I was seven years old the first time my uncle poisoned me…

Outwardly, Jovan is the lifelong friend of the Chancellor’s charming, irresponsible Heir. Quiet. Forgettable. In secret, he’s a master of poisons and chemicals, trained to protect the Chancellor’s family from treachery. When the Chancellor succumbs to an unknown poison and an army lays siege to the city, Jovan and his sister Kalina must protect the Heir and save their city-state.

But treachery lurks in every corner, and the ancient spirits of the land are rising… and angry.

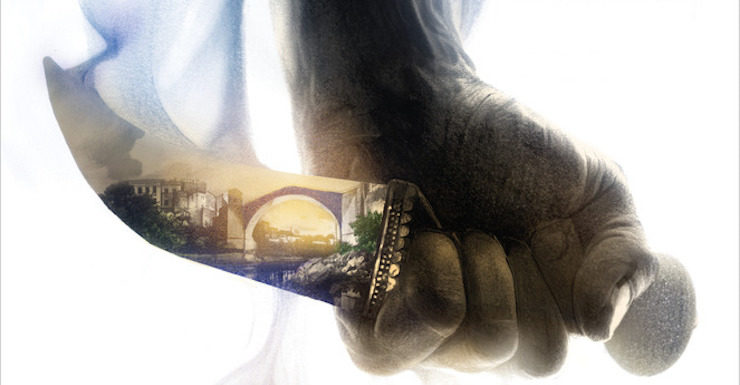

City of Lies is the first novel in the epic fantasy Poison War series from debut author Sam Hawke—available July 3rd from Tor Books. Read part 3 below; you can start with chapter 1 here, and come back all this week for additional excerpts.

2

Kalina

(Continued)

Buy the Book

City of Lies: A Poison War Novel (The Poison Wars)

Morning dawned without symptoms and the physics cleared us to leave. Lord Ectar was asked, in the politest possible terms that could be backed up with a sword, to accompany the Order Guards who had guarded our room to the Manor.

“I’ll go with them,” Jov told me. The creases around his eyes and brow and the redness of his irises gave away his lack of sleep. My heart ached for him. Sleep had been a brief escape for me; my brother would have spent the whole night trapped in his own head, imagining things that he could have done differently, berating himself for the path of his own thoughts. “You go home and rest.”

As if home, empty of our Tashi, would bring rest for either of us. “I’ll send a message to the estate,” I said instead. “If I go now I might not get trampled.” Most, if not all, of the Council would have heard the news last night. All the Credol Families owned birds to communicate swiftly with their family in the other cities and their estates; it would be crowded at the cote before long.

“Take a litter,” he said, frowning at me even as I slipped off. Well out of anyone’s earshot, I let out the cough I’d been smothering. My chest hurt and my breath came shallow and fast. Thendra crossed my path on the way out of the hospital, and the dark creases fanning out from her eyes deepened as she looked me over with swift appraisal.

“Go home and rest properly, Credola,” she warned me. “You should not push yourself so hard. The last thing you need right now is a relapse, yes?”

She was right, of course, even if I resented her for it a little. The cote was at the southern base of Solemn Peak, a fair walk from the hospital. Though I’d been working on my strength, it seemed spent today all the same. It was barely dawn, but the hospital was good business for the litter carriers and I found a pair easily. They were fit men who sang old religious songs inharmony as they jogged me south along the lake path. I envied their lungs.

As we passed Bell’s Bridge, the great bell tower by the Manor rang out a solemn peal, and kept ringing. The carriers slowed in surprise, speculating in anxious tones. “It’s the Chancellor,” I told them quietly. The man in front twisted to stare at me, shock stopping him in place. “To the cote, please,” I reminded him, and he gripped the edges of the litter tightly and took off at pace.

The cote was a rough tower built into the stone so the birds could nest naturally in crannies in the rock. If not for the orderly spacing of the nests it would almost seem like a natural breeding space. Some of my peers in the Administrative Guild hated coming here with missives, preferring to send messengers or servants. I liked it: the strong, earthy smell, the streaks of bird droppings that striped the insides black and white, the chorus of the birds’ raucous chatter echoing around. It was quiet—I’d apparently beaten the other Credolen here—but the door was open. “Hello?” I called, approaching the opening. Unease settled over me. I cleared my throat. “It’s Credola Kalina. From the Administrative Guild.”

The bird keeper edged out, slablike arms encircled with heavy claw-scratched leather bands, her trepidatious mannerisms at odds with her rectangular chunk of a body. “Credola,” she said, wringing her hands. “I heard the bells, and I knew people would come. I didn’t know the tower was weak, honor-down, I swear it was sound.…”

Following the keeper into the cote, the blood pounding in my ears was the only sound to be heard. Through the jagged mouth of a hole in the top corner of the tower a pale blue patch of wrongness gleamed. Scattered beams of light sprayed down into the cote, long white fingers pointing at empty hollows where the gray-and-white birds should have nested. “The birds…”

“They’ve flown,” the keeper finished. “All the tourists. They’ve all gone home, and no messages on them! Today, of all days.”

Tourists were birds not from this cote; released, they would fly to their own home cotes. “All of them?” I asked, dismayed. There should have been dozens of tourists here; the city birds, for official use, as well as the private flocks housed here for a fee and owned by some wealthy merchant families and all of the Credol Families, including mine, for messages between Silasta and the other main cities, and to the country estates. But the only birds to be seen were marked with white tags on their legs, indicating they were trained for this cote, and the locals were no use at all. They wouldn’t fly anywhere but to their own familiar nests located right here.

