The earliest mentions of fabled lost Atlantis were, as you know1, in two essays by Plato, Timaeus and Critias. The context of these mentions suggests that Plato invented Atlantis out of whole cloth, as an illustration of certain philosophical points. However, many have wondered if perhaps Plato had some real-world basis for his Atlantis. Others, Ignatius L. Donnelly for example, have firmly insisted that Plato did.

Cynics might object that any mentions of Atlantis after Plato wrote were clearly derived from his essays; there are no mentions of Atlantis in other contemporary sources or in any previous sources. There is no physical evidence of an island such as Plato described or of any Atlantean empire.

And yet… authorities such as Donnelley, Blavatsky, and Pournelle have asserted that Atlantis was real. Shouldn’t this count? Why, if we doubted the historical reality of Atlantis, we might as well disbelieve in the historical reality of Oz, Winnemac, and Narnia!

Archaeological questions aside, the central idea of Atlantis—an ancient, highly advanced civilization whose stupendous achievements could not in the end save it from doom—has been an inspiration to many authors. Consider the following five works.

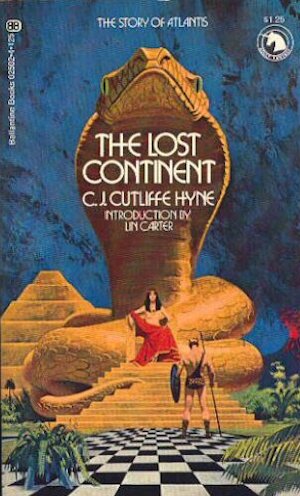

The Lost Continent by C.J. Cutcliffe Hyne (1899)

Although of lowly birth, Phorenice is brilliant, opportunistic, and lucky. Through fortuitous adoption, martial prowess, and a determined disregard for tradition, she has seated herself quite firmly on Atlantis’ throne. She is that great land’s first empress. Alas, Phorenice’s hubris may well doom Atlantis, by civil war or divine wrath.

An empress needs a consort. Phorenice makes the cold-blooded calculation that Deucalion, paragon of Atlantean virtue, would be an ideal consort. Good news for Atlantis: Deucalion could guide Phorenice away from certain disaster. Better news for Atlantis: Phorenice, to her surprise, falls in love with Deucalion. True, Deucalion is in love with someone else… but that is a trivial matter easily resolved by ordering Deucalion to murder the woman he loves. What could possibly go wrong?

Hyne’s novel is notable for two things. First, it’s a very early example of a common Atlantean trope: teasing readers with the possibility that Atlantis will be saved from certain doom, then ending with Atlantis’ watery apocalypse. Second, the novel’s framing sequence features the most appalling depiction of careless Victorian-era desecration of irreplaceable relics that I’ve ever read.

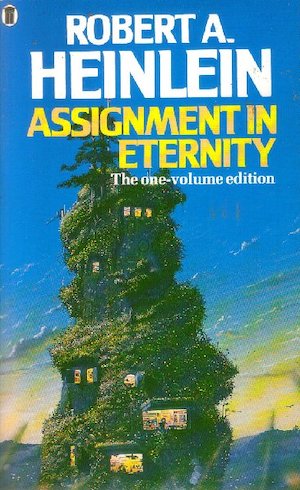

Lost Legacy by Robert A. Heinlein (1941)

While hiking with his chums on Mount Shasta, Dr. Philip Huxley breaks his leg. Things look dire; Phil could die of exposure before his friends can bring aid. Fortuitously, a stranger appears to provide Phil with much-needed medical care.

The stranger reveals himself to be Ambrose Bierce. He claims to be a member of a secret society of psychic adepts whose arts hark back to ancient Atlantis. Phil and company would be perfect recruits.2 The catch? There are those who do not want humanity to regain its lost godlike powers, people who will go to great lengths to prevent such a development. By joining Bierce, the young Americans sign up to take part in a war for humanity’s soul.

A question I blame Alec Nevala-Lee’s Hugo-finalist book Astounding for making me ponder: was Heinlein channeling the views of noted rocket scientist/occultist author Jack Parsons? Or was RAH simply drawing on the occultism in which everyone seems to have been steeped back then?

