I came into my queerness late in life. Well, later, at any rate, than the teenagers I wrote about in my sapphic YA fantasy, Sweet & Bitter Magic. Yet after I learned that my heart was not surrounded by a wall, but rather, a gate just waiting to be opened, after I met the woman who is now my wife, as I explored the world of women who love women, I realized there had always been something inherently sapphic about the way I had lived my life.

There are no shortage of ways people attempt to explain away the existence of sapphic couples: “best friends,” “roommates,” “gal pals,” “sisters” are only a few of the ways strangers have tried to classify the familiarity, love, and safety present in my marriage. And strangers are so desperate to identify us that once, after a quick shutdown of “we’re not sisters,” someone moved on to a hesitant “so you’re… co-workers?”

I am privileged enough that I didn’t have to shy away from this new, complex piece of myself. My coming out was straightforward enough, the wedding guest list only slightly culled. But I’ve still been afraid while walking down the street with my wife, hesitant enough that I decided against a kiss, or intertwined fingers. I’ve been berated by strangers, slurs hurled in a way expected to break me, rather than to bloom the sort of dark-petaled resentment that permanently resides in my chest: I will always have to be just a little bit afraid.

Still, when it came to my writing, the first thing I wondered was: what might it be like to be free of that fear? If, in fantasy worlds, witches cast spells and dragons breathe fire and swords build legacies, maybe here, finally, is where a woman can live, happily ever after, with another. And it is within fantasy that I finally found that freedom, that space to explore the way a sapphic relationship might exist without the inherent social and political obstacles present in our world.

In the kingdom of Rabu, the setting of Nina Varela’s Crier’s War, a war rages between humans and automae. Crier, a girl who is “Made”, and Ayla, a human girl, are the definition of enemies to lovers—two girls existing within opposing factions. Yet this enmity—the force keeping them apart—has nothing to do with the content of their hearts. Instead, there are specific military and political tensions that exist in this fantasy world, separate from the political and social issues that are prevalent in our day-to-day lives. This escapism allows full investment in the story, in both Crier and Ayla’s choices, because the undertones of our reality do not exist here, in a war of human versus machine. It is also within this divide that readers find what makes Crier’s and Ayla’s love all the more earnest. Their attraction specifically works against their two very different goals and self-interests, but those hurdles make this ship all the more worth rooting for.

There is a tenderness in the way women love women, but a bite, too. There are carefully chosen words, the impossible precision of pining. Absolute, unbridled hunger. Not every sapphic relationship is a soft and tender slow-burn. Women who love women have a wide spectrum of emotions, and the way they enter into relationships is as complex and intricate as every cis-het trope that has ever been represented on page. But there has not always been the freedom to allow sapphic relationships the room to grow and develop where both the main character and the love interest are more than just their sexuality.

In Melissa Bashardoust’s Girl, Serpent, Thorn, protagonist Soraya claims the role of monster. Cursed to poison anything she touches, she lives a careful, cautious life, isolated and alone. But when she meets Parvaneh, a parik, she finds comfort in the company of another monstrous girl. With Parvaneh, Soraya finally feels human. As Soraya searches for a way to end her curse, Parvaneh is her constant—her guiding light, her confidant, and her reminder that sometimes, the pieces of ourselves that seem the most monstrous hold the greatest power.

This is why it is so powerful when sapphic-helmed fantasy does exist. There’s a difference in a sapphic character’s navigation, a difference in noticing, a difference in the way a partner is considered, a difference in how love is presented, protected, and shared.

In Marie Rutkoski’s The Midnight Lie, Nirrim finds power in her attraction to Sid, the mysterious girl she meets in prison. Power not only in the freedom of giving into her desires, but literal power, as well. Her relationship with Sid expands her life from a small sector of the Ward to the world beyond the wall, places in Nirrim’s own country she would never have been brave enough to enter were Sid not her motivating factor. The relationship and care between the two girls emboldens Nirrim to revaluate her past relationships, to begin to question the way other people in her life treat her as property. With Sid, Nirrim finally finds a partner who treats her as a true equal, and it is because of their relationship that Nirrim learns to embrace every piece of herself.

