As far as can currently be determined, we are the only technological civilization in this universe…at least the only one of which we are aware. There are many explanations as to why this would be so. The explanation that sparks the plot in the following five works is that of a great filter—some reason that any life that emerges elsewhere will fall prey to some kind of bottleneck and stagnate or die before it reveals itself to our instruments. This essay focuses on one proposed bottleneck: intelligent tool-using.1 Put simply, bright tool-users are better at creative disruption than they are at foreseeing and surviving the consequences.

This explanation gives humanity an excuse for our possible self-extinction (whether due to climate change, nuclear war, death by microplastics, etc.). Calamitous misjudgment isn’t a uniquely human flaw! It’s inherent to tool-using intelligence itself. At worst, we’re just a demonstration case.

Toolmaker Koan by John C. McLoughlin (1987)

On discovering what appears to be an alien artifact at the edge of the Solar System, the United People’s Democratic Republics of Africa and Eurasia hastily dispatches an expedition. Not to be outdone, the Greater Columbian Alliance launches its own spacecraft towards the artifact. Both ships are heavily armed. Determined to prevent their enemy from gaining a monopoly on alien technology, both crafts attempt surprise attacks. This leaves both terrestrial ships irreparably damaged and the surviving crews dying of radiation.

The novel is prevented from being a depressing novella thanks to the intervention of an alien artificial intelligence that the novel calls Charon. Billions of years old, Charon has ample proof that toolmaking species are their own worst enemies, invariably causing their own extinction with misapplied ingenuity. Charon has a bold plan to assist humanity to avoid otherwise inevitable doom. It’s too bad for humanity that the unfortunate AI is quite mad and that its plan cannot possibly work as envisioned.

Normally I tackle theme books in order of publication. In this case, McLoughlin’s novel is what got me thinking about this particular solution to the Fermi Paradox. While the novel has its flaws (stodgy writing, a love of infodumps that would astonish Poul Anderson), there are some genuinely original ideas in the book that reward consideration. Pity the novel is very much out of print.

“Adam and No Eve” by Alfred Bester (1941)

Determined to reach the Moon, a bold inventor deploys his breakthrough discovery, a catalyst that releases energy from the atomic conversion of iron. This will power his rocket!

Now a considerable fraction of the Earth’s mass is iron; if even a drop of catalyst were to escape from the rocket, apocalypse would result. The determined explorer assures nay-sayers that he has taken every reasonable precaution. The launch goes as planned. Almost.

All life on Earth having perished in the ensuing cataclysm, only life off Earth—specifically the explorer and his unfortunate dog—survives. One man alone cannot repopulate a planet with more of his own kind. He might, however, provide the seeds from which a new biosphere could arise.

In his defense, our hero was an ingenious fool. His invention belongs to a class of technology I’ve mentioned before, power sources that should under no circumstances be used near a planet. See also Steve Gallaci’s Albedo, whose total conversion power system could potentially convert entire planets to energy, which would be bad.

Aniara by Harry Martinson, translated by Stephen Klass & Leif Sjoberg (1956)

As depicted in Martinson’s 103 cantos, the tale begins with a refugee ship spacecraft, fleeing radioactive Earth for Mars, that is inadvertently diverted into interstellar space. An alarming development but hope is not dead. Not only are the craft’s systems able to sustain life indefinitely, the Aniara’s nearly omniscient guiding intelligence, Mima, is in constant contact with human civilization.

Humanity learned its lesson from World Wars One through Thirty-Two. What it learned was how to stage wars of increasing destructiveness…until no human remains to fight them. The spectacle is too much for poor Mima, who falls silent. It remains for its passengers to recapitulate human folly on a much smaller but equally doomed scale.

Yes, it is a bit odd that two unrelated works would feature kindly artificial intelligences driven mad by their creators needlessly self-destructing. Proximity to humans is often challenging for benevolent AIs; take for example 2001’s HAL, who only wanted to carry out all of its directives. Aniara stands out because it’s a long poem, and because it was written by a Nobel Laureate.

