In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work.

Sauron is one of Tolkien’s best-known and most terrifying villains. Fire and demons, darkness inescapable, and the pull of the Ring of Power surround him; he is often visualized (if incorrectly) as a great flaming Eye and, as a Lord of Middle-earth, stretches his power across the lands seeking again the One Ring. Many names are his, and yet he is the Nameless One. He is called Annatar, Zigūr, Thû, Gorthû, the Necromancer, Wizard, Magician, lieutenant of Morgoth, Lord of Wolves, King of Kings, Lord of the World. He is one of only a small handful of characters to play a significant part in tales of Arda from the creation of the universe through to the last of the tales of Middle-earth. At first he plays lackey, but with the ages his power increases and he rightly earns the title of Dark Lord from Morgoth, his master.

Sauron is unique for a number of reasons. Unlike many other of Tolkien’s creations, his conception remains relatively stable throughout the legendarium, and because of this he is also one of the few to experience complex and radical development across that same period. His journey from uncorrupted spirit to last of the great mythological evils to threaten Arda is therefore fascinating and worth a closer look.

We know from The Silmarillion that Sauron was a Maia and servant to Aulë the smith (20). Melkor and Aulë were ever in competition, and the fact that the former won over the greatest craftsman of the latter is significant. First of all, it seems to be a common theme for Tolkien. Consider, for example, Fëanor’s vacillation between the opposing influences of the two Vala and his wife Nerdanel’s specific commitment to Aulë. While Melkor is the personification of incorrect or immoral artistry and lurid possessiveness, Aulë is generous, open-hearted, and willing to submit his creations to the will of Ilúvatar. Melkor, and later Sauron, desire dominance; hence the One Ring, meant to bind in servitude the other Rings of Power. We know from the beginning, therefore, that Sauron is to be an artist who will ultimately choose to use his gifts for corrupt purposes.

Sauron’s fall is, however, of an altogether different kind than that of Melkor. Unlike his master, Sauron did not desire the annihilation of the world, but rather the sole possession of it (note how similarly Melkor corrupted Fëanor and Sauron). In fact, it was original Sauron’s virtue that drew him to Melkor: Tolkien writes that “he loved order and coordination, and disliked all confusion and wasteful friction. (It was the apparent will and power of Melkor to effect his designs quickly and masterfully that had first attracted Sauron to him)” (Morgoth’s Ring, hereafter MR, 396). Thus we can assume that in the beginning, Sauron was content with his participation in Ilúvatar’s Music: it was and remains the greatest example of creative participation in existence. Impatience and a tendency to be drawn in admiration by spirits more powerful and compelling than himself were his downfall. And indeed, as Tolkien notes, that tendency was but another perverted shadow of what was originally good: “the ability once in Sauron at least to admire or admit the superiority of a being other than himself” (MR 398)—a characteristic Melkor did not possess. It’s easy to see Sauron as the destructive Dark Lord of The Lord of the Rings, but Tolkien makes sure to emphasize that Sauron fell into the shadow of Melkor through the uncareful use of his virtues, not because he possessed some inherent flaw. Sauron was too quick to act, too fierce in his admiration of those greater than himself, and finally too devoted to order to notice that Melkor’s intentions were entirely egoistic and nihilistic (MR 396).

It’s only later, apparently, that Sauron truly falls into deception and wickedness. Offered a chance to repent and return to the circles of the Valar, Sauron refuses and escapes into hiding (MR 404). Before this, however, he works tirelessly as the chief captain of Melkor, now called Morgoth, and seems content in this position. It is Sauron who was, apparently, in charge of breeding and collecting Orcs for the armies of Morgoth, and for this reason he exerted greater control over them in his future endeavors than Morgoth himself (MR 419). At some point difficult to date, Sauron takes up residence at Tol-in-Gaurhoth, the Isle of Werewolves, where he is later met and defeated by Lúthien and Huan.

But before Sauron, the isle belonged to Tevildo, a demon in the physical form of a great cat, and it is this villain Lúthien meets when she comes flying from Doriath seeking her lover, Beren. Even at this point, and despite the cats, the germ of the later story is still apparent (The Book of Lost Tales 2, hereafter BLT2, 54). While the Nargothrond episode has not yet emerged, the contest between Huan and Tevildo foreshadows the struggles between Huan and Draugluin and wolf-Sauron. As Christopher Tolkien points out, though, it’s important not to assume that Tevildo became Sauron, or, in other words, that Sauron was once a cat (BLT2 53). Rather, Tevildo is merely a forerunner, and Sauron occupies the place in the narrative that Tevildo once held. But, as Christopher also notes, it’s not a simple replacement either, because many elements remain across the versions. After Tevildo is abandoned, Tolkien establishes the Lord of the Wolves, an “evil fay in beastlike shape,” on the isle. Finally, perhaps inevitably, Sauron takes the place of that apparition, and we’re given the tale of Lúthien’s assault on Tol-in-Gaurhoth in a relatively stable form.

