In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Two of the greatest characters in fantasy fiction are Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, a pair of adventurers who are a study in contrasts, but still the best of friends and a remarkably effective team. Leiber’s tales about the duo appeared across an impressive four decades, with the later tales every bit as good as the early ones. The first of these stories was purchased back in 1939 by famed science fiction editor John Campbell—something that might surprise people who don’t realize Campbell also edited the short-lived fantasy magazine Unknown.

It’s no wonder that Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser are such popular characters. The world of fiction has always been enriched by tales of partnerships: two or more people working together can often be much more interesting than a solo hero. They have someone with whom they can talk, argue, collaborate, and fight with. Sometimes these partnerships are equal, while other relationships are between leader and sidekick. And the interactions between characters can be much more interesting, and revealing, than any internal monologue—think of Holmes and Watson; Kirk, Spock and McCoy; the Three Musketeers; Batman and Robin; Captain America and Bucky; Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Differences in personalities can add a lot of energy to a narrative, and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are as different as two people can be, with Fafhrd large but sensitive, and the Mouser skeptical and clever. The two adventurers also have weapons that mirror their respective personalities. Fafhrd’s sword is a massive two-handed claymore he dubs Graywand, and he is also skilled with other weapons. The Gray Mouser fights with a saber he calls Scalpel and a dagger called Cat’s Claw, and dabbles in a variety of magics, both light and dark.

The duo’s popularity has led to their appearances in comics, in games, and in the works of other authors, sometimes as themselves, and sometimes as inspirations for similar characters. To the regret of fans, however, their adventures have never made it to the silver screen, or even to television.

The adventures of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser have been covered before here at Tor.com, by Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode in their always-excellent “Advanced Readings in D&D” column.

About the Author

Fritz Leiber (1910-1992) ranks among the greatest American writers of horror, fantasy, and science fiction, whose long career that started in the 1930s and continued at a high level into the 1970s. He was the son of actors, and studied theology, philosophy and psychology, with those intellectual pursuits giving his work an added depth that many of his contemporaries lacked. He was encouraged to become a writer through his correspondence with H. P. Lovecraft, and some of his early stories were inspired by Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. Leiber’s writing career was also influenced by his long correspondence with his friend Harry Otto Fischer, to whom Lieber gives credit for creating the characters of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, although it was Leiber who wrote nearly all of their adventures (reportedly, Leiber’s tallness and the small stature of Fischer also inspired the look of the two characters).

Leiber was a prolific author who produced a diverse body of work. While he alternated throughout his career between tales of horror, science fiction, and fantasy, he always seemed most comfortable with fantasy. His work was infused with a keen sense of fun and wit. He was liberal in his politics, and his work was often satirical, sometimes featuring biting satire. His writing was also dark and often complex, and Leiber was open about his struggles with alcoholism, which informed some of his works. His writing included topics like time travel, alternate history, witchcraft, and cats, and he was more open in portraying sex than many of his contemporaries. One of his works that’s stuck in my memory over the years is the sardonic A Specter is Haunting Texas, which I read in Galaxy magazines borrowed from my dad in the late 1960s.

Leiber’s work garnered many awards, including six Hugos and three Nebulas. His fantasy awards included the Grand Master of Fantasy Award and the Life Achievement Lovecraft Award. He was the fifth writer selected as a SFWA Grand Master, and was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2001.

As with many authors who were writing in the early 20th Century, a number of works by Leiber can be found on Project Gutenberg, including a personal favorite of mine, “A Pail of Air,” a story I read in my youth that haunted me for years.

Of Swords and Sorcery

The subgenre that came to be known as Sword and Sorcery (a designation reportedly coined by Fritz Leiber himself) has its roots in the adventure tales that filled pulp magazines in the early decades of the twentieth century. Many of those periodicals included tales of sword-wielding warriors in the Middle Ages, or in the far-off lands of the Orient. Then, in magazines like Weird Tales, authors like Robert E. Howard began to infuse elements of magic, horror, and fantasy into these tales (you can read my previous column on Robert E. Howard’s character Conan here). Fritz Leiber’s tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser were another iteration of this new brand of adventure tales. Another close cousin of Sword and Sorcery tales were the Planetary Romances, where characters like Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter and Leigh Brackett’s Eric John Stark fought magicians on Mars or elsewhere with plenty of swordplay (you can see a review of Brackett’s work here).