“All of them.” The keeper pointed one thick finger at a pile of collapsed rock and root-bare shrubbery. “It must have been a rockslide during the night. I came in to feed them this morning and found it like this. A few of the locals went out to explore, but most have come back. The Oromani bird is fine,” she added, quickly pointing out the gray-chested bird, which had arrived with a message from our steward a few weeks ago and was waiting to be taken back with a courier.

Fat lot of good the locals will do us, I thought, but the poor keeper already looked distraught enough. Prob ably afraid of losing her job. And with good reason, too; I doubted the Credolen would take well to the news that they’d have to inform their families about the death of the Chancellor by courier instead of bird. While boats could reach Telasa downriver in a day, the journey upriver to Moncasta would take far longer, and West Dortal even longer, by road. For those who had close family on their country estates, the delay would be substantial, even with the best couriers.

The feeling of unease strengthened as I stared up at the hole again. It was just an inconvenience, I supposed, but it somehow felt like more than that.

“Stay here,” I said, trying to sound authoritative. “We’ll get someone from the Builders’ Guild here to patch the roof so no predators get to the rest.” And my own Guild would need to be informed that there was going to be a sudden demand for couriers. Maybe there would need to be some kind of central organization for how we spread the word. We’d have to inform our neighbors and trading partners, and there were only so many messengers in the city.

I’d wondered yesterday how we would get through life without our Tashi. Perhaps this was how people did it; letting themselves be pulled to and fro between things that must be done, obligations and decisions and more decisions. It was easier than thinking. Definitely easier than feeling.

* * *

Inherently suspicious, my brother took the news of the damaged cote with unease. What’s the difference between a coincidence and a pattern? Etan used to say.

“What happens next…” Jovan murmured, as if answering my thought.

We had been allowed in the Manor, though our time was limited. Tain had called a Council meeting and even now the others would be gathering in the Council chamber. The three of us sat in the mess of his sitting room—the surfaces bare, the floor strewn with belongings he’d hurled in his rage and grief—clinging to the last few moments we had. Tain looked a wreck; I doubted he’d slept at all.

After hearing my report on the birds, Tain had spoken to the Stone-Guilder, Eliska, and she’d sent builders and an engineer from the Builders’ Guild both to repair the cote and to report on whether the rockslide had been natural. There was no specific reason to connect the damage to yesterday’s events, except timing, but it was enough to concern Jovan and me. Tain seemed dazed, willing to take our advice on what to do next, and I worried how he would cope with the Council meeting.

“You’ll need to talk to the Scribe-Guilder,” Jov said. “To manage the priorities for who gets informed when. We can send a boat in each direction, and a messenger by road west, perhaps one messenger per estate, one for the army, as well—do we wait to inform other countries?”

“I’ll consult with Budua,” Tain agreed. “I don’t know enough about our international relations. About anything.” He stared at the wall, face shadowed. He hadn’t expected to replace his uncle for decades or longer. We’d all thought we had so much time.

One of Tain’s servants interrupted us politely with a tray of food. Once he left, Jovan pulled the tray out of Tain’s reach and examined the plate of fruit and three bowls of baked fish. “From now on, you eat nothing I haven’t prepared.”

Tain regarded him with a strange look and tense shoulders as Jov started his pro cess, sniffing everything, separating the components of the food with his fingers. This was the inevitable progression of their friendship, and hardly unprecedented, but from the range of emotions tugging at his expression it seemed Tain had avoided thinking about that. Undeniable, too, was the kernel of dread in my stomach. Yes, this was our family’s duty, and protecting Tain was an honorable task. But could Jov protect Tain if Etan had failed to protect Caslav?

“What do I say about what happened yesterday?”

Tain’s question forced us to an uncomfortable place, and we were silent a moment. “I suppose you have to say it seems to have been a disease or toxin carried by the leksot,” Jov said at last. “You can tell them you have Lord Ectar in custody for questioning as a precaution, but that at this stage it doesn’t look deliberate.”

“Was it, though?” Tain looked between us, eyes red. “Was this just an accident?”

“I don’t know,” Jov said. “Honor-down, it wasn’t a poison we know of, but Thendra said it didn’t act like any disease she knew of, either. If Ectar’s telling the truth about the animal being healthy during the trip here, why did it only die yesterday, without sickening?”

“I don’t even know what to do with Ectar. He’s related to the bloody Emperor; I can’t accuse him of anything without good evidence.”

I cleared my throat. “I’m not even sure the leksot was connected. Someone could have poisoned it, too, to throw suspicion on Lord Ectar.” When Tain looked surprised, I elaborated. “I found the leksot in the glass gardens, but someone else had been there, too. There were crushed weeds by the pond, footprints, and the way I found the body didn’t look right. I think… I think it’s possible someone laid it out for us to find.”

Even as I said it, I wondered if it sounded paranoid. My brother looked at me strangely, not in condescension or judgment but rather, an uncertain reevaluation. He trusted me, but he didn’t understand everything about me. He wasn’t the only one who had been trained to a duty.

“Plenty of other people were at that lunch,” Jov agreed slowly. “I don’t think we should ignore other options at this stage. Don’t tell the other Councilors you suspect anything but a disease. Thendra is examining our uncles’ bodies this morning. We might know more after that.”

“So I just have to hold off that baying pack in the Chamber in the meantime.” Tain managed a weak grin. “Should be no problem.”

