When I say “monster,” what do you think about? Frankenstein’s monster? Dracula? The creature from the Black Lagoon? Maybe even Cookie Monster… When we hear that word, we tend to think of monsters from movies or television shows (even when they began as literary characters), and most of the time, they are male. But some of my favorite monsters are female, and most of them have not yet appeared on the big or small screen. They aren’t as numerous as the male monsters, but they are just as interesting.

What is a monster, anyway? We tend to associate the monstrous with the ugly, evil, or frightening, but there’s a more sophisticated way of thinking about these creatures. In On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, Stephen T. Asma argues that monsters are examples of “categorical mismatch.” We like to organize reality into easily understandable categories: you are either male or female, human or animal, living or dead. When something or someone crosses those boundaries, it makes us uncomfortable: that’s when we label it as monstrous. That kind of labeling can be dangerous, because it can allow us to deny someone’s humanity. But the idea of the monstrous can also be powerful. If you’re a woman, it can be a subversive act to think of yourself as Medusa, with snakes for hair, turning men to stone.

Asma points out that the word “monster” comes from the Latin root “monere,” meaning to warn. In other words, monsters always have some sort of message for us. The following female monsters, some of my personal favorites from nineteenth- and twentieth-century literature, tell us that both monsters and human beings are more complicated than we might assume.

Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu

The most famous vampire in English literature is Dracula, but Carmilla is his literary cousin. Bram Stoker was so deeply influenced by Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella that he originally set his novel in Styria, where Carmilla’s castle is located. She is the undead Countess Karnstein who comes to feed on Laura, an innocent English girl. But Carmilla would tell you she is not a monster. She loves Laura and wants to help her become her best self—a vampire. Carmilla is really a love story between two women—something that would have shocked Victorian society, if it weren’t concealed by the novella’s gothic trappings. In the end, Carmilla is destroyed, but she haunts Laura, just as she continues to haunt modern vampire fiction.

The most famous vampire in English literature is Dracula, but Carmilla is his literary cousin. Bram Stoker was so deeply influenced by Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella that he originally set his novel in Styria, where Carmilla’s castle is located. She is the undead Countess Karnstein who comes to feed on Laura, an innocent English girl. But Carmilla would tell you she is not a monster. She loves Laura and wants to help her become her best self—a vampire. Carmilla is really a love story between two women—something that would have shocked Victorian society, if it weren’t concealed by the novella’s gothic trappings. In the end, Carmilla is destroyed, but she haunts Laura, just as she continues to haunt modern vampire fiction.

The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker’s second best monster story concerns Queen Tera, an ancient Egyptian mummy. It was written during a time when English readers were fascinating by archaeological discoveries in Egypt. But it’s also a novel about gender dynamics. A group of English archaeologists want to revive Queen Tera, but it’s obvious that the spirit of Queen Tera is present and controlling events. She has a mysterious link with Margaret, the beautiful daughter of the famous Egyptologist who discovered the mummy; by the end of the novel, she has taken over Margaret and broken free of the men who are trying to control her. (Stoker really liked playing with anagrams: the letters of Tera’s name are also the last four letters of Margaret. Maybe Stoker was hinting that the modern young woman contains a powerful Egyptian queen?) When the novel was reprinted, an editor changed the ending so Queen Tera was defeated and Margaret survived to marry and, presumably, live happily ever after. Evidently, contemporary audiences were not yet ready for the monster to win.

Bram Stoker’s second best monster story concerns Queen Tera, an ancient Egyptian mummy. It was written during a time when English readers were fascinating by archaeological discoveries in Egypt. But it’s also a novel about gender dynamics. A group of English archaeologists want to revive Queen Tera, but it’s obvious that the spirit of Queen Tera is present and controlling events. She has a mysterious link with Margaret, the beautiful daughter of the famous Egyptologist who discovered the mummy; by the end of the novel, she has taken over Margaret and broken free of the men who are trying to control her. (Stoker really liked playing with anagrams: the letters of Tera’s name are also the last four letters of Margaret. Maybe Stoker was hinting that the modern young woman contains a powerful Egyptian queen?) When the novel was reprinted, an editor changed the ending so Queen Tera was defeated and Margaret survived to marry and, presumably, live happily ever after. Evidently, contemporary audiences were not yet ready for the monster to win.

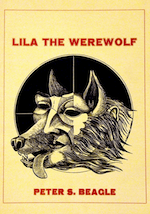

“Lila the Werewolf” by Peter S. Beagle

This short story by Peter Beagle counts as a book only because it was originally published in chapbook form, but it’s one of the classic werewolf tales. Lila is a modern young women living in New York City. After she moves in with her boyfriend, he discovers that once a month, she turns into a wolf—with hilarious and gruesome results. Beagle’s story treats the werewolf theme realistically. As a wolf, Lila devastates the neighboring population of pet dogs. As a human, she has problems with her mother, who both loves her and wants to protect her in an overbearing way. In the end, the monster is not defeated. Although she and her boyfriend break up, Lila goes on to live a normal life—well, as normal as possible, if you’re a werewolf.

This short story by Peter Beagle counts as a book only because it was originally published in chapbook form, but it’s one of the classic werewolf tales. Lila is a modern young women living in New York City. After she moves in with her boyfriend, he discovers that once a month, she turns into a wolf—with hilarious and gruesome results. Beagle’s story treats the werewolf theme realistically. As a wolf, Lila devastates the neighboring population of pet dogs. As a human, she has problems with her mother, who both loves her and wants to protect her in an overbearing way. In the end, the monster is not defeated. Although she and her boyfriend break up, Lila goes on to live a normal life—well, as normal as possible, if you’re a werewolf.

