Harry Clement Stubbs was born May 30, 1922, a century ago, more or less (or exactly, if you’re reading this on May 30th). Readers of a certain age know him as the science fiction author Hal Clement. Younger readers may not know him at all, because Clement died on October 29, 2003, and death often confers obscurity. Which is too bad, because younger readers are missing out on some fine stories. Here are five works by Clement that are well worth reading.

Clement was the hard science fiction author, a man who could not look at a phase diagram without seeing the potential for a thrilling adventure story. Furthermore, Clement delighted in The Game: SF authors do their best to present their readers with worlds rich in verisimilitude, while readers in their loveable way point out errors. Clement took corrections in good spirit, but was better than most at avoiding the need for them.

Modern readers may be surprised that military affairs are very nearly absent from Clement’s works. Although he was a WWII veteran himself, having learned to fly before he learned to drive, Clement preferred to focus on human vs nature conflicts over other varieties. The universe is antagonist enough—or at least it was in his books.

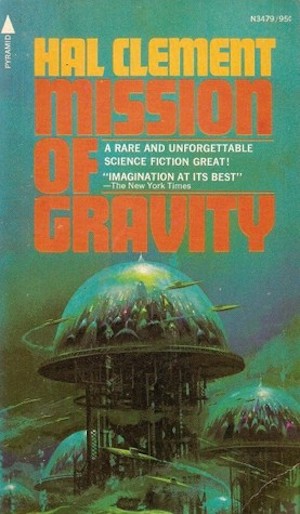

Mission of Gravity (1954)

The planet Mesklin is notable for many things, but two stand out: A) It is an enormous world, sixteen times as massive as Jupiter, and B) its day is absurdly short, just eighteen minutes long. Consequently, Mesklin is visibly oblate, not a near-sphere like Earth, and its surface gravity is unusually variable, from a “mere” three gravities at the equator to hundreds of gravities at the poles.

When a robot probe being tracked by a team of human scientists is lost near one of Mesklin’s poles, it seems irretrievable. Humans may venture with great difficulty to the planet’s equator but to land at a pole is to die. Providentially, however, Mesklin is home to natives who are open to profitable bargains. Barlennan, captain of the trading craft Bree, is quite happy to retrieve the probe in exchange for sufficient payment. It’s just too bad for Barlennan that he does not know Mesklin quite as well as he thinks he does.

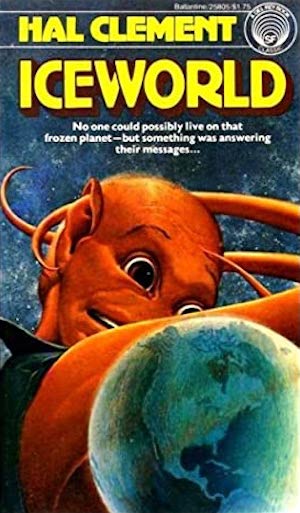

Iceworld (1953)

Sallman Ken, a science teacher from the planet Sarr, is recruited to assist law enforcement in tracking down the source of a troublesome new narcotic plaguing galactic civilization. Very little is known about the substance, save that it is highly addictive and it has to be kept under extreme refrigeration until use. Normal room temperature evaporates the substance almost instantly.

His scientific skills having won him entry into the narcotics ring, the Sarrian teacher discovers that the source of the mysterious drug—tobacco—is a bizarre frozen world where the gaseous sulfur that Sarrians breathe is a solid, a world so frigid that H2O exists in liquid state. A world known to some of its peculiar inhabitants as Earth. However, having made these important discoveries, Ken finds that extracting himself from the gang may be impossible. It’s not that they will terminate him—it’s that he’s been exposed to tobacco. Life without tobacco may not kill Ken, but he may pray for death.

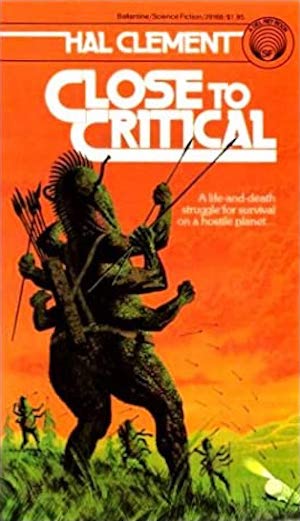

Close to Critical (1964)

Humans and aliens have been content to monitor the planet Tenebra from orbit. Almost thirty times as massive as Earth, with surface temperatures almost 400 degrees Celsius and air pressure hundreds of times that of Earth’s, the planet would kill any exposed human instantly. Even an advanced bathyscaphe would only preserve life for a time. This is no theoretical consideration, for young Aminadorneldo, the son of the ambassador from planet Dromm, and his Terran chum Easy Rich have, though a series of misadventures, become marooned on Tenebra’s surface in such a bathyscaphe.

Thanks to an astonishing lack of ethics, all is not lost. Years before, the orbiting researchers took the opportunity to appropriate native eggs. The hatchlings were raised by a robot to serve the orbiting researchers. Perhaps “Nick Chopper” and his clutchmates can locate and repair the bathyscape in time…unless their odd, robot-raised childhood has left them woefully ignorant of vital, need-to-know information about their home world.

Music of Many Spheres (2000)

Clement got his start in an era when magazines dominated—thus his output consists of a comparative handful of novels and a much larger number of short stories. Short lengths are often ideal for hard SF, as the stories are long enough to convince and succinct enough that errors can’t creep in. Hence the excellence of this collection of Clement’s short fiction.

Music of Many Spheres presents seventeen of Clement’s short pieces. Settings range from Earth to the Magellanic Clouds. Characters range from human to extremely alien indeed. Common to all: Clement’s intense belief in the story potential of physics and chemistry, sciences other authors were often content to overlook.

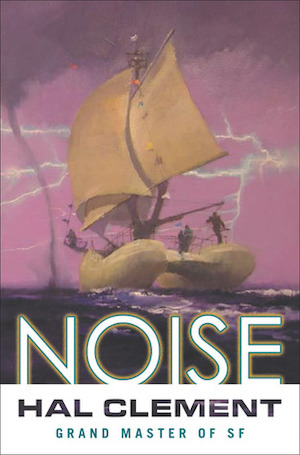

Noise (2003)

Lit by twin red dwarf stars, the close-orbiting worlds Kainui and Kaihapa are home to oceans 2700 kilometres deep. There is no land. No life ever evolved in the twins’ acidic oceans. The dense atmosphere is opaque, frequent thunderstorms jam radio communication, and the solid cores of the planets are highly active. Challenging worlds indeed! But at least the first settlers need not fear being displaced by later waves of colonization.

The Polynesians who settled Kainui brought the tools, in particular wet nanotech known as “pseudolife,” which helps them survive under such challenging conditions. Kainui’s cultures have been content to ignore the rest of the galaxy—and until now, the galaxy returned the favor.

Terran linguist Mike Hoani arrives, determined to document Kainui’s languages. His mission will require him to live as the locals do. Or, if he is foolish or unlucky, to die as the locals do.

***

This is, of course, merely a sampling of Clement’s work. Some of you may have your own favourites, which you can discuss in the comments below. Others who sample the five mentioned above may find them to their taste, in which case I am happy to report that not only is there more Clement out there, a surprising amount of it is still in print.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021 and 2022 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.