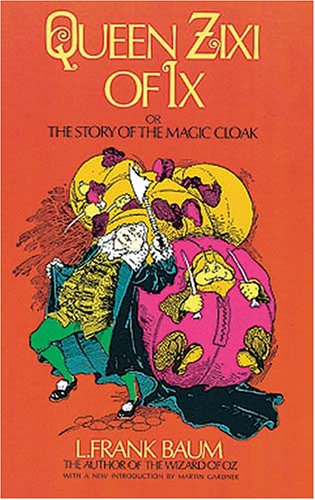

By 1904, L. Frank Baum had established himself as a popular, innovative children’s fantasy writer. Brimming with confidence, not yet tied down to the Oz series that would later become such a weight around his neck, and ignoring the pleading letters from children wanting more stories about Dorothy, he decided to try his hand at a more traditional fairy tale. Originally published as a serial story in the popular and influential children’s magazine St. Nicholas, the completed novel, Queen Zixi of Ix, would become one of Baum’s personal favorites. Many Oz fans list this among Baum’s very best, even if it is not an Oz book.

Like a proper fairy tale, Queen Zixi starts in the magical Forest of Burzee, with a group of fairies facing a serious problem: boredom. (All that eternal dancing and merriment does grate on the nerves after a time.) To combat boredom, they decide to create a magical cloak that will grant its wearer one—and only one—wish.

Yeah. That should go well. Have the fairies never read any fairy tales?

Meanwhile, over in Noland, a group of elderly government officials with very silly names are facing a different sort of crisis: their king has just died without naming or having an heir. In an alarming scene that explains much of the rest of the novel, it takes the government ministers several hours to think that maybe—just maybe—checking to see what the law says about situations like these might be helpful. Then again, the law is so silly that their failure to think of consulting their law books might be understandable: the forty-seventh person to enter the gates of the capital city, Nole, after the first sunrise after the death of the king shall become the new king, not generally the recommended method of choosing new leadership. Nonetheless, the ministers try this method, and as chance would have it, this forty-seventh person, a young boy named Bud, just happens to have a sister called Fluff who just happens to be wearing the wish granting fairy cloak.

Things like that just happen in fairy tales.

But in a nicely realistic touch for a fairy tale, Bud initially turns out to be a very bad king indeed, more interested in playing with his new toys than in ruling or dispensing justice. When he is, very reluctantly, brought to do his kingly duties, he turns out to have no idea what he’s doing. With the help of his sister, he does manage to make one judicious decision, and immediately flops on the very next court case.

Equally unsurprisingly, the wishes granted by the magic cloak are creating further havoc in a kingdom trying to adjust to the rule of a seven year old. Most of the cloak’s many wearers have no idea that it grants any wishes at all, and are thus rather careless with their words, with rather dangerous effects.

You might have noticed that I haven’t mentioned Queen Zixi yet—this because she does not make an appearance until about one third of the way through the book. Once she does, however, she immediately begins to dominate the tale: Zixi is hero and villain at once, a gifted leader with an often kindly heart who has led her kingdom into prosperity and peace, but is also tortured by her own desperate desires.

Zixi rules the neighboring kingdom of Ix, and has for hundreds of years, always looking like a young beautiful woman thanks to her powers of witchcraft. And yet. That witchcraft has limitations: when she looks into a mirror, she is forced to see the truth, that she is nothing but an ugly elderly hag. This is a truth she cannot tolerate. (It’s not clear why, under the circumstances, she keeps any mirrors around at all, but perhaps she wants to lull suspicions, or she just wants to make sure that her dresses don’t make her also look fat. She is that sort of person.)

When she hears about the cloak, she realizes that a single wish might be the answer to her problems. If, of course, she can obtain it, which is not quite as easy as it might sound. And if, of course, she doesn’t suddenly realize exactly what she is doing.

This type of characterization, not to mention character growth, is somewhat atypical for Baum,who usually kept his characters either basically good (most of the Oz cast) or basically evil (his villains), with only a few characters occupying a more muddled moral ground. Zixi is not inherently evil, and unlike most of Baum’s villains, she is capable of self-reflection, and most critically, capable of actual change. Nor is Zixi the only character to change and grow: Aunt Rivette, Bud and even some of the counselors do so.

Like many of Baum’s novels, Queen Zixi of Ix wanders quite a bit, and its third plot—an invasion of Noland by creatures called Roly-Rogues, odd creatures that roll themselves into balls, has a distinctly anticlimatic feeling. Too, its careful writing lacks some of the energy and sheer inventive power of his other works, along with a sense of what I can only call pure fun, a sense of adventure and exploration. The novel at times has a definite didactic air, particularly in a crucial scene where Zixi speaks to an alligator, an owl and a child about the sense of certain wishes.

Although Baum was not necessarily known for following editorial suggestions, it’s entirely possible that this tone was added at the insistence of St. Nicholas Magazine, known for publishing “wholesome” stories, and the same publication responsible for inflicting Little Lord Fauntleroy upon the world. Or perhaps Baum was merely absorbing and reflecting the morals emphasized in so many 19th century versions of traditional fairy tales. Whatever the reason, this didactic tone kept Baum from letting his humor and wordplay stretch to its heights. And let’s just say that battle scenes are really not Baum’s strong point.

But as pure fairy tale, Queen Zixi works very well. If not quite as funny as some of Baum’s other books, it still contains several amusing scenes, notably those involving Noland’s government ministers. Baum’s contempt for government and particularly bureaucracy shines through here, and in his sarcastic hands, the concept of government ministers unaware that their country even has a law code is perfectly believable. And above all, Queen Zixi shows that Baum could, when he chose, create fully three dimensional characters with the capacity for thought and change. It’s a fascinating look at what can be done within the structure of a traditional fairy tale—not usually associated with strong characterization or character growth.

Queen Zixi, King Bud and Princess Fluff were to make cameo appearances in the The Road to Oz in a nice early example of crossover fiction. Even in that brief appearance, Zixi makes a powerful impression (greatly helped by a spectacular illustration from John R. Neill) but this was not, sadly, enough to raise sales for the earlier book. Queen Zixi of Ix wandered in and out of print for years, and until the advent of the internet, was not the easiest book to track down. A pity: those who missed this in childhood or later missed a thoroughly satisfying book.

Mari Ness isn’t certain what she would do after an eternity of dancing in magical forests, but she is fairly sure that weaving a wishing cloak wouldn’t be high on her list of things to do. She lives in central Florida.