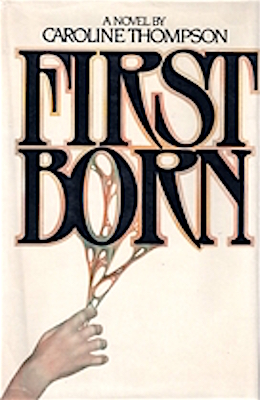

Long before Caroline Thompson wrote the screenplays for Edward Scissorhands or The Nightmare Before Christmas, she wrote this dark, deeply weird novel called First Born. She sold director Penelope Spheeris the rights to the film adaptation for $1, and adapted her first novel into her first screenplay. The film was never made, but it launched Thompson on a new career in Hollywood, and she soon met Tim Burton at a studio party. The two bonded over feeling like nerdy outcasts in a room full of Hollywood insiders.

As a lifelong Tim Burton fan, I’ve been meaning to read this book ever since I first found out Thompson had written it. It took me a while to track a copy down, but even after I had it I was nervous about cracking it open. Would it be worth it? Does the book offer a glimpse at the writer who would later pen some of my favorite movies? I only knew that the plot concerned abortion, and that it was literary horror.

The book is both more and less than what that description promises.

First Born is the journal of Claire Nash, which has been edited, footnoted, and published by a family friend, after a tragedy that is alluded to in an introduction. This works for and against the book—journal entries are quick and easily readable, but they also mean that any longer philosophical musings or scene-setting begins to feel forced.

At the opening of the novel, Claire and Edward are a lovely young couple living in a suburb of DC. Edward is in law school, and hopes to get into politics; Claire has a nondescript office job that she hopes to quit for motherhood once they’re established.

The reader goes into the book with a Damoclean sword hanging over the narrative: what’s going to go wrong? Where is the couple’s fatal mistake? One of the excellent things about the book is that there is no mistake. Tiny decisions lead to more tiny decisions, and gradually, imperceptibly, everything falls apart while Claire is trying to do her best for her family. The book functions far better as a chronicle of domestic unrest than as a horror novel—it’s sort of like a more gruesome Revolutionary Road.

Claire discovers she’s pregnant while Edward is still in school. She is by turns thrilled and terrified—she wants nothing more than to be a mother and homemaker, but she knows they can’t afford a family yet. When she tells Edward he is crushed, but starts making plans to put law school on hold and planning to work in a factory for a year or two and before going back. Claire knows after her own experience of dropping out of Bryn Mawr to work that it’s almost impossible to go back to school after you’ve left, so she gets a secret abortion, tells everyone she miscarried, and they carry on with their lives.

The journal picks back up a few years later. Claire and Edward have had another child, Neddy, who is nearly four years old. Edward is the rising star of his law firm. Claire remembers the abortion with an entry each year, but doesn’t write much in her journal until Neddy’s birth in 1976, then stops again. Each year she notes the anniversary of her abortion in much the same way that she remembers the date of her mother’s death. In 1979, she notes a single nightmare in which the aborted fetus survived. In 1980 however, things change, and she begins writing long, involved entries. The family moves closer to D.C., Edward’s career picks up, and Claire becomes part of a group of young mothers who pool their resources to host playgroups each week. She also begins to ingratiate herself with Edward’s boss and his wife, who become their neighbors.

After they move, the book briefly flirts with being a haunted house story. Claire begins seeing shadows, hearing noises, and seeing a strange, half-formed creature in the corners. Neddy becomes accident prone, and claims after one fall that he was “running away from It.” Claire finds feces in the house, but Neddy denies responsibility. Finally she comes face-to-face with a creature that looks like a cross between a hairless monkey and a human infant. It has a crooked back, an arm that hangs dead from the socket, and a huge head. Claire tries to tell people, no one believes her. Claire sees reports of a strange creature in the neighborhood; but Edward’s increasingly distant behavior distracts her. Claire finds the creature and begins to care for it; Neddy is difficult and Edward is bordering on emotionally abusive.

Thompson modulates the book’s middle stretch quite well: is the creature a figment of Claire’s imagination? A ghost? Her abortion come back to haunt her in either a real or metaphorical way? An escaped lab experiment? But in the end I think she comes down too hard on one explanation for the book to fully work, and in turn that explanation sucks so much air out of the book that when tragedy finally does fall, it feels more like the neat wrap up at the end of a locked-room mystery than an organic ending.

The abortion itself goes awry in a way that is both horrific and bordering on slapstick comedy, but Thompson short circuits the momentum by cutting to another diary entry. This is one of those moments that stretches the conceit: Claire was traumatized by what was happening, but recorded it meticulously in her journal? But also never dwells on it or writes about it again? (You can already see Thompson’s eye for cinematic detail though, and I’m guessing this is the scene that made Penelope Spheeris want to adapt the book.) The book is more successful when it stays within that strain of horror like The Brood, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Unborn that revolve around issues of fertility, motherhood, and feminism in the decade after Roe v Wade. Thompson constantly vacillates on the issue of abortion, which gives an interesting window into American culture in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. While Claire never wrings her hands over the abortion, the procedure itself is traumatic to her. She believes she did the right thing, but it still comes back to haunt her in a visceral way… but only because of a series of extreme circumstances. The people protesting the clinic are painted as unfeeling and monstrous, but the creature (which, again, might be a human child) is shown as deserving of love.

It’s also interesting to see characters who would probably be far more conservative today fitting into what used to be mainstream suburban culture. Edward and Claire are Republicans, but Claire’s gynecologist—a male family friend who’s been her doctor for years—recommends an abortion without a qualm, saying it’s her right to have one. Later on, Claire switches to a female OB/GYN, and no one questions the idea of female doctors. Both sides of the family want Claire to go back to Bryn Mawr and finish her degree. Religion never comes up at all. There is no moralistic finger pointing in the book. Things just happen, and are reported either in the journal or in editorial notes without judgment.

Thompson is obviously riffing on Frankenstein—another story told through letters, journals, and editorial notes, and essentially telling the tale of a person haunted by an unwanted pregnancy gone monstrous. That classic is, if anything, too emotional, full of thunderstorms and lightning bolts, long tortured monologues, impassioned pronouncements. Here the story is flat, unadorned. Does suburban life flatten Claire? Does it drive her mad? She gradually discovers that her marriage to Edward is not the happy dream she thought it would be, but she reports his occasional feints toward physical abuse in the same way she talks about taking Neddy for ice cream. She accepts the creature, and begins caring for him, in those same matter-of-fact phrases. She describes feeding him and bathing him. She records Neddy’s increasing emotional problems, and moments that are almost certainly the creature attacking Neddy, but she remains removed from what’s happening to her and her child. Unfortunately for the book, the journal structure removes the reader still further, since everything Claire writes about is already in the past.

I’m glad I finally read the book, and it’s certainly an interesting look at a young writer’s career, but I found myself wishing that Thompson had committed more to either a domestic drama, or to the supernatural, or to body horror. By trying to hedge between genres, all the while sticking to an increasingly unwieldy journal format, Thompson undercuts her story. You can see the sensibilities that would make Thompson’s scripts unique in First Born: her command of horror and suspense, the tiny details that make the creature so uncanny and shiver-inducing, and even the subtle way she allows Edward’s abusive tendencies to creep into the marriage. I think that if she’d decided to tell a more straightforwardly supernatural story this book could have become a classic—as it is, it’s a fascinating glimpse at a young writer testing her limits and learning her strengths.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another will rise in its place. Come give her reading suggestions on Twitter!