Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

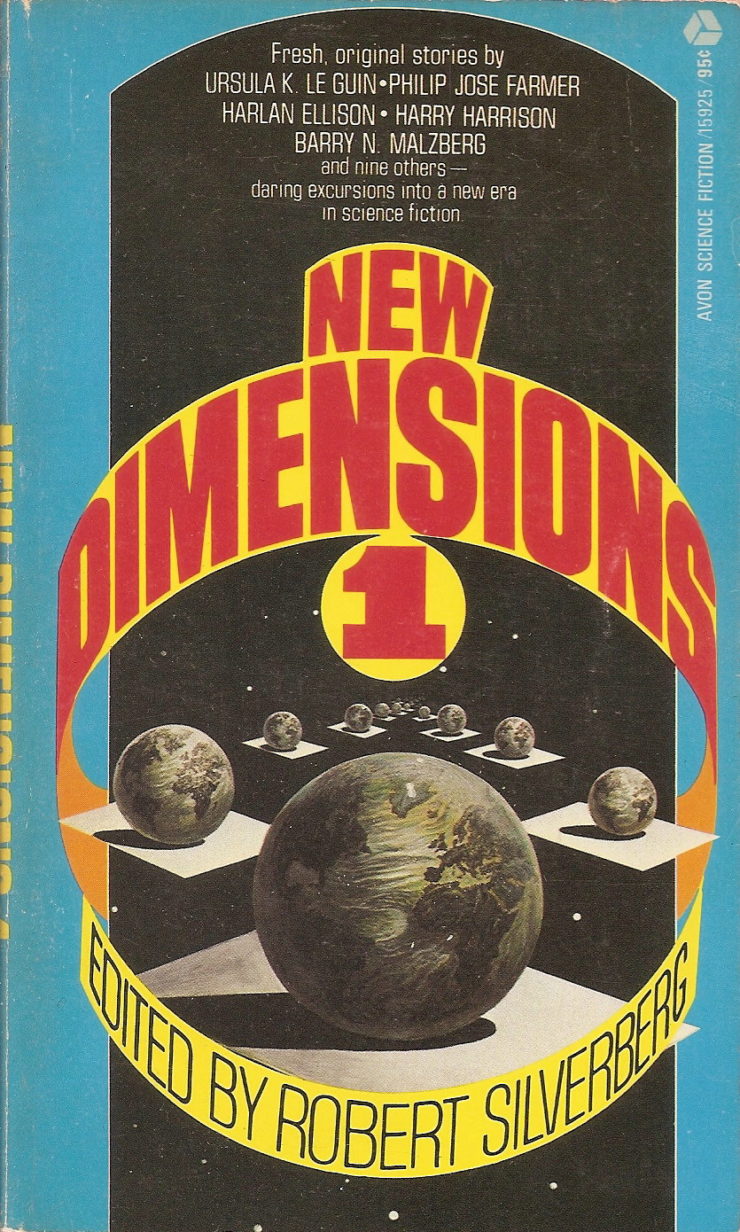

Today we’re looking at Howard Waldrop and Steven Utley’s “Black as the Pit, From Pole to Pole,” first published in Robert Silverberg’s New Dimensions anthology in 1977. You can read it more recently in Lovecraft’s Monsters. Spoilers ahead.

“It was only when he began to make out the outlines of a coast in the sky that he experienced a renewed sense of wonder.”

Summary

The story’s scaffolding is complex, but our Omniscient Narrator kindly lists its components:

In 1818, Mary Shelley published Frankenstein. John Cleves Symmes published a treatise claiming the earth is hollow and holds concentric spheres, accessible at the poles. Edgar Allan Poe was nine. Herman Melville wouldn’t be born for another year, but Mocha Dick (the future Moby) had already established himself as the terror of South Seas whalers.

Braiding these random threads is no other than the Monster Erroneously Known as Frankenstein, more accurately Frankenstein’s Monster or simply “the creature.”

“Black as the Pit” picks up the creature’s story where Shelley let it fall into icy oblivion. Frankenstein’s pursued his murderous creation to the North Pole before dying in the care of an English ship’s captain. The creature grieves over Victor’s corpse. He’s achieved no vengeance, only isolated himself through his crimes. He floats off on an ice floe, expecting death and welcoming it.

