In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

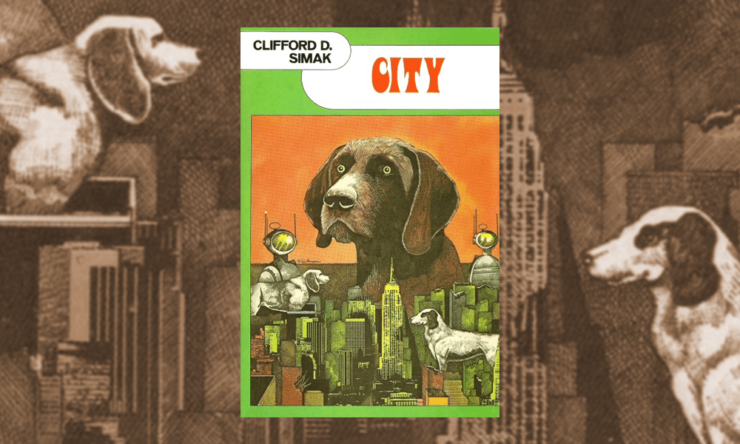

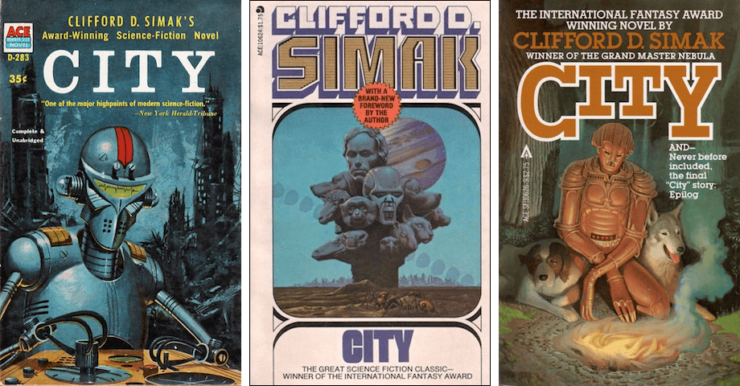

Sometimes, a book hits you like a ton of bricks. That’s what happened to me when I read City by Clifford D. Simak. It didn’t have a lot of adventure, or mighty heroes, chases, or battles in it, but I still found it absolutely enthralling. The humans are probably the least interesting characters in the book, with a collection of robots, dogs, ants, and other creatures stealing the stage. It’s one of the first books I ever encountered that dealt with the ultimate fate of the human race, and left a big impression on my younger self. Re-reading it reminded me how much I enjoyed Simak’s fiction. His work is not as well remembered as it should be, and hopefully this review will do a little bit to rectify that problem.

Sometimes, re-reading a book will bring you back to where you first read it; for me, City is definitely one of those books. I was at Boy Scout camp for the first time. I still remember the smell of the pine needles and oak leaves, along with the musty smell of army surplus canvas tents. I was feeling a bit homesick, and decided to do some reading—a book with a robot on the cover I had borrowed from my dad. This might not have been a good idea, as I wasn’t in the best frame of mind to be reading about the end of civilization. But I was in good hands, as Simak’s writing has a warmth in it that makes even the weightiest of subjects seem comfortable. His work was something new to me: stories that weren’t wrapped around science and technology, heroes who didn’t wield blasters or wrenches, and plots not driven by action or violence. If anything, framed as it was as a series of tales told around campfires, City felt like the stuff of legend—not a legend filled with past gods, but a legend of the future.

About the Author

Clifford D. Simak (1904-1988) was a career newspaper writer, with most of his professional life spent at the Minneapolis Star and Tribune. His science fiction writing career spanned more than fifty years, from the early 1930s until the 1980s. He was a favorite author in Astounding/Analog for decades, and also sold a number of stories to Galaxy. The fix-up novel City is his most widely known work.

His writing was notable for its frequent celebration of rural Midwestern values and a wry sense of humor. He did not dwell on science, instead focusing on the human impacts of scientific developments, or encounters with other beings. He often explored the reactions that ordinary folks might have upon facing extraordinary circumstances. His stories were gentle in nature, and less prone to violence than those of other writers. He was reportedly well-liked by his peers, and enjoyed fishing in his spare time.

Among Simak’s awards were a Best Novelette Hugo for “The Big Front Yard” in 1952, a Best Novel Hugo for Way Station in 1964, and a Best Short Story Hugo and Nebula for “Grotto of the Dancing Deer” in 1981. He was selected to be a SFWA Grand Master in 1977, only the third author selected for that honor, following Robert A. Heinlein and Jack Williamson. As with many authors who were writing during the early 20th Century, some works by Simak can be found on Project Gutenberg.

