Cent can teleport. So can her parents, but they are the only people in the world who can. This is not as great as you might think it would be—sure, you can go shopping in Japan and then have tea in London, but it’s hard to keep a secret like that. And there are people, dangerous people, who work for governments and have guns, who want to make you do just this one thing for them. And when you’re a teenage girl things get even more complicated. High school. Boys. Global climate change, refugees, and genocide. Orbital mechanics.

But Cent isn’t easily daunted, and neither are Davy and Millie, her parents. She’s going to make some changes in the world.

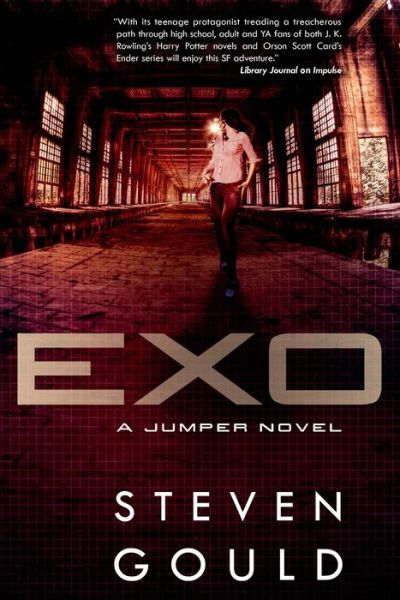

Steven Gould returns to the world of his classic novel Jumper in Exo, the sequel to Impulse, blending the drama of high school with world shattering consequences. Exo publishes September 9th from Tor Books!

ONE

I was breathing pure oxygen through a full face mask and the rest of my body was covered in heavily insulated hooded coveralls, gloves, and boots. The electronic thermometer strapped around my right sleeve read forty-five degrees below zero. The aviation GPS strapped to my left arm read forty-five thousand feet above sea level. I was three miles higher than Everest.

The curvature of the earth was pronounced, and though the sun was out, the sky was only blue at the horizon, fading to deep blue and then black overhead.

There were stars.

The air was thin.

I was dropping.

I reached two hundred miles per hour within seconds, but I didn’t want to go down yet. I jumped back to forty-five thousand feet and loitered, falling and returning, never letting myself fall more than a few seconds. But then the mask fogged, then frosted, and I felt a stinging on my wrist and a wave of dizziness.

I jumped away, appearing twenty-five thousand feet lower, in warmer and thicker air. I let myself fall, working my jaw vigorously to equalize the pressure in my inner ears.

Jumping directly back to ground level would probably have burst my eardrums.

With the air pulling at my clothes and shrieking past my helmet, I watched the GPS’s altimeter reading flash down through the numbers. When it blurred past ten thousand feet, I took a deep breath and jumped home to the cabin in the Yukon.

“Looks like frostbite,” Mom said two days later.

I had a half-inch blister on the back of my right wrist and it was turning dark brown. “Will I lose my arm?”

Mom laughed. “I don’t think so. What were you doing?”

I shrugged. “Stuff.”

She stopped laughing. Mom could smell evasion at a hundred yards. “Antarctica?”

I thought about agreeing—it was winter down there, after all. “No, I was only nine miles away from the pit.”

“West Texas? It has to be in the nineties there, if not warmer.”

I pointed my finger up.

She looked at the ceiling, puzzled, then her mouth formed an “o” shape. “Nine miles. Straight up?”

“Well, nine miles above sea level.”

Mom’s mouth worked for a bit before she managed. “I trust you bundled up. Oxygen, too?”

“And I didn’t talk to strangers.” She was not amused.

“How are your ears?”

“Fine. I jumped up and down in stages. Deep breaths. No embolisms. No bends.”

Her eyes widened. “I didn’t realize bends was an issue. I thought the bends were a diving thing.”

Me and my big mouth.

“Uh, it can happen when you go to altitude.”

She waved her hand in a “go on” sort of way.

