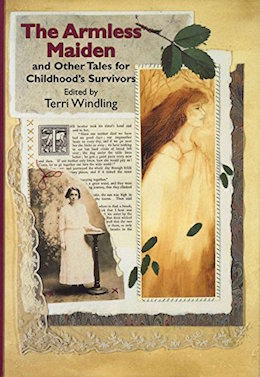

One of the most profound influences on my understanding of fairy tales was The Armless Maiden and Other Tales for Childhood’s Survivors (1995), edited by Terri Windling, an anthology I discovered quite by chance while browsing a bookstore one day. I picked it up partly because of the title, partly because it had a couple of stories from favorite authors, partly because it seemed to be about fairy tales, and mostly because it had a nice big sticker proclaiming that it was 25% off.

Never underestimate the value of nice big stickers proclaiming that things are 25% off, even if those stickers end up leaving sticky residue all over your book, which is not the point just now.

Rather, it’s how the book changed my understanding of fairy tales.

The Armless Maiden was hardly the first collection of fairy tales that I’d devoured, or even the first collection of fairy tales littered with essays about fairy tales, their origins, and their meanings. But it was the first collection I’d read that focused on a very real part of fairy tales: how many of them center on child abuse.

And not just the housekeeping demanded of poor Cinderella.

Neither I nor the collection mean to suggest that all fairy tales are about child abuse—many tales featuring talking animals, for instance, like “The Three Little Pigs” or “The Three Billy Goats Gruff,” do not deal with issues of child abuse, even when they do deal with violence. Other tales, such as “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” focus on figures who are not children, although they may be trapped, enchanted, and abused in other ways. And the French salon fairy tales, in particular, were more interested in issues of French aristocratic society than in child abuse: their intricate fairy tales, for the most part not intended for children, generally focused on violent relationships between adults.

But as the essays in the collection point out, a surprising, perhaps shocking, number of fairy tales do focus on child abuse: neglected children, abandoned children, children—especially daughters—handed over to monsters by parents, children killed by parents. Children with arms and legs cut off by parents.

This is the fairy tale subtopic that The Armless Maiden explores through essays, poems, fairy tale retellings, and original tales—some without any magic or fairies at all, as in Munro Sickafoose’s “Knives,” one of the most brutal stories in the collection. The contributors include renowned writers and poets Patricia McKillip, Charles de Lint, Anne Sexton, Peter Straub, Tanith Lee, Louise Gluck and Jane Yolen, with cartoonist Lynda Barry adding an essay.

With the exception of a few (much needed) lighter stories, like Jane Gardam’s “The Pangs of Love” (a sequel, of sorts, to Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,”) and Annita Harlan’s “Princess in Puce,” (a comparatively lighthearted Cinderella story), and a comforting story, “The Lion and the Lark,” from Patricia McKillip, the stories, poems and essays here are all fairly dark and grim, and, as with the original fairy tales they echo, not all have happy endings. Some are pure fairy tale, set in some timeless setting, as the story that starts the collection, Midori Snyder’s “The Armless Maiden” (which lent its title to the collection), and Jane Yolen’s “The Face in the Cloth.” Some—especially, but not limited to, the poems—are meditations on or explorations of existing fairy tales, such as Steven Gould’s “The Session,” a retelling of a conversation between a character in Snow White and a therapist, and Louise Gluck’s “Gretel and Darkness.” Others, such as Charles de Lint’s “In the House of My Enemy,” a tale of art and an orphan, featuring characters Jilly Coppercorn and Sophie Etoile from some of de Lint’s other books, are set in the present day. Most, with the exception of Peter Straub’s “The Juniper Tree,” are relatively short. I’m not sure they all work, but they all have a certain power.

Perhaps the most powerful contribution, however, is the personal essay/memoir from editor Terri Windling, explaining her own past with her mother and half-brother, and how that past became entangled with fairy tales. As Windling shows, both in this essay and elsewhere, fairy tales can serve as a reminder that yes, terrible things can happen to children. That not all adults are good, and sometimes, the real threat comes from within a child’s family.

Buy the Book

Miranda in Milan

But fairy tales also offer something else: hope that violence and terror can be survived. That children—and adults—can find a way out of their dark woods.

Possibly with the help of fairy tales.

Reading it, I was encouraged to start writing my own.

The Armless Maiden and Other Tales for Childhood’s Survivors is currently out of print, although I suppose it’s just possible that Tor Books might consider reprinting it if this post generates enough comments. (Or not.) But even if it doesn’t return to print, I’d argue it’s still worth seeking out in libraries or used bookstores. It is not an easy read, or something to be read quickly, and many readers will find the contributions from Tanith Lee, Peter Straub and Munro Sickafoose, in particular, disturbing. But it’s also a collection that few fairy tale lovers and scholars should miss.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.