Cities of Tomorrow

I had long been confused why a book called City tells a story about the end of human cities. In researching this column, however, I found an article on the theme of cities in the always excellent Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (which you can read here). In that article, I found only a few books and stories listed that I’ve read—perhaps because as a small-town boy, the idea of cities did not appeal to me. When cities appear in science fiction, they frequently appear in a negative light, or are included in stories about destruction or decay. Cities are portrayed as sources of stress, places where people are hemmed in, hungry or desperate. Moreover, they often appear in ruins, and figuring out what led to this urban destruction is the driving force for the plot. Arthur C. Clarke’s The City and the Stars is one of the few books mentioned in the article that I have read, and that story is infused with melancholy. In the books I liked best as a young reader, cities often figured as the place where adventures would start—but after gathering together knowledge and supplies, the first thing the protagonists generally do is leave in search of adventure, or to seek riches, or to do battle, or to explore. Like many people, I have mixed views on the crowded environments of most cities, and it seems that Clifford Simak was one of those people, as well, judging by his work.

City

City is a fix-up novel, collecting a series of related stories that initially appeared in Astounding and elsewhere in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The framing narrative treats these stories as ancient legends of dubious origins. Now, I have read a lot of fix-ups over the years, and this frame is far and away my favorite. I liked it upon my first reading, and enjoyed it even more today. It describes the tellers of these eight stories as dogs, who treat the human race as mythical beings and suggest the stories are allegorical. Amusingly, the scholars who debate the origin of the ancient tales have names like “Bounce,” “Rover,” and “Tige,” with Tige being eccentric enough to believe that the humans in the tales might have actually existed. I have read more than one book about theology in my life, and these doggish scholars remind me of real-world biblical historians, trying to compare the tales of the Bible with historical records to determine what is factual and what is legend and parable.

Just a word of caution before I go forward; in most of my reviews, I avoid spoilers and usually don’t discuss the endings of the various books I cover here. In this column, however, I will discuss each of the eight tales. Those who wish to avoid spoilers and want to experience the book for the first time with an open mind may want to skip ahead to the “Final Thoughts” section.

The first tale, called “City” like the novel, is about the end of human cities on Earth. Personal aircraft and helicopters, along with cheap atomic power, industrial hydroponic farming, and factory-built homes, have created an environment where everyone can move to a country estate. Inner cities and even close-in suburbs are being abandoned. The threat of atomic war is diminishing because there are no dense population centers to be threatened. We meet John Webster (the first of many members of the Webster family that we will spend time with in these stories), who speaks truth to power and loses his job, only to be hired by the World Council, resolving disputes between the remnants of the city government and squatters. The details are different, and the driving force here is more communications than transportation, but we see can see similar forces at play in our current society, where the internet is creating opportunities for workers and companies to scatter more widely across the map.

In the second tale, “Huddling Place,” Jerome Webster, a surgeon, lives on the country estate where his family has now thrived for generations. For the first time we meet Jenkins, the robot who serves the Webster family. Jerome spent a number of years on Mars, befriending a Martian named Juwain, a brilliant philosopher whose important work is nearly completed. But now Juwain is ill, and only Jerome can save him. Jerome finds that he has become agoraphobic, and cannot bring himself to travel to Mars, or even to leave the family home. The new homes of mankind have become places to hide.

The third tale, “Census,” is where dogs first enter the story, much to the delight of the dogs who recount these tales in the frame narrative. The world government has noted some strange trends emerging, and the story follows a census-taker and investigator, Richard Grant. Grant is understandably surprised to meet a talking dog in his travels. One of the Webster family, Bruce, has been experimenting with dogs, altering them surgically so that they can speak, and inventing contact lenses that enable them to read (traits that are then inherited by other dogs, through means that are not explained). Grant is also looking for human mutants, and finds one named Joe who has encouraged ants to develop a civilization (again, through means not plausibly explained).

The fourth tale, “Desertion,” is one that baffles doggish scholars because it takes place on Jupiter, a place described as another world. A way has been developed to turn men into “lopers,” creatures indigenous to the planet, but none of the subjects are returning. A brave man named Fowler decides to try one more time, using himself as a test subject; he also transforms his aging dog, Towser. The two of them find Jupiter to be a happy paradise, one they do not want to leave.

