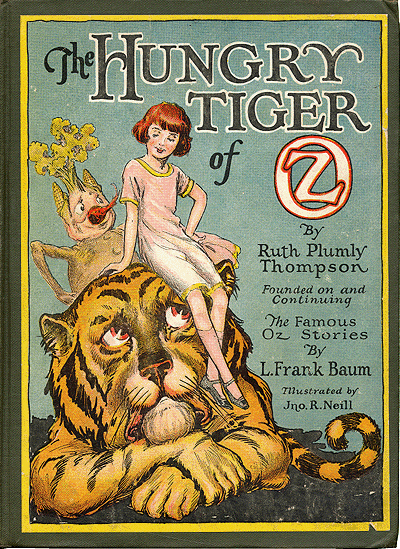

The country of Rash has a problem. No, not that it’s people are quick tempered and constantly breaking out in spots, but an overlarge prison population. (Which is what happens when you usurp a throne and people keep revolting against you. Which would be Rash’s related problem.) The Hungry Tiger of Oz also has a problem. Even the abundance of Oz is not enough to feed him, let alone satisfy his craving for little fat babies. Baum had treated this craving with a bit of a wink. Thompson, however, takes this as a serious desire and need.

The rulers of Rash have a solution to both problems: hire the Hungry Tiger as an executioner, and let him gobble up all of the prisoners. Hey, it saves on their maintenance expenses, and it allows the Hungry Tiger to finally assuage that unstoppable appetite.

Incidentally, the Scribe of Rash, an enthusiastic supporter of the Eat Our Political Opponents plan, has the most useful hand ever—one finger is a pencil, another a pen, a third an eraser, a fourth sealing wax (adding that necessary touch of elegance to any execution document) and the last an actual candle. The thought of never needing a flashlight to read under the covers and always being able to set enemies on fire upon demand has a certain appeal. Not that the Scribe appears to be making use of any of these possibilities.

You wouldn’t think this focus on the consumption of criminals in a country that should be concerned about skin care would be the sort of thing to start off a frequently bitter look at gender roles. But Oz has a gift for offering the unexpected.

The tales of the country of Rash and the Hungry Tiger form only part of the intertwined plots. The next part focuses on Betsy Bobbin, introduced by Baum in Tik-tok of Oz, but who had taken only a minor role in later books. Thompson, perhaps responding to children’s letters, or perhaps satisfying her own curiosity, gives Betsy a central role here. Surprisingly, even in this central role, Betsy still retains a rather passive, colorless personality. She begins by trading an emerald ring for some strawberries, in a scene that not only demonstrates her lack of understanding of comparative costs and value, but also demonstrates that the concept of payment has not quite left Oz, or at least its American visitors—even if they have no idea how much they should pay for things. Admittedly, strawberries might be rare in Oz (although no other food seems to be) but no matter what might be going on with the strawberry crop in Oz, the payment seems a trifle excessive. (In another one of those revealing statements, Betsy explains that she has dozens more emerald rings, which might help explain why Emerald City residents tend to forget money when they head out on fruit shopping expeditions.)

This bartering for strawberries introduces her to Carter Green the Vegetable Man, a man made out of, natch, vegetables, who has to constantly keep moving to keep from getting rooted in the soil. A winding road (which really winds) and some sandals soon bring them to the Hungry Tiger and the country of Rash, where the Eat Our Political Opponents plan is running into a few snags. (It turns out that eating political opponents can cause a few pangs of conscience. Who knew?) It doesn’t take Betsy, the Hungry Tiger, Carter Green and a few of those opponents too long to decide to flee the country—however temporarily—for a little tour of some of the countries outside Oz.

And some of the sexism outside Oz, as well.

In the previous book, Thompson had introduced Catty Corners, a kingdom of talking cats, which did not approve of boys. Despite this, at Mombi’s insistence, one boy had been brought into the town. In this book, Thompson takes the opposite task, introducing one of her most troubling creations: Down Town.

Down Town is ruled by a weak, nervous and cowardly Dad and his queen, Fi Nance, a deeply unpleasant woman who started, she tells us, as a cash girl, and is now literally made of money. (This does not add to her charms.) But even though she is made of money, and is one of the city’s rulers, she is not able to enter Down Town:

“Down Town belongs to the Daddies,” said the sign severely. “No aunts, mothers, or sisters allowed.”