“Nitrogen bubbles form in the bloodstream when you drop the pressure faster than it can be offloaded by the lungs. So, yeah, it happens when you scuba dive deep, absorbing lots of nitrogen, and then come up too fast. But it can also happen by ascending to high altitude with normal nitrogen in your bloodstream.”

“How do you prevent it?”

“I prebreathe pure oxygen down on the ground, for forty-five minutes. It flushes out the nitrogen so it doesn’t form bubbles. No decompression sickness.”

I rubbed the skin around the blister. “But what I really need is a pressure suit.”

“Like a spacesuit?”

“Yes.”

Very like a spacesuit.

Dad showed up in my bedroom doorway before dinner.

“Are you trying to kill yourself?”

Someone (I’m looking at you, Mom) had clearly told him about the bit of frostbite on my wrist.

I raised my eyebrows.

He held up his hands and exhaled. After two breaths he said, “Starting over.” He paused a beat. “What are you trying to accomplish?”

I hadn’t talked about it, mainly because I knew Dad would wig out. But least he was making an effort. “For starters, LEO.”

“Low Earth orbit.” He took a deep breath and let it out. “I was afraid of that.” He sounded more resigned than anything.

I stared hard at his face and said, “You can’t say it’s an unworthy goal.”

He looked away, avoiding my eyes.

He was the one who’d jump me into the tall grass on the dunes, Cape Canaveral, at about T-minus-five minutes back when the shuttles were still operational. The night launches were my favorite.

His homeschool physics lessons used spacecraft velocities and accelerations. History work included manned space travel, and we worked the 1967 outer-space treaty into politics and law.

He helped me build and fire model rockets into the sky.

He sighed again. “I’d never say that,” Dad agreed. “I just want you to not die.”

Lately I wasn’t as concerned with that.

It even had its attraction.

It had only been one-and-a-half years, but both of us had changed.

I was a bit taller, a bit wider in the hips and chest, and it looked like I’d seen my last outbreak of acne vulgaris. I was more experienced. I was far less confident.

New Prospect, on the other hand, was the same size, but it wore natty fall colors. The aspens above town were a glorious gold, and along the streets the maples and oaks and elms ranged from red to yellow. The raking had started and bags waited at the sidewalk’s edge for the city compost pickup. I’d seen the town decked out before, but that was austere winter white, or the crusty grays of snow waiting too long for more snow or melting weather.

Main Street, though, hadn’t changed enough to be strange. It was full of memories, and when I saw the coffee shop the whole thing blurred out of focus and ran down my cheeks.

I had to take a moment.

The barista was new, not one from my time, and she served me with a friendly, yet impersonal, smile. I kept the hood of my sweatshirt forward, shadowing my face. The place was half full. It was Saturday afternoon, and though some of the patrons were young, they looked more like they went to the community college rather than Beckwourth High. I didn’t recognize any of them until I went up the stairs to the mezzanine.

I nearly jumped away.

When the lemon gets squeezed it’s hard on the lemon.

Instead I went to the table and pulled out my old chair and sat across from her.

She’d been reading and her face, when she looked up, went from irritation, to wide-eyed surprise, then, dammit, tears.

I leaned forward and put my hand over hers. “Shhhhh.”

Tara had also changed. When I’d first seen her, she bordered on anorexic, but the last time I saw her she was putting on healthy weight. Now she looked scary thin again, but it could be a growing spurt. She was taller than I remembered. At least she no longer hid herself beneath layers. She’s Diné on her mother’s side and Hispanic on her dad’s, though she never talked about him other than to say he was well out of her life.

It was so good to see her.

“Sorry, Cent,” she said after a moment.

I gestured toward the window with my free hand. “I just did the same thing on the sidewalk. I know why I did it. Why did you?”

It set her off again.

“Should you even be here?” she managed after a while.

I shrugged. “I missed the place.”

“Where are you going to school now?”

I grimaced. “Back to homeschooling. Sort of. Most of what I’m doing lately has been online, or I’ll audit a college course if the class size is big enough. I don’t register. How are you doing at Beckwourth?”