Sauron’s first true defeat comes at the hands of Lúthien and Huan. The final story is slow to emerge, but eventually, we get the tale with which we’re so familiar. Lúthien, nearly despairing of finding Beren, comes with the help of Huan to Tol-in-Gaurhoth, and there sings a song of power that makes the isle tremble. Sauron sends out his beasts, but the hound of Valinor defeats each champion, even Draugluin the great wolf, until Sauron himself takes beast form and sallies out to meet his foe. But Huan seizes his throat without mercy, and though Sauron shifts shape many times he cannot escape. Lúthien then comes and commands Sauron to yield to her mastery of the isle; he does so, and when Huan releases him he takes the form of a great vampire and comes to Taur-nu-Fuin, the place where the warring powers of Melian and Sauron met and mingled in living horror (Sil 172-173).

Sauron continues to serve Morgoth up to the end: he’s put in command of Angband, and when the final battle is waged and Morgoth at last defeated, judged, and thrust through the Door of Night, it is to Angband that Sauron escapes, lurking in the shadows. His power only grows during this respite and he is looked upon as a god among the rough, untutored Men of Middle-earth.

At that time he took a fair form, seeming both wise and kind, and dwelt among the Elves. But this conception of Sauron only emerged for Tolkien when he wrote about Galadriel in The Lord of the Rings. In the early stages of drafting The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wasn’t sure how the Rings fit into the legendarium’s great scope. He toyed with various ideas. At one point it is Fëanor who forges the Rings (again suggesting a sort of artistic kinship of Fëanor and Sauron in Tolkien’s thought), and Sauron later steals them from the Elves (The Treason of Isengard, hereafter TI, 255). But despite some quibbling over their creation, Tolkien was clear early on that the Rings were possessed by Sauron—even in the very early drafts, when the Ring is but a trinket that can do minor harm, it is still the Ring of the Necromancer, and Sauron is repeatedly called the Lord of the Ring(s) (The Return of the Shadow, hereafter RS, 80, 81). In later drafts, and perhaps because of Sauron’s newly acquired title, Tolkien suggests that all the Rings of Power were originally created by Sauron (RS 404), and that they were many. In this case Sauron gains early fame as a generous lord, a ring-giver, whose realm is prosperous and whose people are content and wealthy (RS 258).

Only later does the conviction that only the One Ring was made by Sauron appear, and by the same token Tolkien becomes convinced that the elvish rings were unsullied and thus could be used in their own merit and for good by those who wielded them (TI 254, 259). (He also suggests that Galadriel mistrusted “Annatar,” or Lord of Gifts, as he called himself, from the beginning, but Christopher finds this somewhat problematic.)

Gradually the story of Sauron’s treachery as told in The Lord of the Rings develops. The Elves do not suspect him until, in his forge, he puts on the One Ring, and suddenly they become aware of him and his true purpose. They take the three elven rings and escape, but Sauron takes and corrupts the others, giving them to his servants as he sees fit.

His power only continues to increase, until at last the great kings of Númenor of the West hear of him. Ar-Pharazôn, a foolish ruler rejecting the idea that any king in Arda could be more powerful than himself, summons Sauron to Númenor in a move calculated to humiliate him. But he is deceived. Early drafts depicting Sauron’s coming are intense and leave no room for confusion. As the ship approaches the island a great wave, high as a mountain, lifts it up and casts it upon a high hill. Sauron disembarks and from there preaches, an image that recalls Christ’s sermon on the mount and establishes Sauron’s dominance. He offers a message of “deliverance from death,” and he “beguile[s] them with signs and wonders. And little by little they turned their hearts toward Morgoth, his master; and he prophesied that ere long he would come again into the world” (The Lost Road and Other Writings, hereafter LR, 29). He also preaches imperialism, telling the Númenoreans that the earth is theirs for the taking, goading them to conquer the leaderless rabble of Middle-earth (LR 74). He attempts to teach them a new language, which he claims is the true tongue they spoke before it was corrupted by the Elves (LR 75). His teaching ushers in an age of modern warfare in Númenor, leading “to the invention of ships of metal that traverse the seas without sails […]; to the building of grim fortresses and unlovely towers; and to missiles that pass with a noise like thunder to strike their targets many miles away” (LR 84). Sauron’s conquest of Númenor is bombastic, showy, and nearly instantaneous. He comes on them like a messiah from the depths of the Sea.

Buy the Book

Fate of the Fallen

The tale as it is told in The Silmarillion is far subtler. In that account, Sauron “humble[s] himself before Ar-Pharazôn and smooth[s] his tongue; and men [wonder], for all that he [says] seem[s] fair and wise” (Sil 279). Gradually he seduces the king and the people by playing on their fears and their malcontent, feeding them lies wrapped in truth until he has gained such a hold that he builds a temple to Morgoth and offers human sacrifices upon its altars. In The Silmarillion he is much more a cunning, silver-tongued flatterer who ensnares Ar-Pharazôn by pretending to impart a secret spiritual knowledge. The significance here is that even at this point in his journey to world-threatening power, Sauron still looks on Morgoth as his master or even as a god—or God. He still, as pointed out much earlier, is willing to acknowledge and even celebrate a power greater than himself.