* * *

The two of them sent me off home, again, when time came for the meeting. I couldn’t deny my exhaustion, but their well-meant concern stifled me. I had lost my uncle, too, and that same family honor tied me to protecting Tain as much as my brother. So I nodded meekly and exaggerated my weariness so as to be outpaced. When they’d passed from my sight down the spiral corridor, I slowed further, waiting until their footfalls pattered away.

I removed my sandals and tucked them into the cording of my dress. Evading servants was easy enough. They were distracted and unsure, and I was a silent ghost, moving barefoot through rooms and corridors I’d not visited in years. My heart beat fast as I wobbled on top of the cupboard in the dusty storeroom at the end of my journey. Ghost or no, I’d be in trouble if anyone disturbed me now.

The panel stuck and I had to pry it open; no one had used it in years. Inside was a tighter fit than I remembered, and the darkness and heavy air more intimidating. Though perhaps that was because my memories of this place were as a young woman desperate to impress an uncle she’d long thought was shamed by her failures. It had been a game I was good at—at last, something I could do well!—being quiet, being underestimated, and listening, always listening. My throat constricted again as I remembered the warmth of my Tashi’s praise. A secret only he and I had shared, and something no one else ever knew about me. Not even my little brother. The loss of Etan beat inside me like a hammer, but I crawled on.

The murmur of voices alerted me that I’d reached my destination long before my fumbling fingers found the latch in the dark. It opened soundlessly, giving me a sliver of a view down below. I settled into the small alcove and pressed close.

The chamber was a comfortable room, designed for long hours of discussion, with soft thick carpet and plush chairs around a circular polished stone table, and cabinets stacked with expensive ornaments and artifacts. All the great and terrible decisions of Sjona’s past had been made right here beneath the enormous glass-and-metal dome roof. How many had been observed by someone in this hiding place, all but invisible between carved panels depicting the histories of the peoples who had come together to form a country of peace and prosperity?

Jovan sat in my uncle’s chair; behind him hung Etan’s portrait, his gentle face inclined slightly downward as though watching over his nephew. Between him and Tain was an empty seat, Chancellor Caslav’s solemn face above it, gazing off to the side in contemplation. To Jov’s left were the other four Credol Family seats, organized in order of the strength of their relationship to the Chancellor. I catalogued them now as Etan had required of me in the past: Bradomir, impeccable from fingernail to groomed moustache; Lazar, shrinking into his seat, a disheveled ghost of his usual self. The other two—plump, handsome Javesto and shriveled Nara—an exercise of contrasts; one bold, careless, squandering family fortune and sometimes honor in dubious business arrangements, the other bitter, miserly in her protection of power and money.

To Tain’s right, the six Guilders: Warrior, Craft, Artist, Stone, Theater, and Scribe, the difference in their levels of haggardness marking who had heard the news last night and who had woken to it this morning.

“It is imperative that I be able to send the best couriers immediately, Honored Heir,” Credo Bradomir was saying, leaning past Jovan toward Tain. “Much of my family is in Moncasta at this time of year. It will be difficult for them to return for the funeral if I am forced to—”

Credo Javesto snorted. “We can’t wait for every one’s family, friend, or the funeral won’t be for a month.”

“Forgive me, Credo, but as someone who is terribly young, and new to the Council, perhaps you’re struggling to understand the depth of relationships that some of us had with our beloved Chancellor.” Credola Varina, the Theater-Guilder, was Bradomir’s cousin, and shared both his good looks and his supercilious attitude. Despite the circumstances, she’d found time to immaculately style her hair in a fashionable structure of braids, curls, and beaded sections. “I understand it possibly doesn’t mean as much to your family to be present, but some of us were very close.”

They continued to argue, always within the bounds of strict politenessbut voices growing shrill and honorifics delivered with increasing sarcasm as it escalated. Tain looked bewildered, his arms tucked across his chest and his eyes glazed. Jovan kept shooting concerned glances his way, sharing my worry that Tain was being talked over by his own Council. These early days would be critical for his reign. He was at least ten years younger than the nearest Councilor in age, and his fluctuating interest in his duties as Heir had taught the rest of them to disregard him. If he didn’t assert himself, that would set the pattern for his leadership.

Then he surprised me, and every one else in the room, with a sudden bang on the table as he brought down his fist. “We’re not delaying the funeral. The Scribe-Guilder will prioritize which messengers are sent where. Next issue?”

Everyone stared. Bradomir stroked his moustache, his eyes cold and evaluating. Credola Nara scowled, her bitter slash of a mouth working as if restraining the urge to criticize an impertinent child. I thought I glimpsed the acting Warrior-Guilder, Marco, burying an approving smile. Budua,the elderly Scribe-Guilder, regarded him with pursed lips. One half of her deeply lined face from eye to chin bore a slight slump, the mark of a long-ago illness; the asymmetry made her resting expression as inscrutable as ever. “Of course, Honored Heir,” she murmured. “I think that—”

“With greatest respect, Honored Heir,” Bradomir interrupted smoothly, once again leaning in front of Jovan as if he were invisible, “that may be a mistake. There are many important people who will need to travel for the funeral. I am aware that custom is to hold it within three days, but only for outdated religious reasons. In our modern times, few would object to a sensible delay for reasons of state.”

“My uncle may not have been a religious man, but he was a great believer in custom and tradition,” Tain said. “Every Chancellor since we built this city has been buried in the Bright Lake. I don’t think he’d have wanted an accident at the cote to delay an important ritual. The city will be in mourning until we farewell the Chancellor properly. Do you expect every merchant in the city to stop business for weeks while we wait for our relatives to arrive?”

“But—”

“Next issue, please,” Tain said.

