In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field: books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

There are plenty of science fiction stories about soldiers, spacers, scientists, engineers, explorers, and adventurers, but not so many about merchants and traders. However, you could always count on Poul Anderson to do something different—he was a “Swiss Army Knife” kind of writer, with a wide variety of capabilities. He wrote both science fiction and fantasy, and his heroes filled pretty much every niche listed above. Anderson’s “Technic History” was a consistent backdrop for stories set over centuries, and of the most interesting periods in that history was when mankind was first spreading out among the stars, encountering alien intelligences and finding common ground with them. One of the most able heroes of this era is Nicholas van Rijn, a merchant captain who knows that there’s one language that all intelligences have in common: the language of trade.

The van Rijn stories portray a galaxy of diverse creatures where the common denominator is enlightened self-interest—or, if you are feeling less charitable, greed. They suggest that the desire to make a profit not only results in a more efficient economy, it provides a starting point where beings of all types can interact. In other words, the “invisible hand” of commerce posited by Adam Smith in his book The Wealth of Nations is seen as a constant throughout the universe, as predictable as gravity. The loosely organized Polesotechnic League Anderson created is a libertarian dream: the loosest of governments, which allows traders to pursue profits throughout the stars with almost no interference. It is no wonder that Anderson was awarded four Prometheus Awards from the Libertarian Futurist Society over the years, with one being an award for lifetime achievement. His work often celebrated libertarian ideals with an emphasis on minimal government, open markets, and personal freedoms.

These stories are the antithesis of the Star Trek universe, with its benevolent Federation, its lack of money, and its Prime Directive that outlaws interference with less advanced civilizations. When traders like Harry Mudd or the Ferengi did show up in Star Trek, they were usually presented in a negative light.

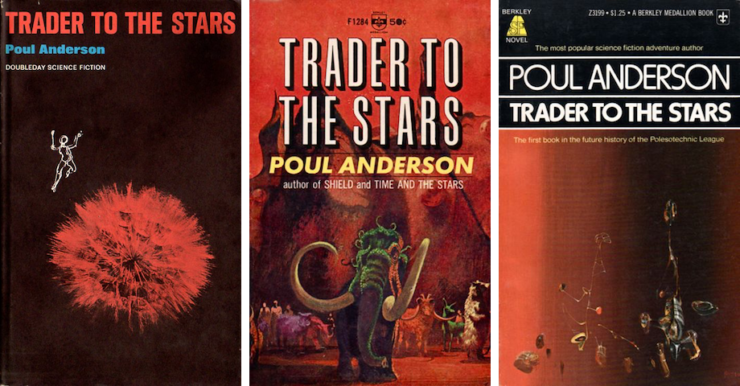

The edition I read for this review is a Berkley Medallion paperback edition from 1976, whose cover displayed impressionistic metallic artifacts floating in a reddish sky. The painting’s artist was not credited, but if it wasn’t by Paul Lehr, it was produced by someone who was replicating his style. The most recent publication of van Rijn’s adventures is a multi-volume set from Baen Books which contains all the stories from Anderson’s Technic History.

About the Author

Poul Anderson (1926-2001) was among the most prolific and versatile of American science fiction authors. His stories were rooted in the past, while staying on the cutting edge of science and astronomy. His prose could be clear and succinct when it needed to be, but also florid and poetical. His stories were peopled not by simple heroes and villains—black and white cookie-cutter representations of good and evil—but by protagonists and antagonists in shades of grey, with believable motivations. He was skilled at designing exoplanets, imagining the implications of their natures, and creating interesting creatures that might live on them.

Anderson was a founding member of Society for Creative Anachronism, an organization whose recreations of medieval weapons and combat helped many an author improve their fantasy novels. He also served as President of the Science Fiction Writers of America.

In a career that began in 1947, Anderson wrote over 80 novels and even more short pieces. His work garnered many awards, including seven Hugos, three Nebulas, a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master Award, induction into Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame, and a host of other honors.

As with many authors who were writing in the early 20th century, a number of works by Anderson can be found on Project Gutenberg.

Future Histories

Science fiction authors, especially those who tend to produce a body of individual stories and sprawling tales, are often fond of setting those tales in a common timeline. This practice has come to be known as developing a future history. Sometimes, the task is as simple as ensuring the tales are consistent with one another. Or sometimes, writers choose to use events from history as an analog for future events. But many authors attempt to project future developments in a more rigorous manner, utilizing political science, economic theory, and sociology to map out a plausible future. Authors have been especially fond of the theories of historians interested in long-term patterns of cultural growth and decline—historians such as Arnold Toynbee and Oswald Spengler.

