To the non-horse person, a horse is pretty much just a horse. There’s the really big one like the beer-wagon Clydesdale and the really little one like the Mini doing therapy at the hospital. Then there’s the one that races and the cowboy one. And the wild one. The rest are black, brown, white, or spotted, and sort of blur together.

Which is how I sometimes think movie people pick their horse actors. I know it has more to do with what the wranglers and trainers have available than with straight-out lack of knowledge, but sometimes I do wonder.

Film being a visual medium means looks count for a lot, and not just with the human stars. The animals have to look good, too, even if that means a glossy, well-fed, shiningly clean, perfectly groomed to show standard grey horse allegedly belonging to an impoverished family. Humane regulations require that the animals in a film be well fed and treated, but a plainer animal and a little cosmetic dirt would be more authentic in the context.

That’s fairly minor in film terms—the human actors tend to be spit-shined and too impeccably groomed, too. What catches horse people up short in films with horses in them are horses that aren’t actually suited to the jobs they’re shown as doing, and horse breeds that did not exist in period, and wee delights like stirrups in Roman epics (no stirrups till after Rome fell—like, age of Charlemagne in the West). And there’s also my personal peeve, the wrangler who taught Every Single Actor In Or Out Of Hollywood to leap on his horse and yell, “Hyaah!” to make the horse go.

I tried that once. The horse looked at me like, You done screeching, monkey? Can we go now?

That’s right up there with Every Single Coach And Stage Driver Everywhere slapping the reins to make the team go. No. No no no. Not done. This is probably where all those fantasy novels got “He shook the reins to make the horse he’s riding go,” too. Also very no.

One horse breed is just about Everywhere in fantasy and medieval films. That’s the big black one with the flowing hair. It’s a breed, and a somewhat rare one, and it’s called the Friesian.

Friesians are downright gorgeous, and they tend to have a lovely temperament. Proud but kind. Tolerant of human foibles. They’re flashy movers, too, with lots of knee action to get the hair flowing. As I said, lovely.

The first one I noticed in a film, as did every other horse person with access to modern technology, was Navarre’s mount in Ladyhawke. His name was Goliath, and he was a big boy; when we were done fangirling over him, we sighed over the beauty of the young Rutger Hauer.

Apparently the actor and the horse bonded. They certainly had chemistry on screen. And oh, the eye candy!

Thing is, if this is supposed to be a medieval setting, there wouldn’t have been any Friesians. Friesians were bred in much later times to pull funeral coaches in Flanders. Hence the glossy black coats, the high knee action and the flashing trot which can be hard to sit, and the overall build and mass, which are more suited to a coach or draft horse than a riding horse.

Somewhat more accurate would be the white horses with the flowing hair who also appear in the film. Those are Iberians, horses of Spain and Portugal, and they were known in the time of El Cid, having come down from the Roman era. Note the smaller height, the lighter build, and the lack of feathering on the legs. Those are horses bred to ride.

Now mind, the great horse or destrier of the medieval knight was pretty much a draft horse. The Shire horse of England according to legend was bred under King John for knightly use, and the Percheron of France descends from the destrier as well. They’re both still with us, and still excelling in any activity that requires pulling. Crossed on lighter breeds, they’re popular as field hunters, jumpers, and all-around riding horses.

The knights’ destriers were incredibly valuable animals, often worth more than the knight’s entire demesne, between their breeding and their training, and they were not casual riding horses. When they were not being ridden in the charges or in jousts, they were led; the knight would want to save his horse’s strength for the fight, and not wear him out riding him to it.

Because, you see, big, heavy horses are not big on stamina. It’s a terrible idea to take a Draft horse to an endurance race. They function best in short bursts that use their weight to advantage: charging an enemy line, pulling a log out of the woods.

Friesians have actually been studied, and their cardiovascular systems are not quite enough for the bulk of their bodies. As a trainer told me once, “Their hearts and lungs can’t keep up. They don’t have any stamina.”

Of course Ladyhawke is a fantasy. It’s not set in a real medieval world, so it can use whatever horses it wants. But by sticking with his beloved Goliath in his wanderings, Navarre has set himself some challenges. The horse can’t travel far per day especially in hot weather. He eats a lot. A Lot. Grooming is a constant process—all that hair tangles, and needs regular maintenance. And keeping his coat from fading in the sun takes work as well.