I winced. Bradomir’s family was one of the richest and most honored of the Credol Families and easier to manage as an ally than an enemy, regardless of his difficult personality. Tain needed to assert himself, but he didn’t need to be combative.

“Is anyone going to tell us the risk of this illness, whatever it is, spreading to half the city?” Credola Nara asked, not bothering to wait to be invited to speak. “And what’s being done about this Talafan fellow?”

Tain rubbed his forehead, looking drained. “The hospital cleared everyone else who touched the animal. Whatever it was seems to have died with the creature. As for Lord Ectar, he’s our guest at the moment.”

“Lock him up! You can’t trust those Talafan. Probably here on the Emperor’s orders.”

“Now, now, Credola,” Bradomir said. “The Honored Heir has said there is no indication—”

“They’ve been complaining about paying our duties for years. Whingeing, cunning bastards. They’d cut us out of the equation altogether if they could, I’ll give you the drum.”

“No doubt this animosity has nothing to do with your business competing with the Empire, Credola,” Javesto said, eyebrows raised. “Just a coincidence,I’m sure.”

I adjusted, trying to restore blood flow to my lower legs and beginning to regret my impulse to use the spyhole. Transparent self-interest seemed to be the only thing motivating the childish squabbles below. Perhaps we were being paranoid.

“We’ll have a report from the hospital after they’ve… after they’ve finished examining the bodies,” Tain said. “We’ll know more then. For now, there’s nothing much we can do.” He looked around the table. “Is there anything else pressing that needs to be discussed today?”

Eliska, the Stone-Guilder, cleared her throat, twirling her simple necklace between nervous fingers. In her forties, she was one of the youngest Councilors. Her tone and expression were tentative. “If I may, Honored Heir? I know this is not an important matter by comparison, but you may not have heard that we’ve been having trouble with harvest and other deliveries failing to arrive to the city in the past few weeks. I believe a number of the Credol Families’ stewards have sent word that deliveries have left the estates, but they’ve yet to arrive. While no one has reported trouble on the main roads at the gates, I’m concerned that there may be bandit activity on the estate tributary roads.”

A few heads nodded around both sides of the table. Etan had been investigating that very thing on the day he died. Clearly our own deliveries weren’t the only ones that had been affected.

Marco cleared his throat. When he spoke, his soft voice came out a gentle contrast to his grizzled exterior. His foreign background was more apparent in his physical appearance than in his faint western accent. “I could send some men out to look into it, Honored Heir, but with the army away, we have a very limited garrison in the city.”

“Well, what about sending some Order Guards, then?” Credo Javesto asked. “Surely they can deal with bandits if that’s the problem.”

Marco’s visible uncertainty increased. “Silasta does not maintain the army at full readiness all the time,” he said. “We could not afford to. Our soldiers have ordinary jobs in the city and one of the most common occupations is Order Guard. When the Council sent the full army away, most of our Order Guards were required to go with it, as soldiers.

“Rather than send Order Guards we need here, if the Council agrees, I could send word to Warrior-Guilder Aven and ask her to siphon off a small force to investigate. The army is south near the spice mines, not too far from Moncasta or the Ash estate. When we inform the Warrior-Guilder of the death of—of the tragic news, we could also ask the army to send a force to check the roads and surrounding countryside.”

Credola Nara, head of the Ash family, gave an indignant snort and exchanged a look with the Craft-Guilder, her nephew Pedrag. “No bandits on my estates. My steward runs a tight operation out there. She’d know about it if there were trouble on my roads.”

“Not if messages are being intercepted or delayed on those very roads, my dear Credola,” Credo Javesto said. “That’s rather the point.”

Jov’s fingers tightened in sequence. This was his first Council meeting, and he must be hating the assessing gaze of all those men and women. “What about the safety of our messengers to the estates, then?” he asked. “If there might be bandits preying on the roads, do we need to send anOrder Guard with each courier for protection?”

“I do not know if we have sufficient Guards in the city to spare so many,” Marco said with a frown. “We will still need to keep the peace in the interim.”

Budua, the Scribe-Guilder, was the formidable stick insect queen of my own Administrative Guild, but she had once been a teacher and it still showed; she might even have taught some of the men and women around this very table. The ailment that affected the right half of her body had not noticeably limited her movements or her charisma. When she rapped a bony hand lightly on the table, the whole Council snapped to attention. “Since the safety of the couriers is my responsibility as their Guilder, it is my opinion that they should be adequately protected. It would only be fora few days.”

“I agree,” said Bradomir. “Our city—and ourselves, of course—may be in mourning, but we cannot neglect our duty to keep our own roads safe, not when our country’s reputation is built on safe trade.”

“While you’re sending messengers to your steward, you just make sure she’s not burning that south field we spoke about.” Nara pointed a thin finger at Javesto. “I could swear I saw smoke on the horizon in that direction this morning, and we agreed that would have to wait until all the summer winds were past. If that smoke affects the taste of my kori crop this year you’ll be hearing about it.”

“Smoke? I don’t think so. If you’re having trouble with your eyesight again, Credola, there’s a very fine spectacle shop not far from your house. I’d be well pleased to escort you.”

I stifled a yawn as they continued, once again the Families dominating the conversation while the Guilders held back. Even the two Guilders who were also Credolen—Varina and Pedrag—had earned their positions on merit, and had less to gain from the scramble for position and influence than the Families, whose relative honor and status might shift depending on their relationship with the new Chancellor.

The new Chancellor. The reality of it pressed like an expanding stone in my chest.