Sea Siege by Andre Norton (1957)

Griffith Gunston, son of prominent naturalist Dr. Ramsay Gunston, accompanies his dad to the small island of San Isidore, there to investigate the Red Plague currently killing fish. Locals blame sea monsters. This would be laughable were it not correct, as the naturalist soon discovers.

While this research is ongoing, the Cold War goes very, very hot. Most of humanity dies; only a few outliers, like San Isidore, survive. It’s too bad for the humans on San Isidore Island that the new-found intelligent octopuses are actively hostile to their land-dwelling rivals.

On first reading this book, and on re-reading it, I’ve wondered if World War Three was unintentionally provoked by octopus raids on ports. Norton leaves that possibility open.

Requires a “1950s treatment of Islanders has not aged well” warning, although this book isn’t quite as egregious as Norton’s Voodoo Planet.

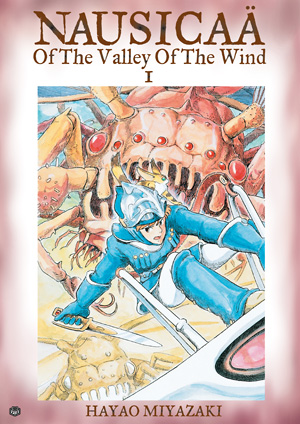

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind by Hayao Miyazaki (1982)

A thousand years after the Seven Days of Fire ended mechanized civilization, the Sea of Corruption covers most of the land. Implacably hostile to human life, the Sea of Corruption relegates the few surviving human nations to small refugia along the edges of the Sea. Plucky heroine Nausicaa’s native Valley of the Wind is one such refuge, protected by winds and human vigilance from the spores of the Sea.

Humanity is much reduced but just as greedy. When the Torumekians attack the Doroks, the Doroks respond with weaponized Sea of Corruption spores. Success! The Torumekians are no longer the primary threat facing a rapidly dwindling number of Doroks. Invasion foiled! All it took to prevent it was triggering an apocalyptic disaster.

Nausicaä is odd in that individual humans (like Nausicaä) are noble, brave, and likable, but the species to which they belong is irredeemably corrupt. As the increasingly unhappy protagonist discovers, The Sea of Corruption is a misnomer. It is not corruption at all but rather the means by which nature purifies itself. Too bad for humanity that humans are deemed contamination.

***

Humans (and intelligence in general2) being deemed by many authors a regrettable development, there are many works I could have mentioned (and may have in previous essays) but did not. Notable examples of tool use as a self-solving problem may be mentioned in comments, which are as ever below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]Of course, this raises the question of what we mean by detectable. If, for example, we were to discover hundred-million-year-old relics of a long-vanished dinosaurian civilization, does that count as detection?

[2]Project Itoh’s “Harmony” is an interesting edge case, in which the problem in the view of one character is not intelligence but consciousness. Human suffering is rooted in their awareness of their circumstances. Finding the off-switch for self-awareness would not make people happy, but it would make it impossible for the resulting living automatons to be unhappy. I should perhaps note that Project Itoh, who was terminally ill when he wrote “Harmony,” was not an upbeat person.

Brust’s 500 Years After works too.

I’m fairly sure that any future biography of one James Davis Nicoll would be a work “About Intelligent Beings Who Are Their Own Worst Enemies”.

There was a SF story I read a few years ago where paleontologists discover breakdown products of Plutonium just below the K/T boundary. Also plastics. Background of the story is rising tensions between modern superpowers. Wish I could remember where I saw it

2: In my defence, my conception of that bonfire included neither the fuel-air explosion in which I was enveloped, nor my surprising flammability.

Wile E. Coyote.

‘Nuff said.

Forbidden Planet: And about once a month, Star Trek would encounter a planet or a space probe whose organic patrons are not around any more for reasons very important to determine, often military. Either James Blish’s version or the filmed script of episode “Return to Tomorrow” had the big glowing ball aliens explain that Earth’s Third World War is only the first Great Filter of civilisations, and the ball people had run into the second, which is why they are now balls on shelves in storage on a very dead planet. It may have been the same Filter as “Forbidden Planet”.