She shrugged. “Coasting. I’m taking marketing design and women’s studies at NPCC. That’s where my real effort is.” She tapped the book.

I read the chapter heading upside down, “The Social Construction of Gender.”

“And Jade?”

“She’s at Smith. Two thousand miles away.”

I nodded. I’d heard that from Joe. “You guys still, uh, together?”

The corners of her mouth hooked down. “As together as we can be from that distance.” She shook her head. “We text, we talk, we vid-chat on computer. We do homework together.” She glanced at her phone, lying on the table. “My phone would’ve beeped six times already if she weren’t in class. Her parents are taking her to Europe over Christmas break. I think her mother is doing it deliberately, so Jade will have less time with me.”

“Really?”

She shook her head violently. “I’m probably just me being paranoid. It’s the opportunity of a lifetime, you know? Jade swears that they’re okay with us. Or at least they’re resigned. But she’s not coming home for Thanksgiving. They could afford it, but her mom arranged for her to spend the break with some East Coast relatives—distant relatives. I won’t see Jade until the third week in January.”

Ouch.

“Enough about my shit,” Tara said. “Are you seeing anybody?”

I had to look away. I felt the same expression on my face that I’d seen on hers. Then I told her what I hadn’t even told my parents. “I was. No longer.”

“Oh,” she said, quietly. “Sorry.” Then she quoted me, from the first day I’d met her: “So I’m unsocialized and very likely to say the wrong thing. Just want you to know I was raised in a box, right? I’m not trying to be mean—I’m just stupid that way.”

It worked. I smiled. “I know. Muy estúpido.”

She hit me. “You want to talk about it?”

I shook my head. “A little too fresh, you know?”

She nodded. “Oh, yeah. I know.” She gave me a moment, sipping at her drink. “So, are you going to be around? Or is this just a quick check-in, with you disappearing for another year or two?”

I hadn’t thought about it. Mostly I just wanted to see the place. It was probably the breakup. It brought back memories of all those places where things had started, but I realized how good it was to see her.

“I missed you guys. I’d like to keep in contact, without being stupid. Remember what happened to you and Jade when you hung out with me before?”

“You didn’t do that.”

“Yeah, but if you hadn’t been hanging with me—”

“I wish you could hang out with both of us. It would mean Jade and I were in the same place.”

“Ah. Well, right.” I said. “Maybe I can help with that.”

I can’t jump to someplace I’ve never been. The exception is jumping to a place I can see from where I am: to the other side of a windowed door; to a ledge up a cliff; to the other side of persons facing me. I’ve jumped as far as a half mile using binoculars to pick my destination.

But I’d never been to Northampton, Massachusetts, where Smith College was. The closest I’d been was New York City or Boston. I could’ve jumped to one of those cities and taken a train or a bus. Or I could’ve flown into Bradley International near Hartford, Connecticut, but going into airports was something we avoided unless there was no choice.

I stepped out from between two trees against a wrought iron fence in Washington Square. I was overwarm even though the insulated overall I wore was off my shoulders, the arms tied around my waist and its hood was hanging down over my butt. It was only slightly cool here. People walked by in light jackets or pullovers. The leaves were starting to turn here, too, but it was the beginning of the change, with many trees still green and very few fallen leaves.

The sun had set twenty minutes before, but the sky was still lit, and, of course, it was New York City, so it never really got dark. One way or another, barring power outages, it would stay brightly lit until sunrise.

And that would never do for my next trick.

I caught a half-full, uptown A train at the West 4th Street station, and rode standing, a grip on the vertical stanchion near the door. I put my earphones in and pretended to listen to music, but, as usual, when I’m en público, I people watch, and the earphones make them think I’m not listening.

A man, olive-skinned, light, trimmed beard, early thirties, well dressed in slacks, silk shirt, and a leather jacket, stepped up to me. He gestured at his own ears and said loudly, “Watcha listenin’ to?” He grabbed the same stanchion I was using, brushing against my hand.