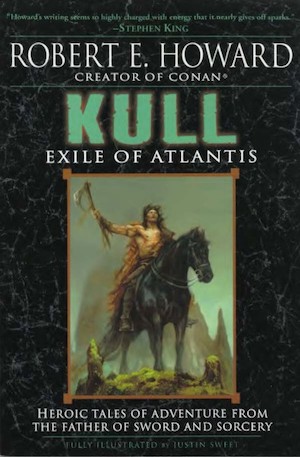

“Exile of Atlantis” by Robert E. Howard (19673)

Long before Atlantis was glorious, it was a patchwork of barbarian tribes, each more violent and superstitious than the next. Kull, lone survivor of his people, had the good fortune to be adopted by Gor-na’s tribe. Kull has the physical prowess to be a great man of the tribe… if only Kull could somehow smother his impious skepticism concerning his new tribe’s manifestly absurd customs and beliefs.

Matters come to a head when Kull discovers a young woman is to be burnt alive for violating marriage law. The future King of Valusia faces a choice: do nothing about the cruel and unjust execution and be accepted by society, or act and face exile.

Kull is in some senses very much like Conan, with one very important difference. Kull is far more introspective than Conan. As a result, Kull is often far more miserable than Conan, plagued as Kull is by perplexing philosophical dilemmas. The moral is probably that you can never go wrong overthinking things.4

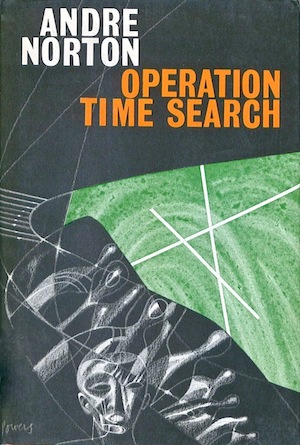

Operation Time Search by Andre Norton (1967)

Photographer Ray Osborne reveals a heretofore unestablished use for Hargreaves and Fordham’s time-viewing technology when Osborne blunders into one of their tests. Osborne is transported to an old-growth forest unfamiliar to him. Soon after that, Osborne is captured by Atlanteans.

The ancient world in which Osborne finds himself is divided between virtuous Mu and very much not virtuous Atlantis. Worse, Atlantis now has the means to win the long struggle against Mu. Can American pluck and a near-total lack of operational security on the part of Atlantis save the day? Or, like Plato’s Atlantis, will Atlantean hubris ensure catastrophe?

It’s not clear whether Norton’s Atlantis is Plato’s, and therefore in the distant past, or a realm in a parallel universe that happens to be very similar to Plato’s Atlantis. What’s even less clear is exactly what happens at the end of the novel. Did Osborne save Atlantis and Mu from immersion, somehow without affecting history? Or did something even less likely happen?

The Dancer From Atlantis by Poul Anderson (1971)

A malfunctioning time machine clearly out of warranty scoops up American Duncan Reid, Kievan Russian Oleg, Hun Uldin, and Minoan Erissa from their native eras, and deposits them in the past. The time traveler who accidentally time-napped the quartet barely has a chance to choke out a surprisingly detailed infodump before perishing of his wounds. The four are, it seems, trapped in the past.

Erissa comes from a time closer to the one where she ended up. She can tell where they are: not too far from an island known to fellow Bronze Agers as Atlantis. As to when they are? The days immediately before volcanic disaster snuffed out Atlantis and upended civilization across the Mediterranean.

Is history fixed? Or can Duncan and the others do anything about a foreordained calamity that underlines how ephemeral everything good and valuable is? I regret to report that Poul Anderson in his most gloomy period is not the author to turn to for what Tolkien termed “eucatastrophe.” Still, The Dancer from Atlantis is more upbeat than Anderson’s “The Pugilist.”

Factual or not5, Atlantis has been an inspiration to many authors. The above is only a small sample. I didn’t even mention the role Atlantis played in the Perry Rhodan novels or the eyebrow-raising Jane Gaskell novel Some Summer Lands. Perhaps you have Atlantean favorites not mentioned above. If so, extol them in comments below.

- Bob.

- Yes, it is tremendously lucky that the hikers Bierce rescues are perfect candidates for enlightenment, to the point that one has to wonder if Bierce orchestrated the accident as a meet-cute. Still, either the hikers would be perfect or they would not be, so 50/50 odds, right? And there’s a story in the encounter either way.

- Howard died in 1936. As a general rule, authors’ work tends to be written prior their death. The 1967 denotes when the story was first published.

- True story: in 2016 or so, my boss told me not to overthink things. I waited five or six years, then assured her I had come up a 128-step process to determine if I was overthinking something. A week later she realized I was joking.

- Not.