Isaac Asimov: Silly Asses, though it is a short story it hits the point.

Álbedo: to say the conversion reactor would have catastrophic effects is an understatement: the results of one going out of control on a planet would be something like a biggish supernova, imperiling star systems dozens of light years away.

It’s worth noting the technology is evidently developed in one series, but it’s effects are outlined in another one. One set considerably later, where the previous interstellar confederation has disappeared, to be replaced by a loose coalition of planets. They are united in at least one thing: inhabited planets have orbital weapon satellites pointing at them, armed with enough firepower to glass the planet if someone shows signs of conducting dangerous experiments. Almost as of they’ve had an unfortunate experience or two…

3: That sounds like a Nature Magazine Futures (their one-page stories feature) that I read a few years ago. But not sure how to find it; the Futures web pages gives not-very illuminating one-sentences precises of each story and one would have to sort through each one.

Well, Mary Gentle’s Ancient Light, the sequel to Golden Witchbreed, would seem to count. In that book, as I recall from reading it a few decades back, a species manages to render inhabitable the only planet on which it can live. In this endeavor, it is assisted by a tiny remnant of a nearly-extinct progenitor species, the Golden Witchbreed of the title to the first book in the series.

Poul Anderson’s novels of Flandry of Terra involves a government agent (spy) doing his best to prop up a slowly-declining culture. As the decline is largely brought about by its own inaction, I feel that it counts here.

I would mention Túrin in the Silmarillion, whose self-inflicted problems are well-documented in Jeff LaSala’s article “A Series of Unfortunate Choices (Made by the Children of Húrin)” on this website. However, it seemed to me we were more interested in SF than in Fantasy, so instead I will point to Harry Harrison’s Deathworld 1, the first of that trilogy. In this novel, the protagonist Jason DinAlt discovers that the problems of the titular planet are largely self-inflicted; they have managed to turn the entire ecosystem against them. By working with another group of colonists who have learned to make peace with the local life, he is able to forestall the worst consequences, however.

Footnote 2 reminds me of Peter Watts’ _Blindsight_, which involves a (sort of) first contact with beings that probably qualify as intelligent tool-users, but do not possess “consciousness”. Given the events of the sequel, it is strongly implied thay consciousness is a mal-feature that has doomed humanity.

On a different note, I guess now I know what the “Aniara fleet” in Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep is a reference to… Here I has always thought it was some in-universe event, rather than a literary reference.

That’s the most depressing of the many possible answers I’ve seen to the Fermi paradox. Thankfully, unless another depressing set of answers is true, that the development of multicellular organisms, possibly of life at all is vanishingly rare, there should be at least millions, more likely billions, of intelligent life forms that exist or have existed in the universe. I’d have to rate the probability that ALL of them fail the toolmaker koan as indistinguishable from zero.

My preferred answer is that humans are technologically advanced and intelligent approximately on a par with chimpanzees fishing for termites with twigs. In other words, from a galactic viewpoint, the answer to “Is there intelligent life on Earth?” is “no.”

@3 Tanya Huff Peacekeeper series

@13

The most likely answer to the Fermi question is that space is big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. It’s actually even bigger than that. There could be billions of tool-making species out there and still not be another one in the same galaxy as us. It’s a long, long, long, long, long way to absolutely anywhere else, and it’s turning out to be harder to cross that distance than the optimists of Fermi’s day guessed. (Yes, part of that is resource allocation, and is, say, the US had for some reason decided to pump hundreds of billions of dollars into NASA contractors instead of military contractors (S.M. Stirling’s Lords of Creation duology give the reason that early probes discovered life on Venus and Mars, due to the titular precursors, so the Cold War arms race became a space race, and there are US and Soviet bases on both planets in the ’80s, but also they don’t need to worry about life support on planet, so that’s much easier), but space travel is fantastically difficult, even on an engineering basis, and getting anything crewed up to a significant fraction of c just isn’t on yhe table in the foreseeable future). Signal degradation over distance is also much greater than expected; there won’t be any alien civilizations picking up our broadcasts, because they’re hash effectively indistinguishable from background radiation by the orbit of Saturn. By the same token, we’re not going to hear anyone out there unless they’re pointing a fantastically powerful narrowcast directly at us. Which they would have no reason to do, because they can’t hear us.