In the next tale, “Paradise,” Fowler finds himself driven by duty to return to Earth. He tells of the paradise he found on Jupiter, and Tyler Webster, who works for the world government, tries to block the information, afraid that most of humanity will seek transformation. The mutant Joe emerges again, having solved the mystery of Juwain’s lost philosophy, which gives Fowler a means of sharing his experiences. Only the murder of Fowler will prevent this, and Tyler is unwilling to be the first person in many years to kill. Thus, most of the human race flees to the paradise that life on Jupiter offers.

The sixth tale, “Hobbies,” introduces us to the dog Ebenezer, who is slacking in his duties to listen for “cobblies,” creatures from parallel worlds. The dogs are bringing their civilization to other creatures, and trying to create a world where there is no killing. Meanwhile, in Geneva, the last human city, Jon Webster has found a defensive device that will seal off the city. Its inhabitants are increasingly seeking oblivion, either in worlds of virtual reality or by sleeping in suspended animation. Jon visits the old Webster house, and finds the faithful robot Jenkins still keeping the house and guiding the dogs. Deciding that the dogs are better off without human guidance, he returns to Geneva, seals the city off from the world, and goes into suspended animation.

Buy the Book

The City in the Middle of the Night

The penultimate tale is “Aesop,” a tale that shares a title with another literary fragment found by doggish scholars. This story shows us that the dogs have forgotten “man,” and now call humans “websters.” The dogs have discovered that parallel worlds do exist (which explains why they have been seemingly barking at nothing, puzzling humans for uncounted centuries). The cobblies who inhabit some of those parallel worlds are crossing over and murdering animals. Doggish efforts to bring their ways to other animals are progressing. A young webster has re-invented the bow and arrow, accidently killing a bird with it, and then driving away a cobbly that has killed a wolf. Jenkins, now in possession of a new robot body given to him by the dogs, decides that humans must be removed from the world for the benefit of the doggish culture, and despairs that humanity will never unlearn their propensity toward violence. He takes the remaining humans on Earth to the cobbly world in order to eradicate that threat.

The final story of the collection, “The Simple Way,” is set 5,000 years after the others. The scholarly dogs tend to doubt its authenticity because it feels different from the other tales, and because it describes a world shared by both dogs and ants. We meet a racoon, Archie, who has a robot named Rufus. All dogs and many other animals now have robots that help them in situations where hands are needed. Rufus tells Archie he must go help the ants, whose mysterious city has been spreading. Archie thinks a “flea,” ticking like a machine, may have something to do with Rufus’ actions. The dog Homer goes to visit a group of “wild” robots to try to figure out what’s happening. A robot named Andrew claims to be old enough to remember humanity before most people fled to Jupiter; he tells of a mutant named Joe, who helped ants create a civilization, and then destroyed it by kicking over their anthill. Jenkins returns to Webster House, after transporting the humans to the cobbly world in the previous story. Apparently, after dealing with the cobbly menace, those humans died out. Homer goes to Jenkins for a solution to the ant encroachment. Jenkins decides he needs human guidance, and awakens the sleeping Jon Webster in Geneva, who tells him that dealing with ants is easy—all you have to do is poison them. Jenkins thanks him, and lets him go back to sleep. Horrified by the thought of mass killing, he decides the dogs will have to lose a world.

There is a lot going on in these deceptively simple tales. When I first read them as a youngster, I took for granted that a single family could be involved in all the major turning points in human history. As an older reader, I realize how improbable that would be. But I’ve also had learned something about allegory in the interim—and it’s on that level that this collection of tales works. Like the Aesop’s Fables mentioned in the text, each of the stories is a morality tale offering a lesson or observation about the human condition. There is a lot of pessimism regarding human nature, but it is balanced out by the fact that our descendants, the dogs and robots, show every sign of being able to rise above human shortcomings. And there is something heartwarming about a new civilization that gathers around campfires to tell each other such stories. As a long-time dog owner, I am not someone who sees the world “going to the dogs” as a bad thing.

Final Thoughts

City is one of my favorite books, and a second reading has only strengthened that opinion. The book is pessimistic about the human condition, but offers hope as well. And of course, this book is just one of many thought-provoking and entertaining works that Clifford Simak penned in his lifetime—I would urge everyone who hasn’t been exposed to his work to seek it out. Finding a copy of City would be a good start, and in addition to his novels, his short fiction has been frequently anthologized. Simak is not remembered or celebrated as widely as some of his contemporaries, but that is no reflection on his work, which is just as powerful and engaging today as it was when it was first written.

And now, as always, it’s your turn to chime in: Have you read City, or any of Simak’s other tales? If so, what did you think, and what were your favorites? And what do you think of the idea of dogs taking over and inheriting the Earth?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.