One of the first future histories I encountered was in the work of Robert Heinlein, in a timeline contained in one of his books which showed where each of his stories fit the overall arc of history. Many of those stories drew their plots from events in American history. Another future history was presented in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, complete with a new field of “psychohistory.” Asimov was influenced by Edward Gibbon’s massive work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Other future histories can be found in the work of authors such as H. Beam Piper, Andre Norton, Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, Gregory Benford, David Brin, Stephen Baxter, and Lois McMaster Bujold—all authors whose work I have reviewed at some point in this column.

Poul Anderson was influenced by the work of historian John K. Hord, who analyzed the forces that cause civilizations to go through periods of growth and breakdown. Anderson used these theories to develop a detailed future timeline he called the “Technic History.” In the early part of this timeline, the days of the Polesotechnic League, master traders such as Nicholas van Rijn and his apprentice David Falkayn ranged throughout the galaxy, seeking opportunity. But this expansion led to the creation of an Empire that grew stagnant, and began to decay. It was during this later period when Imperial agent Captain Sir Dominic Flandry did his best to prop up the collapsing empire and stave off the long night of barbarism. I previously reviewed Anderson’s tales of Captain Sir Dominic Flandry here.

For further reading, the always excellent online Encyclopedia of Science fiction has a interesting article on History in SF, which can be found here.

Trader to the Stars

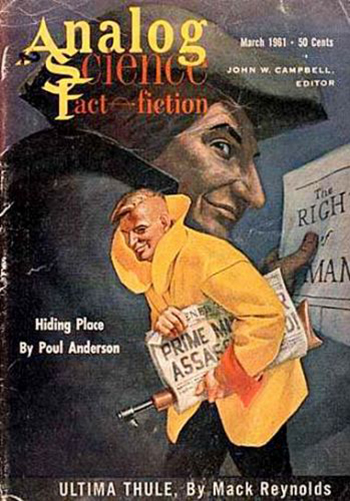

This book is not a novel, but instead is a collection of three longish stories that first appeared in Astounding/Analog Science Fiction magazine.

The first is “Hiding Place.” Master Trader Nicholas van Rijn is on his yacht, the Hebe G.B. (older folks will get the pun). He and his crew are on the run from the Adderkops, space pirates who have been terrorizing the region. Van Rijn and company have discovered the secret location of the Adderkop home planet, and the pirates are desperate to destroy him before he can bring the information to the authorities.

Van Rijn is anything but an ordinary character. He is the head of the Solar Spice & Liquors Company, one of the most powerful trading companies in human-dominated space. He is a heavyset, pot-bellied man with long black hair, a beard and handlebar moustache, and is often found wearing a sarong. His attitude toward women was offensive when the tales were written, and is even more grating to a current reader. Van Rijn makes a show of revering Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief who was crucified beside Jesus, mocking his own tendency toward greed. He constantly complains about his age, his weight, and his physical limitations, but repeatedly shows himself to be a gifted pilot and a man of action when needs require. He claims to be old and befuddled, but like my dad would say, he is “dumb like a fox.” He speaks in a mishmash of languages, with fractured syntax and mangled metaphors. He is objectionable and admirable at the same time, and always entertaining.

The van Rijn yacht is skippered by Captain Bahadur Torrance, a rather conventional man. He and Jeri, a young woman brought along to be van Rijn’s companion, develop a mutual attraction, which causes some complications with van Rijn. One aspect of Anderson’s work that I have always liked is that his future is very diverse, featuring characters representing many different races and nationalities. The yacht has a damaged engine, and will have difficulty making it home without being captured, so they search for another ship—but when they find one, it is an alien ship that attempts to escape, probably assuming that they are Adderkop pirates. When they board the ship, they find it is a zoo ship: a menagerie with specimens from a variety of races, none of which appear to be intelligent. There is no trace of the beings who piloted the ship because they have destroyed all clues to what they looked like and hidden among the other creatures. And there is no way to operate the ship and save themselves without solving that puzzle.

This type of puzzle story was common in Astounding/Analog during the period, and this tale is one of the better examples of the type. It is satisfying because the answer is obvious in hindsight, but not while you are reading. It is van Rijn who ultimately solves the puzzle, complaining all the way about what burdens he bears. He may appear lazy, but he gets things done.

The bridging material between this story and the next offers a description of the developments leading to this free-trading libertarian utopia:

Automation made manufacturing cheap, and the cost of energy nose-dived when the proton convertor was invented. Gravity control and the hyperdrive opened a galaxy to exploration. They also provided a safety valve: a citizen who found his government oppressive could usually emigrate elsewhere, a fact which strengthened the libertarian planets; their influence in turn loosened the bond of the older world.

