Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

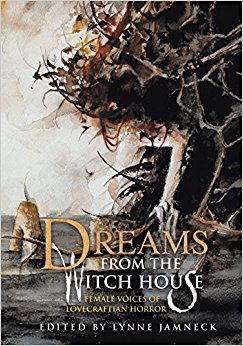

This week, we’re reading Amanda Downum’s “Spore,” first published in Lynn Jamnek’s 2015 Dreams From the Witch House anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“What is this, like Humans of New York?”

Summary

Beth Jernigan’s a widow, sort of. Her partner, Dr. Dora Munoz, has vanished on another of her spur-of-the-moment trips in search of weird plants or fungi that might cure anything from cancer to the common cold. Nothing new, only this time Dora’s stayed vanished. She has sent a couple messages from nowhere. The first, accompanied by enough money to pay off their lease, said Dora was “going off the grid.” The second invites Beth to take on a project.

As the project involves interviewing people, Beth’s perfect for the job. Dora used to joke that Beth chose to become an anthropologist so she could learn how to talk to humans. They both knew it wasn’t really a joke. But Beth’s sick of job-hunting, and maybe she’ll find Dora again, dangerous, passionate, manic, and brilliant.

Beth asks her subjects about their experiences with a certain fungal hallucinogen. Religious Studies grad student Aaron tells her the mushrooms gave him weird spots, and dreams. A doctor prescribed antifungal drugs, but before he could take them, Dora introduced him to some of the others. Yeah, he was scared. But see, he’s not alone. He feels the others, like white noise in the back of his head, however crazy that sounds. Which, to incredulous Beth, is pretty crazy.

Her next subject is Anne. She met a guy at a party who lectured about human consciousness and interspecies communications, then gave Anne mushrooms that would “give her a new perspective.” A three-hour trip of weird intensity does just that. The mushroom guy she’s only seen again in dreams. Whatever this thing is, he’s “further along” than Anne.

Beth asks if it’s an alien parasite, a psychic fungus? Anne, picking up on her skepticism, wonders if she’s wasting her time. Beth apologizes, but just wishes she understood. Has Anne considered taking anything? Antifungals?

Anne laughs bitterly. She’s considered taking a lot of things, including a dive off a roof. Her life wasn’t great before, but at least it was hers. She’ll never get that back. But— the dreams feel so good…

Another day, another city. In a dingy bar called the Angel’s Share, Beth meets Minette. After her first mastectomy. Minette was told she had another tumor and “ran out of rope.” She sought alternative healers and found a woman who gave her mushrooms that would “help the pain.” They’ve done much more than that. Beth wants to believe her, but can’t. Minette slides her a plastic bag full of dry gray-brown tendrils—from Dora, who wanted to see her, but had to leave too early.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Minette serves Beth bourbon and goes on: Dora says it doesn’t have to be permanent. You could get treatment after one dose. But one will be enough for the dreams. As for Minette, after surgery she felt like a freak. Now she feels beautiful again. She takes off her T-shirt. From her mastectomy scar grow whorls of fungus like rose petals, white at the center, shading at the edges to yellow and teal. When Beth sits dumbstruck, Minette seems disappointed. She puts on the shirt, goes off to open the bar.

Later Beth stands naked and wavering before the mirror in her hotel room. Should she quit and go home? That’s no inviting prospect: work and debt and fleeting relationships. Or else the bag. Maybe it’ll give her a few hours of pretty lights. Maybe it’ll turn her into a fungus zombie. She picks out the biggest stem, chews, swallows, lies down. Her body slowly numbs. Her senses sharpen. She senses “the gravity of another presence.” Of Dora.

Dora explains that playing host to the fungus can shorten human lifespans, but in return it takes you into its web—your memories, identity, maybe even soul, all incorporated into a greater whole. “They’ve spored a hundred worlds,” she says, “seen and preserved things humans can only dream of. They’re historians. Archivists. I’ll live forever with the colony. Learn forever. Long after every human civilization has fallen to dust.” In Dora’s voice, Beth hears the passion she’s always envied. How many cultures are archived willingly, though?

Many. Some worship the colony. And if the practical rewards aren’t enough, there are the chemical ones, the euphoria of the dreams.

But why did Dora bring Beth to this? To spread the infection, of course. And because Dora’s missed her. Her own transition into the colony was so swift, she couldn’t see Beth in the flesh again as she wished. Not that she’d do things differently.