As though connecting to my thought, the meeting below drew to its most important conclusion. His handsome face grave, Credo Bradomir sat up straighter. “Honored colleagues, there is of course one more matter to address today. Tradition dictates that we formalize our new Chancellor before we farewell our former.” His voice dropped, becoming gentler, solicitous. “But this has been a terrible shock to us. The Honored Heir has not had sufficient time to prepare for his ascension. I, for one,would be happy to support a longer transition period, if this Honored Council is so generous.” He smiled at Tain, a benevolent elder offering a gift.

“Of course,” Varina jumped in immediately. “It’s only sensible.”

“Yes, yes, a fair point,” Javesto agreed.

“Indeed, indeed,” said Pedrag.

Nara hesitated a moment, her skeletal face twitching as she attempted warmth. “That sounds reasonable to me.”

The stone in my chest pressed harder. A tiny hint of weakness and they were circling. Tain wore the same wide-eyed expression as last time they’d talked over him; Jov looked doubly tense as his eyes flicked around at all the Councilors, but he stayed silent. Had he forgotten he was no longer an observer, but a voice in the Council on his own?

The lowborn Guilders mostly sat in cynical silence—a delay in formally elevating Tain to Chancellor didn’t affect them one way or the other, but they weren’t oblivious to the opportunities it afforded the Credol Families. Marco, though, cleared his throat, looking uncomfortable. “Forgive me, honorable Councilors. Perhaps I do not understand this issue. Was the Heir not presented by the Chancellor and endorsed by the Council years ago? Unless there is to be a new vote, what gain is there in waiting?”

Uncomfortable silence fell. Bradomir continued to stroke his moustache, but a vein in his neck pulsed as he stared at the Warrior-Guilder. Jovan, on the other hand, gave Marco a look that suggested he’d rather like to hug him.

“Of course nobody is suggesting a vote,” said Credo Lazar, whose presence I’d almost forgotten due to his uncharacteristic reticence. “Honored Heir, I stand ready to advise and guide you as you lead us into your most honorable reign.”

Once a few Councilors had echoed the sentiment, they all followed in turn, falling over themselves to offer support; if they couldn’t supplant Tain, they’d seek to make him reliant on them instead. But I didn’t miss the cold calculation in Bradomir’s eyes, or the naked resentment in Nara’s, as they watched their new leader. It was stuffy up in my perch, and far too hot. I shivered all the same.

* * *

The day passed in a kind of busy tedium. Jovan and I both avoided our empty, quiet apartments, where the absence of Etan was most apparent. I crafted a message for Mother and our steward, our third cousin Alozia, in the buzzing anonymity of the Administrative Guildhall, wondering as I did how they would react to the news. Mother and Etan had had such a complicated relationship, brittle from the strain of their mirrored resentments, yet deeply moored in shared respect and history. The extended family, too, would feel the strain not only of the loss of their ceremonial head, but the knowledge that one of the younger generation would need to come to the city to be Jov’s apprentice. Every one had assumed I would provide him with an heir in time, but no one had expected him to need one so soon.

Just what I needed; another reminder of my limitations. Unconsciously, my hands pressed against my abdomen. I could find a willing partner in the curtain rooms of the bathhouses as easily as anyone, but Thendra had warned me that pregnancy would be dangerous and likely unsuccessful. Perhaps it was for the best that one of our cousins’ children move to our apartments and take my child’s role.

I finished the letter and left it with the assigned messengers. Our family would never make it back for the funeral— it’d be over before they even got the message, prob ably—but they’d have time to prepare for Jovan and me to return home with Etan’s body, at least.

And, it transpired, part of the reason Tain had insisted on pressing ahead with the funeral was to avoid families returning in time. “He didn’t want to have to deal with his mother,” Jov told me when we met later. “He wasn’t sure which would be worse—her turning up or her staying behind.”

“I’m sure she would have wanted to see Tain,” I said. “And wouldn’t his brothers and sisters have come, too?”

He shrugged. “She made her decision a long time ago. Coming back now, it’d bring the whole thing up again.”

I’d only been ten or so, but it was impossible to forget the intensity of the scandal when Credola Casimira, Tain’s mother and the Chancellor’s only sister, had left Caslav and her eldest son to abscond with a romantic partner,a man of another family. The dishonor to Caslav, and the stain she had left on the remainder of her children by raising them outside the reputation, safety, and security of their own family unit, echoed through society even now. Still, I knew enough about foreign societies and their different conceptions of family to understand Casimira, at least a bit.

“She was in love,” I couldn’t resist pointing out. “Can’t people forgive her for that?”

My brother looked genuinely baffled. “What’s romantic love got to do with family? Casimira abandoned her family and honor, and she cost Tain his siblings. No one would accept them here, when they’ve been raised without a Tashi and without honor.”

“Shh,” I quieted him, as Tain appeared from within the passing crowd.

He had covered his tattoos and was unaccompanied by servants. Not wanting to draw attention, we kept to the busiest streets, sharing the bread Jovan had brought from our own kitchens. Thendra had promised a report by this afternoon, and I doubted any of us would be able to think of much else until we heard what she’d learned from her examination. Our nondescript clothing and hidden family markings seemed to work, because on Red Fern Avenue even Marco walked past, in conversation with two Order Guards, without noticing us. We were almost at the hospital when Jovan touched Tain’s shoulder and gestured behind us with a quick tilt of his head. “Someone recognized you.”

A man I did not know, middle-aged, not distinctive in any way, stood out from the crowd down the street only because of the directed intensity of his gaze. He moved toward us, lifting a hand in a kind of low wave, as if he meant to cry out for our attention.