In my head canon, the two are so devoted they can’t be parted, and Navarre can’t afford a second horse in any case, even if he wanted to keep one for Isabeau in case they ever revert to permanent human form. So the destrier becomes the daily mount, and being who he is, which means he’s as sweet as the day is long and he loves his rider to death and beyond, he does the very best he can. And Navarre nurses him along and pampers him and watches over him.

Having Mouse along to help is a big relief. Poor man, he’s got as much as he can handle, what with the Lady Hawk and the evil bishop and the general mess his world is in. And then he has to spend every night running as a wolf. He never gets any sleep.

I’m good with Goliath in this film. It’s all gorgeous people and animals doing grand fantasy things. But it started a trend, not always to best effect. Jaime Lannister riding north on that nice Friesian is a pretty image with lots of symbolism, but that’s not a horse I’d pick to ride a thousand miles in the dead of winter. Cold tolerance he’s got, but a hard keeper without much stamina is a poor choice for the job. Jaime’s not going to be able to change him out at posting stations, either, if he’s riding incognito.

If I were his master of horse I’d find a sibling of that dear loyal white horse Jaime lost to dragon fire. He looks as if he has some desert blood in there, ergo stamina, and he’s probably a fairly easy keeper. He can go the distance.

Shifting to the other end of the gorgeous black horse spectrum, there’s the Black in The Black Stallion, played in the film by Cass Ole and an assortment of body doubles. Here’s stamina to burn: the Black is an Arabian, also known as the endurance mount. If you want a horse who can go 100 miles in under 16 hours and finish with energy to spare, that’s an Arabian.

They go easy on the feed, too. They’re not heavy enough to carry a knight in full armor, but they’ll get him to the battle (with his armor packed on a sumpter mule) and they’ll take him on the long chase after to round up stragglers. They can run rings around the heavy destriers—as the armies of Islam did in battle after battle to the Crusaders—and thrive on an amount of feed that would barely keep the destrier alive.

The Black is pure fantasy, but parts of his story are surprisingly realistic; kids have been sneaking rides on horses sans tack for millennia. What’s not real is the idea of an Arabian entering Thoroughbred races. That doesn’t happen. There are Arabian racing circuits, and there may be exhibition races, but Thoroughbreds race with each other—purebred horses from specific bloodlines, registered with the Jockey Club. They are descended from Arabians, but they’ve long been their own breed. No outsiders can apply.

There’s also the fact that Arabians and Thoroughbreds are two different kinds of runners. Thoroughbreds are milers—middle-distance runners. The Quarter Horse, who is a sprinter, will leave them in his dust at the quarter-mile, but the Thoroughbred rules the mile.

The Arabian at that distance is still getting started. He won’t match the speed of the Thorougbred in the shorter distance, but as the race gets longer, the miler poops out and the Arabian is still going. He’s the marathon runner of the horse world. Horse people know that training methods designed to tire out a Quarter Horse will give you a very fit Arabian. He’s not going to stop; he’ll go and go.

And that brings me to one of the biggest examples of facepalm casting I know of. Hidalgo is allegedly based on a true story, but let’s just say the guy who told it was working in the grand tradition of the American tall tale. It’s about a horse from the Wild West who was entered in an allegedly famous race across Arabia. (The race never existed. The horse maybe did, but his owner/promoter was more than a little bit free with the truth.)

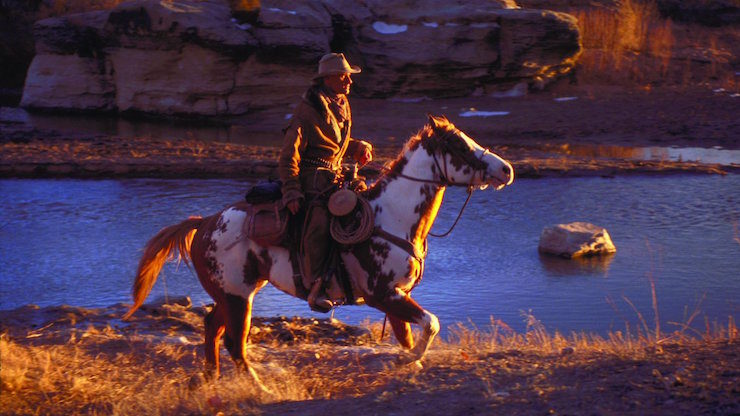

The horse in the story was a Mustang, and the original star of the film, as in the legend, was a Spanish Mustang. But he was unable to participate, and was replaced by a small herd of American Paint Horses.

