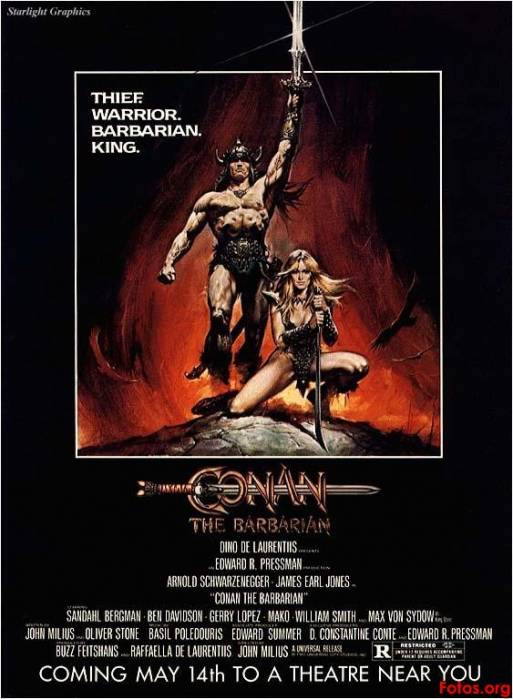

This is the first of two reflections on the Arnold Schwarzenegger Conan films from the 1980s. (Check back tomorrow on Tor.com for the second one.) Both bear titles that reference the lines from Robert E. Howard’s first published Conan story, “The Phoenix on the Sword,” made famous as the epigraph to issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian comic series: “Hither came Conan the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.” We’ll get to the gigantic mirth soon enough with Conan the Destroyer. For now, we’ll focus on the gigantic melancholies of the first film, John Milius’s Conan the Barbarian, from 1982.

I saw Conan the Barbarian late in its theatrical run, despite being only eleven years old, thanks to my father’s willingness to smuggle me in to a drive-in showing beneath a sleeping bag in the king-cab of his truck. Dutiful father he was, he made me close my eyes for the nudity, and murmur something like, “Don’t tell your mother about that,” for all the gore.

I remember being rather taken with the spectacle of the film, but unable to articulate why it didn’t bear the same ad nauseum repeat viewings that the far inferior, but more fun Sword and the Sorcerer did. If you’d given me the choice between watching Albert Pyun’s splatterfest of schlock and sorcery and Milius’s brooding barbarian bent on vendetta, I’d have chosen the triple-bladed-sword every time. Repeat viewings of both, along with the eventual dog-earing of my Ace Conan paperbacks lead me to the conclusion that I’d be hoping to see Conan on the screen when I went to see Schwarzenegger. What I got was a somber Cimmerian, and so was disappointed. I had no expectations of Pyun’s hyperbolized hero, Talon (played by Lee Horsley of Matt Houston fame), but got a character who, while lacking the mighty thews we’d come to expect of Conan (thanks largely Frank Frazetta’s cover paintings, and then John Buscema and Ernie Chan, who put Conan on a regimen of steroids), had the sharp mind of the thief, the propensity for violence of the reaver and slayer, and a combination of melancholy and mirth that Conan exhibited throughout Howard’s writing. In short, I realized that Milius’ Conan wasn’t necessarily Howard’s Conan, despite the film’s narrative nods to Howard’s stories, from the crucifixion scene (“A Witch Shall Be Born”) to Valeria’s promise to return from the grave (“Queen of the Black Coast”).

This isn’t a bad thing: by the time Conan the Barbarian hit theaters, Howard’s character was half a century old, and had taken on a life of his own beyond his creator’s writing. First we had the pastiches, edits, and new tales of L. Sprague De Camp, Bjorn Nyberg, Lin Carter, and later a host of other fantasy writers, including SF heavyweight Poul Anderson. Then came the Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian comic series and its adult contemporary, Savage Sword of Conan, which adapted both the original REH stories as well as the pastiches, in addition to adding its own new stories and characters to the Conan mythology. So despite protestations by REH purists, by the time Oliver Stone and John Milius wrote the script for Conan the Barbarian, there was no uniform character anymore, but rather a toolbox to draw from: within the comic books alone there were multiple Conans to choose from: the lean, wiry youth of Barry-Windsor Smith, or the hulking bearskin-clad brute of John Buscema?