Unearthing Atlantis by Pellegrino is a good overview of the Minoan/Atlantis theory and the archaeology behind it.

I never heard of that Heinlein.

Niven’s “Magic Goes Away” series has Atlantis stories, or at least mentions Atlantis.

And of course Doc Smith has Atlantis in one of his Lensman books.

I think perhaps the in-text link to footnote 2 is missing and as result all the footnotes after the first are misnumbered: what you have as 3 is actually 2 and so on.

Should be fixed now. Thanks!

In The Face in the Abyss, A. Merritt finds the refugees from Atlantis in the Andes mountains, where they have created a high tech civilization, Yu-Atlanchi, along with refugees from the Incan empire and descendants of intelligent dinosaurs. And have managed to remain undetected by the rest of the 1930s great powers.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Akallabeth, in which the King of an island realm far off in the ocean discovers that just possibly prisoners of war are not reliable guides to the lands of their enemies. I am given to understand that when Tolkien figured out the Quenya name for post-fall Numenor, he realized that “the Downfallen” translated to Atalante, which came as a surprise to him.

J. R. R. Tolkien, “The Akallabeth” (published as part of “The Silmarillion”) where Tolkien shows he’s a sucker for an Elvish-English multilingual pun.

I’ll throw in the Japanese movie “Atragon”, had some sort of war between Atlantis and Mu. I just loved the movie because Atragon was your full-service submarine, also with a big drill in front for swimming through rock. I’m not sure how it flew, there were no wings, but it did.

Haven’t seen it in 60 years, roughly, no idea how one could. But I’m not making it up, it’s in the IMDB.

It’s awesome that Calgary still has the Plaza theatre, about 50 years now as a repertory “Casablanca” cinema. But this is when it was regular neighbourhood cinema, with 35 cent Saturday movies, and 50 cents for a double feature.

Just had to drop that memory.

Am I a terrible person for now contemplating writing a story in which intrepid time travellers visit a very real Atlantis, only to discover subsequently that Plato is entirely fictional?

Plato was made up for the sake of Socrates’ ego. Socrates never wrote anything down, because all.his writing was done in the character of Plato, who was always amazed at how brilliant Socrates was. Not unlike modern cases where a cheerleader of some prominent internet personality has turned out to be said personality posting under a fake name

Do you mean the type of story where a time traveller discovers that [Famous Person] never really existed, wherefore, the time traveller is obliged to “be” [Famous Person]?

Instances:

“Behold the Man”

Er… not sure about others. I think there’s one where a time traveller has to replace Julius Caesar? But Caesar was real, but he died. Or maybe he got better in the end. Clearly, I don’t remember.

Someone’s done Shakespeare, they must have. Isaac Asimov did the one where someone brings Shakespeare into the 20th century and to an English literature class, which he fails.

One of Poul Anderson’s Time Patrol stories, where a Patrolman found himself stuck in the role of Cyrus of Persia.

The plot of Illuminatus!, insofar as it can be said to have one, relies heavily on secret societies and rivalries stretching back to Atlantis, but it was also a deliberate send-up o the kind of occultism espoused by Parsons etc, among other things.

It’s been decades since I read John Jakes’ Mention My Name in Atlantis, but IIRC in it Atlantis is just another place, not particularly special. Of course it’s supposed to be a humorous book.

Do stories in which Atlantean society survives somehow beneath the waves through magic or superscience count? If so, there’s Lester del Rey’s Attack From Atlantis. If not, there’s one suggestion for a follow-up article.

Folk rock singer-songwriter Donovan has a song about Atlantis, but it’s mostly a long and tedious spoken word ramble.

From what I remember of “Lost Legacy”, by the time Phil breaks his leg he and his friend (and the woman who is mostly there to say at the end “The war’s over! I can get married!”) have made serious progress into the mystic arts — everything from telepathy to determining the outcome of a game of solitaire by a quick riffle through the deck — which may have brought them to the attention of Bierce-et-al. (either generally or by telepathic distress at the accident). ISTR that they were climbing in that particular place in answer to a vision, which may have come from B-e-a or from their expanded perceptions that this particular mountain had reason to be connected to mystic legend. I had forgotten how early this one was; it may have been connected to Parsons, or it may have answered one of Campbell’s desires. (JWC had so many … enthusiasms … that I’ve forgotten when he was pushing what, but mental superpowers were high on the list for some time.)

