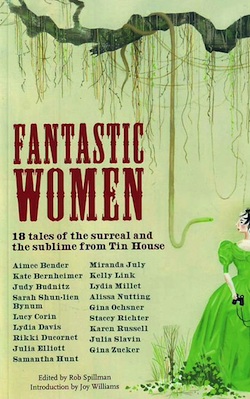

Since the publication of Ellison’s Dangerous Visions back in 1967, anthologies containing speculative fiction have been slipping into our world from various other dimensions. In recent years, anthologies slanted with a slightly speculative angle are materializing more and more. Science fiction mainstays like John Kessel and James Patrick Kelly have recently given us the excellent The Secret History of Science Fiction, as well as the more recent The Secret History of Fantasy. Like Dangerous Visions, the key to a good SFF anthology is to have a specific enough thesis for why the fiction belongs together, but not too limiting as to make the anthology one-note. A recent release from literary magazine Tin House accomplishes just this. The anthology Fantastic Women is exactly what it claims to be: fantastic!

In her introduction to the anthology, Joy Williams talks about her love of the word “peculiar” and how in certain literary circles it seems to have adopted a pejorative connotation. Williams is interested in correcting this, basically asserting that fiction that embraces the peculiar is cool. If one needed convincing that peculiar is cool, then the stories contained in Fantastic Women could be seen as pieces of evidence. However for a reader like me, much of this book simply felt like an early Christmas present.

Edited by Rob Spillman of Tin House, the book is called Fantastic Women because all the authors are female. Is this a political thing? A feminist thing? I’m not really sure, though I’d say it’s neither here nor there in terms of being able to really like this book. Could Tin House and Spillman just put an anthology of “surreal and sublime” tales they’ve published? Sure, and it would also probably be good. But it would also probably be twice and as long OR it would exclude lesser-known authors. When you’ve pieces by Lydia Davis right next to a story by Kelly Link, I for one was kind of glad to not see stories from Rick Moody or Etgar Keret, despite the fact that I love those guys. By having the anthology be only women, it sort of made room for some people I’d not heard of (like Rikki Ducornet and Julia Slavin!), and I think I my life is all the better for it.

Though I like to walk a fine line in Genre in the Mainstream by not really claiming the work discussed for the science fiction camp, some of these stories could have maybe found themselves in the pages of Asimov’s, Weird Tales, or even Tor.com! The Karen Russell entry, “The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach” is probably a good example. In this one, a teenage boy named Nal is confronted with the bizarre phenomenon of giant seagulls which are stealing aspects of people’s lives and depositing the stolen things in a strange nest. In this nest, Nal finds pennies from the future, tickets to events that have yet to occur, canceled passports and more. He deduces these creatures are in someway manipulating the lives of everyone in the town, which gives the story a layered texture in which the reader can imagine several alternate universes overlapping on top of one another. The Seagull Army in this story reminded me a little bit of the Trickster’s Brigade from the Doctor Who universe! Russell describes the seagull’s machinations this way:

…Warping people’s futures into some new and terrible shape, just by stealing these smallest linchpins from their presents.

If the disappearance of objects is the speculative premise behind Karen Russell’s story, then Aimee Bender’s “Americca” seems to present the opposite. This tale focuses on a family who suddenly discovers new objects creeping into their home, objects they never purchased and never owned to begin with. It starts with an extra tube of toothpaste, and then becomes more and more bizarre. The narrator’s sister, Hannah says at one point that the home as been “back-wards robbed” insofar as what the young girls believe to be “ghosts” are giving the household objects which they don’t seem to need or want. These gifts from the ghosts aren’t necessarily useful either, but sometimes present a slightly more idealized version of the things the family already owns. My favorite example of this is when the main character insists that her mother buy her an over-sized cap featuring an octopus. The narrator loves the fact that the cap doesn’t fit her just right, but in the morning after she first gets it, another octopus cap appears on her dresser, this time, one that fits. This is probably the most affecting and wonderful moment in the story, where the main character grapples not only with the decision of what to do, but also how to feel:

I had two now. One, two. They were both exactly the same but I kept saying right hand, right hand, in my head, so I’d remember which one I’d bought because that was the one I wanted. I didn’t want another octopus cap. It was about this particular right-hand octopus cap; that was the one I had fallen in love with. Somehow, it made me feel so sad, to have two. So sad I thought I couldn’t stand it.

Sometimes the speculative elements aren’t entirely explained, like in Rikki Ducorent’s “The Dickmare” a story that seems to be told from the perspective of some kind of underwater crab-like creature, complete with shell-shedding and references to “The High Clam.” Do you need to understand what kind of creature is actually narrating? Probably not. Though I’m confident it’s not human.

There are so many more, and I really can’t spoil all of them for you. I will say Julia Slavin’s “Drive-Through House” might have one of the best titles of any short story I’ve ever read. Mostly because it tells you exactly what the story is going to be about: a woman who lives in a drive-through house. There are cars in her kitchen, cars in in pantry, and she has to cross the road in her nightgown in the middle of the night to get from room to room. Wonderful.

The authors in this anthology aren’t putting speculative fiction elements into these stories for the sake of being edgy or interesting. Instead, I got the sense these stories sort of demanded to exist. They crept over from a bizarro dimension and into the brains of these awesome writers. I don’t normally like sounding like a commercial or anything, but this book would make a stellar gift because if you gave it to the kind of person that digs this stuff, they would be ridiculously thankful. Miranda July’s contribution to the book, “Oranges” asks this question: are you anyone’s favorite person? I bet anyone you give this book to will consider you theirs.

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com.