and clammy. An unbandaged stump remained where his arm should’ve been. His eyes were closed, but his face contorted in pain. As we watched, shadows played beneath his skin, forming faces with two mouths and too many teeth.

Sometimes we’d hear a popping sound, and one of his limbs would snap out of place—with the man himself not moving at all.

“This man slew a demon today,” your mother said. “But he made the mistake of letting its blood mingle with his. When he dealt the beast its killing blow, a gout of it landed on the stump of his arm.”

The man thrashed. Your mother drew her sword.

My eyes flickered over to you. There you were, still as the noontime sun. You clenched your jaw and creased your robes with white-knuckled hands. Ah, Shizuka, you tried so hard to tear yourself away from what you were seeing!

“He is having a violent reaction,” your mother continued, stepping toward him. “Normally he would lie in bed and rot of a fever before he began thrashing.”

The healer smothered him with a pillow while your mother wrapped her hands in cloth.

You reached for me.

Your mother made a clean slice.

There was a soft sound, then an awful smell. It was done. Shimmers clung to the underside of the pillow as the blood seeped up into it.

Chihiro-lao winced. She looked right at the two of us and mouthed, “I’m sorry.” You weren’t looking at her, but I was, and I appreciated that moment of warmth. Children remember who showed them kindness when the world tried to make them cruel.

This was necessary cruelty, but it was cruelty all the same.

I gave her a little bow from the chest. It was the least I could do to thank her. Satisfied that my soul wasn’t lost, she made the sign of the eight over the man’s body. Then she bowed to your mother and left.

She must have gone to fetch people to move the body. You needed at least four to do it safely, and though she was young her body was not. It would have to be five.

O-Shizuru tore the cloth off her hands and wiped her blade clean. When she glanced at us, we still had linked hands.

“When you use a sword, Shizuka,” she said, “you must get close to your opponent. And when your opponent’s blood is a poison to the gods themselves, you must be careful.”

Shizuru must’ve expected you to buckle. Instead, you ground your bare heel into the floor.

“Careful?” you roared. “I am O-Shizuka, born on the eighth day of the eighth month, eight minutes past Last Bell. I don’t need to be careful of the Traitor, Mother. He needs to be careful of us!”

And so you turned and stormed off before your mother could say anything.

You did not run. Instead, you walked as fast as you could while maintaining a degree of grace. Soon the plum tree rose above us, and soon we stood beneath it again. You stared up at it as if it offended you, and you finally snatched a fruit from it the way a queen backhands an unruly servant.

“Shefali,” you said, “promise me something.” I nodded.

“If I am ever foolish enough to have that happen to me, you will put me out of my misery within the day.”

And at this, too, I nodded.

I nodded because I was eight, and you were asking me to promise something that I never thought would happen. Because we were eight, and battle was still a distant dream in our minds, no matter how often we’d seen its effects. Because we were eight and standing beneath a plum tree, and nothing could hurt us.

* * *

The next day you began your formal swordplay lessons. And, yes, it’s true—from the moment the wooden sword touched your hands, you were a natural. As a horse is made to run, so you were made to wield a blade. Your strokes painted bruises on your instructor like ink on paper.

But I was not so talented.

Hokkarans favor straight swords. They’re well suited to your obsession with showy duels. On horseback it is different: a straight blade gets caught in your enemy’s neck, and you can hardly stop to retrieve it. A curved blade is more practical.

Your instructor was an old man from Shiratori Province. The long years of his life bent his back and hobbled his knees, but with a sword in hand, he was spry as a youth. Complicated forms were to him as simple as rising up in the morning. Perhaps easier, given his age. He’d fought in the Qorin wars against my mother. Everyone his age had. But the color of my skin was the least of his concerns.

“Oshiro-sur!” he’d shout, the veins in his neck pulsing. “Have you no grace? I ask you to be flowing water; you are a cliff face!” I frowned. I could be flowing water. When arrows left my bow, they were rain falling from the sky. When I was on my horse, we were the rampaging rapids of the Rokhon.