Re: that Pournelle link, I do actually have a copy of 2020 Vision on my bookshelf now, although I don’t think I have opened it this century

Atlantis is mentioned in C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, as the origin of the box of dust that Uncle Andrew made the magic rings from.

In Yudkowsky’s Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, the use of magic originated in Atlantis, and was most powerful there. It has supposedly been weakening ever since, with the blood purists believing that that was due to interbreeding with Muggles.

How could I have forgotten Man From Atlantis?

I suppose someone (and since no one else has, it falls to me) ought to mention that both Marvel and DC comics have versions of Atlantis, both of which have miraculously survived under the sea (cue crab) all these millenia. Marvel’s Atlantis is the home of Prince Namor, the

SubmoronSub-Mariner; DC’s is the home of Aquaman, who was always the most boring character in the Justice League when I was a kid……Justice League and Avengers missions tend to be set on land. Atlanteans are very likely to be involved if the mission is in the two-thirds of Earth that is under the sea.

Marvel’s underwater Atlantis has been destroyed and re-founded a number of times over the years, though I’m not absolutely sure that the number is greater than 1.

For instance, a now former “New Atlantis” was constructed in San Francisco Bay and was the base of the column on which Utopia Island stood, being where the X-Men were living at that time. I don’t remember if this location is earthquakey or was said to be. Utopia Island did have a stability problem before the sea-folk got involved.

Atlantis was destroyed by the machinations of the crazed Professor Zaroff in the Doctor Who story “The Underwater Menace”.

Atlantis was also destroyed by the Chronovore Kronos in the Doctor Who story “The Time Monster”,

And Azal, the Daemon, claims to have destroyed Atlantis in the Doctor Who story “The Daemons”.

I think the message here is that Doctor Who villains really, really don’t like Atlantis.

Nesbit’s Story of the Amulet has a chapter visiting Atlantis.

“To just outside Atlantis,” said Cyril, and Jane said the Name of Power.

“You owl!” said Robert, “it’s an island. Outside an island’s all water.”

“I won’t go. I won’t,” said the Psammead, kicking and struggling in its bag.

There’s Atlantis Found by R. Garcia y Robertson. I bought and read it when it came out but I can’t remember anything about at all (Sorry R., if you’re reading this post). Maybe I should brave the basement to see if I can find it.

If I eecall correctly (it’s been a long time since I last reread the series), Patricia Kennealy-Morrison’s Keltiad novels set up a back story in which the Keltic peoples are space aliens who colonized Earth very early in human history, founded Atlantis and its Pacific counterpart, and left again in the wake of early Christian persecution when a certain Brendan builds a spacecraft instead of a boat in ancient Ireland.

Jo Walton’s The Just City is set on the island of Thera in the distant past. In the book, time travel is used to create the perfect society of Plato’s Republic. Putting it on Thera is not only a nod to Plato’s stories about Atlantis, it also is convenient to let the volcano erase any trace of the experiment. Of course, things don’t work out exactly as planned. But it’s a good story.

Atlantis turns up in a fantasy novel from just a couple of years ago, by a three-time Hugo novel award winner.

In older SF, Isaac Asimov used a horrible pun to destroy Atlantis (a real shaggy dog story), and Brown had Atlantis as one of many previous civilizations in “Letter to a Phoenix”

Atlantis was an island with a fertile plain with a mountain range protecting it from the northern wind. The island was ruled by ten kings. It also had elephants living there.

What are the chances of two identical islands.

Cyprus had all of the above.

Could Cyprus be the island of Atlantis?

https://books.google.com.cy/books/about/Atlantis_The_Cypriot_Empire.html?id=K2LP0AEACAAJ&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y

That’s where the Thera theory comes in.

Thank you for mentioning the Perry Rhodan books. They are what initially got me hooked on science fiction during my own “golden age” many decades ago.

Aside from the main series, which has been in continuous publication in Germany since 1961 (issue number 3287 just came out this week), there have been various spin-offs and miniseries, one of which was titled – wait for it – “Atlantis ” – which ran for a total of 24 issues in 2022 and 2023. The first 12 issues were set on the titular island continent in the past, and the second 12 issues featured an Atlantis that had survived its destruction and continued on and prospered in a parallel timeline.

While I don’t read German, the American translations of Perry Rhodan, as published by Ace Books, were very important to me at one time. I believe I read the first hundred of them, which don’t exactly match up to the first hundred in the original because the first few volumes had two each, and they skipped a few at the beginning (then serialized them in the back a few years later).

