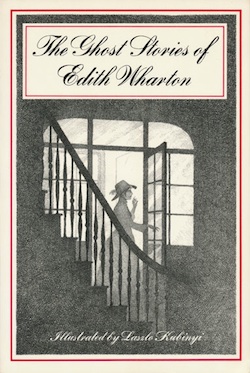

I was perusing the excellent used bookstore in my neighborhood and encountered The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton. It was a 1973 paperback version from Scribner, and, flipping the pages, it was filled with illustrations, all by the artist Laszlo Kubinyi (like this one, from the cover). I’d read a few Edith Wharton novels, but I hadn’t become enraptured with her work until I read this book. After I read it, my notion of the ghost story changed, and I’ve become a Wharton enthusiast.

I’ve always been a person who’s easily spooked. Zombies and serial killers don’t get me – it’s ghosts. Demons, spirits. (Actually, this is not true. Buffalo Bill and 28 Days Later totally get me. But mainly, it’s ghosts.) Maybe it’s my suburban childhood filled with TV and movies, and too many stories told at sleep-away camp around a dying campfire. The rigid societal mores Edith Wharton traveled in stuck with me most about her novels. After reading her ghost stories I couldn’t help but imagine Wharton herself, in The Mount, her giant house, locked in her terrible marriage, living in that incredibly rigid age, having her desperate love affair. Much has been written about that age, but until I read this it didn’t capture my imagination.

In “Afterward,” Americans Mary and Ned Boyne take up residence in England, after Ned has earned a fortune from a business deal involving a mining interest. They settle at Lyng, a classic English manor house with a “wide hooded fireplace” and “black oak rafters,” where they hope to linger in solitude. One day, Mary unearths a staircase leading to the roof. She and Ned gaze out at the downs, and suddenly spy a mysterious stranger who unnerves Ned. A few weeks later, when Mary is out, a stranger—the same?—comes to call on Ned, and Ned vanishes. For good. Gasp!

Only weeks later—afterward, from the title—when a former business associate of Ned’s arrives, is it revealed that the stranger was the ghost of Robert Elwell, a young man Ned may have cheated out of his share of the mining fortune. Elwell is dead by his own hand, and Mary swoons in the library, chilled to the bone, only then realizing that the dead man’s ghost has taken revenge on her husband: “She felt the walls of books rush toward her, like inward falling ruins.” And of course, there’s a twist of such brutality that “Afterward” could only be Edith Wharton’s. Let’s just say it involves dying twice.

I thought of her sitting in that quiet, icy house, writing these stories one after another, trying to adhere to the conventions of what, at the time, did in fact amount to a genre. The essence of a ghost story was a sense of veracity. It had to be true! Or, rather, feel true. There are eleven stories in this volume, but I love to think that there were others on paper that she balled up and tossed, trying over and over to get them right, so that the reader would believe each was true. I became enthralled with the idea that someone who was capable of writing something with the drama and energy and romance of The Age of Innocence also amused herself concocting ghost stories, trying to scare herself as much as the reader. She was trying to follow a convention – but also, muck about with convention, like a true original.

I was reminded of watching ancient episodes of Doctor Who with my brother while my parents were out – us saying to each other, “that was a good one,” talking about that magic that happens, of being transported to another world altogether, when something of a particular genre does what only that genre can do. I kept thinking how Wharton, too, loved that thing in ghost stories, she loved reading them and getting the whim-whams, the heebie jeebies. If there was a particularly popular genre of her day, it was the ghost story. She was a fan.

And, like the best of any genre, these Wharton stories do that very thing that only ghost stories can do – when the light goes off and you’re alone trying to sleep, you look up at the dark corner of the bedroom, unable to shake the last tale you read, and feel some slithery, other-y presence, and on the light goes.

In “Kerfol,” a man makes his way through the French countryside, half-lost, to visit an estate of that name, passing through a lane of trees he can’t name: “If ever I saw an avenue that unmistakably led to something, it was the avenue at Kerfol. My heart beat a little as I began to walk down it.” Soon after, he discovers the estate’s hideous secrets, after encountering a pack of murdered, ghostly dogs.

In the preface to this book Wharton talks about veracity: “The good ones bring their own proof of their ghostliness, and no other evidence is needed.” When it’s really good, she writes, it relies on its “thermometrical quality; if it sends a cold shiver down one’s spine, it has done its job and done it well.” I like to think also that Wharton had encountered a ghost or two, and was not only trying to convince the readers of her tales’ veracity, but herself of their lack of veracity, writing so as to shake off that shiver, so particular to the ghost story.

But what’s also thrilling about these stories is that Wharton still does what only she can do: a delightfully wicked skewering of her culture. The ghost in “The Lady’s Maid’s Bell” has revenge in mind against a doltish, tyrannical husband. In “Mr. Jones,” Lady Jane Lynke inherits an estate unexpectedly, and can’t make sense of how to get the servants to pay attention to her – especially since the caretaker has been dead for decades, but still hangs around giving orders. And in every story, ceremony eerily haunts the characters, just like in Wharton’s other work. In her other work, the ghosts are all human – she can’t really unleash the ghosts into their true terrifying forms, but in this collection she does. I thought of the Van Der Luydens, from The Age of Innocence, standing on convention so stiff they might as well be dead. Here, it’s obvious she was having great fun – “Mr. Jones” is a perfect Halloween interlude for all you Downton Abbey fans.

Reading this book felt as though someone had given it just to me – I’m hacking away at my own stories, about people in an intolerant society, and with, of course, ghosts. It gave me an idea of what ghost stories are supposed to do for us – show us that the apparatuses that we thought moved the world, the underpinnings of that world, are not what we thought. They’re spiritual, or, rather, of spirits, and the actions of plain men and women and our moral and amoral doings are no match for the specters lingering around us.

Anne Ray’s fiction has been published in Gulf Coast, LIT, Cut Bank, Opium, and Conduit. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College and was the recipient of the 2011 Montana Prize in Fiction. She can be found at @AnneRay347.

*brrr*