Mustangs, descended from Spanish horses brought to the Americas by the Conquistadores, are feral horses. They’re small, tough, smart, and have tons of stamina. Paints are a modern breed. They’re supposed to be lavishly spotted, as the horse in the film is, and their ancestry is primarily Quarter Horse and Thoroughbred. In the case of the horse in the film, by body type, mostly Quarter Horse, and modern Quarter Horse at that.

A sprinter. In a film about a marathon to end all marathons. In which the star runs against Arabians.

Nope. Nope nope.

The horse who gets the most air time is adorable, in fact they all are. Viggo Mortensen was so taken with one of them that he bought the horse—Viggo is a real horse person; he tends to fall in love with his movie partners. He bought Brego from LOTR, too.

But these are not endurance horses. Quite apart from the fact that there never was any such race, that lovely chunky spotty boy would not have been a contender. That’s not what he’s made for. He’s designed to run short sprints, and to stand up in a show ring and be judged for his very particular conformation and his spectacular coloring. He’s an artifact of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, and bears little resemblance to the horses of the period in which the film is set.

An actual Mustang might have managed. Mustangs have the stamina, the smarts, and the feet (feet are a huge issue with the Quarter-Horse-based breeds, to the point that many have serious problems functioning). They might not win on speed, but they’ll hold the line on sheer cussedness and refusal to quit.

Since the film aired, a collection of adventurous horse people have put together their own very long endurance race—but in Mongolia. The Mongol Derby needs its own film, it really does. It sends a couple of dozen very, very fit riders to Mongolia, mounts them on Mongol horses from herds kept for the purpose, and lets them rip on routes taken by the post-riders of Genghis Khan. The horses, like Mustangs, are small, sturdy, tough, and massively opinionated. Riders change horses every day, for the health and safety of the horses—the riders have medical staff following them, but they have to make it through the whole race. The horses get to rest after their stages.

Now that’s a race, and it really happens every year. The riders are indomitable and the horses test them in every possible way. Real riders, real horses, but doing something straight out of a fantasy novel.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.

Are there any horse jobs for which we’ve lost the breed for? Or at least the modern descendants are so different that horse people would have fits no matter which breed was picked for the movie?

The Mongol Derby sounds interesting, especially the courier style set-up. I have a fondness for couriers in fantasy stories. There’s so much world-building packed into a very unobtrusive job.

So, since I know very little about horses, if I were trying to write a story about a modern someone needing to ride a horse all around as varied a country as the Midwestern US (hills, plains, prairies. valleys but no real mountains) with a moderate load (one person’s survival level gear) similar to some b movie cowboy/gunslinger riding from place to place – what would be a good horse? I always thought the Quarter would be reasonable but you mention feet issues I never knew about. A Morgan? Standard breed? POA? Arabian? And of these, which would be the easiest to find in a modern situation?

Combine that with a character who is well meaning and wants to care appropriately for the animal but may not have the best knowledge of how (hrm. Wonder if there’s like an old horse cavalry manual online somewhere to teach those basics…)

@1 Not sure any ancient job is still not done somewhere. My brain is a blank. I would say that the modern Quarter Horse and its related breeds bears zero resemblance to the breed of even forty years ago, it’s been bred for such specific traits for the show ring, but ranch horses and crosses are still out there doing the job. Same for the Arabian–show breed totally different from performance version. But again…

@2 Does it need to be a breed? A good old grade (mixed breed) horse is probably the answer, though if it has to be something specific, could be a ranch Quarter Horse, an old-fashioned Morgan, a performance-type Arabian, a retired racing Thoroughbred, a Standardbred (harness racer–they make great riding horses), etc., etc. Whatever is handy where the character lives. Here in Arizona it would be a Quarter Horse or Paint of some description, probably. Ranch-bred so it hasn’t had the feet bred off it. Or an Appaloosa. As long as the show-ring breeders haven’t got at it, it’s probably as functional as it needs to be.