I shifted my hand up the pole and leaned back. He was in my space. The subway car wasn’t that full.

He grinned and repeated himself, increasing the volume.

I sighed and took one earphone out. “Pardon?”

“Whatcha listenin’ to?”

“An audio book.”

He raised his eyebrows, prepared, I guess, to have opinions about music, but thrown by literature.

“Oh? What book?”

I looked around. There was an empty seat at the other end of the car between two big black guys, but they were sitting with their legs apart and their knees nearly touched, despite the empty seat between them.

“Must be a good book, yeah?”

I said, “Yes.”

“What’s it called?”

“Walden.”

“Huh. What’s it about?”

“It’s about someone who wants to be left alone.”

I put the earphone back in my ear.

He frowned, and then deliberately slid his hand up the stanchion. At the same time he swung around it, his free hand coming up behind me.

I let go and stepped away. “Hands to yourself!” I shouted. He flinched and the other passengers looked up.

“What the fuck are you talking about, girl?” he said.

“Get away from me!” I kept the volume up.

Mom told me that. When someone is acting inappropriately, don’t normalize it. Make it clear to everyone that you are not okay with the behavior. I’d seen her demonstrate it, once, when she and I were shopping in Tokyo. A man grabbed for her breast on the train. We’d had a long talk about it.

The asshole held his hands up, palm outward, and said, “You’re crazy, bitch.”

I walked around him and went down the other end of the car, standing by the two black guys. He followed, muttering angrily. I wasn’t worried about him. Worst-case scenario, I would just jump away, but he creeped me out.

The bigger of the two black men stood up and said, “Have a seat,” then stepped suddenly past me, blocking my friend with the boundary issues.

I sank down into hard plastic seat, watching, fascinated.

No words were exchanged, but the man in the silk and leather backpedaled, two quick steps, before he turned away and went back to the other end of the car.

The black man turned around and grabbed the stanchion. “You okay?” he said.

I nodded. “Thanks.”

He reached into his jacket and pulled out his phone. After going through a few menu choices he showed a photo to me. “My daughter. She’s at Columbia. On my way up to visit her.”

Oh. “Sophomore?” I said, smiling.

“Freshman. Engineering.”

She was tall, like him, probably a year older than me. “Isn’t it, like, really hard to get into Columbia?”

He nodded. The paternal pride was practically oozing out of his pores.

“She must be very smart.”

I wasn’t looking at the asshole directly, but I saw when he exited the car at Times Square.

I shook the hand of my protector when I got off at Columbus Circle, and this time, when I put my earphones on, I turned the music up.

By the time I’d wound my way into the middle of Central Park, dusk had gone to true night, and though there were some lights and the ever-present glow of the city all around, the woods gave patches of true darkness.

I was shrugging my way into the arms of my insulated overall when the man grabbed me from behind, one arm across my throat, the other hand pawing down my torso, starting at my breasts, then diving into the still unzipped front of the overall and trying to worm under the waistband of my jeans while he ground his hips against me.

I jumped in place, adding about thirty-feet-per-second velocity, straight up.

I instantly regretted it. As we shot into the air, the top of my head felt like I’d been struck with a two-by-four. I jumped back to the ground below.

My assailant kept going, briefly, topping out at around fifteen feet in the air before dropping again. My turn to backpedal. I took two quick steps away and felt his impact through the ground. He collapsed like a sack of potatoes, no flailing, no sound, and I wondered if I’d broken his neck when my head hit him.

I took out my cell phone and used the flashlight app to illuminate his face.

Olive-skinned, with a light, trimmed beard—the asshole from the train.

When he got off at Times Square, he must’ve stepped into a different car, then followed me from Columbus Circle.

I shook my head and turned off the damn music player. He’d never have gotten close if I hadn’t been blocking the ambient noise with earplugs.

Stupid!

