As the daughter of a rancher in 1840s Mexico, Nena knows a thing or two about monsters…

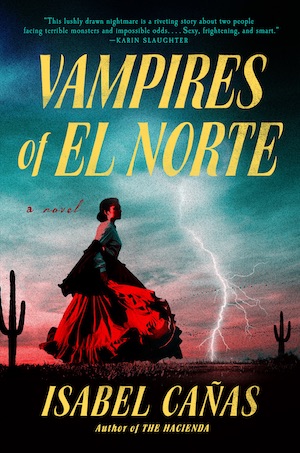

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Vampires of El Norte by Isabel Cañas, a genre-bending horror/western full of vampires and vaqueros—publishing with Berkley on August 15.

As the daughter of a rancher in 1840s Mexico, Nena knows a thing or two about monsters—her home has long been threatened by tensions with Anglo settlers from the north. But something more sinister lurks near the ranch at night, something that drains men of their blood and leaves them for dead.

Something that once attacked Nena nine years ago.

Believing Nena dead, Néstor has been on the run from his grief ever since, moving from ranch to ranch working as a vaquero. But no amount of drink can dispel the night terrors of sharp teeth; no woman can erase his childhood sweetheart from his mind.

When the United States invades Mexico in 1846, the two are brought abruptly together on the road to war: Nena as a curandera, a healer striving to prove her worth to her father so that he does not marry her off to a stranger, and Néstor as a member of the auxiliary cavalry of ranchers and vaqueros. But the shock of their reunion—and Nena’s rage at Néstor for seemingly abandoning her long ago—is quickly overshadowed by the appearance of a nightmare made flesh.

And unless Nena and Néstor work through their past and face the future together, neither will survive to see the dawn.

Humid tendrils of mist pawed at Nena’s skirts as she crossed the central rancho, the bag of her curandera’s supplies beating an urgent rhythm against one thigh. She strode through cold, dewy grass toward the vaquero Ignacio’s jacal, her breath coming short from haste.

Buy the Book

Vampires of El Norte

Yesterday, Abuela’s hands clicked and curled inward from the damp. The promise of a storm stiffened her joints; her movements became slower than usual, restricted by pain. Nena put warm compresses on Abuela’s hands and promised that she was capable of taking on any ailments that might strike the people of the rancho—God forbid—while Abuela rested.

So when a young vaquero pounded on the door of la casa mayor as madrugada lightened, asking for a curandera, Nena had risen and snatched the first work clothes she set eyes on. As she left the house, she made sure to meet eyes with Papá and give him a curt nod. Though his expression was bleary from being woken suddenly, she prayed that he recognized how important her task was: her presence was integral for the strength of the rancho. Necessary. Especially as Abuela grew older.

The rancho was a lively beast with many limbs; lately, she fretted about it. It was tired, stretched thin, its strength paled by sickness at the worst possible time. They could not afford weakness when Anglos breathed down their necks. So she would tend to it with every technique she knew, and would not rest until it was well again.

She reached the high walls that enclosed the rancho’s most precious organs like curving wooden ribs and passed through the gate, leaving it to creak shut behind her.

Metal scraped over metal; the gate’s latch clicked into place with a tone of finality.

Stillness hung with the mist over the rest of the rancho.

She should hear crickets. At this hour, she should hear the trill of birds.

Everything was as it should be on a March morning in the hours before dawn. Everything smelled as it always had.

But for some reason, she felt as if she were suspended in a pocket of silence between the central rancho and the jacales, silence broken only by the swish of her skirts in the chill, damp grass. The soft crush of the soles of her boots, now hesitant, on the earth.

Her own breathing.

The more she noticed this, the more her breath pulled raspy. The louder and farther it seemed to stretch through the mist. The faster she sought breath after breath.

She cast a glance over her shoulder.

Behind her: mist curled between her and the walls of the central rancho. To her left: a sea of fog sheathed the dark line of oak trees on the way to the springs.

A longing for a torch flared sudden and urgent in her breast.

That was odd for her, someone who happily snuck outside to her herb garden after moonset to be alone beneath the stars.

It was odd that she should feel as if something was observing her.

Along the dark line of trees, a shadow shifted.

She shied sideways, boots scuffing the dirt, nearly stumbling as she righted herself. Her heart leaped to a gallop. A hot, itchy prickling spread over the skin above her right collarbone, right over her scar.

She scanned the trees, rubbing a hand over the rippled skin at her neck. Her palm rolled over the chain of her scapular, grounding her. That must have been a deer. So where was it now?

She saw nothing.

And yet, a sensation lifted on the back of her neck, cloyingly soft as the legs of insects, that she was being watched.

That she should run.

But there was nothing there.

She inhaled sharply through her nose and set off toward the vaqueros’ jacales at a brisk, determined pace, rubbing her scar to dismiss the prickling sensation. She ignored the creeping on the back of her neck. The messenger who pounded on the door of la casa mayor said Ignacio had suffered susto. Haste was of the essence. Now was not the time to let the mist play tricks on her.

The sloping roofs of jacales sharpened through the mist as she grew close to Ignacio’s home. They slumbered like dogs curled around a fire, but not for long. Within a short time, before sunrise, vaqueros, pastores, and farmworkers would rise for the day’s work. The rancho would twitch and stretch, yawning and rising to sniff out the news: was the young curandera successful at curing Ignacio or not?

But for now, the only sign of life stood on the patio of Ignacio’s jacal. The dark hair of his wife, Elena, hung in sleep-loosened plaits over her shoulders. The closer Nena drew to the patio, the more evident the worry and grief on Elena’s face was.

Elena was two years younger than her; they had known each other their whole lives on the rancho, listening to Abuela’s ghost stories together around the fire at Nochebuena, feeding the chickens every morning until they were old and strong enough to help carry water from the springs to the house. Now, Elena was married and—judging from her recent and persistent requests for ginger to combat nausea—was with child. Worry weighed on the gentle slope of her shoulders as she looked past Nena.

“Where is Abuela?” she asked, voice high and strained with anxiety.

“She’s ill,” Nena replied. She nodded at the mist. “It’s the damp. She will recover when the rain breaks and passes, but for now…” A cloud passed over Elena’s face. Nena knew that look well: it was a flicker of doubt about Nena. It struck like a stone flung against her shoulder, but she pushed the hurt aside. Whatever state Ignacio was in, she had to be able to heal him. She had to. Elena would never trust her as a curandera otherwise. Neither would anyone else.

“Come in,” Elena said, and turned to the door.

Nena cast one final look over her shoulder at the mist, at the dark line of trees, then followed Elena into the jacal.

But behind Nena’s turned back, something shifted through the fog. A dark shadow moved, fluid as spirit, from one tree to the next.

Excerpted from Vampires of El Norte by Isabel Cañas, published by Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Isabel Cañas.