Ah, like I say, I know very little. A non-show mixed breed is probably the best bet then. I’m reminded of reading that the horse cav wasn’t worried too much about breeds, just that the horse was strong enough to train. Same with the trooper, I’d bet… ;)

@3 That’s good. I was partially thinking of dog breeds where even before they were bred to current show standards, dog breeds not actively sustained disappeared with their jobs. Granted, the breed I’m thinking of was for rotating rotisserie spits which was horrible, it’s still gone.

@5 Horse breeds do come and go, but they’re more of a regional than a functional thing. If people stop cultivating them, they die out. Or they’re folded into another later breed, the way the Neapolitan only survives in one of the Lipizzaner bloodlines.

The Appaloosa was pretty much killed off by the US after the genocide of the Nez Perce, but was brought back through crosses with other breeds on what was left of the original stock. The Nez Perce are still doing this, even using a rare European breed, the Akhal-Teke, to recreate the old type, while the show type is basically a Quarter Horse with spots (if it has any color at all).

It is a lot like dogs. Same missteps. Same biases.

It’s not scifi or fantasy, but if you like anime and horses, you might like Silver Spoon. It’s got horse care, big draft horses doing pulling races, and lots of love.

@5

You sure turnspit dogs are gone? I knew any number of corgi owners who trained them to use treadmills to burn off energy that otherwise would have been turned to destruction. :D

@8 But the specific breed is gone, isn’t it? I’ve seen pictures of it. It’s a little terrier-like critter. Kind of cute. No resemblance to a Corgi. (I had Cardigans, will again; love those guys.)

Horse breeds never got that job-specific that I know of. It’s more area-specific, and culture-specific.

@8 Corgis were turnspit dogs? I was sure they disappeared.

@1 The original Arabians, prior to Europeans like Lady Anne Blunt beginning to buy and crossbreed them, were pretty different to today’s breed – they averaged around cob height (14 hands), and had less dishy faces than we’d recognize today. Some of the sketches I’ve seen of them from the time actually looked more like an Arab/Welsh Mtn Pony cross we used to own, where the face was still fine, but missing the bulbous forehead. Not sure if the ears have always been small. “Pilgrimage to the Nejd” and some of Blunt’s other works are available for free online, and she does talk a lot about the breed. One observation in her travels is that the Arabians they were buying or looking at often looked pretty unimpressive until they moved — and then they were splendid.

@2 try this manual for noncommissioned cavalry officers and privates – Archive.org can be very handy for out of copyright obscurities!: https://archive.org/details/manualfornoncomm00unit

@2 I just stumbled across this book that sounds like *precisely* what you’re looking for: “Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right.” By Judith Tarr. ;)

@10 I think #8 was joking, Corgis are actually shepherds–specifically bred to herd cattle, in fact. Which, you’d think it odd to have such a small dog herding such large animals, but their shortness is a feature–it makes it easier for them to nip at the cows’ heels to keep them moving, and they’re quick enough to avoid being stepped on.

Love this article! Please do a part 2! Tell us about palfrey and coursers, and Icelandic ponies. Also those glossy horses, akhal-teke. Who invented stirrups? How did they make the nazgul horses look so awful in LOTR? Many horse questions await!!

@13 That’s good for Corgi ancestors, since the turnspit job was awful. Though I suppose working Corgis still got stepped on occasionally.

The last point, about the Mongolian Derby makes me wonder something. The horses are Mongolian, while the riders are probably wealthy Western tourists, right? So… that means that all horses understand all riders the world over? Is there just one uh… riding language? One human-horse language?

Your talk about mustangs took me right to Banjo Patterson’s Man Horse from Snowy River:

“And one was there, a stripling, on a small and weedy beast,

He was something like a racehorse undersized,

With a touch of Timor pony – three parts Thoroughbred at least –

And such as are by mountain horsemen prized.