His eyes were closed and his mouth was open and bleeding slightly, but he was breathing. I didn’t want to go too close, in case he was faking.

I rubbed the top of my head. There was a serious goose egg forming and it stung. When I examined my fingers with the light I saw a smear of blood on my fingertips.

I remembered his hand raking across my body and I had to resist the urge to kick him as he lay there.

He didn’t look poor. As I remembered, he wore gleaming loafers, slacks, a silk shirt under a leather jacket. He was wearing a fancy watch and two gold rings.

I slipped on my gloves and searched him.

His wallet held a driver’s license for one Vincent Daidone, four hundred dollars in cash, several credit cards in the same name, and three condoms. There was a baggy of white powder in his jacket pocket and an expensive phone in a silver protective case.

I looked at the picture and for a moment thought it couldn’t belong to the man on the ground. Something wasn’t right. Then I realized his face was swollen under his ears and his lower jaw was projecting forward, like a bad underbite.

His jaw’s dislocated, I realized. Or broken. I touched the bump on my head again. Lucky I hadn’t broken my neck.

I no longer felt like kicking him. I activated his phone. It was locked, but there was a button for calling an emergency number. I dialed 911.

“What is the nature of your emergency?”

“I’ve found an unconscious man, unresponsive, Central Park, in the trees behind the Dairy Visitor Center. He has some head trauma, but he is breathing and I’m not seeing any major bleeding. This is his phone. I’ll leave it on.”

“Who is speaking?”

I put the phone back in Mr. Daidone’s jacket pocket, careful not to hang up. The battery indicator showed three-quarters charged. I could hear the operator still talking, trying to get me to respond.

Mr. Daidone didn’t look like he had the financial need to rob, but perhaps that’s how he paid for his nice clothes. Still, I thought that his thing was more likely sexual assault, pure and simple. Not pure. Not simple. I hoped the white powder was drugs, but I wasn’t going to check any closer. I was still mad. I thought about taking the money, but instead I used my phone’s camera to take a close-up of his driver’s license, then put the wallet back in his pocket.

I walked away, to the Chess and Checkers House, jumping to the roof and crouching by the cupola in the center. It took the park police five minutes to respond, a car coming up East 65th. I watched their flashlights flickering through the trees for three minutes before they found him.

While I waited, I’d zipped up the coveralls, put on my goggles, and cinched the hood tight around my face. I’d only done this once before, in West Texas, as an experiment, but it had worked just fine.

I left the rooftop at 130 miles per hour, rising nearly a thousand feet before I slowed, then doing it again before I started changing the vector, adding horizontal velocity toward the northeast. I’d like to say that I shot into the air cleanly but, just like the first time I’d tried this, I tumbled wildly out of control the first few jumps.

At a 130 mph, the air feels like a wall, a palpable barrier that tears at you as you push your way though. It pulls at your clothes and snaps at your exposed skin. You want your shoes tied tight, and all your zippers secured. You want earplugs—or at least good flying music—because the air screams as it rips by.

Every time I tumbled, I jumped in place, changing my orientation, pointing my head to match the velocity vector. At these speeds the slightest movement of hand or leg, the crook of an elbow, the turn of the head, sends you spinning, and tumbling. You hold yourself semirigid. The more you relax, the more drag you have, but you can’t stay stiff as a board for too long, it’s exhausting.

You slow as you rise, but since you’re not rising straight up, you don’t come to a complete horizontal stop. There’s a moment when you feel yourself hang at the top of the parabola and then you’re falling again. At this time, I arch to a facedown free-fall position, then “cup” my arms and hands close to my body, steering. I’m tracking and, usually, I move a meter forward for every meter I fall.

I covered the length of the park in seconds, crossing the top of Manhattan, and then into the Bronx. I could see Long Island Sound to my right, a dark stretch between the lighted shores.

I had a GPS with a preset waypoint on my wrist and I would tweak the direction of my jumps. I was nervous about letting myself drop too far on the other end of the parabola, so I found myself rising higher and higher.

