In Jack Vance’s The Languages of Pao, an off-worlder named Palafox has a plan to save Pao. The Paonese, it seems, keep getting bullied by the Brumbo Clan from the planet Batmarsh, on account of their cultural passivity. According to Palafox, though, the root cause of the problem is the language that all Paonese share. In order to rectify the situation, Palafox hatches a preposterously circuitous plan, whereby he will create three new languages for the Paonese, each designed to elicit a certain characteristic response from its speakers. One of these languages will be a “warlike” language that will turn all its speakers into soldiers; another will enhance the intellectual capabilities of its speakers; the third will produce a master class of merchants. Once different segments of Pao’s population have adopted these languages as their own, the resultant cultural diversity will allow the Paonese to defend themselves against all comers.

The premise of this book is pure fantasy and has absolutely no grounding in linguistic science. Often when an author decides to incorporate language into their work, the results are similar, whether the story is entertaining or not. Certain authors, though, have managed to weave language into their work in a realistic and/or satisfying way. Below are five books or series that I think have done a particularly good job with their invented languages.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Let’s get the easy one out of the way first. Tolkien was, before anything else, a language creator, and we haven’t yet seen another work where the skill and depth of the invented languages employed therein equaled the quality of the work itself. The Elvish languages of Arda predated the works set in Middle-earth by decades, and though we don’t see a lot of examples in the books, every single detail ties in to Tolkien’s greater linguistic legendarium as a whole. There have been better books since Tolkien’s—and better constructed languages—but we have yet to see a combination that rivals Tolkien’s works, and I doubt we will for some time.

Let’s get the easy one out of the way first. Tolkien was, before anything else, a language creator, and we haven’t yet seen another work where the skill and depth of the invented languages employed therein equaled the quality of the work itself. The Elvish languages of Arda predated the works set in Middle-earth by decades, and though we don’t see a lot of examples in the books, every single detail ties in to Tolkien’s greater linguistic legendarium as a whole. There have been better books since Tolkien’s—and better constructed languages—but we have yet to see a combination that rivals Tolkien’s works, and I doubt we will for some time.

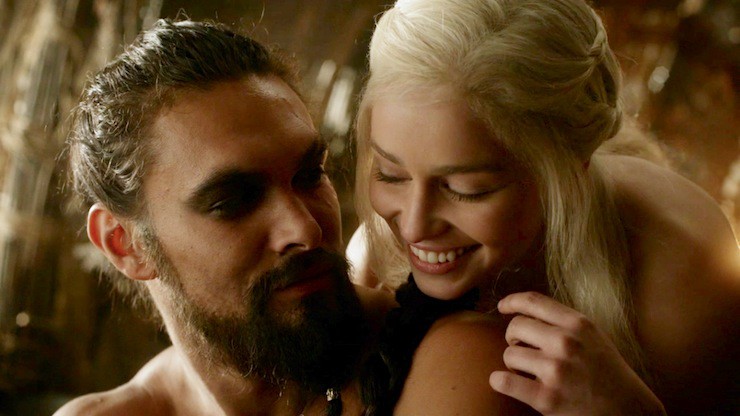

George R. R. Martin, A Song of Ice and Fire

Moving from Tolkien to George R. R. Martin, who created no languages for his A Song of Ice and Fire series, might seem like a step back, but there is a key trait that ties Tolkien’s and Martin’s works together. Though you’ll often hear it said, Tolkien’s elves do not, in fact, speak “Elvish”—no more than those currently living in Italy, Spain and France speak “Latin.” Instead, some of the elves speak Sindarin, which itself has four dialects, while others speak Quenya, which has two dialects, all of which are descended from a common ancestor, Primitive Quendian. And then, of course, there are languages for beings other than the elves, as well.

Moving from Tolkien to George R. R. Martin, who created no languages for his A Song of Ice and Fire series, might seem like a step back, but there is a key trait that ties Tolkien’s and Martin’s works together. Though you’ll often hear it said, Tolkien’s elves do not, in fact, speak “Elvish”—no more than those currently living in Italy, Spain and France speak “Latin.” Instead, some of the elves speak Sindarin, which itself has four dialects, while others speak Quenya, which has two dialects, all of which are descended from a common ancestor, Primitive Quendian. And then, of course, there are languages for beings other than the elves, as well.