He was hard and tough and wiry, just the sort that won’t say die –

There was courage in his quick impatient tread;

And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye

And the proud and lofty carriage of his head.

wlewisiii, as a writer you have it easier than films, television and animation. The job is to not annoy horse-knowledgable readers, and if you describe what the horse is doing, they’ll mentally supply the breed in their head, unless you’re rash enough to name the breed. In the visual narrative arts, they have to show a horse, as well as showing what the horse is doing, and that’s where the trouble starts, with the potential for teeth-grinding mismatch.

So how do you make a horse go? Enquiring minds of non-horse-people want to know.

@16 The website implied that the steppe horses will object strongly to being treated like first world race horses. They know what they’re doing and would prefer if the idiot monkey on their back didn’t micro-manage them.

The Mongol Derby has its own film! Keep a lookout for “All the Wild Horses”. It’s currently at Aspen Filmfest. I can’t find any information about its release to wider audiences, but I’d assume it will at one point or another. They have a website and a YouTube trailer under the same name if you’d like to check it out.

@7- I checked out Silver Spoon. Usually anime animals hurt my eyes. The cows and pigs were too cute. The horses though…. Man, could people take one riding lesson before drawing or animating people riding horses? It would do wonders! XD

@13 – I’d always heard corgis were bred with short legs to avoid cow kicks, which would pass right over their heads in most cases :)

@16&19- Different regions have different ways of riding horses, but once you know the “horse language”, you can pretty much figure it out. Horses work off of pressure and release, so you squeeze the sides of the horse with your calves and the horse wants to escape the pressure, so it walks off. As soon as the horse does what you want, you release the pressure as the reward. You want this as opposed to treat-training because you want a 1000+lb animal to just listen to you if you’re riding it and not get stubborn because you forgot the carrots ;)

@17- The horse from the Man from Snowy River was probably a Brumby, since it took place in Australia. Similar to the mustang, Brumbies are just a mix of a bunch of different horse breeds that became feral.

This article let my horse nerd flag fly :D I love Friesians, but man, they are *every-where*. Glad that it was mentioned here! They’re gorgeous animals, but not well suited for every fantasy adventure ever.

Another fun fact, draft horses weren’t used by knights because they’re too big and low in stamina. Not to mention they’re super sweethearts, which makes sense as you want a 2000 lb animal to be as nice and docile while pulling your cart/ farm equipment as possible. They trained medieval war horses to kick out and trample people… I can’t imagine a kindly draft really having that much malice.

The Black Stallion did discuss the issues with the Black racing on American tracks and said he couldn’t for the reasons mentioned. The only way they’d be able to race him, Henry and the racing columnist said, was to goad some owners into a ‘private’ match race where rules didn’t apply and that’s what they did. So they stuck to the rules, at least in the first book.

Sorry about the silence. The site wouldn’t let me post replies. Let’s try again, a little outdated but…

@12 :) Thanks. I am so bad at tooting my own hunting horn.

@13 The story I heard is that Corgis (there are two separate breeds; the term is Welsh for “dwarf dog”) are built low so that when the cattle kick, the kick flies over the dogs’ heads. Eyeing the Shepherd mix on the sofa here, who broke a leg thanks to a horse kick, and where the break is located, hmm, yeah. One of my Cardigans would have been below the line of fire.

@14 A lot of your questions are answered in Writing Horses, but I’ll make a note to answer them in the next column. @19, I’ll answer yours, too. (Short form: touch with lower legs.)

Aaannnd…here’s the rest of it:

@16 Riding is riding no matter what verbal language the rider speaks. Horses have high verbal comprehension but words aren’t how we ride–they can be tools but the main instruments are our bodies on the horses’ backs. The equipment the horse wears is often culture-specific, and the ways the equipment is applied will have various conventions and traditions, like neck-reining in US Western riding and direct reining (pull rein in the direction you want to turn) in other styles.

But there are certain constants. You’re on the horse’s back. Your weight and movements affect him. If you lean right, he’ll tip right. If you squeeze him with your legs, he’ll move away from the pressure. If you kick him hard enough, he’ll move faster. Hit him with a stick, he’ll try to escape it.

It doesn’t have to be all pressure and punishment. In fact it shouldn’t be. Good horse training in any culture is subtle and quiet, and the horse learns the rider’s body signals on a deep level. Breathe out, the horse moves forward. Still the movement of the seat, horse stops. Apply a whisper of pressure with a seatbone, horse’s body and neck bend in response. Touch her side, she steps over.