But put me on my feet, put a straight sword in my hand, and ask me to move like a dancer?

You noticed my discomfort.

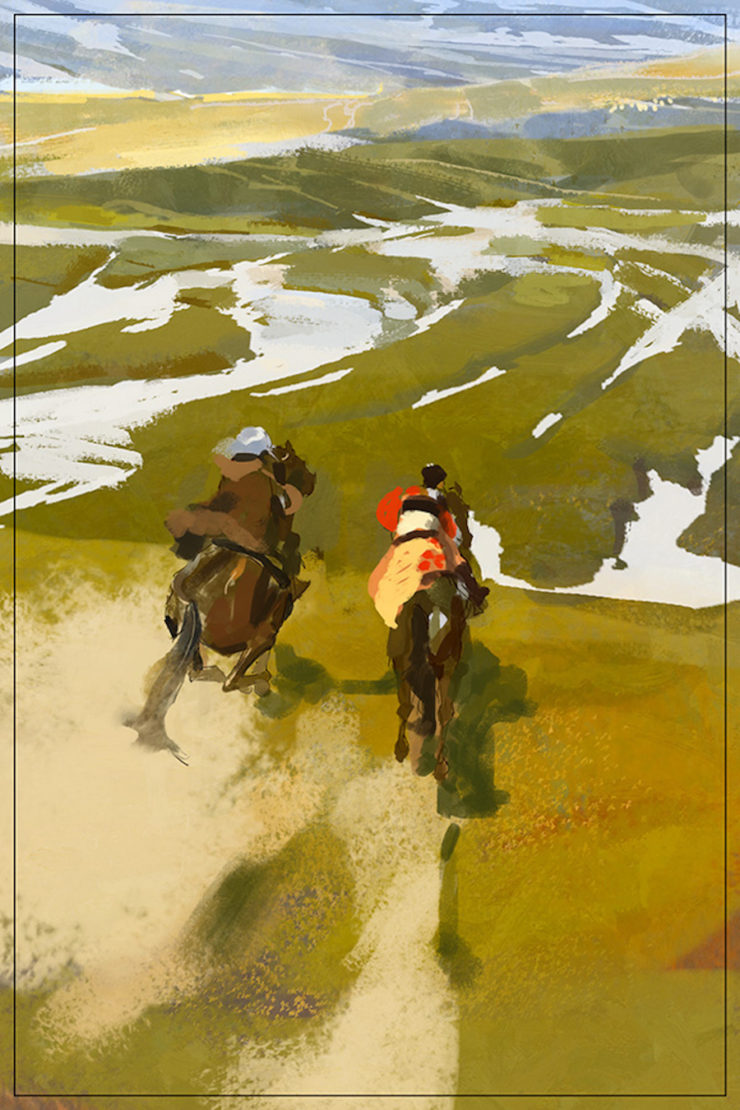

As the days wore on into months and the Daughter brought spring back to the lands, you insisted we go riding after sword lessons. The forests around Fujino were dense, and from your castle we could see the morning fog like a cloud come down from the heavens. It stayed until midday, when Grandmother Sky called it back. White on emerald green, vibrant and pale; the sight itself refreshing and enticing.

It was your great-grandfather who commissioned that forest. In his day, it was only a thick circle of green around the palace. He was an avid hunter and wanted a place to keep his more dangerous game. Here, where he kept wolves and tigers and bears, you wished to hunt.

“Come,” you said. “My men always go hunting in that forest; they never take me along. Too dangerous for an Imperial Flower, they say.”

Forests intimidated me as much as castles did. No roof is a good roof, whether it be carved stone or a branch. I kept calm by remembering I’d see patches of blue, at least. Maybe I could stitch them together and make a patchwork sky.

I was too distracted by my little mental sewing experiment to keep track of where we went. Only when the scent of horses came to me did I realize you’d led us all the way to the stables. How you did it without anyone questioning us is beyond me—but then again, who would ever question you?