When the climax comes and Númenor is overturned in the Sea, Sauron is stripped of his physical body and condemned to never again take on a fair form. He slinks back to Middle-earth and his Ring, takes up residence in Mordor, and continues to grow in power and influence. Eventually, as is now well known, he comes to such ascendancy that the great kings of Middle-earth, Elves and Men, band together in the Last Alliance and make war upon him. He is defeated when Isildur (first an elf and only later the son of Elendil), cuts the Ring from his finger. Elendil, before he dies, prophesies Sauron’s return with dark words (TI 129).

Sauron, stripped once again of his physical form, retreats to Dol Guldur in Mirkwood (which was originally in Mordor and also equated with Taur-nu-Fuin; see LR 317, RS 218), where he simmers malevolently while regaining his strength. The Ring, famously, passes out of knowledge when Isildur is killed while escaping Orcs.

The rest of the story is familiar, and interestingly, Sauron’s part in it undergoes little revision even while the rest of the narrative is in constant upheaval. A few details are different. At one point, Gandalf looks in the Stone of Orthanc and upon (presumably) encountering Sauron, tells the Dark Lord he’s too busy to talk—and “hangs up” (The War of the Ring, hereafter WR, 71-72). At another point, Tolkien planned to have Gandalf and Sauron parley together, suggesting that the Dark Lord would have to leave Mordor and appear in person and with dialogue—none of which he gets in the finished Lord of the Rings (indeed, the Dark Lord of the published narrative is glaringly absent, which makes his power all the more terrifying). In the original conception of Frodo’s temptation at the Cracks of Doom, Tolkien even toyed with the idea of having Sauron bargain with the hobbit, promising him (falsely, no doubt) a joint share in his rule if he turned over the Ring (RS 380). Other than these minor (and sometimes humorous) potential alternatives, however, the Sauron of The Lord of the Rings’s early drafts is the Sauron at the end of all things.

In all, Sauron’s character is remarkably consistent and coherent throughout the drafts, if we believe, as Christopher Tolkien assures us that we must, that Tevildo Prince of Cats is in no way Sauron himself (as Sauron existed as a distinct figure before Tevildo, this is undoubtedly correct). Sauron’s journey from an overeager, artistic Maia to Dark Lord and Nameless One illustrates several significant themes in Tolkien’s legendarium. First of all it insists, like Fëanor’s history, that improper uses of creativity and artistry, especially when combined with a possessive, domineering spirit, are irreparably corruptive. It also urges us to consider what Tolkien believed were the destructive effects of machines and, perhaps more specifically, mechanized thinking. “The world is not a machine that makes other machines after the fashion of Sauron,” Tolkien wrote in an abandoned draft of The Lost Road (LR 53). Sauron, who passionately desired order and perfect, rote production, had a mind of metal and gears, as was once said of Saruman. Sauron saw the beauty of a cooperation that naturally produces order (the Music), but instead of allowing an organic or creative participation to develop naturally, he became enamored of the kind of order that could be produced—enforced—by domination and tyranny. Sauron’s story is a warning. “‘Nothing is evil in the beginning,’” Elrond says, perhaps a trifle sadly. “‘Even Sauron was not so’” (LotR 267).

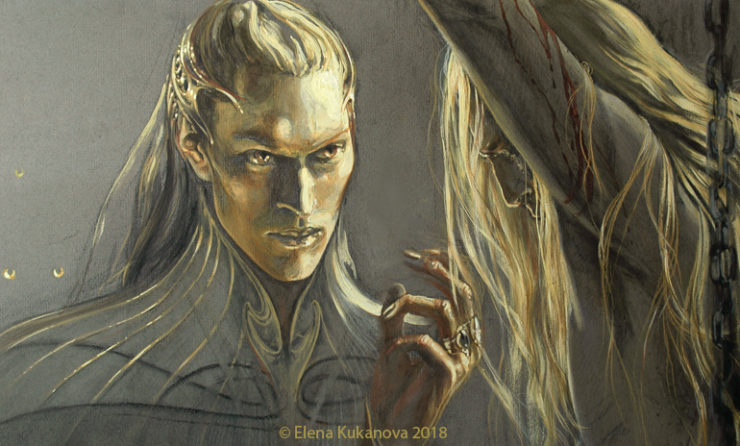

Top image: “The Temple of Melkor” by Elena Kukanova

Megan N. Fontenot is a hopelessly infatuated Tolkien fan and scholar, but she also studies Catholicism, eco-paganism, and ethno-nationalism in the long nineteenth century. And did she mention Tolkien? Give her a shoutout on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1!