That’s all body language, which is what horse language primarily is. I can get on a horse in Austria or South Africa or Japan and have a pretty fair chance of being able to make myself understood, as long as she hasn’t been totally shut down by bad handling. I might want to know what specific signals the horse has learned (like does he neckrein or direct rein or is there another form of asking for the same responses), but once I have a handle on those, the rest should fit together more or less coherently.

…as others have noted, but there you are.

For a well-researched story in this category, I nominate Black Horses for the King by Anne McCaffrey – positing an expedition by Lord Artos (aka Arthur, not king yet) to acquire African horses that are big and sturdy to be able to carry armored knights in battle. The story is told by a young man who goes along and ends up working with an older man to invent horseshoes to protect the horses’ feet, which are adapted to a dry climate, not the dampness of Britain. A very fun read, and while some of Anne’s books have their own issues, there’s no denying that she knew her horses.

@22 I’ve met some scary Drafts. Bad-attitude Belgians. A proud-cut Percheron who was severely dangerous–and he was well over 18 hands.

They’ve been bred differently since the armored knight went out of style. The gentle giants we know now are both bigger and less aggressive than the medieval destriers. We geld them, too, and a knight would seriously object to that. Knights rode stallions. Machismo, you know. An ungelded, 2000lb, 18hh horse is a Lot of testosterone bomb.

I do not believe that most knights rode stallions. I think that the highest percentage of fighters actually rode mares (I know this is true of the Bedouins and their Arabians). The mares did not have the attitude issues that stallions do or the unfocused aggression.

Fun history, a Bedouin’s prized mare was treated like a treasured member of the family. She slept in the tent during bad weather (or just to keep her safe from thieves) and was part of the family defense plan. And any mare that could not be trained to an adequate level, which was pretty extreme, was not allowed to be bred. Most male horses similarly were considered culls and their female branch was usually the deciding factor regarding whether they would be breeding stock or not.

Here’s a link to more info if you’re curious about Arabians: https://www.arabianhorses.org/discover/arabian-horses/ (and yes, I grew up on an Arabian breeding farm and helped train horses since I was a child)

@23 Western knights did indeed ride stallions. It was a thing. Still is in places like Spain. Stallions in groups away from mares have severely reduced hormones, a la bachelor bands, and are lovely mounts with lots of fire and strength. Extra muscle mass, you know.

Stallion owners in the UK and the US have many tales of the myths around the gender, in our gelding-centric equestrian society. But the prejudice against mares is just about as strong. As a mare person from childhood, I take umbrage. I love the stallions, too. Regularly ride and train both.

I’m quite familiar with Arabians. Knew some of the early Al Marah herd in the US and saw the late incarnations while Mrs. T was alive since I live fairly close, have a half-Arab here now whose sire was line-bred *Raffles. Used to ride a *Morafic grandson who was hot-hot-hot but oh what fun and so bonded. I swear my Lipizzaner stallion (whose bloodlines have quite a few Arabs in them) is his reincarnation. They’re basically the same horse. :) (For those playing along at home, the * signifies an import to the US.)

Great article! I love horses, and love seeing what kinds are used in TV and movies. I know that there are often instances in which different horses are used for the same horse on screen, for various reasons, but I hate when it’s really noticeable. At the end of LOTR: The Two Towers, the horse playing Shadowfax has such a dark gray muzzle– I’m pretty sure it’s a different horse from the one we mainly see.

In the TV show Merlin, I think the location used for Camelot was completely different from where they filmed the scenes of the them riding through the forest, so there were numerous times when the gang would ride out from the palace on fancy horses– like really distinct ones– for example an Andalusian (I think), white or light grey with a long wavy mane and tail, and then in the next scene in the forest, the horse would also be white or light grey, but clearly a different horse. I wonder why they wouldn’t try to keep some semblance of continuity with less showy horses?

But it’s fascinating to see a quick rundown of the uses of the different breeds. I do love that Friesian from Ladyhawke!

@22 and especially @25 – That‘s fascinating. Thanks for the replies.