These stories, however, were long confined to the relatively narrow audience of the pulp magazines. As I recounted here, however, the paperback publication of The Lord of the Rings in the 1960s marked a turning point, generating wide interest in quasi-medieval adventures. This created a demand that publishers rushed to satisfy, looking for similar stories. One source was the work of Robert E. Howard, which gained even greater popularity than he had enjoyed during his lifetime. And of course there were new authors, including Michael Moorcock with his dark tales of Elric of Melniboné. While Fritz Leiber had been an early writer of these tales, his career was still going strong during this period, and he was happy to continue writing the adventures of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

Fantasy adventures have become an established and highly popular part of the field these days, with the grittier of the tales still referred to as Sword and Sorcery stories, and those that follow in the footsteps of Tolkien being referred to alternatively as High, Heroic, or Epic Fantasy. An article on the theme of sword and sorcery can be found online at the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, for those interested in further reading.

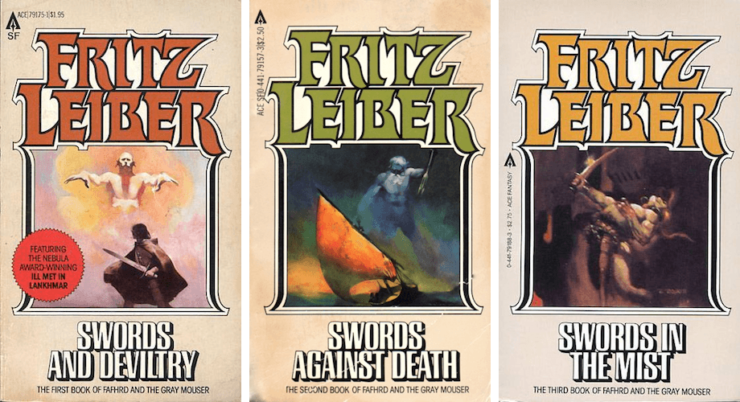

Swords and Deviltry

This book is not a novel, but instead consists of a pair of introductions and three closely linked tales, collected in 1970. It is first introduced by the author, who without any trace of modesty, false or otherwise, states:

This is Book One of the Saga of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, the two greatest swordsmen ever to be in this or any other universe of fact or fiction, more skillful masters of the blade even than Cyrano de Bergerac, Scar Gordon, Conan, John Carter, D’Artagnan, Brandoch Daha, and Anra Devadoris (Footnote: Brandoch Daha is a character from E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, while the last, Anra Devadoris, is another of Leiber’s own characters). Two comrades to the death and black comedians for all eternity, lusty, brawling, wine-bibbing, imaginative, romantic, earthy, thievish, sardonic, humorous, forever seeking adventure across the wide world, fated forever to encounter the most deadly of enemies, the most fell of foes, the most delectable of girls, and the most dire of sorcerers and supernatural bests and other personages.

…which is a much better capsule description of those characters than I could ever write.

The next introduction is a short vignette written in 1957 that introduces the reader to the mysterious world of Nehwon, a quasi-medieval land that sits apart from ours in both space and time, a land of decaying cities, mysterious monsters, magicians and sorcerers.

The first tale, “The Snow Women,” is a novella that first appeared in Fantastic magazine in 1970. In it, we meet Fafhrd, who is not yet the brawny hero of the later tales, but instead a slender and callow youth, who still lives with his mother at age 18 As his mother wishes, he wears the white clothing normally worn by women of their Snow Clan, is trained as a bard, and is expected to speak in a high tenor voice. His mother is the leader of the snow women of the title, and a powerful witch. Fafhrd’s father died after climbing a mountain against his wife’s wishes, and there are some who say her witchcraft led to his death. In fact, throughout the story, Leiber never makes it clear whether the weather, falling trees, and other occurrences are the result of magic, or simply coincidences, which heightens the narrative tension. And Fafhrd’s mother is not only overly controlling, but also insists that they pitch their tent on top of his father’s grave (Leiber is not above using his knowledge of psychology to bring an element of horror to a tale). Fafhrd, despite his appearance of obedience, chafes at the constraints placed on him. He has been on a raiding expedition to the south, and is fascinated by the lures of civilization. He also has gotten a girlfriend pregnant, although later finds that his mother is willing to accept this development as long as the young couple moves in with her.