“The petitioners are starting already,” Tain sighed. “I had to dodge a whole crowd of them getting out of the Manor. He’s going to have to wait, like every one else. Come on, before I get stuck.”

“Honored Heir!” Instead, the voice came from the other direction, and we spun to see Thendra, her tired face wearing a worried frown. “I would have brought you the report.” She ushered us into the hospital and into a private side room. At her instruction we wiped a waxy substance under our noses. My palms felt hot and sticky and my breath tight in my chest.

As ever, the physic wasted no time. “I do believe the creature and your uncles died of the same cause,” she said. “If you care to look?” She drew back a thin cloth. I squeezed my eyes shut and turned away, instinctively, at the flashed sight of layers of peeled-back skin and fur, and neat pilesof slimy organs. I did not care to look, as it turned out. I forced my eyes open but my stomach bucked in revulsion. Tain, looking equally horrified,squeezed my shoulder. Jov stepped closer.

“The stomach,” he said, and Thendra nodded, pressing into one of the gleaming white blobs beside the animal’s corpse.

“It had two stomachs. You can see the damage to the first, but not the second, yes?”

I leaned close enough to glimpse what looked like heavy corrosion of the pale stomach lining, then had to turn away again. The thought of this happening to my Tashi… My eyes burned again. I envied Jov’s dispassion.

“And my uncle?”

Thendra’s face froze, her gaze jumping to Tain and back again. We’d never have progressed beyond primitive medicine without internal examinations of human corpses, but it was neither discussed openly, nor performed on the bodies of important citizens. Although the old religion was no longer commonly practiced in the cities, especially Silasta, death rituals remained an important part of our culture. Word could never get out that aCredo or, worse, the Chancellor himself, had been so desecrated. Jov gave her a wan smile. “He knows we gave you permission, Thendra,” he said.

“Credo Etan was one of the most learned minds in the city,” Tain said. “And he was the most honorable Councilor and adviser that my uncle could have asked for. He would have wanted us to use anything that could help protect us.”

She nodded stiffly. “I did examine Credo Etan, yes. Most respectfully.”

“Of course,” Jov murmured.

“I saw the same damage to his stomach and to part of his intestines, but also damage to his lungs and some other organs. I believe his heart failed, in the end.” She shook her head, looking back at the leksot’s stomach. “I would have expected complaints of abdominal pain,” she said. “The damage is most obvious in that area. There must have been some kind of numbing agent that prevented them from feeling the pain.”

“So what caused it? Was this a disease?”

Jov and Thendra exchanged looks. I wondered how much of our role she might have guessed. “No,” she said bluntly. “No, Honored Heir. The stomach is the area of greatest effect, and there was likewise some damage to the mouth and throat. There is no sign of corrosion in or around the scratches Credo Etan received from the creature. This was an ingested poison, consumed by both this animal and the Chancellor; of what kind, I do not know.”

Tain exhaled like he’d been struck. Jov merely nodded. I supposed I had known, too.

“Someone poisoned them.” From the dull resignation of his tone it was clear Tain had convinced himself it had been accidental. How much I had hoped the same.

Jov glanced at the dead animal then pointedly at me. His thoughts bled through his quick frown. My unease about the leksot’s placement in the garden, and the trampled feverhead, returned. Someone had deliberately poisoned the animal. To throw suspicion on a visiting noble, or Credo Lazar? Or in the hopes of disguising a murder as an accidental infection from an exotic pet?

“Thendra, did your apprentices help with the autopsy?” Tain asked suddenly.

“No, Honored Heir. Credo Jovan asked me to do this, but it is… unorthodox. I thought it best to—”

“Yes. Yes, it was best.” Tain squeezed his arms across his chest, tucking his hands into his armpits. His head made a little bobbing motion, like a constant affirmation of some inner thought. “Thendra, please promise me something.”

The physic gave a tense nod and regarded us, unblinking.

“Tell no one what you found. In your hospital records state only that you observed the leksot’s body and noted similar symptoms as Credo Etan and the Chancellor. Don’t tell anyone that you performed an internal examination, not of the animal and certainly not of Credo Etan. Just conclude it was likely the carrier of an exotic disease.”

We needed to know more. If whoever had poisoned the leksot believed we had been taken in by the ruse, we might have an advantage.

“Yes, Honored Heir,” Thendra said. “I understand. The city is reeling from this horrible tragedy, yes? It does not need to panic further.” She paused, a shake of her hands marking her transition from tension back to her usual gruff concern. “I must advise that you be careful, Honored Heir. If the Chancellor was indeed murdered…” She trailed off, but the unspoken end of the thought echoed around my head as if she had shouted it. Poison meant someone had targeted the Chancellor, with a poison Etan had failed to detect and we could not identify. Poison meant Tain could be targeted next.

And my brother with him.

* * *

The longhorn rolled out in grieving notes over the still lake, the sound racing across the water until it echoed into nothing on the far shore. Jovan stood in front of me, lined up with the other Councilors, his measured breathing punctuating the slower notes of the longhorn.

Earlier, Tain had performed the ceremonial release of Caslav’s body into the Bright Lake, to join his ancestors in their final rest. As the longhorns now played the traditional mourning music, he accepted personal condolences from those gathered as he moved down the line of Credolen and other prominent citizens. There only remained the final song, and then we could slip away. The public display of grief was part of our duties, of course, but oh, to be allowed to just take Etan and bury him in our homelands, instead of suffering through more scrutiny! Perhaps then we could say a proper goodbye to our Tashi, free of obligation and duty for at least a few days.