This is the linguistic diversity we see in the real world that we rarely see in fantasy—and we see it too in George R. R. Martin’s work, where High Valyrian begat the Bastard Valyrian tongues, and where a realistic contact situation in Slaver’s Bay produces a modern mixed language from varying sources. Even though the languages weren’t worked out in detail, their genetic histories were, and these were done masterfully. For authors who don’t want to create a language on their own, or who don’t wish to hire a seasoned conlanger to create one for them, I recommend Martin’s work as a model of the right way to incorporate linguistic elements into high fantasy.

Suzette Haden Elgin, Native Tongue

In Native Tongue, Suzette Haden Elgin imagined a group of women trapped in a patriarchal society creating a language that would liberate them mentally and physically from male oppression. The idea that language by itself can effect change is, as mentioned previously, science fantasy, but unlike Jack Vance, Suzette Haden Elgin actually created the language she describes in her books. It’s called Láadan, and though it didn’t really catch on with women in the real world the way she hoped it would, the effort was an extraordinary one and stands as a rare achievement for an author tackling a linguistic subject in their work.

In Native Tongue, Suzette Haden Elgin imagined a group of women trapped in a patriarchal society creating a language that would liberate them mentally and physically from male oppression. The idea that language by itself can effect change is, as mentioned previously, science fantasy, but unlike Jack Vance, Suzette Haden Elgin actually created the language she describes in her books. It’s called Láadan, and though it didn’t really catch on with women in the real world the way she hoped it would, the effort was an extraordinary one and stands as a rare achievement for an author tackling a linguistic subject in their work.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire

Though Nabokov didn’t create a full language for Pale Fire, he created an interesting sketch of what we today would call an a posteriori language—a language based on real world sources. In Pale Fire, Nabokov follows the exiled former ruler of an imaginary country called Zembla, but even within the fictional context of the story, it’s not quite certain how “real” Zembla is supposed to be. One gets the same slightly unsettling sense from the Zemblan language, which at turns looks plausibly Indo-European, or completely ridiculous. Though used sparingly, the conlang material enhances the overall effect of the work, adding another level of mystery to the already curious text.

Though Nabokov didn’t create a full language for Pale Fire, he created an interesting sketch of what we today would call an a posteriori language—a language based on real world sources. In Pale Fire, Nabokov follows the exiled former ruler of an imaginary country called Zembla, but even within the fictional context of the story, it’s not quite certain how “real” Zembla is supposed to be. One gets the same slightly unsettling sense from the Zemblan language, which at turns looks plausibly Indo-European, or completely ridiculous. Though used sparingly, the conlang material enhances the overall effect of the work, adding another level of mystery to the already curious text.

Kurt Vonnegut, Cat’s Cradle

In Cat’s Cradle, Vonnegut introduces the reader to the island nation of San Lorenzo, whose culture, government, and religion were radically altered by the actions of two castaways who washed ashore one day. Central to the religion, called Bokononism, are a series of English-like words that were introduced to the island by English speakers, and then altered in quasi-realistic ways. For example, karass, likely from English “class,” is a group of people that are cosmically connected in an indiscernible way. From that word, though, comes the word duprass: A karass consisting of exactly two people. This is precisely the type of fascinating misanalysis that occurs all the time in real word borrowings, such as the English word “tamale,” formed by taking the “s” off “tamales,” even though the word for one tamale in Spanish is tamal.

In Cat’s Cradle, Vonnegut introduces the reader to the island nation of San Lorenzo, whose culture, government, and religion were radically altered by the actions of two castaways who washed ashore one day. Central to the religion, called Bokononism, are a series of English-like words that were introduced to the island by English speakers, and then altered in quasi-realistic ways. For example, karass, likely from English “class,” is a group of people that are cosmically connected in an indiscernible way. From that word, though, comes the word duprass: A karass consisting of exactly two people. This is precisely the type of fascinating misanalysis that occurs all the time in real word borrowings, such as the English word “tamale,” formed by taking the “s” off “tamales,” even though the word for one tamale in Spanish is tamal.

David Peterson holds an M.A. in linguistics from UC San Diego. He’s been creating languages since 2000, and is one of the founders of the Language Creation Society. Perhaps his best known work is with HBO’s Game of Thrones, where he developed the Dothraki and Valyrian languages. His latest book, The Art of Language Invention, is available from Penguin Books.