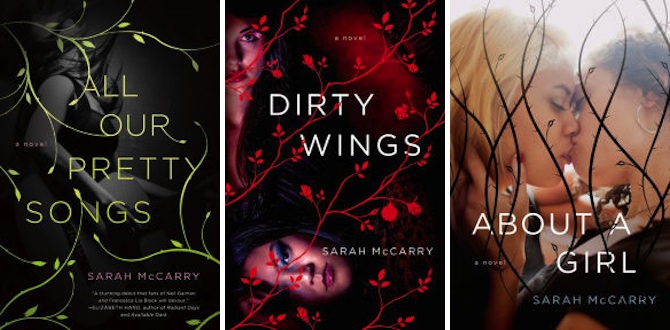

Sarah McCarry is a writer and publisher whose Metamorphoses Trilogy, a YA series loosely based on tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, was completed this year. The novels—All Our Pretty Songs, Dirty Wings, and About a Girl—follow three generations of a family through a kaleidoscopic whirl of myth, fantasy, goth and grunge. In addition to writing beautiful and addictive fantasies, Sarah publishes innovative writing through Guillotine Press.

The two of us sat down for an online chat one afternoon, me in California, Sarah in New York.

Hi Sarah!

HI SOFIA

Can we talk about girl monsters?

Yes! What are your favorite kinds? Taxonomies, habits, habitats, diets etc.

They have no diets. Their habits are bad. I’m thinking of course of the wonderful girl monsters from your Metamorphoses Trilogy—girls who party and run away and live on the streets and make art and lose each other and save each other. Your characters are bewitching and dangerous and sometimes downright terrible. What draws you to these girls?

What draws me to those girls—that’s the central question of everything I make, I think (and also a lot of my personal life, ha). I always wanted to make my own trouble. I grew up in a very conservative environment—religious, protective family; rural military town—so finding stories in the real world that matched the stories I wanted to be living was a transformative experience for me. I assumed, growing up, that you had to be a boy to live the kind of life I wanted, and so I spent most of my time with boys; meeting women who were trouble, who were monsters making their own lives, was like falling into magic. I was one of those girls for a while. I’ve had those girls in my life since I left home. I think monster stories are fundamentally about living freely, about the desire for an autonomous life when your own story doesn’t correspond with what the dominant culture identifies as deserving of that kind of autonomy. Nobody fucks with the Gorgon. She might be lonely sometimes, but she makes the rules.

This leads me to Ovid, and The Metamorphoses, and the relationship of that network of stories to the ones you’re telling. You work with a number of tales and characters from classical Greek mythology in the trilogy—Orpheus and Eurydice, Persephone, Medea. I have my own reasons for thinking this is perfect, but what are yours? Especially since we’re talking about the cultural dominance of certain stories, and here you are riffing on this very high-culture text. Why Ovid?

The most obvious and instinctive answer for me is that I grew up with them. I mean, most of us in the West grew up with them whether or not we wanted to, right, or whether or not we also grew up with the stories of non-dominant cultures, or our own cultures, or whatever. They’re the foundation of THE CANON in all its tedious un-glory. But there are so many cracks in those stories where what are basically accounts of power transactions and property transfers between men (the property being sometimes literal property and sometimes, you know, somebody’s wife) split open and all this messy bloody witch gore pours out. There’s so much female power in those stories, so many women with agency and magic and their own authority to influence and rewrite events. The Fates, the Kindly Ones, Medusa, Medea, Clytemnestra, Procne and Philomela—I mean, your husband rapes your sister, you feed him his kids; those women weren’t fooling around. I read all of that slippage as being in spite, rather than because, of Ovid. He likes gossip but he doesn’t much like women. He’s not particularly interested in feminist subversions. If you read between the lines, though, all the good stuff is there.

A lot of that mythology also incorporates themes that I think of as universal—the journey into (and hopefully out of) darkness being one that I’m especially interested in.