They appeared on a local drugstore rack reliably, at a time and in a place (somewhat rural) where SFF was hard to come by, and they were as important to me — and I will claim, ultimately of roughly the same overall quality — as the Skylark and Lensman books, which, like the PR books, I believe I would find just about unreadable today.

While it’s certainly still mainly a space adventure series, Perry Rhodan today isn’t the same in terms of style and content as Perry Rhodan from the 1960s, on which those old Ace edition translations were based.

For example, check out the Perry Rhodan NEO reboot, launched in German in 2001 as a new ongoing series separate from the main series (which has been published continuously on a weekly basis since September 1961).

PR NEO is available in English translation in an electronic edition published by J-Novel Club (https://j-novel.club/series/perry-rhodan-neo). Those books can also be obtained in Kindle from Amazon (https://www.amazon.com/Perry-Rhodan-NEO-%2528English-Edition%2529-8-book-series/dp/B0936CHB46).

Hunh. I did not know about the NEO thing. Covers look like manga. I may check one out.

David Gemmel has his Sipistrassi novels which had Atlantis as more of a setting to the normal heroics.

Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, iirc, has Nemo and Arronax visit Atlantis during an underwater harvesting mission…

Hardly central to the plot, but I’ll mention the first section of Triplanetary, the fix-up Lensman prequel by Doc Smith, where we’re treated to a war between Atlantis and the nations of Uighar and Norheim featuring aircars and ICBMs.

Why has no one mentioned Ascension by Kara Dalkey? It has one of the best & most unique underwater worlds ever, set in Atlantis itself. It influenced me to write underwater themed stories. And it’s a quick read too. Also such gorgeous covers.

Jan Siegel’s Fern Capel trilogy (it starts with Prospero’s Children) is one of my favorite Atlantis-inspired stories.

Jane Gaskell’s Some Summer Lands is the sequel/coda of her Atlantean series, the Atlan Saga. Not a very good sequel/coda. But even by the standards of ’60s-’70s Atlantean SFF, the Atlan Saga was particularly strange.

It is also published with its first book split into two volumes, which makes reading the entire series a bigger challenge than usual for an older series.

Lest you think I exaggerate, KW Jeter’s 1979 novel Morlock Night mashes up Atlantis with HG Wells’ The Time Machine and Arthurian legend.

There was also a short series (possibly a trilogy) which mashed up Arthur, the Aeniad, and Atlantis, via the cod-history of Brutus as the founder of Celtic Britain.

Another 1970s title, a humorous fantasy novel by John Jakes titled Mention My Name in Atlantis, satirized Conan and sword & sorcery (an interesting take from someone who, before his American series hit big, was best known for his Clonan character Brak the Barbarian).

Alas, I neglected to mention that KW Jeter’s Arthurian Atlantis time travel mash-up SF novel Morlock Night is also a foundational steampunk text, and that Jane Gaskell’s Atlan Saga is as good as it is weird.

Probably the first Atlantean novel I read was 1973’s sword and sorcery adventure, The Black Star, by the late writer and editor Lin Carter. Like the others I’ve mentioned, it brought the ’70s Strange. Partly this strangeness was a result of incorporating Madame Blavatsky’s polygenetic pseudo-Hindu Lemurian racist nonsense. How ironic that The Black Star was one of Carter’s better works of fiction. A sequel was promised but apparently never published.

It’s been a long time, so I may misremember, but I believe it’s related to Carter’s S&S series about Thongor of Lemuria (speaking of sunken pseudo continents).

Number 1 is my favorite footnote ever. Number 5 is pretty good too.

I really like Jan Siegel’s fantasy series, in which Atlantis is a big part. Not sure on the overall name, but the novels are Prospero’s Children, The Dragon-Charmer and Witch’s Honour (which I’ve not read yet)

Marion Zimmer Bradley has written of Atlantis. The Fall of Atlantis takes place in… Atlantis. Ancestors of Avalon has Atlantis be the starting point before characters flee to Britain.

I’ve recently published a book, Atlantis, Land of Dreams, I reached out to Reactor, but don’t have a major publishing house backing me, so I don’t think the right people heard me. You can find it in any Amazon store. This novel set 11,000 years ago, explores what probably actually happened to Atlantis through the eyes of its main characters. It is intended to be inspirational as well as entertaining and is backed by documentary and physical evidence. Please take a moment to find out more by typing “Atlantis, Land of Dreams by Edale Lane” into your search box.