What appears onscreen in Milius’s film seems to be influenced more by Frazetta and Buscema’s artwork than Howard’s character. The Conan of REH is clever and articulate. The Conan of Milius is often childlike and taciturn: he is discovering the world after years of being shut away from it. While the young Conan fanboy was irritated by this, the grownup literary scholar is comfortable with it. I appreciate the two Conans for different reasons.

What I love about the film, all comparisons to source material aside, is exactly Conan’s silence. Milius has stated he chose Schwarzenegger for exactly this reason. The movie replaces dialogue with two things: imagery, and Basil Pouledouris’s score, which evokes shades of Wagner and Orff. Numerous critics have commented on the opera-like quality of the score, and of the film in general. Consider the moment when Thulsa Doom kills Conan’s mother in the opening. Music and image tell the story: there is no dialogue needed. Conan’s mother has no witty last words. Action is everything, right down to the youthful Conan looking at his hand, where only a moment ago his mother’s hand had been. I’m not sure if Milius intended for this visual poetry, but there’s an echo later in the film when Conan stares at different swords in his hand. Thulsa Doom steals away his mother’s hand, and leaves it empty. Conan fills it with the sword, which is ultimately Thulsa Doom’s undoing.

I also love how gritty it is. In the day-glo 1980s, this film has a remarkably desaturated color palette. There is no attempt to realize a standard fantasy world: this is no place for the knights of Camelot in Boorman’s Excalibur. In Milius’s Hyborean Age, things rust, rot, and reek. The sex isn’t always glossy and erotic: sometimes it’s just rutting in the dirt. The fights are well-choregraphed, but there’s a raw urgency to them. Early scenes of Conan’s gladiator days are a barrage of brutality, actors working hard to literally hit their mark, to strike a bag of blood hidden in a costume or behind an actor’s head, so that the combat never looks entirely polished. In one of the only relevant comments made during the tedious DVD commentary with Milius and Schwarzenegger, they remark on how you’d never get away with the sort of stunt work this film employs. It’s obvious that Schwarzenegger’s sword actually hits Ben Davidson’s shoulder in the final battle, bursting a blood pack in a fountain of gore. It’s all CGI blood these days, and there’s something satisfyingly primal and visceral about the fighting here.

All this said, I’ll concede it isn’t a great film. It’s a beautiful film with a beautiful score. The costuming, sets, and locations are well-captured by Duke Callaghan’s cinematography. The shot of Thulsa Doom’s horde riding towards the low-angle camera from the Cimmerian forest is one of my favorites of all time. Whenever I hear the opening notes of “The Anvil of Crom,” I get shivers. But the acting is either atrocious or cut-rate, and contrary to many, I think James Earl Jones was terribly cast: he doesn’t so much steal scenes as seem to be slumming in them. The actors were hired for their physical prowess, not acting ability, which is both an advantage for the fight scenes and stunts, and a disadvantage in the moments when dramatic gravity is needed. Still, they work their craft in earnest, with Mako as the old wizard coming out as my favorite performance of the entire film.

I’m not a Schwarzenegger die-hard when it comes to Conan. He’s one of many Conans on my shelves, but in this film at least, he remains one of my favorites. When he runs wild-eyed at a mounted combatant, or flexes his muscles in bodypaint, he’s a formidable Conan. I love his glare back at Thulsa Doom’s fortress after Valeria’s death. Even my wife had to remark, “Someone’s gonna get their ass kicked.”

But I’m excited for the new film too. If it’s successful, it will mean a delightful inundation of shameless Conan marketing. In preparation for the new film, Conan the Barbarian was released to Blu-ray, which means that spectacular Pouledouris soundtrack will finally be heard in stereo.

Know, O prince, that between the years when Bakshi animated hobbits and Heavy Metal, and the years of the rise of Weta Workshop, there was an Age undreamed of, when fantasy movies lay spread across the world like cheap trash on the shelves – Ator with that guy from the Tarzan movie starring Bo Derek in the buff, Beastmaster, with the guy from V, Krull, a movie Liam Neeson played someone’s sidekick in, Deathstalker, with nudity so endless adolescent boys even stopped caring. Hither came Conan the Barbarian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the direct-to-video pretenders under his sandalled feet. It might not hold up next to today’s fantasy fare, but in ’82, it was the best thing going.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.