And yeah, the high/low contrast fascinates me too. Ovid is quite sacred in academic circles when he’s really sort of like the InTouch of his time. And my books are published as YA, which we all know is not a serious category of anything whatsoever, and they’re about girls, and they’re fantasy.

Fantasy! Ew!

I KNOW. It’s gross, especially when it has got girls in it. So I am thinking now about how inhabiting and subverting these canonical stories is good imaginative practice for the larger work of thinking about different ways to live inside structures to which we do not consent. Walidah Imarishah has a lot of wonderful writing on speculative fiction as a tool for navigating and building radical futures. And for me—we don’t get to live outside capitalism, we don’t get to live outside colonialism or neocolonialism or neoliberalism or any of these other constructs and empires; we don’t get to opt out—and so on the small scale, finding the cracks in these supposedly hegemonic and patriarchal sources on which so much of the Western canon is founded echoes the practice of imagining new ways to survive power and build allegiances across or beneath or around networks of power. And I wonder if you have thoughts about that, and if for you working with myth and in particular a mythology that doesn’t get circulated by the dominant culture, or is routinely exoticized if it does circulate, has anything to do with that kind of practice. Like, why art, Sofia? What are we doing? Maybe we should be in a battlefield or running to the woods. I don’t know.

Woods yes. Battlefield no! But to answer your question, or start answering it… We live by and through stories. We are always in the midst of this welter of images. As you say, there’s no “outside,” no neutral ground. So you work where you are. I’ve thought about this a lot—can an image be ruined? Is there something, let’s say a heavily exoticized image, like a desert nomad, or to take an example from your trilogy, a beautiful damned girl—is there an image so abused that it’s irreparably tainted? My own feeling is that the search for purity is a fool’s errand in this fallen world, so in a sense the question is moot. Yes, the image is tainted. You use it anyway, you do what you can with it. It’s either that or shut up altogether, especially if that abused image represents, in some way, yourself.

I also love what you say about finding those cracks, those gaps. I think we should steal wildly and generously from everything around us. Generous theft! I think this is possible! So you go to something like The Metamorphoses, and along with this burdensome patriarchal culture you find things that speak to you, the gaps and moments of resistance and certain images that move you, and you steal them without holding back, with a kind of submersion in the “enemy” text, an embrace. Because the enemy is also a lover.

Yes! This is why Twilight did so well, ha, although I do not think Stephenie Meyer was necessarily advancing an anticapitalist project. I did think a lot about the danger of those burdensome creatures, the ruined images, when I was working on these books—is Aurora too beautiful and too damned? Is Raoul a noble savage? Is Jack a caricature? And I don’t think I am the right person to say yes or no to those questions, obviously; that’s for the reader to decide. I hope the framework of the stories supports readings other than “these characters are lazy tropes.” Aurora in particular was tricky territory for me, as someone who has done my own share of falling in love with darkness—I’ve always come back, but Persephone and Eurydice still resonate for a reason. I think fiction is also a useful place to look at those questions of love and darkness and longing. And we do live through stories, but telling a story one way can give us the freedom to live the story to a different ending.

Something I think is so important in the trilogy, and also part of why Ovid is perfect for it, is that the danger is real. You’re writing about gods and monsters, and there’s a certain glamour to that, for the characters and for the reader, but you know, gods and monsters represent real risks. You give us all the magic of sex, drugs and rock n’ roll but there’s also this harsh reality—that this enchantment is a gateway to the land of the dead, and not everybody who crosses over returns. Not everybody comes back from drug use, for example. Your characters learn that, and they also learn that, as Maddy says in About a Girl, “Becoming a monster is only one way to survive.”

I want to ask you about the cover of About a Girl—because isn’t this the first mass-market YA cover to show two girls kissing??

Yeah, amen to the above: the underworld looks like a good party from a distance, but it’s not a party that everybody gets to leave.