There’s also a difference in the presentation of a character’s sapphic nature on page when they exist in a world that has never shamed them for their heart. They may be judged for other behaviors, other decisions may put them in the line of crossfire, but there is something incredibly powerful about a sapphic character who simply exists in their queerness rather than continuously having to justify it. When queerness is taken as simply one part of a larger whole, sapphic girls can explore something beyond just their queerness.

In Mara Fitzgerald’s Beyond the Ruby Veil, the main character, Emanuela is a power-hungry, ruthless girl, hoping to enter into an arranged marriage with her best friend, not for love but for the connections and position his family holds. Yet Emanuela is never villainized for her sexuality, the way that so many villains are queer-coded. Her selfish actions never have anything to do with her queerness, and instead, some of the most human moments we see from Emanuela are when she interacts with Verene, the girl who is her rival.

These are the books I crave, the sprawling, fantasy worlds that open their arms to my heart. Books that could not exist were it not for the sapphic identity of its characters.

Kalynn Bayron’s Cinderella is Dead is another example of a fantasy where the plot is driven specifically by Sophia’s sapphic nature. Sophia’s love for her best friend Erin means she cannot fathom a world where she bends to the whims of Lille’s king and the way he has twisted Cinderella’s story to benefit himself. Sophia’s rebellion, her desire to seek the truth of the fairytale’s origin, her relationship with Constance, all of these pieces are inherent to Sophia’s sapphic nature, and because of it, the reader is pulled into a high-stakes fantasy world where Sophia is the one who gets to dictate her happily ever after.

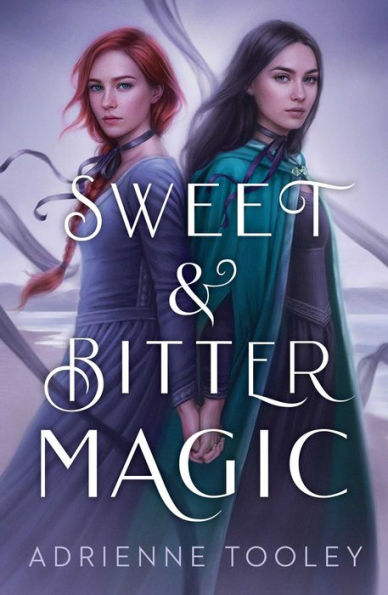

On the cover, of Sweet & Bitter Magic, my two main characters, Tamsin and Wren, are holding hands. The first time I saw the art (by the incredible Tara Phillips), I was on an elevator and kept my tears contained until I got outside. Then, I sobbed next to a mailbox while New York City carried on around me. There was power in the quiet defiance of that act. Resilience and strength in that pose, front and center, on a book that featured those girls falling in love. Right from the front cover, there is never any doubt the story that lives inside.

Buy the Book

Sweet & Bitter Magic

Reading and writing sapphic fantasy brought me freedom I’d never had before outside of my own relationship. It allowed me to navigate the waters of what it meant to me to be a queer woman, without the added pressure of my friends or family or strangers, or, even, my wife.

Will I always carry that dark, blooming fear in reality? Perhaps. But knowing there are places where my love not only exists, but is celebrated for its existence, where characters who love like I do are not punished for the nature of their heart but are are allowed to revel in their queerness without constantly having to justify and claim it, is a breath of fresh air. And so, even if there are some moments with my wife where I’m unsure if it’s safe to hold her hand, I know the girls on my cover will never let go.

Adrienne Tooley grew up in Southern California, majored in musical theater in Pittsburgh, and now lives in Brooklyn with her wife, six guitars, and a banjo. In addition to writing novels, she is a singer/songwriter who has currently released three indie-folk EPs. Her debut novel, Sweet & Bitter Magic, is out now. Her second novel, Sofi and the Bone Song, will release in 2022.