Once I realized our horses were nearby, a grin spread wide across my face. I could feel my gray nearby, I could feel her in my bones. How far would we ride? The forest was large. My gray didn’t have much experience navigating thorns and brambles. Would she be all right? Perhaps I should pack extra sweets… she likes them far more than any horse of her caliber should. They’re ruining her teeth. But how am I to deny her? How can anyone look into those soulful pools of brown and deny them a sweet?

“Your Imperial Highness, are you well?”

Ah. Right. In Hokkaro, you had hostlers instead of tending horses yourselves. This man was their leader if the plume on his cap was any indication. I’d forgotten his existence, and his voice startled me.

Before you opened your mouth to berate him, I touched your hand. You stopped and looked at me; I pointed to our horses.

“Ah, that’s right,” you said. Then you called to him. “Boy, ready our horses.”

“O-Shizuka-shon,” said the head hostler. “That Qorin girl touched you—”

You waved. He scrambled to his feet and prostrated himself before you. “That Qorin girl is Oshiro Shefali, my good friend, and you will treat her with the same respect you treat me.”

By then I had already begun preparing your red gelding. Hokkaran saddles are different; where we have stirrups, a horn, and a high seat, you have little more than a flap of leather. Hokkarans believe that a rider and horse should communicate without words. That is the Qorin way of thinking, too; except that we recognize the usefulness of gestures.

You banished the head hostler to his chambers. I helped you up onto your horse and swung into my own saddle. My horse nickered. I ran my fingers through her mane. Again, she nickered— but this time she stamped her hoof, too. A dark mood, then.

So I leaned forward and whispered to her. In hushed Qorin, I spoke to her of the sweets that awaited her at the end of the day, of the verdant places we were going, of home, of grass and wind.

As the words left me, my throat thrummed with more than air. No, this was a great wind. This was the voice of something larger than myself, compressed into a whisper.

It was then I realized I was no longer speaking Qorin. Imagine a language like swaying grass. Imagine vowels sounded like a seer’s horn, consonants the rattle of bones in her cup. My tongue was thick with the taste of loam.

My horse calmed.

I felt like an empty river. I opened my mouth and stared at my hands and tried to understand what had just happened. And, as I did whenever I was confused, I turned to you.

And there you were, sitting atop your horse like a throne. When you saw the expression on my face, your brows knit together. “Shefali?”

I closed my eyes and squeezed my hands together. Opening them took some effort. Were they still mine, or were they, too, the tools of something else?

You urged your horse toward me. There, just outside the royal stables, you squeezed my shoulder. Golden butterflies pinned to your hair fluttered the closer you moved.

“Shefali,” you said.

I licked my dry lips. A deep, rattling breath shook me. “I am all right,” I said.

“You aren’t,” you said. “Do not lie to me. I know you as I know my reflection. What happened?”

I met your eyes. I could not meet them long. The second we locked gazes, my chest throbbed and ached and rang with a note I did not recognize.

You, too, flinched. Your ring-covered hand flew to your heart. “Did you… ?” you asked.

I nodded. When you turned to look around us, the ornaments in your hair sounded like temple bells.

A messenger rode up toward the stable cloaked in yellow and white—the colors of Shiseiki Province. Upon seeing you, he bowed at the waist, still mounted. “O-Shizuka-shon! Flower of the Empire! You honor me with your presence!”

Even at eight, you did not bat an eye at such praise. If anything, I think it exhausted you. When it came to you, the public knew only three ways to speak. The hostler earlier demonstrated mindless concern well; to those people, you were not a girl but a precious, frail object. The second thing a person might do was praise your parents. This did not trouble you much on its own, but by the third or fourth time you heard someone remark on your semblance to your mother, you made your excuses to leave. And here was the last: mindless praise from a passing messenger.