Indeed, as the travelers discover, Down Town has no women, only men busily engaged in creating money. (Betsy does not think that job looks too difficult. Betsy, remember, thought that pints of strawberries and small emerald rings are about equal in value.) Fi Nance shrieks at the travelers for arriving without money (see, another reason why Betsy shouldn’t have been so quick to trade that emerald ring) and orders them to find jobs, adding that it’s easy to make money in Down Town. Finding a job shouldn’t be difficult either, since Down Town also supports a living Indus-Tree, where jobs can literally be plucked from branches.

Most of the men have no problems plucking jobs from the Indus-Tree (the Hungry Tiger, focused on food, doesn’t bother). Indeed, two male characters, tempted by money, decide to stay in Down Town, with the added benefit of whittling the main traveling party cast down to manageable size.

Betsy, however, looks at the tree, which offers plenty of jobs open to women in 1920s America—but chooses nothing. Perhaps Betsy is too young to choose a job, but the equally young Prince Reddy has no difficulty choosing a sword and later stepping into a leadership role. Or perhaps it goes back to her general blankness as a character; we hear only that she is shy (although she has no difficulty speaking to kings), loves onions, and is flattered when Ozma asks for her assistance. Betsy is otherwise a nonentity—certainly likeable, but less real than the confident Dorothy or the thoughtful Trot. Or it reflects Betsy’s realization that the capitalist world of Down Town has no place for her.

In any case, it matches her generally passive role in the rest of the book. She may feature as a main character, but just as in Tik-tok of Oz, she takes little action, merely following the group along. After Down Town, she continues to stand by as Carter Green finds one of the rubies, the Hungry Tiger finds food, and Prince Reddy finds the Hungry Tiger, rescues him from giants, and reconquers his country. Betsy…provides introductions to various characters they meet on the way. (I was reminded of a less cool Lieutenant Uhura.)

Nor is Betsy the only girl to take a passive role in this book. Ozma finds herself kidnapped yet again, this time, by a giant Air Man, Atmos Fere, who drags Ozma to the upper skies. (seriously, someone needs to get this girl some self-defense lessons, and fast, or failing that, some kidnapping insurance. I cannot think of a single other character in any fantasy series who is kidnapped so often.) She does manage to puncture him, nearly killing the both of them and completely destroying some very valuable wheat fields that somebody undoubtedly needed for food, thanks, Ozma, but after that, she, too, returns to an entirely passive role, usually forgetting her magical powers and powders and finding herself literally buffeted by storms and dogs, unable even to rescue herself, despite her powerful fairy magic. When she rejoins the rest of the characters, she is unable to help them, or return herself, Betsy and the Tiger to Oz. The depiction contrasts strikingly from the Ozma with the power to undo a Yookoohoo’s magic, or summon and dismiss people from the Emerald City at will. That Ozma suffered failures of judgment; this Ozma has worse problems.

(Tellingly, when they eventually do return to the Emerald City, no one has been looking for them. Of course, the Ozites do have a spare king on hand now, but given their unenthusiastic response to him, you really have to wonder if the city isn’t secretly hoping, or planning, for the Wizard or the Scarecrow to take over again.)

Given Thompson’s status as a single working woman who had successfully entered, and then left, the male-dominated world of journalism, and followed that up by taking over the writing for a series created by a man, earning enough in both professions to support herself and other family members, Down Town’s negative picture of the role of women in capitalism is understandable and forgiveable. But coupling this picture with the passive images of Betsy and Ozma creates a rather bitter feel, indeed—for if Betsy had been consistently passive in earlier books, Ozma, whatever her myriad other faults, had not.

And yet, many of these negative images—Down Town, a Betsy standing by as others rescue the Hungry Tiger, a helpless Ozma floating in the air and shivering in the rain—all occur outside of Oz, creating a more complex picture than what might be initially seen. Thompson clearly recognized that outside of Oz, not all was well. But she could imagine something else in fairyland, and indeed, would later depict Dorothy, Betsy and Trot* vehemently protesting the suggestion that they remain in traditional, medieval feminine roles, showcasing, yet again, how very different things could be in the land of Oz.

*You didn’t really think that Ozma would be joining this protest, did you? I didn’t think so.

Mari Ness isn’t sure that she’d ever be up to eating her political enemies, or ordering others to eat them. She lives in central Florida.