But the creature’s too tough, and slips back out of oblivion. Has that fiend Victor made him immortal, too, subject to endless loneliness? Angst is interrupted when a second sun appears, and the polar icescape sinks into a vast bowl down which he slowly slides. Many disorienting perspective shifts later, a “dark landmass” swims above him. An unnatural man, he claims this unnatural land as lord.

It seems Frankenstein’s creature has stumbled into Symme’s hollow earth! His first discovery is a ship crushed in the ice pack. Three iron-hard corpses guard its treasures—the creature outfits himself with warm clothing, food, and weapons. Then he starts walking.

In the first sphere he encounters prehistoric mammals, such as mammoths, then a marshy realm of dinosaurs. Too many predators. The next sphere contains a vast sea, plagued by lightning storms. Not prime real estate. World after world follows. The creature marvels and shudders at what he sees, refuses to admit loneliness. He needs no companions. He has the strength and will to claim any sphere. In a world dominated by primates, one great ape lords it over all tribes. The creature kills it and becomes a legend of awe and fear to the other apes for generations.

The creature presses onward. He passes the center of the earth, and finds a world that hosts men. His first thought is to kill them. His overwhelming impulse, though, is to reach out. He fears that when they see his patchwork ugliness, they’ll hate him. Let them. Ugly as he is, he’s also huge and fierce, and he has firearms.

The creature conquers all, from the forest tribes to the city-states. But in proud Brasandokar, he too is conquered. Megan, blind daughter of the War Leader, catches the creature’s eye by the calmness with which she witnesses the sacking of her city. Her frankness further impresses—she does not love him, but perhaps she could come to love him.

They marry. Echoing the creature’s own curse, Victor’s ghost visits the couple on their wedding night—and repeatedly thereafter, promising the “monster” will lose everything as Victor did.

It’s true—happiness makes him too peaceful for his underlords. Rebels kill him and Megan. The creature revives. Megan doesn’t. In his grief, the creature runs berserk through Brasandokar, leaving it in flames.

He rafts into the next world on a subterranean river. At last he reaches a cavern full of giant white penguins. They chase him into halls peopled by intelligent beings—though not men. Before long he encounters them, with their barrel-shaped bodies, leathery wings, starfish heads. The creature grabs a halberd and looks for a way out. The barrel-beings try frantically to keep him away from one portal. The creature gets it open, only to release a stinking mass of gelatinous horror that sucks down barrel-beings whole!

Everyone runs. The creature makes it out to another icy coastline, having traveled through the earth from pole to pole. A volcano melts ice into a cataract. As ash rains down, Victor’s ghost mocks him: Welcome to the Pit. Hell, demon. You are home.

The creature might have sunk in despair if a canoe hadn’t come along at that moment. There are two white men in it, and a dead black man. The creature steals the canoe. Overhead birds cry Tekeli-li, tekeli-li.

With Victor’s ghost riding along, the creature paddles out to sea. In the blood-red twilight, he sees an ice-island bob. Wait, it’s a huge white whale, stuck with innumerable harpoons and lances, yet hanging in the air like a heavy cloud before slowly sliding back into the ocean.

The creature feels “God had passed through this part of the world and found it good.” “Free!” he yells. Then he sculls north toward the lands of men, while Victor sits frowning in the prow.

What’s Cyclopean: The monster’s “handseled heart” is a deliciously ironic description—to “handsel” is to give a gift for good luck.

The Degenerate Dutch: The connection between Hopi origin myths and hollow earth theory seems a bit shallow, merely pointing out that people have almost universally been convinced that there’s something Under There. On the other hand, a 1977 story gets some credit for noticing that the Spanish conquest wasn’t a good thing.

Mythos Making: The monster doesn’t exactly stop to learn what they are, but just below the Arctic he meets extremely recognizable elder things and shoggothim.

Libronomicon: “Black as the Pit” offers a full shelf of literary references, most notably Frankenstein and John Cleves Symmes Jr.’s miscellaneous writings on the hollow earth.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Rejection, and the death of his wife, drive the monster to homicidal fury. Is that madness, or just anger?