Seeing you alone was considered a great honor; you did not have to further honor him with words. No doubt this messenger would tell his family all he could about you: the colors you were wearing, the way you carried yourself, the small nod you gave him as he left.

Perhaps he’d mention how long your sleeves were, or the elaborate dragons embroidered in gold thread upon them. If he was an astute man, he’d mention the chrysanthemums secreted away by your wrists.

But he would not have mentioned how your hand gripped my wrist, how you squeezed mine when he called to you.

Long sleeves hide many secrets.

“We’re going,” you said. “We cannot talk here.” I nodded.

Together we made our way out of your lands. In spite of our age, no one questioned us. Why would they? You, the Imperial Niece, were old enough to go out on a ride if you so wished. You had company. Qorin company, yes, but that was perhaps for the best. Everyone knows my people are born on horseback and sired by stallions.

On any other day, you consider silence an enemy you must cut down. As our horses took us from the palace of Fujino to the deep green forests surrounding it, you spoke not a word.

But then, neither did I.

I was marveling at the trees, for one. Wondering how anything the gods created could be so tall. Wondering what it was like to climb up onto the highest branches of the tallest tree we passed. What did your palace look like from there? Which was taller— a tree that grew from a sapling over dozens of years, or a palace men raised with their own hands?

After five hours of riding in silence, I called for a stop. Our horses needed water and rest.

We stopped in a relatively light portion of the forest. A small pool lay beneath the trees. From it our horses drank, from the grass surrounding it, they ate.

And as for us?

I laid out a thick felt blanket made by my grandmother. At one time, it had been white, but the grit and grime and sweat and smoke of our lives tinged it gray. My mother let me take it from her ger before leaving me with you. Such a thing was normally not permitted—but then, I would normally not be leaving the ger for so long.

On this blanket you sat. On this blanket, with wool taken from my grandmother’s flock. Your dress was blood on smoke.

“Shefali,” you said, “have you ever seen a man die? Besides the tainted one my mother killed?”

I started. What sort of question was that? And yet…

Boorchu calling me a coward. Claiming my Hokkaran blood made me weak. The sight of him crumpling to the ground.

I nodded.

Clouds shaded your brow; the bright ornaments of your hair could not illuminate the darkness of your mood. When you spoke next, you stared at the ground.

“Shefali,” you said. As an inkbrush tints the water it touches, so did fear darken your voice. “What do you see when men die?”

My lips were dry. Dew on every leaf near us—but my lips were dry.

Because I knew the answer.

“Their souls,” I said. “I see their souls.”

On the blanket your hand twitched. You huddled in on yourself.

“Shizuka?”

“Right before I was born,” you said, “my mother was with yours, out on the steppes.”

I tilted my head. This I had not known. What was Shizuru doing on the steppes in such a state? For my mother, it is to be expected. But for a Hokkaran woman with a moon belly to be riding? To be riding in the winter?

And people say that you are foolhardy.

“Alshara insisted on taking my mother to an oracle before the week was out,” you continued. “And in this, as in all things, my mother listened to yours.”

“The oracle could not read my future,” you said. “When her bones fell to the ground, they shattered into dozens of tiny pieces. She said she’d heard of that happening in stories, in the presence of gods. So they went to another oracle, and another. Every time they tried to read my fortune, the same thing happened. Hokkaran fortune-tellers only said my birthday was important; they couldn’t say anything about my future.”

Around us, a hundred creatures lived their small lives. Trees and roots and mushrooms alike bathed in the fading light of the sun. Trickling down through the branches, the sun painted us, too, with streaks of white and yellow, with bright patches like oases on our shaded faces.

As the priests told things, each of those animals, each of those plants, and even the rocks around us were gods. Some gods are grains of sand; some are Grandmother Sky. A god can be anything it wishes—as small or large as it pleases. A god may live in a singing girl’s zither, imbuing each note with the sweetness of a ripe plum. A god may choose a scabbard as its home, and lend any blade it touches sharpness unmatched. Or a god might also live in a crock and burn everything it comes into contact with.

