From time to time, SFF authors have been known to branch out into non-fiction. Asimov, whose post-Sputnik efforts included works in all but one of the Dewey Decimal classifications, is perhaps the most obvious example1, but contemporaries like Anderson, Le Guin, Russ, and Clarke have also strayed into the realm of non-fiction.

An author considering this move might wonder which subjects they should choose. Of course, a correct answer is “those fields in which one is either an expert or prepared to research in depth.”2 However, a more marketing-based answer might be “science fiction (and fantasy) adjacent non-fiction fields that seem to be evergreen, whose readers are always keen for new books, regardless of any lack of progress in those fields.”

Might I suggest some subjects that might find an audience?

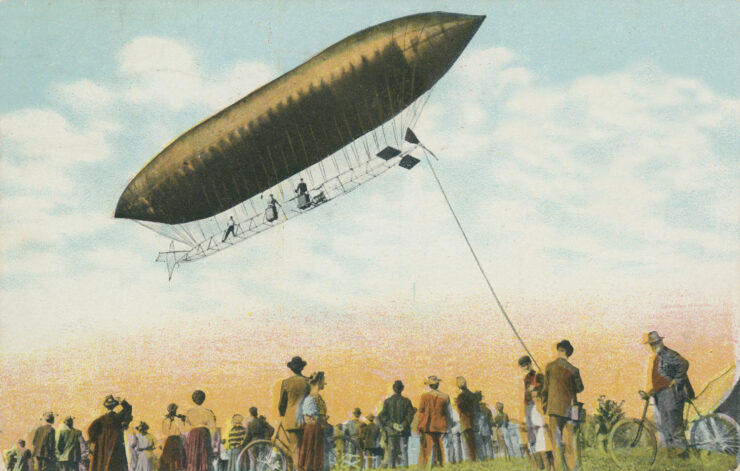

The Coming Age of Airships

About once a generation, people rediscover the positive qualities of airships. They are majestic and (compared to heavier-than-air vehicles) comparatively quiet and fuel-efficient. The fuel efficiency appeals for several reasons. When fossil fuels are expensive, less fuel equals savings. Also, less fuel used means airships emit less pollution, which is always a plus.

Authors might wonder why, if airships offer so many advantages, we are not now living in a golden age of lighter-than air vehicles. There are a number of reasons:

- airships were labor-intensive to operate, requiring larger ground crews than equivalent heavier-than-air vehicles;

- there was a perception that airships are prone to catastrophe;

- passengers were willing to pay a premium to arrive faster.

Automation might address the first issue. The second is less tractable. Improved design can reduce risks3, but the fact is that being lighter than air means having a comparatively low mass to surface area. LTA craft are by their nature kites, more vulnerable than airplanes to the vagaries of weather.

The third issue is really a matter of marketing. How should an author’s unwritten book address that? I leave it to marketing specialists to address that issue, although philosophizing about how the journey is more important than the destination seems the logical first step.

Note that if the writer is successful, the age of airships will finally arrive. That will put an end to books urging the adoption of airships. Writer beware.

Alarmist Books About Population

At any given moment population will be static, rising, or shrinking. Also, specific demographics will be a steady fraction of the overall population, an increasing fraction, or a decreasing fraction. Viewed through the correct lens, these are always causes for alarm. Net growth threatens Malthusian collapse and/or ecological doom. Net reduction threatens economic collapse if the employed fraction is too small to support retirees. Steady state… actually, it’s not clear why that’s bad, but I am sure it is.

The obvious pitfall in population alarmism is that almost every reason for concern about population boils down to some people being more valuable than others4. It can be challenging to write about population management without a racist, or classist, or some kind of “ist” subtext (or in some cases, overt text). The good news is that this does not seem to have inhibited previous population alarmists. Some appear to have found the prospect positively inspirational… The field is still wide open!

Space Colonization

Finally, we get to my favorite topic. I own many, many books about space colonization. Humans having established themselves across the entirety of Earth (even such inhospitable regions as Milton, Ontario), it seems only logical that humans should spread to the planets, asteroids, and moons of our solar system…and perhaps beyond. The subject provides ample opportunity for inspirational illustrations and appeals to human destiny.

As one might guess from the current striking lack of space colonies, transporting people to space and keeping them alive once they are there is at present difficult and expensive. In many cases it is beyond our current abilities. There is also no compelling reason (at present) to conduct the necessary research and development, and no reason to invest in this field.

This could be a plus for an author. The field has been static for so long that it will be easy to crib points from earlier books now out of print. Just be sure to erase the fingerprints on the plagiarism inspiration.

I note that future historians will be interested in whatever arguments are advanced for space colonization. The arguments tend to be a valuable record of social anxieties at the time of writing5.

Pseudoscience

Consensus science has a bad habit of demanding study, being subject to correction in light of later evidence, and worst of all, telling us that which we do not wish to hear. Pseudoscience, on the other hand, provides shortcuts, the comfort of certainty—even in the face of contradictory evidence—and the benefits of confirmation bias.

There are vast fortunes to be made inventing and promoting ludicrous pseudosciences6. However, a vocal minority believe that bilking the willfully gullible is in some obscure way unethical, even when the target chooses to be a dupe. Happily, there is a more ethical, equally evergreen option: non-fiction texts detailing and decrying various fads and fallacies in the name of science7. The subject matter is abundant and the potential readership of skeptics nearly as abundant. Best of all, your book will have absolutely no effect on the spread of nonsense, guaranteeing a never-ending market for increasingly despairing texts!

Those are my top four picks for non-fiction subjects whose lengthy track records suggest that they will not soon be out of fashion. Perhaps I’ve missed some of your favorites. Feel free to make a case for them in the comments below.

- Asimov is the obvious example for readers of a certain age. Younger readers might not find it obvious. ↩︎

- Asking ChatGPT is not researching in depth. ↩︎

- Item one for airship safety might be replacing hydrogen with helium, but not only is helium denser than hydrogen, terrestrial supplies are limited and growing more limited every day. Another approach would be to convince major airplane manufacturers to make their products less safe. This turns out to be much easier than I would have expected. ↩︎

- A snarky person might assert that the ecological alarmist prioritizes non-humans over humans. However, my contractual obligation to appear marginally reasonable at least once per essay, even if only in a footnote, requires me to point out that if humans destroy the biosphere on which we are entirely dependent, we will soon follow. ↩︎

- For example, Cole and Cox writing in the 1960s suggested that space colonies would be a solution to nuclear proliferation. O’Neill, writing in the 1970s, thought space colonies could address resource limitations. The key is to find some way in which space colonies are the solution to whatever the big problem of the day happens to be. ↩︎

- It’s said that some con artists deliberately make their cons painfully obvious to weed out all but the most gullible of patsies. ↩︎

- Fads and fallacies in the name of science would be a catchy title for some gardener in the fields of human folly. ↩︎