Anne’s Commentary

How better to wave farewell to National Poetry Month than with verse? Here’s some from Henley’s “Invictus”:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

So it’s from there our story takes its title. Nice irony, that Henley’s ringing orator has no doubt about possessing a soul, and an unconquerable one no less. Less certain of his spiritual status is Frankenstein’s creature, whom Waldrop and Utley put through misadventures even more trying than those Shelley penned.

I bet they had a great time, too, maybe challenging each other to come up with one more ingredient to toss into their fictive stew. The meat, appropriately enough, is supplied by Frankenstein. Your stock vegetables are the nonfictional elements: Symmes’s “hollow earth” theories; Jeremiah Reynolds’s Antarctic expedition; the 1844 Franklin expedition to the North Pole; Native American legends of the Under-Earth People. The potatoes and carrots, the herbs and spices, are fictional works that contribute either structural bulk or allusive flavor to the narrative: Poe’s Arthur Gordon Pym, Melville’s Moby Dick, Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, Burrough’s Pellucidar books.

While the allusions to Verne and Burroughs come late (to Prof. Otto Lidenbrook, who descends into an Icelandic volcano; and to Abner Perry, tinkering at curious inventions in the family attic), their visions of inner spheres occupied by prehistoric creatures, ape tribes, and restlessly feuding states transfer readily to Waldrop and Utley’s hollow earth. Pym gets shortest shrift, only showing up long enough to supply the creature with an escape canoe near story’s end. Moby Dick gets little “page time,” but his is a star turn as bringer-of-epiphany.

Mountains of Madness gets some space, but I found this episode the most disappointing. The best part was the creature’s approach along the subterranean river of phosphorescent salamanders. The albino penguins and Elder Things? They struck me less as awe-inspiring aliens than Keystone Kops dashing haplessly around, unable to keep the intruder from squishing their eggs and, oops, opening the wrong security hatch. Who let the shogs out, squelch-squelch-squelch?

The longest section is set in the sphere inhabited by men, and by Megan of Brasandokar. Is there some particular SFF tragico-romance this echoes? “Brasandokar” seems an original place name, at any rate.

On the Other-theme front, “Black as the Pit” starts with a protagonist as otherly as a character can get. Victor’s creation is unique in the most uncomfortable sense, a One with no Family, human or Divine. A One with no Tribe, not even in broadest state-of-existence terms. Having died, can he belong among the living? Having been revivified, can he belong among the dead? Having been cobbled together from many, has he an integral self? Having once given up the ghost, has he a soul?

Abandoned between death and life, where in all the burning hells does he belong?

Funny the creature should mention burning hells—not that all the ones Waldrop and Utley have in mind are literally on fire, but still, they’re stocked with a nice assortment of other Others to provide Victor’s monster with monsters of his own.

The first sphere features Nature’s own Others—predators intent on eating the creature, herbivores intent on keeping the creature from eating them. Prehistoric mammals. More prehistoric reptiles. Mammoths. Velociraptors. Giant primordial fleas and ticks. Nature can sure be a mother.

In the sphere of the apes, he encounters an Other who embraces standing apart. The giant ape exploits his strength to dominate but seems to belong to no tribe. Whether this isolation is an acceptable trade-off to the ape, we don’t know. It does get him killed when the creature stumbles across the ape’s solitary nest.

The sphere of men is lousy with Others, with or without reference to the creature. Each forest tribe Others the next forest tribe downriver, which encourages forays for body part collection. The forest tribes and city states Other each other, and the city states Other the other city states, and it takes the ultimate Other that is Victor’s creature to unite these yapping dogs of war under his gun-toting hand.

Unfortunately for the creature’s tenure as warlord, love leaves him too at peace to let his underlings squabble profitably. Fortunately for his emotional education, he finds Megan to be mutually Oneish—proven by ghost-Victor’s determination to undermine his creature’s happiness, for ghost-Victor (like living Victor) can only see his creation as Other, Outsider, a demon.