The next night, Beth returns to the Angel’s Share. When it closes, Minette says she looks rough and leads her upstairs. They’re drawn together in a kiss. They make love. Beth tastes the whorls of fungus on Minette’s chest, earth and cinnamon that open under her tongue.

She dreams of Dora. “Growth like creamy lace sprouts from her skin, envelops her like a bridal gown… She smiles at me, and something stirs in response beneath my skin. For once I’m not alone.”

Two weeks later Minette’s gone. She leaves the keys to the Angels’ Share. Another week, and Beth’s polishing the bartop when Aaron, her Religious Studies subject, walks in. She smiles at his surprised recognition but skips the snark. Better to be nice, since they’ll be knowing each other a long time.

What’s Cyclopean: Beth’s more poetic in her descriptions of the fungus than her lover: fruiting bodies curl together like rose petals, growing like lace through skin.

The Degenerate Dutch: No prejudices here—we are all one in the colony. And after all, if you’re going to know people for that long, you want to be nice to them.

Mythos Making: There’s a fungus among us.

Libronomicon: The spores describes themselves as archivists, but written material doesn’t appear to be their preferred form.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Beth doesn’t want to get therapy for her relationship issues; that would imply there’s something wrong with her.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We practically have a catalog by now, don’t we? A sparkling array of possessing aliens, fungi, and alien fungi, new and on sale just in time for the holidays. Have trouble choosing? Don’t worry, one will be chosen for you.

This is assuming, of course, that we knit all the Things That Want Space In Your Brain together into one mythos full of terrifying opportunities for transcendence. Not only Lovecraft’s original Yith and mortality-defying sorcerers, but the brain-eating, body-controlling fungi from “Leng,” the universe-spanning amorphous blob from “The Things,” whatever the hell is going on in “The Woman In the Hill,” even the beer from the corner store… my point is that the elder gods have an inordinate fondness for parasitic wasps* and this type of survival strategy is not limited to Earth. The universe is full of things that think human brains make terrific nest material.

On the possession desirability scale, the Yith are clearly at the top. They only borrow your brain for a few years, after all. The rewards are immense, and the costs are at least comprehensible. At the rock bottom end of the scale are mushrooms that replace your entire body and provide nothing in return—and it’s always mushrooms, you’re never getting consumed and replaced by tomatoes or kittens or something. Amanda Downum’s “Spore” falls squarely in the middle. The fungus becomes you, sure—but you also become the fungus. That’s fair, right? Oh, and you’ll never be alone again.

That last bit is extremely tempting, to the right sort of person. And for the introverts who appreciate having dreams to themselves, there’s a complementary promise: you’ll never be forgotten. The spore colony is an Archive, of sorts, for all the lives that have passed through it (in the digestive sense). But for Beth, loneliness is a bigger motivator than any desire for legacy. Loneliness, that she doesn’t want to admit is even a real thing—or if it is, that it’s anything less than universal—but that she’ll do anything to sate. (Anything except go to therapy. My personal opinion: if you don’t want to go to therapy because it would mean there’s something wrong with you, but you are willing to solve the problem by feeding yourself to a mushroom, you could probably use some therapy. Also, if anyone was looking for a case study around the impact of mental health care stigma, here you go.)

Mind control and possession inherently have the attraction/repulsion nature—or at least, people who aren’t occasionally intrigued by the thought of sharing head space probably read a different genre. I’m not particularly over these tropes myself. “Spore” is a wonderful example, balancing the attraction and repulsion perfectly. Beth’s research project runs through all the reasons why such attraction rears its head: scientific curiosity, infatuation, loneliness, existential desperation. As a bonus, the story’s full of well-realized women, something I was yearning for after our last two selections.

Jernigan, ultimately, can’t trust any connection that isn’t immediate, tangible, and irreversible. The fuzziness of human emotion, the inherent untrustworthiness of neurotransmitter levels—as far as she’s concerned, these are no basis for any kind of stable relationship. Once you get to that point… I don’t know. Maybe alien mind control mushrooms are your best bet.

Me, I’ll stick with dopamine.

*I apologize for sharing the knowledge in this article, which probably belongs in the Miskatonic library’s restricted section. If you’re phobic of insects, maybe don’t click through.

Anne’s Commentary

According to her author biography, Amanda Downum may or may not be a barrel of crabs piloting a clever human disguise. Reading this over my shoulder, intrepid reporter on all things eldritch, Carl Kolchak, choked on his coffee. When he had recovered and cleaned up the spewed java and bourbon, he said, “Of course! Crabs, right? And fungus from space—the fungal crabs from Yuggoth!”