Some folks might say that Anderson’s stories illustrate the benefits of a libertarian society. Others might argue that the choices made in building this universe were reverse engineered to support the author’s notions of a perfect society.

The second story, and longest in the collection, is “Territory.” Van Rijn is visiting the planet t’Kela when a native uprising drives the Earth contingent to escape in their two ships. Van Rijn and one woman, Joyce Davisson, are thought dead, but escape with the aid Uulobu, an older alien who is loyal to the Earthlings. The natives are one and a half meters tall and vaguely cat-like, and while the overall technology level on the planet is similar to the late Stone Age, there are some city dwellers, the “Ancients.” Many of the natives are nomadic, but the planet’s climate is out of balance and deteriorating, with a greenhouse effect that has collapsed. Anderson does a fantastic job creating a realistic ecology that is very different from Earth’s. Davisson’s people, the Esperancians, are an altruistic people who want to help. Van Rijn and Davisson escape in a large groundcar that will keep them alive for months until an Earth patrol can come looking for them. (Van Rijn, however, is appalled to find that the Esperancians do not consider alcohol an essential part of the groundcar’s supplies.)

Buy the Book

The Redemption of Time

Van Rijn refuses to wait for assistance. He discovers that the Ancients, the city dwellers who have dominated the planet by being the only ones who can warn of dangerous solar flares, are behind the attack on the Earthlings. Van Rijn makes contact with the local nomadic hordes, convinces them that the city-dwelling Ancients are out to get them, and whips them into a warlike frenzy. He is perfectly willing to completely disrupt the alien civilization to achieve his goals. As it turns out, due to the alien customs and psychology, his brusque approach proves much more effective than the Esperancians’ altruism.

The third and last story, “The Master Key,” is set in one of van Rijn’s apartments, where the survivors of an incident relate their stories. This setting is a nice change of pace, and gives the story a fresh feel. Per Stenvik has led an expedition to the harsh planet they call Cain, accompanied by Manuel Palomares, a man at arms from Nuevo Mexico. The planet presents some promising trade opportunities, including unique furs and herbs. There are two different intelligent races of Cainites: the Yildivans, and a race that obeys them in some form of servitude, the Lugals. A discussion of religion causes the Cainites to explode into violence, and they wound Stenvik and take members of the expedition hostage. Some truly heroic acts by Palomares result in their rescue, and the nature of the relationship between Yildivans and Lugals turns out to be the key to finding common ground for peace and establishing stable trading relationships.

Final Thoughts

Anderson is a superb world-builder, and his stories are always entertaining. The alien races he invents feel plausible, but uniquely different from the humans with whom they interact. Van Rijn, while sometimes objectionable, is a character the reader will never forget, and he is never boring.

While it is more comfortable to imagine a universe where beings are ruled by, as Lincoln said, the “better angels of our nature,” Anderson’s work stands as proof that a strong case can be made for van Rijn’s philosophy of self-interest and the power of relying on darker motivations like greed.

Now I’m finished with my review, it’s time to open things up for discussion: Have you read any of van Rijn’s adventures, or other tales from Anderson’s Technic History, and what did you think of them? And what are your thoughts on the idea of greed and self-interest as a universal constant?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I’ve never read this series but I would note that Richard Powers might be a better nominee for that cover art than Paul Lehr.

I like some of Anderson’s work (especially his fantasies) but van Rijn is an annoying asshole. And has Poul Anderson ever met a Dutchman? Now, really.

Nicholas van Rijn is fun, if occasionally problematical. He’s sort of a cross between Harry Mudd and Hercule Poirot, and I always imagine him played by John Rhys-Davies.

Many years ago, when I was a callow youth, I truly enjoyed the van Rijn books. Van Rijn was, to me, a basically good guy who was good at solving problems with minimal violence, a rarity for much sf. Like a lot of sff, Anderson less many than others, van Rijn hasn’t aged well.

Anderson always seemed less in one’s face with politics in his books than others, like RAH. After working in industry for a few decades, I’ve gained quite a lot of ambivalence for how for-profit entities actually function. Certainly, the idea of a high level executive, like van Rijn, swanning about shooting troubles has been severely deprecated, as has the idea of efficient, merit -based corporate bureaucracies.

I reread Satan’s World a while back. Alas. I was struck by how casually the traders violated local laws. Also by the fact van Rijn and company were laying the foundation for the events of The Star Plunderer, not to mention the long running rivalry between Terra and Mersia. One might even argue that the Long Night can be blamed on David Falkayn and his pals….