I knew I had to stay well above 854 feet, the highest hill anywhere near this route, but I soon found myself whistling along at five thousand feet and freezing my tuchus off.

It was exhilarating but tiring.

I’d checked the driving distance online, and between Manhattan and Northampton was 157 miles of highway, but as the crow flies (or the Cent plummets) it was 126. But I was getting cold and the roar of the wind wore at me.

I endured. After all, I’d only have to do it once—for this location anyway.

The Connecticut River Valley and the I-91 corridor were easy to make out, but the GPS told me I was a bit south and that the mass of lights I’d pinned my hopes on was Holyoke, not Northampton. I followed the highway north.

Three more jumps and I was over Northampton, adjusting my speed until I stopped dead five thousand feet above a cluster of athletic fields by Paradise Pond, my chosen waypoint.

Gravity took over and I fell, face down, my eyes flicking back and forth from the altimeter readout to the green grass below.

At a thousand feet I killed my downward velocity, then dropped again, never letting myself drop more than three seconds before stopping my downward velocity again.

At thirty feet, I jumped to the ground and fell over.

I thought I was just tired. The passage through the air had been like being pummeled with socks filled with dirt, and my body was stiff from the wind and stiff from holding low-drag positions for extended periods of time. Still, when I came down into the kitchen after returning to the cabin, Mom took one look at my face and said, “What happened?”

I blinked. “Huh?”

“You looked angry just then. Did your father do something?” I shook my head. Angry?

Then I remembered the hand pawing across my front and the hips pushing at me.

“You are angry about something.”

I nodded. “This guy grabbed me from behind in Central Park and groped me.”

Mom’s eyes widened and she looked closer at me, up and down. “Are you all right?”

I touched the top of my head. “Bit of a bump here.”

“He hit you?”

I shook my head. “I jumped up, like I do. Took him fifteen feet in the air, but my head—” I bumped my own chin from below with my fist. “—hit his jaw.”

“What happened to him?”

“Broke his jaw, or dislocated it. He was unconscious when I left. I called the police on his phone and backed off until they found him.”

“You could have just jumped away,” Mom said. “The other kind of jump.”

“He had his arm across my throat,” I said. “He might have come with me.” I sighed. “I didn’t even think about it, really. Just happened. At least this way he’s not likely to grab anyone else for a bit. Hopefully even longer than that. I think he had a Baggie of cocaine. At least he had a Baggie of white powder. Hopefully the police will bust him.”

Now that Mom had assured herself I was okay, she was getting angry. “They might not search him at all. After all, as far as they know, he’s a victim. Unless you told the police he’d attacked you.”

I shook my head. “No. I just described his injury and his location.”

“Did he just come out of the bushes or something?”

“He followed me. He tried to pick me up on the A train and when I was having none of it, he tried to grab my ass, but I yelled at him to keep his hands to himself. There were plenty of witnesses. I thought he got off the train at Times Square, but he must’ve gotten right back onto the next car. Then when I got off at Columbus Circle—” I shrugged. “It was my fault.”

“What?” Mom sounded really angry suddenly. “Honey, it was not your fault.”

I held up my hand. “Oh, no. Not my fault that he attacked me. I’m with you on that. He deserved everything he got, maybe more. It was careless of me, though. I put in my earphones and was listening to music. I don’t think he could’ve snuck up on me otherwise.”

Mom closed her eyes and took a deep breath, then let it out slowly. “Ah. I see. Yes, you should be careful. You know what your father would say it could’ve been—”

I finished the statement, making air quotes with my fingers, “—them.”

Mom nodded. “Yes. It could’ve been a loop of wire and a hypodermic.”

I nodded. “Yes. Believe me, I thought about that, too. I’ll be more careful.”

“You should tell your father about it.”

I winced. “Do I have to? You know how he’ll get.”

She raised her eyebrows. “Keep it brief. You don’t have to tell him about the earphones. Tell him about breaking the guy’s jaw—he’ll like that.”