We get the alien Other in Lovecraft’s Elder Things and shoggoths. But again, for me they don’t suit this story, seeming tonally too modern in comparison to the 19th-century-flavored literary shout-outs. Too cosmic, too, where all else has its roots (real or mythical) firmly in Earth soil.

Melville raises Moby Dick to truly ecstatic Otherliness in his chapter on the Whiteness of the Whale. The creature, seeing Moby in so magnificently complimentary a setting as the red-lit Antarctic sea, is himself struck ecstatic. I think what drives his exhilaration is not Other-worship but Oneish-recognition, identification. Here is the monster of the whalers, scarred hump to tail, killed a hundred times over by the harpoons and lances he still bears, but alive and defiantly free.

“Free!” as Victor’s creature can shout, because the epiphany that evades frowning Victor is his.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“Black as the Pit from Pole to Pole” deserves a whole post’s worth of footnotes. First there’s Frankenstein’s monster—Shelly’s monster, really—and the seesawing tension, here and in the original, between yearning to be part of the human world and violent fury when it rejects him. Then there’s Symmes’s quixotic variant on hollow earth theory, and the places where Waldrop and Utley depart from his real history (no actual expeditions mounted, and the authorship of Symzonia remains contentious). Edgar Allen Poe’s arctic, and Lovecraft’s. The kiva holes, where gods emerged to begin creation. “I am the master of my fate; I am the captain of my soul.”

And all the stories building on these stories, in conversation with them, concentric rings uncountable and ever-expanding. “We are all parodies here,” says Frankenstein’s/Shelley’s man/monster.

I love tracing literary conversations across the decades and centuries. I also love Shelley’s monster, and am a complete sucker for any story that gets him right and doesn’t think the original was about the hubris of men playing god. (There are a lot of stories about that thing. There are fewer perfect tragedies in which the protag’s fatal flaw is that he’s a bad mom.) So I loved… about the first two thirds of the story.

For me, it starts to go off the rails with Lady Megan’s death. Shelley was all about the love of pure and innocent women as a source of angst, and Megan’s death does in fact provide symmetry with that of Frankenstein’s wife—and yet, none of that makes me more delighted with fridging. In a story about the grand literary conversation, I kept waiting for some statement beyond “hey look, this is a conversation.” In the original, too, hatred and rejection drove Frankenstein’s creation to violence—and “Black as the Pit” falls comfortably into the same old round of almost-acceptance, rejection, and violence—and this week of all weeks, this year of all years, I wanted some commentary on that pattern rather than just watching it happen again. That’s not entirely the fault of a story that came out in 1977, and yet nor is it my fault for being a reader in 2018. But lest we take “of its time” as too easy an answer, “My Boat” came out in ’76.

We authors do know, when we send our bottled messages out into the grand conversation, that they’ll be read in the future.

So I was already frustrated by the time our Deliberately Unnamed Narrator finally made it from pole to pole. And when he got there, I wasn’t sure why. Yes, Lovecraft was in conversation with Poe’s Pym, and with all the hollow earth stories, and with Shelley’s assertions about what counts as a man—and he should have been in conversation with her assertions about the obligations of creator toward creation. This story could have said something about the parallel between the Monster and the shoggothim, but no, they were all just scary things trying to stab or swallow each other. It seems like a hell of a missed opportunity.

And then, just as I’m getting completely irritated, Moby Dick breaches the waves and gets properly recognized as the deity he represents in his original story—another one that I’m always delighted when someone gets right.

At which point, as I sit here trying to figure out how I feel about the whole thing, another part of the conversation suddenly breaches my consciousness. Waldrop and Utley’s/Frankenstein’s/Shelley’s monster/man thinks of the subterrestrial worlds as hells—and passes through them to see god. Symmes’s hollow earth had five concentric rings; this version has more. More like… 9? Like Dante’s hell, where one might encounter gluttonous dinosaurs and lust-driven apes, and humans with all their violence, and shoggothim with what Lovecraft at least considered treachery?

Final judgment: frustrating as an entry in the Grand Conversation, but potato chips for Where’s-Waldo-style reference spotting. One can do far worse.

Next week, Edgar Allen Poe’s “William Wilson” offers a classic other—all too much like oneself.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.