Andre Norton’s two series “Time Traders” and “Solar Queen” are another example of characters using trade in time and space.

I reread the Solar Queen stories not so long ago. Did they ever manage to fulfill any of their contracts? They had the worst luck.

@6: Oh, yes, did Falkayn ever screw up when he encountered the Merseians. He got them out of that supernova mess, yes, but I’m surprised they didn’t hate humans even more after how he did it.

I think that every being that has goals of its own, has goals of its own. If, in all the vast infinity of the universe, two such entities have different goals, they can ignore each other, fight, or trade. Which option is for the best?

To put it another way, you would probably benefit more from encountering the Ferengi than the Federation, let alone the Klingons.

Greed and self-interest at least have the advantage of reliability. Your partner in trade – or any other enterprise – may well lose interest in many motivations that so far have underpinned relationships, but these two are unlikely to change much.

I read these and other van Rijn stories in Astounding and Analog. They were fun, but don’t hold a candle in my view next to his far gloomier Dominic Flandry stories.

My favorite Victorian explorer/writer, Mary Kingsley, once told a lecture audience “there is something reasonable about trade to all men… when you first appear among people who have never seen anything like you before, they naturally regard you as a devil; but when you want to buy or sell with them, they recognize there is something human and reasonable about you.” I agree with Anderson that trade is a pretty universal way to establish friendly relations between cultures — but I don’t agree that that’s an endorsement of libertarian capitalism, because that trade can take a variety of different forms and have a range of different meanings to the cultures doing the trading.

In some cultures, the symbolic value of trade to demonstrate diplomacy and goodwill has outweighed any capitalistic profit motive; e.g. in Imperial China, it was a point of pride for China to give away more than it got in its trade deals, as a demonstration of its superior prosperity and power. And in many Native American cultures, maintaining trade was seen as a gesture of peaceful intentions to one’s neighbors even if there was no real economic benefit (which led to misunderstandings when European settlers cut off trade for strictly economic reasons and didn’t realize it would be taken as a sign of hostility). So in those cases, trade wasn’t even about greed or self-interest. It was often desirable to give more than you got, because the intangible benefit of maintaining good relations or asserting your cultural pride was seen as more important than the material benefit of the actual items being traded.

Heck, even capitalism isn’t really supposed to be about greed. It’s about the continuous movement of capital from one entity to another, the working fluid of the economy. When too much capital gets hoarded by a rich few rather than invested back into the economy, then the economy doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to. Which is why libertarianism is crap, because it has no incentives for people to give a damn about the larger system, so they only care about their self-interest even if it screws things up for everyone else.

@13 “Libertarian capitalism” would seem to require a belief, not that trade is good, but that every relationship other than trade is evil. Something of a leap in logic.

Well, that is what the official truth used to be. It was also an official truth that everyone on Earth was a subject of the Emperor. The official truth should probably be taken with a grain of salt. If it comes to that, I would probably be a bit suspicious of people who suddenly cut off trade relations while claiming to have no hostile intent.

@14/ad: Yes, of course it was the Emperor’s position that all others should be his subjects, but the point is that smart foreigners could turn that to their advantage, because all they had to do was pay token obeisance and the Emperor would lavish them with profit. European emissaries, with their typical ethnocentric arrogance, stubbornly refused to kowtow and thus cheated themselves out of the rewards that would come from a little harmless humility. You don’t have to believe someone else’s point of view in order to recognize how it shapes their choices and figure out how to respond appropriately.

@14 (ad), @15 (ChristopherLBennett)

Right now, I’m listening to the History of China podcast. On more than one occasion a treaty between China and (usually) “northern barbarians”) has involved China sending tribute and still ending up with a huge balance of trade advantage because the northern barbarians ended up buying quite a lot of luxury goods and staples from China.

@14 (ad),

Libertarianism requires two things: some powerful entity to fairly enforce contracts (one would usually call that “a government”) and entities who behave with perfect propriety instead of like, oh, crime bosses or feudal lords.

@1 You may be right about Richard Powers.

@12 I also prefer the Flandry stories. And the David Falkayn stories as well, for that matter. I never warmed to Van Rijn. In fact, in the middle story, Joyce finds Van Rijn’s schtick offensive, which I kind of liked, as she was thinking what I was. I could understand her learning to respect his competence, but was a bit disappointed when she warmed to him as the book went on. But whatever you think of the character, he was always in the middle of a fascinating story.

@15, Nothing arrogant or ethnocentric about demanding ritual submission from everyone. Nothing offensive in that at all. Sure.