Gods can be anything. But could we be gods?

Two pine needles, my mother always said, like two pine needles…

You pointed to a particular tree some distance away. Perched on one of its branches was a bright green songbird, the sort people travel into the forest specifically to catch. At the right market, it would fetch a fine price.

“If I asked you to shoot that bird,” you asked, “you would be able to, would you not?”

I frowned. I didn’t really want to shoot that bird—someone hungrier than we were might need it in the future. Nevertheless, I swallowed my protests and nodded.

“Sitting here with me on this blanket,” you said, “you could draw your bow, fire an arrow, and rob this forest of a singer.”

It would not be an easy thing to do. Qorin bows are made to be fired from compact spaces; sitting was not the issue. Drawing it without startling the creature would be the problem.

And yet I knew I could do it. As that same bird was born knowing a hundred songs, I was born knowing a hundred ways to fire a bow.

“Does it not occur to you how strange that is?”

Strange was a walking fish. Strange was water spreading out across the horizon no matter where you looked. Being able to hunt was not strange. It was a skill I needed if I was going to feed myself out on the steppes.

“You are eight.”

I gave you a level look.

“You are eight and you can strike a target as small as my fist from this far away,” you said. “Shefali, there are grown men who cannot do that.”

“Then they would starve,” I said.

You sighed and shook your head. “Earlier,” you said, “when you spoke to your horse—did you not feel strange? Did you not feel like someone else’s inkbrush?”

I stared at the backs of my hands. Warm, brown skin, pockmarked here and there with unhealing white. If I made a fist, I could see my pulse throbbing. I counted the beats, waited for you to continue. If someone was using me as their brush, what were they writing?

You swallowed. Near to us was a shrub full of blossoms I could not name. They were all bright violet—so bright, I did not like to look at them. You reached out toward one of them. It struck me that your hand shook, that there was this fear in your eyes you cut down like an enemy on the field.

When your fingertips met the petals, they turned from violet to gold.

A soft sound escaped me, and I covered my mouth in surprise. “Shefali,” you said, and you took my hand in yours. I could not help but stare at you—your pleading mouth, your wide eyes. “As candles are not stars, we are not like the others. You must promise me, no matter what, that we will always find our way back to

each other.”

Your words hammered against the bell of my soul. “I promise,” I said. “Together.”

“Swear it,” you said. The fire of youthful conviction filled you. “Swear it to me.”

Without hesitation, I stood up and walked to the great white tree on which the songbird sat.

When you walked to me, it was without fear, without a trace of nervousness.

I drew an arrow from the quiver hanging at my hip. I held out my hand, the flat of the arrowhead resting on my palm. Then, together, we cut our palms against it.

Sharp pain jolted through us. And yet neither of us flinched.

When I drew my hand back, the arrowhead was dark with blood. It stuck to my palm, and it was only with some effort that I removed it. Then I nocked the arrow. Sweat and grime from my grip pressed into the weeping wound we’d just made.

When I drew back the bowstring, when the pressure against my palm set my whole arm alight, when the pain screamed inside me—when all these things happened, I pointed my bow at the sun. “I swear by sky and blood,” I said. “I swear by my mother’s ger, and my grandmother’s spirit. I swear by the blood of Grandmother Sky, who birthed the Qorin and taught us to saddle lightning. Together. I swear this.”

Only then did I loose.

Like the songbird, the arrow soared overhead, straight on toward the sun. I turned before it reached the peak of its arch. Once Grandmother Sky tastes your blood, you may not hide from your oath. Where can you go to hide from her bright gold eye, or the dull silver one? All things return to the sky in time.

As we walked back to the blanket we called our camp, I wondered if we would return to the sky.

Only the stars and the clouds deserved to be in your company. Only the sky could be home to you. Only the sky was a splendid enough throne for you.

Excerpted from The Tiger’s Daughter, copyright © 2017 by K Arsenault Rivera.