Just as Tain reached us, a commotion broke out down the shore. A messenger, right arm tattooed with the stylized pen of the Administrative Guild, same as my own, scurried toward us, his legs a frenzied staccato against his rigid body and bowed head. Every one stared. The entire city had been shutdown today for this ceremony; what could be important enough to interrupt it?

“Crowds are approaching the city from the west, Honored Heir— I mean to say, Honored Chancellor,” the messenger panted, voice low. “The guard at the west gate was afraid it was some kind of invading army, but she looked through the spyglass and it’s countryfolk. Peasants.”

“What do you mean, crowds?” Tain asked, picking up on the messenger’s undercurrent of unrest. The nearest Councilors edged closer to eavesdrop. The musicians playing the ceremonial music faltered and petered off.

“Hundreds of people. They’ve got something over their faces, wrapped around their heads.”

“Headscarves?” Jovan said, hesitant. Though rare in the cities, most countryfolk tied their hair with scarves because of the winds.

“More like masks, or veils, Credo.”

“Is it a religious thing? Lots of people in the country are still earthers.”

Jov looked over his shoulder to me for assistance, but I studied foreign cultures, not our own population. Earthers, a slang term for believers in the old Darfri religion, weren’t terribly common in the city, and less so in the higher classes; no one in our family or any of the other prominent Silastian families had been religious in generations, that I knew of. Belief in spirits was generally regarded as an embarrassing relic of the past, unfit for a modern and civilized society. Still, we’d all been believers in the beginning;someone likely remembered more about the old rituals than I.

“May I ask what is happening, Honored Chancellor?” Bradomir sidled up, oily and obsequious.

Tain hesitated, glancing at the group of Councilors who had floated into hearing range like silent wraiths. One hand stole up to his upper arm, where bandages still covered the Chancellery tattoos. After a moment, he gestured to the messenger and the man repeated his news.

Marco snapped to immediate attention, shedding his shrunken demeanor. “Honored Chancellor, we need to secure the gates immediately until we know who or what is approaching.”

“It’s not an army, Warrior-Guilder, don’t worry,” Tain said. “That’s what the Guard thought at first, but it’s our own people. Farmers, estate folk.”

“But they’re wearing masks?” Varina, the Theater-Guilder, said. She stood too straight and spoke too loudly, with the exaggerated care of an intoxicated person trying to appear sober.

Another messenger, this one behind us, suddenly stepped through the gathering crowd and clarified. “Not masks. They’ve veiled their faces below the eyes, Honored Chancellor. And they’re coming from all directions, not just west. Across the plains and on the roads. They’re singing, we think. Can’t make it out, but old hymns, or something.”

“Our messengers obviously reached the estates, then,” said Credo Javesto. “I expect the workers have been given permission to stop work on their farms to show respect for the late Chancellor. I’ve seen a Darfri funeral before. I think they cover their faces as some kind of mourning ritual.”

Credo Bradomir whispered something to Credola Varina about Javesto’s upbringing; I didn’t hear it properly but the scornful tone was clear enough. He’d spent some of his childhood on his family’s estates rather than in Silasta, and no amount of expensive city living could erase that humble past in the eyes of some of his colleagues. He was also very new to the Council, only recently having taken his great-aunt’s seat.

“Peasants don’t respect anything.” Credola Nara’s tone was acidic as always. “They don’t even understand honor. Prob ably just want a day off work.”

“You know, I can’t imagine why workers on your land don’t respect you. It’s a real mystery, Credola.” Javesto turned to Tain. “We should give word to open the gates for the crowds. Chancellor Caslav was their Chancellor, too, and they’ve just as much right to mourn as us.”

“My dear fellow, it’s a matter of practicality,” Bradomir said. “The gates to the city are shut today and must remain so. There is no room around the Bright Lake for thousands more mourners.”

As in Council, Tain’s vague bewilderment at the argument abruptly vanished; he cleared his throat aggressively until the cacophony quieted. “We’ll finish the ceremony,” he said. “But afterwards, I’ll go out to the walls and personally thank our people for coming to honor my Tashi.”

Councilors exchanged calculating looks. The man they had regarded as a good-humored but somewhat irresponsible young relative rather than a player in Silastian politics was unpredictable, and forcing changes in their game.

Tain gestured to the musicians and the ceremony continued, culminating with us all singing along to the end of the mourning song. He left, head low, before the rest of us, but once we were free to move I followed Jov through the dispersing crowd to catch up with Tain as he headed west toward the city gate.

He caught sight of us. “I’m going to wait at the gate. Come with me? Unless you’re not finished doing whatever it is you’re doing.” The last was directed at my brother, who wore a frown of concentration and knotted his fingers tightly. “I can tell when you’re obsessing over something.”

“Hardly a brilliant insight,” I said. “You could say he was obsessing over something every couple of minutes and you’d be right most times.”

He grinned, if halfheartedly. “What’s the matter?”

Jov looked between us, his anxiety apparent. “Don’t you think this is odd? Yes, we sent messengers out, but every one just, what, dropped tools and started walking? How are they all arriving at the same time? It’s just… it’s odd, is all.”

I nodded. “It is. Are we absolutely sure that it’s actually our people? I’m still not sure about the veiling.”

“Maybe if we could hear what they were singing, as well,” Jov said. He stopped and looked over the small group of servants tailing us. “Are any of you believers? Or do you have family out in the country who are?”