It was by reading Poul Anderson that I got interested in reading Rudyard Kipling. That third story in particular is highly reminiscent of Kipling’s work.

@18/roxana: Of course it was arrogant and ethnocentric, but that doesn’t mean we’re not allowed to discuss it objectively as a historical process and examine how other cultures were able to make the best of it. It would be idiotic to suggest that historians are only allowed to talk about the nice stuff, because there isn’t really a whole lot of that in the history of global politics and governance. History is full of injustices, but it’s also full of people adapting to them and finding ways to thrive in spite of them. Most any historical process or event, most any culture or institution, is going to have a mix of positive, negative, and neutral elements, and they’re all important to explore and put in context.

@18, @20

China’s influence was spread with a mix of nominal suzerainity, conquest, and being conquered — they were fairly effective at converting foreign invaders into Chinese. As conquerors, they were no better, and sometimes worse, than the Europeans of the 15th through 20th Century.

History shouldn’t be sanitized, nor should one group or another be especially demonized.

@21/swampyankee: Exactly. Empires are empires. Chinese, British, Roman, Assyrian, Aztec, Ottoman, Songhay, Mughal, whatever, they’re all about the few lording it over the many. It makes no sense to say that one culture’s imperialism is uniquely worse than any other’s. History is about understanding the processes of the past, positive and negative alike, so that we can strive to avoid our ancestors’ mistakes in the future.

@19 I agree that the third story evokes Kipling, and other tales of his era. The premise of sitting around one’s parlor and talking about past adventures is very much of that time.

I’m currently editing a five-volume series featuring all the van Rijn/Falkayn & crew stories for French publication. Volume 4, “Le Monde de Satan” (including “Satan’s World” and the novelette “Lodestar”) is just out, and I’ll soon tackle the fifth and final volume, “Mirkheim”. For some thoughts about this series, I recommend you seek out Poul Anderson’s essay, “Concerning Future Histories”, published in a special Future Histories issues of the “Bulletin of the Science Fiction of America” (Vol 14, # 3, Fall 1979). Reading this, I realized he was a lucid libertarian: the free trade society he imagined couldn’t last and he knew it. Yes, van Rijn and Falkayn sometime had to go for the lesser evil, but the long-term consequences of their actions could be dreadful.

I read all those stories the better part of 50 years ago, and quite enjoyed them. I would likely still enjoy them, as well as his other books (FIRE TIME was a moving story, as I recall). A half-century of experience, including a career as a Naval Officer and an MBA has made me skeptical of Libertarian Economics and Political Theory. Part of the problem is that in an unregulated or loosely regulated environment, violence is almost always the cheapest commodity that can used to improve Return on Investment. History is pretty clear that if one side has enough of an advantage in weapons technology, and they aren’t constrained by someone at least as powerful, they will use violence to improve their position, with activities ranging from raiding and pillaging to conquering and/or enslaving.

But in any event, they were fun books.

@25/Mike Brennan: One of Larry Niven’s Known Space stories, “Cloak of Anarchy,” in which the robot drones that prevent violence in an otherwise “anarchic” park are sabotaged so that true lawlessness results, is an excellent illustration in microcosm of how an unregulated, totally “free and equal” system quickly degenerates into mob rule and the subjugation of the majority by the strongest few. I think it pretty much showed where Niven stood on the whole “libertarian” question.

“It makes no sense to say that one culture’s imperialism is uniquely worse than any other’s”

I’d say that people who cut off other people’s hands for not bringing them enough gold (Columbus, Leopold) have a fair claim to being at the worse end of the scale.

How about people who cut out the hearts of war prisoners?

…and maintain neighboring countries as nominal enemies so they can get those captives

The idea that greed and self-interest will be universal is dubious. The economic model for Anderson’s polesotechnic league seems to be very eighteenth century as practised by the Dutch and British East India Companies. With trades goods consisting of species, liquors and furs! I can see what Anderson was trying to do was invent a conventional fictional universe where his characters could use this as a springboard for the action of their plots. To do that he borrowed from the past. Not so it’s not real or even plausible economics. Greg Costikyan wrote about interstellar trade in his article, appropriately named, “The 11 Billion Dollar Bottle of Wine”. Admittedly this focused on sublight travel, but if faster-than-light travel ever existed it would still be extremely expensive and probably comparable in cost to sublight travel. I suspect interstellar trade would be based on ideas and intellectual property. A much more civilized process and less likely to lead to adventure plots. Poul Anderson’s traders to the stars stories will be seen as artifacts of a business-focused culture.