Buy the Book

Warrior of the Altaii

The plot of the story kicks into action when an acting troupe visits the clan—something the men welcome, and the women only tolerate. Fafhrd is attracted to, and sleeps with, one of the women in the troupe, the worldly Vlana. While he is fascinated by her civilized charms, she is also amoral, and in her own way as demanding as his mother. Fafhrd has a choice, either to abide by his mother’s wishes and stay with his clan and girlfriend, or to succumb to the lures of Vlana and the civilizations of the south. And in order to pursue his dreams, he has to contend with rivals in his clan, his mother’s spells, his girlfriend’s wishes, and other men who are pursuing Vlana. Since he has to travel south to meet the Gray Mouser, we know where the story will be going, but getting there provides a fun and gripping tale.

“The Unholy Grail” is a novelette that also appeared in Fantastic magazine in 1962, which introduces us to the youngster who will become the Gray Mouser, but at this point in his life is simply known as the Mouse. He returns to the house of his sorcerer master, Glavas Rho, only to find that he has been murdered by the cruel and evil local Duke. The Mouse decides to pursue revenge, using all the skills the sorcerer had taught him…and some that he had warned him to avoid. His pursuit is complicated by the fact that Mouse is in love with the Duke’s sweet and sensitive daughter, Ivrian. This does not deter the Mouse, and even the fact that he uses Ivrian as a channel for revenge against her father does not extinguish her love for him. Thus, with his true love in tow, the Mouse heads off for the big city and a fateful meeting with Fafhrd.

The third tale, “Ill Met in Lankhmar,” is the jewel of this collection: not only one of the best of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser’s adventures, but a story I’ve come to appreciate as one of the best fantasy stories I’ve ever read. The novella first appeared in 1970 in Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine and won both the Nebula and Hugo awards. In the seamy city of Lankhmar, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser meet while attacking two members of the Thieves’ Guild who have just stolen a priceless cache of jewels. The two of them immediately hit it off, and decide not only to split the proceeds, but to celebrate with mass quantities of alcohol. Fafhrd takes the Mouser to meet his beloved Vlana, who has been pushing him to carry out a vendetta she has against the Thieves’ Guild; Fafhrd wants to pursue vengeance by stealing from them rather than killing them. The three then go to the Mouser’s apartment to meet Ivrian, who takes Vlana’s side, and encourages the Mouser to join the vendetta. Fueled by alcoholic courage, Fafhrd and Mouser decide to assault the Thieves’ Guild headquarters, promising to kill the King of Thieves. They return unsuccessful but unscathed, only to find that a Thieves’ Guild sorcerer has murdered their true loves. What was a drunken lark becomes deadly serious, and out of their shared loss, a lifelong partnership is born. The story is every bit as action-packed and darkly humorous as I remembered, and gallops along from start to finish. My only criticism upon revisiting it is that the story is built around “fridging” the female characters; their role in the narrative is primarily to die, thus causing the intense pain that fuels the actions of the male characters.

One shortcoming of this volume is that we don’t get a chance to meet the sorcerers who appear in so many of the duo’s adventures, Fafhrd’s patron warlock Ningauble of the Seven Eyes, and the Gray Mouser’s patron warlock Sheelba of the Eyeless Face. These two characters are a fascinating part of the saga, and I had been looking forward to encountering them again.

Final Thoughts

The adventures of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser remain as fun and exciting as I remembered, and reading these early exploits left me wanting more. When I was younger, I didn’t always appreciate their adventures as much as those of Conan or Kull, but as a more mature (well, actually, elderly) reader, I found subtleties and nuances in these stories that I didn’t fully understand in my youth.

And now, I’m eager to hear your thoughts: Have you read Swords and Deviltry, or the other adventures of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser? What are your other favorites from Leiber’s work? And what other sword and sorcery stories have you read and enjoyed?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.