Dawn by Octavia Butler

In Jewish folklore, Lilith was the first wife of Adam, cast out of Eden when she refused to subordinate herself to the first man. She became a demon who preyed on children. Butler’s Lilith Iyapo is a young black woman who has survived the nuclear war that devastated Earth. She wakes to find herself on the spaceship of an alien race called the Oankali, who are gene traders—they trade genes with other races to continually change and adapt themselves to different worlds. The Oankali have three genders—male, female, and ooloi. They have woken Lilith because they want to mate with her to create human-Oankali hybrids as part of the continual evolution of their species. Merging with the Oankali in this way might also help humanity overcome the two traits that, together, have doomed it to destruction: intelligence and hierarchical thinking. In helping the Oankali, Lilith herself becomes part alien, benefitting from genetic manipulation and bearing the first human-Oankali child. When she tries to convince other humans to join with this alien race, they reject her as traitor. Ultimately, however, she helps humanity overcome categorization: the monster points the way to a healthy, productive future.

In Jewish folklore, Lilith was the first wife of Adam, cast out of Eden when she refused to subordinate herself to the first man. She became a demon who preyed on children. Butler’s Lilith Iyapo is a young black woman who has survived the nuclear war that devastated Earth. She wakes to find herself on the spaceship of an alien race called the Oankali, who are gene traders—they trade genes with other races to continually change and adapt themselves to different worlds. The Oankali have three genders—male, female, and ooloi. They have woken Lilith because they want to mate with her to create human-Oankali hybrids as part of the continual evolution of their species. Merging with the Oankali in this way might also help humanity overcome the two traits that, together, have doomed it to destruction: intelligence and hierarchical thinking. In helping the Oankali, Lilith herself becomes part alien, benefitting from genetic manipulation and bearing the first human-Oankali child. When she tries to convince other humans to join with this alien race, they reject her as traitor. Ultimately, however, she helps humanity overcome categorization: the monster points the way to a healthy, productive future.

Tehanu by Ursula K. Le Guin

It seems strange to call Tehanu a monster, when she is most obviously an abused little girl. But like Lilith, she is an example of categorical mismatch: in Tehanu’s case, both human and dragon. In all the Earthsea books, Le Guin is deeply concerned with how we create and maintain borders, and how we can start to overcome our human tendency to categorize the world around us into hierarchical oppositions. The men who abused Tehanu want to maintain power, in part by enforcing traditional gender roles. Both in this book and in The Other Wind, the next book in the Earthsea series, Tehanu helps break down those constructed boundaries. Finally, we learn that humans and dragons are essentially the same—the human and what we consider the monstrous are really one.

It seems strange to call Tehanu a monster, when she is most obviously an abused little girl. But like Lilith, she is an example of categorical mismatch: in Tehanu’s case, both human and dragon. In all the Earthsea books, Le Guin is deeply concerned with how we create and maintain borders, and how we can start to overcome our human tendency to categorize the world around us into hierarchical oppositions. The men who abused Tehanu want to maintain power, in part by enforcing traditional gender roles. Both in this book and in The Other Wind, the next book in the Earthsea series, Tehanu helps break down those constructed boundaries. Finally, we learn that humans and dragons are essentially the same—the human and what we consider the monstrous are really one.

All of these characters can be seen as traditional monsters: a vampire, a mummy, a werewolf, an alien, and a dragon. But more importantly, they are examples of Asma’s categorical mismatch, combining oppositions such as the human and animal, living and dead, self and other. They allow writers to talk about issues such as gender, sexuality, and racial prejudice that might be more difficult to talk about in realistic literature. I arranged these examples chronologically so you can see how female monsters have changed over time, from dangerous femmes fatales to heroines and saviors. We think about monsters differently than we used to, and that’s a good thing.

I’m fascinated by them because growing up, I always identified with the monsters rather than the princesses in need of rescuing. Monsters were powerful and dramatic, and what teenage girl doesn’t want that? But they also had problems—they were outsiders trying to make their way in the human world. Of course I identified with that as well. I wrote The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter because I wanted the female monsters of the nineteenth century, who so often don’t get happy endings, to at least have their own stories, and their own say. We could do a lot worse, I think, than listen to what monsters have to tell us.

Theodora Goss is the World Fantasy Award–winning author of many publications, including the short story collection In the Forest of Forgetting (2006); Interfictions (2007), a short story anthology coedited with Delia Sherman; Voices from Fairyland (2008), a poetry anthology with critical essays and a selection of her own poems;The Thorn and the Blossom (2012), a novella in a two-sided accordion format; and the poetry collection Songs for Ophelia (2014). She has been a finalist for the Nebula, Locus, Crawford, Seiun, and Mythopoeic Awards, as well as on the Tiptree Award Honor List, and her work has been translated into eleven languages. Her newest book, The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter, is now available from Saga Press.

Theodora Goss is the World Fantasy Award–winning author of many publications, including the short story collection In the Forest of Forgetting (2006); Interfictions (2007), a short story anthology coedited with Delia Sherman; Voices from Fairyland (2008), a poetry anthology with critical essays and a selection of her own poems;The Thorn and the Blossom (2012), a novella in a two-sided accordion format; and the poetry collection Songs for Ophelia (2014). She has been a finalist for the Nebula, Locus, Crawford, Seiun, and Mythopoeic Awards, as well as on the Tiptree Award Honor List, and her work has been translated into eleven languages. Her newest book, The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter, is now available from Saga Press.