She was right. When I described being attacked, Dad’s eyes narrowed and I could see his jaw muscles bunch as he ground his teeth together, but when I described the condition of the guy’s jaw and his fifteen-foot drop, he smiled.

But he also asked me to Bluetooth the picture of Mr. Daidone’s driver’s license from my phone to his.

“Just want to check on his status. Find out if they busted him for the coke or not. Whether he has priors, especially for sexual assault.”

“What are you going to do, Daddy, if he does have priors?”

“Not much. But I’ll know he’s probably not one of them.”

“One of them wouldn’t have priors?”

“If they did, they’d be made to go away, but really, their people don’t get caught in the first place. Not usually.”

“I thought you just wanted to make sure he paid, uh, for what he did.”

His face went still but there was a tic by his right cheekbone.

“Oh. You don’t approve of his behavior,” I ventured.

His eyes narrowed and for a moment, he seemed like someone else—someone a little scary. He pointed at me. “Just be careful, okay?” Then his face relaxed and he was back. “Speaking of that, let me see your wrist.”

I held up my left arm and he said, “Very funny,” so I peeled the Band-Aid back on my right wrist. The blister had popped a few days before and in its place was a swollen scab.

“It’s doing better,” I said, though, to be truthful, it looked a little worse than the blister had.

Dad made a noise in the back of his throat, but didn’t gainsay me. “So, what are you going to do? We could probably get a used Orlan suit on eBay, but it would probably be too big. Don’t think we’re gonna spend twelve million on a new NASA flightrated EMU.”

I shook my head. “I’ve been doing some research. There’s a team at MIT doing lots of work toward a Mars EVA suit, and this other guy in New Haven who just lost his funding.”

Dad rolled his eyes to the ceiling, then blew out through pursed lips. He glanced at my wrist again, and I covered the scab back up.

Finally he said, “Okay, give me the details.”

Jade came out of Hatfield Hall, where, according to Tara, her accelerated elementary French 101 class met. She was in a cluster of other girls and they were talking up a storm, but not English.

Some of their accents were clearly American and some reminded me of the streets of Paris. I tagged along behind the group, waiting for my opportunity. They moved toward the Campus Center, a thoroughly modern silver building totally at odds with the red brick nineteenth-century buildings all around.

Well before they got there, Jade said, “Au revoir,” and split off toward Elm Street.

From studying the map, I knew that Northrop House, her dormitory, was on the other side. I caught up with her as she waited for the light and said, “Comment allez-vous?”

She glanced sideways at me, and then jerked back, nearly stepping out into traffic.

“Cent?”

“Mais oui.”

“Wow. What are you doing here? Tara told me she’d seen you, but that was back at Krakatoa.” Unstated was the two thousand miles away.

I nodded. I hadn’t told Tara what I had in mind. I wasn’t sure it was a good idea myself, and I knew Dad wouldn’t think so. “Yeah. Tara really misses you.”

Jade sighed. “Yes.”

“You’ve got a walk signal,” I said, tilting my head toward the light.

“Oh. Right.” She didn’t say anything else until we’d crossed. “Are those people still after you, from before?”

I made a show of yawning. “Always.”

“Does that have anything to do with why you’re here at Smith?”

I shook my head. “No. I’m here for the same reason I saw Tara: to see how you’re doing.”

She reached out and touched my arm. “Okay—you really are here? Not my imagination?”

I hugged her and felt her stiffen, then clench me tightly. When I let go, her eyes were wet.

I smiled. “Maybe you have a really good imagination.”

“Come on up to my room. My roommate’s gone home to New Jersey for the weekend.”

“Sure.”

In her third-floor room, I sat on her desk chair and she sat cross-legged on her bed. The room wasn’t huge, but it was cozy. Her roommate was a bit of a slob but the mess stopped midway across the room, where a line of masking tape ran across the floor.

I glanced down at the line, my eyebrows raised.