It’s the first cover of a YA novel published by a Big 5 publisher (Big 4 now? I can’t keep track) to feature two girls kissing, yes! It came about because I am a belligerent pest, is the short version of the story. I am still delighted about that.

So I’m talking to An Historic Personage is what you’re saying.

I do my best.

I wanted to ask you about personal history—the landscapes and influences that fill your work. The trilogy seems so steeped in a sort of youth ethos of the Pacific Northwest, and California too. And it’s crisscrossed by many strands of literature, not just Ovid, and music and art and astronomy. Can you talk about influences?

I grew up in the Pacific Northwest in a small town outside of Seattle in the heyday of grunge and its aftermath. I’d been interested in a long time in incorporating that particular mythology of my adolescence into something larger. I have friends who knew Kurt Cobain—which I somehow managed not to think about while I was working on the first book, thankfully—but at this point he’s very much a mythical figure in his own right and I chose to come at that from—I guess from a position of irreverence, to be honest. The Seattle in the books doesn’t exist, of course, and never did; it’s Seattle through the lens of that mythology. But most of the places in the books are real, and some of that magic really was around when I was a kid sweating out my demons at rock shows, and Kurt Cobain did exert this almost religious influence over a lot of people I knew. I still remember what I was doing when I found out he had died.

I haven’t found that many books that work with the Northwest in that way, which surprises me—there’s so much there. So much history and myth and plenty of trauma and all the ingredients for quite good, messy stories. I would love it if Caitlin Kiernan moved to the Olympic Peninsula and started writing creepy forest books. Lynda Barry’s novel Cruddy is one of the best mythical books about old Seattle that I can think of off the top of my head. Amazon has pretty much destroyed any bit of the city that I loved, but the old bones are still there, under all the shitty condos and craft beer bars and stoned tech bros.

I have to quote this part where Jack plays music in All Our Pretty Songs. “His music is like nothing I have ever heard,” the narrator says: “I can feel it running all through me. It is open space and mountains … Snowmelt in spring, bears lumbering awake as the rivers swell, my own body stirring as though all my life has been a long winter slumbered away and I’m only now coming into the day-lit world. As he plays the party stills. Birds flutter out of the trees to land at his feet and he is haloed in dragonflies and even the moonlight gathers around him as though the sky itself is listening.”

This is an amazing moment, a moment of transformation through music for the narrator. I love the shift from an internal to an external landscape, from her feelings about the music and the images it calls up to its effect on animals right there, in the real world. The speaker is an unnamed character—the one who becomes Tally’s Aunt Beast in About a Girl. I think of her as Beast. One of the animals. She is never named, is she?

She isn’t, no. (Some people were really mad about that, which I thought was sweet.) Almost everyone’s name in the books has some kind of significance, or is an allusion to something, and I didn’t want to make it obvious what her role in the story would turn out to be. She is very connected to the natural world, especially in the first book, and in the third book she and Henry and Raoul form a net of love that’s always there to catch Tally when she falls. Tally, in the end, is able to make better decisions than her mothers and her grandmothers, because she has the safety of their love.

Thank you Sarah! I just want to ask one more thing: now that the trilogy’s complete, what’s next for you?

I’m working on something completely different. But it’s a secret.

Fair enough! Thanks for this wonderful chat.

THANK YOU FOR THESE SO GOOD QUESTIONS

THIS WAS REALLY A PLEASURE

<3

Sofia Samatar is the author of the novel A Stranger in Olondria and winner of the John W. Campbell Award, the Crawford Award, the British Fantasy Award, and the World Fantasy Award. Her second book, The Winged Histories, is forthcoming in 2016 from Small Beer Press. She co-edits the journal Interfictions and lives in California.

Sarah McCarry (@therejectionist / www.therejectionist.com) is the author of the Metamorphoses Trilogy, which includes All Our Pretty Songs, Dirty Wings, and About a Girl, and the editor and publisher of Guillotine, a chapbook series dedicated to revolutionary nonfiction.