“The Mi-Go?” I queried, aghast. “You—you don’t think Downum could be—”

But before I could stammer out the rest, Carl had grabbed hat, recorder and camera and was out the door. So, Ms. Downum, if you get a visitor shortly, and you are a barrel of crabs, please don’t shred him with your pincers. We kind of like him around here. Or, wait, if you are a Mi-Go, don’t can his brain. Seriously. It could crash your whole transplutonian network.

Caveats issued. Let’s get back to the mushrooms, one of Howard’s favorite embodiments of the decaying and weird. The fungal, or at least pseudofungal, is the very substance of one of his great interstellar races, the Mi-Go of Yuggoth. Downum’s fungal collective has no spectacular corporeal phase, winged and clawed like Howard’s; it has, I think, no corporeal individuals. Yet Dora, incorporated into the collective, claims to have retained her self: memory, identity, soul. It’s the same claim Akeley (or false Akeley) makes in “Whisperer in Darkness”: Sure his mind is in a can, but it’s still his mind, and now it can travel anywhere, into fabulous regions beyond human ken, and it can live forever. Immortality without sacrificing the self, just the cumbersome body!

Akeley makes the further reassuring claim that the Mi-Go can keep one’s brainless body alive while the brain sojourns elsewhere, then reunite the two, no problem. Downum makes no such offer. It’s unclear what happens to a spore-infected body when its mind transitions into the collective, but there’s obviously no coming back from the switch. Here “Spore” resembles another story we’ve examined, about which more below. Also, Downum’s description of the fungal collective’s grand mission makes it sound rather more Yithish than Mi-Gooey: They are historians, archivists, preservers of cultures. An interesting “amalgamation” of the two Lovecraftian races, in my mind.

So, that other supremely fungal story! It’s Marc Laidlaw’s “Leng.” Dream-Dora tells Beth that her miracle fungus is not “O. unilateralis.” She means it’s not Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, an entomopathogenic fungus that attacks certain rainforest ants, forcing them to desert their canopy colonies and isolate themselves until the fungus sends up a fruiting body from their heads, which erupts to spread spores. Laidlaw’s deadly fungus is called Cordyceps lengensis, which parasitizes a caterpillar called the Death or Transcendance Worm. But C. lengensis is also homopathogenic—it will happily parasitize humans, eventually turning them into gray sacks of spores, crowned with a single grasslike fruiting stalk. Laidlaw’s narrator learns that the entire plateau of Leng is but a thin earthen skin for the vast underground body of C. lengensis. The priests of Leng believe that inoculation with the spore will lead to a richer, deeper way of knowing. But narrator glimpses, too late, that the “squirming ocean” beneath Leng wishes only to “spread, infect and feed.”

Downum’s more optimistic, despite or maybe because she’s vaguer about the life cycle details of her homopathogenic fungus. Or should we call it homosymbiotic? And even then, as Dora corrects Beth, symbiosis can be parasitic (harmful to the host) or commensal (beneficial to one organism, neutral to the other) or mutualistic (beneficial to both). And Dora’s fungus can be any or all of the three. Much depends, apparently, on the host. What the host wants and needs. What the host is capable of.

Dora is capable of a great deal. She transitioned into the fungal collective quickly, just as she hurled herself into all her brilliant schemes and adventures. I call no coincidence that Downum named her Dr. Munoz, a nod to that other seeker of immortality through boundary-breaking medicine for whom things didn’t work out so well—Dr. Munoz of the chilly apartment in “Cool Air.” Dora wants knowledge, and can give it in return. She’s a natural for the collective.

She wants to give Beth the opportunity to join, but what can Beth gain? What did the anthropologist not yet learn? How to speak to humans. How to connect. When she takes a second communion of the fungus from Minette’s scar-whorls, she’s accepted. She’s joined. She can dream of herself as a rosebud-cradled fetus awaiting birth, with Dora beside her, growing a lacy bridal gown from her own skin. And now, for the first time, Beth is not alone.

So, assimilation into massive (even cosmic) fungal collective/society: Iffy proposition or good life choice? Among Howard and Marc and Amanda, we’re all over the board on this vital question. Maybe Carl will check back in soon…

Patterns within patterns… and the horror found therein. Join us next week for China Mieville’s “Details,” which you can find in the New Cthulhu anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.