“Yeah, she’s a bit of a pig, but she’s really nice. She just doesn’t care about, uh, being tidy. At the beginning of the semester we squabbled about it a little, but once I started moving her stuff back to her side of the room, she put the tape down and she’s really good about keeping her stuff on that side.

“Still, next year I can have a single room. I’m really looking forward to that.”

I asked her about her classes. It was only her first semester and she wouldn’t have to declare before the end of her sophomore year, but she was seriously considering international affairs and public policy.

“So you like it here?”

She nodded and starting crying.

Damn.

“Homesick?”

She nodded. “They’re different here. Everybody talks too fast and interrupts each other and you really have to be pushy to be heard in group discussions. And the food is bland.”

“Ah. No chile?”

“Not like home.”

In my time in New Prospect I hadn’t gotten used to the red and green chiles. Still, I understood.

“No friends?”

She shrugged. “My house is friendly enough, I guess.”

I pushed a little, “No special friends?”

She frowned at me then said, “What? I’m with Tara!”

I blew out a deep breath. Relief, I guess.

“Sorry,” I said. “Sometimes when people go away to college, they change. Long-distance relationships are really hard to maintain. Even when one person still wants the relationship, sometimes the other one…”

She was staring at me. “You aren’t talking about Tara and me, are you?”

It was my turn to tear up a bit. Unable to talk I just flipped my hand over, palm up.

Her cell phone chirped and she glanced down at it, read the screen, then smiled.

“Tara?” I managed.

“Yeah. She just got to the coffee shop.” There was a two hour time-zone difference. She lifted the phone again. “Wait until I tell her you’re here.”

I held up my hand, to keep her from texting.

“If I could bring Tara to you, right now, would you like to see her?”

“Not funny,” she said.

I jumped across the room to the window seat.

It was a good thing she was seated on the bed. She would’ve fallen off the chair.

“What the fuck?!”

She looked scared. I smiled, though I didn’t feel like it. “There’s a reason those people were, and will probably always be, after me and my parents.”

“What are you?!”

“Cent, remember?” I walked slowly back to the chair and sat down again. “I’m your friend. Just a girl who can do this extra thing.”

Her eyes were wide still, but her breathing slowed.

“So I meant it, when I asked if you’d like to see Tara.”

Tara was not surprised to see me but her eyes were wide when I walked up the stairs to the mezzanine of Krakatoa.

She held up her phone. “Jade just texted that I would see you in a moment. She’s got your number and I don’t?”

I shook my head. “She doesn’t have my number. Come on.”

“Come on? What’s up? Where are we going?” She pulled her backpack closer and slid her notebook into it.

There was no one else on the mezzanine. I let her stand and sling her backpack over one shoulder before I did it.

Tara screamed when she appeared in Jade’s room, and collapsed, but I was ready and eased her to the floor, and then Jade was there, clinging, and they were both crying.

I left the room the normal way and found the floor’s communal bathroom.

I stared in the mirror. The expression on my face was bleak.

I’d jumped into a different dorm room three weeks before.

Joe and I had been seeing each other only on the weekends—so he could get into the college groove properly—but I’d wanted him bad that night and I figured he could make an exception.

Apparently so did he, ’cause he wasn’t alone in his bed when I got there.

When I returned to Jade’s dorm room, I tapped gently before pushing the door open.

They were both sitting on the bed, side by side, no space between them. Both of them looked at me with large eyes.

“All right?” I said.

They looked at each other and involuntarily smiled, but when they looked back at me, their smiles faded.

“And they all moved away from me on the Group W bench,” I said. “Don’t make me sing. You won’t like me when I sing.”

Tara giggled and some of the tension went out of Jade’s posture.

“Let’s go get something to eat. I hear Northampton has great restaurants.”

They hesitated and I added, “Don’t make me hungry. You won’t like me when I’m hungry.”

And they both laughed and they stood and it was all right.

Exo © Steven Gould, 2014