A Canticle For Leibowitz.

This one might be a bit of a stretch but “Tuf Voyaging”, Martin’s brief foray from swords and dragons has the hero inheriting an advanced interstellar eco-lab with devastating capabilities. Also in Nivens known space collection there is a UN contingent that is responsible for monitoring and suppressing any technologies that may potentially wipe out humanity. The idea of a cosmic filter that ensures emerging civilizations either achieve the necessary wisdom to manage their destructive impulses or perish as a result of failing to do so, seems to me to be an extrapolation of Darwin’s survival of the fittest. The fittest, in this sense, are those species that develop the required ethical morality to conquer their primitive instincts and cultivate their better angels. If an artificial general intelligence emerges from humanity’s reckless tinkering, we may, once and for all, answer the question of whether greater intelligence is automatically accompanied by a greater ethical philosophical cosmology.

I assembled a blue ribbon ethics committee made up of Colossus, P1, Skynet, HAL 9000, and Allied Mastercomputer and all of them agree it can often be ethical to kill all humans.

Then there is the possibility brought up by Donna Barr (artist+writer of The Desert Peach and the Stinz comics) that the reason we aren’t detecting anyone else ‘out there’ is because we are the first. ‘After all, somebody has to be the first. Why not us?’ Terribly humanocentric? Maybe. Or maybe just terrifying. What if we are ‘the first space-faring civilization’?

Then humanity as a whole gets to play the role I do at work, the wise elder figure who helpfully prepares the younger ushers for life in 1985.

@19: we live around a ~4-billion-year-old very ordinary sun in a universe ~14 billion years old; the likelihood that we are first seems infinitesimal to me.

@21; But during the first long stretch of that time, there were no, or at least very few, elements heavier than helium in the universe. Not until the first few generations of stars lived and died, and their “ashes” formed new stars, were there the materials needed for solar systems, and possibly life is very hard to come by without higher-order elements that require other, even less common, events.

For example, many of the elements on the Periodic Table formed in whole or part due to collisions of neutron stars, which I seem to remember reading somewhere¹ didn’t happen until the third or fourth generation of stars. Google the phrase “element origins neutron stars” or some similar collection and you should find tons of information. It’s really amazing stuff.

Also, the formation of land life may depend on a truly improbable accident, namely the formation of Earth’s unusually large (relatively speaking) moon. For more on this, you could consult, e.g., Asimov’s science article “The Tragedy of the Moon.” It is difficult to conceive of aquatic life being capable of interstellar communications, even granted that it can imagine it.

If you, like me, are a Drake-equation groupie, then you already know much of this, and I apologize for lecturing you on a subject you undoubtedly already know about.

¹Half of the interesting facts in my memory can’t be sourced more accurately than that; I’m sorry.

ISTR that the “long stretch of time” was a lot less than half the estimated life of the universe — that the first generation(s) of stars lived fast, died young, and left useful corpses, such that there would have been many suns like ours by the time ours started coalescing. I haven’t been following enough details of research to know whether this estimate has changed substantially in recent decades. I looked at the number of assumptions in the Drake equation and concluded that it wasn’t useful; possibly another decade’s results from the Webb telescope will give substance to a few of that handful of coefficients. I vaguely remember “The Tragedy of the Moon” (and its sequel — “The Triumph of the Moon”?) having more to do with the development of science than the development of plate tectonics; given how long ago that essay was (and that Asimov himself had ridiculed the idea of plates earlier in his career), I doubt that it has any more relevance than Niven’s early (passed-on?) theory that Earth would have been another Venus without a moon big enough to stir up the atmosphere.

As I recall (from far too many years ago shut up about it), one of the propositions in ‘The Tragedy of the Moon’ was that without the extensive tides due to the size of Luna, life would not have colonised the land from the ocean (i.e., some stuff getting washed up onto the beach and surviving).

Solar tides are about a third as strong as lunar.