All four servants shook their heads. “We were all born here in Silasta, Credo Jovan,” one said. “I’ve got distant family out in the Losi valley who’re prob ably earthers, but I don’t know much about it.”

We crossed Bell’s Bridge, following the main road through the lower city to the road gate in the outer west wall, a thick and imposing testament to a violent past that modern Silastians didn’t like to remember. A repetitive crunch of gravel from outside marked the grim shuffle of the people approaching on the road. Tain started up the external steps of the tower by the gate.

“I’m going to go up and see how far they are,” he said as he ascended. “If you can think of anything about Darfri mourning customs, any tips you could give me about something I can say, so I don’t accidentally insult some spirit or something, let me know. They’ve come all this way, I don’t want to look like an insensitive prick.”

Jovan leaned against the wall, closing his eyes. He might not have studied other cultures as I had but he had an amazing memory. He’d once tried to describe to me how he could take a familiar book off a shelf in his mind, recalling the feel of its pages, the smell of the ink, the illuminations and words. He’d read every book in the Manor and school libraries and, thanks to his compulsions, a lot of them more than once. Sometimes his obsessiveness could be an advantage.

Watching from the guard post as Tain made his way slowly up the tower was a strapping Order Guard with long braids. Her bicep was marked with the Warrior Guild’s knife, and her broad face wore a worried scowl.

“Ancient mourning practices,” Jov murmured, his eyes still closed, as if he were reading aloud from a book behind his eyes. “People used to—I mean I guess they still do, out there—think that death could be an offering to the spirits. Burying bodies near the person’s birthplace was about offering their essence back to the earth spirits. But there’s nothing about veiling as part of a funeral ritual.”

Jov opened his eyes. “Veiling, there was something about veiling I remember.…” His eyes widened. “Oh, shit. Tain!” he bellowed, scrambling up the steps.

A whistle and a high-pitched whine, then something made contact with the walls. The pale stone shuddered. I started after my brother, breath catching in my throat. “What’s happening?”

Tain, open-mouthed, burst through the tower door above. “They’re armed!” he yelled, disbelieving. “They’re attacking us!” Behind him, through the open tower door, the Order Guard tugged at the old bell pull, which labored and jerked under her strong grip.

Jov sprang up the last few steps and I followed, chest tight, to see the view for myself through the thin slit in the stone tower—rows and rows of eerie masked figures, stretching out beyond the walls in every direction. Bows in their hands revealed their intent. Not mourners but an army, marching straight toward us. Arrows struck the wall and the ground like pelting hail. After the volley, a roar drowned out the sound of the bell.

“They’re not mourning,” Jov said, breathless, as though the climb had been ten times as long. “Tain, it’s not veiling for mourning. Earthers veil for vengeance.”

As I watched, frozen by the sight—a scene that belonged in history books and tales of warring cultures, not assembled outside the walls of Silasta— the crowd released another volley. The weirdly attractive formation sailed toward us like a flock of pale, deadly birds. The Order Guard snapped down the shutter across the tower viewing slit.

All around us, the wheezy old bell pealed out an alarm the city hadn’t heard in living memory.

Paralysis lifting, I grabbed Tain’s shoulder, shaking him out of a similar stupor. “We have to get back to the city,” I said. Beside me, Jov twitched madly, his hands spasming. By my reckoning, this time, it was the right situation for some good old-fashioned panic. “Come on!”

“Keep the bell going and stay safe,” Tain told the Order Guard. She nodded grimly, drawing her sword—useless against an army outside a massive thirty-tread wall—and continuing to ring the bell with her free hand.

We half-ran, half-slid down the steps.

“We’ve got to let every one know what’s going on, and get you away from these damn walls,” Jov said.

“What did you mean, vengeance?” Tain looked confused. “For my Tashi? Who do they want revenge on?”

Jov shook his head, shuddering. “I don’t know. But it’s about justice. There was a picture—I remember the picture. A beaten man, and relatives surrounding him, with spears, and their faces veiled below the eyes. Spearing the attacker. Skewering him.”

“Honored Chancellor!” A group of three Order Guards met us. They clasped their hands together and raised the grip to Tain in respect. Silence fell as we looked at each other. I barely knew what to say or think. Jov looked on the brink of a meltdown, his hands and thigh muscles tightening and loosening and his face losing color. I put a hand on his shoulders, hoping to calm him, but he jolted under the touch and moved away.

“Tain,” he said, his voice choking out. “Tain, the army.”

And only then did true dread seize me, too, as I remembered where our actual army was.

“I’ll send a bird—” I started to say, then fell into silence, meeting Jov’s horrified expression. No birds to send, and clearly no accident.

Tain didn’t blink. “All right,” he said, scanning the gathered group.“We need to get organized. There’s a force out there, and they’re coming in fast. How many of you are there in the city?”

Silence. I remembered what Marco had said in the meeting: most of the Order Guards were in the army, leaving us under-garrisoned. The guard in front looked young and frightened beneath his shining helmet. I didn’t blame him. Order Guards kept peace and order within the city; they dealt with the occasional unruly crowd or un-Guilded street seller, carried the odd drunk tourist back to their guesthouse. For those who weren’t already in the army, they prob ably never expected much more than that. Who would ever have expected to face an attack on the city itself?

Tain asked again, “How many?”

The man swallowed. “Twenty-two, Honored Chancellor,” he whispered.

“Twenty-two?”

We exchanged dull looks of horror. Not even two dozen Order Guards and a city full of civilians. And the army was upriver in the southern mountains, days away.

Excerpted from City of Lies, copyright © 2018 by Sam Hawke.