Recollections of one of the grand masters of science fiction, on his storied career as a celebrated author and on his relationships with other luminaries in the field. This memoir is filled with all the humor and irreverence Harry Harrison’s readers have come to expect from the New York Times bestselling author of the uproarious Stainless Steel Rat series. This also includes black and white photos spanning his sixty-year career.

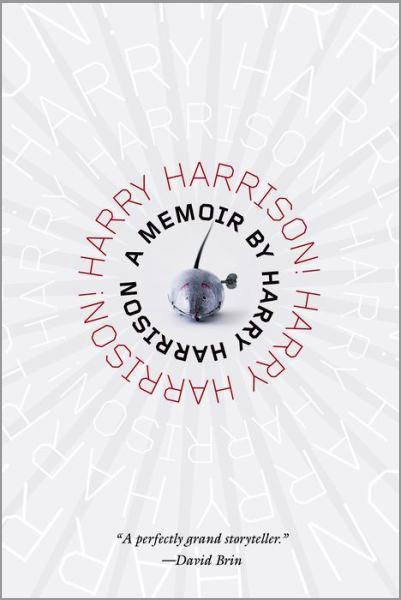

Harry Harrison’s memoir, Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! is available November 4th from Tor Books. Read an excerpt below!

1

My generation of Americans were the first ones born in the New World. Without exception our parents were European—or at the most they were just one generation away from the immigrant ships. My genealogy is a perfect example.

My mother was born in 1882 in Riga, the capital of Latvia, which was then part of the Russian Empire. The family moved to St. Petersburg, where my grandfather worked as a watchmaker. They didn’t exactly flee the anti-Jewish pogroms, but with a keen sense of survival they got out while they were still able. (I remember, as a child, that my mother still used the word “Cossack” as a pejorative.)

My grandfather emigrated first and went to work for the Waterbury Watch Company in Waterbury, Connecticut. Once he settled in and had earned some money he sent for his family, a few at a time.

My father, however, was a second-generation American; his father was born in Cork. Dad was born in the very Irish community in Oneida, New York, in the part of town named the Irish Ridge. This was where the immigrants from Ireland lived when they came to the United States to build the Erie Canal. However his mother was born in Ireland, in Cashel, Tipperary.

In the 1970s, while tracking down my own genealogy and searching for proof of my Irish ancestry in order to gain Irish citizenship, I found that I needed a copy of her birth certificate or other proof of birth. I knew that she was born in Dualla, a suburb of Cashel. After many years in Ireland I knew where to go for local information. All of the medical records had been burned by the British, or so I was told. So I went to the oldest pub—where I bought a round of drinks for the oldest drinkers. It lubricated their memories.

“Moyles—yes, I remember the chap, that printer fellow who moved up to Dublin.” Close. My family on my father’s side were all printers. “Best to talk to Father Kinsella. He’s here every third Sunday in the month.” As the Irish population declined, the priests had to cover more than one parish. Another round of drinks and I had the vital information. On the correct Sunday I visited the good Father, with dire results. He was a tiny man with a white tonsure; his eyes flashed as he pointed to the tottering heaps of air letters. “Americans! It seems they all have grandmothers they’re looking for.…” That was my cue; I jumped to my feet. “I see that you are a busy man, Father. I’m putting twenty quid in the poor box and I’ll be on my way.” Bank notes rustled greenly and the poor of Dualla were that better off.

“What did you say her name was?” the good Father asked. It took five minutes’ time to find Margaret Moyles in the baptismal register, even less to make a copy of her entry. I was sincere with my thanks as I folded it into my wallet. For there, in faded blue ink, in neat Spenserian handwriting, the priest had entered Margaret Moyles, 12 August 1832. All for the price of a few pints. I took that down to the Irish passport office, to the “born abroad” authority, and that was the final piece of paper I needed to get—it wasn’t a European passport in those days, it was a nice green passport with a golden shamrock: it looked like a real passport!

For the record: I was born in Stamford, Connecticut, but grew up in Queens, one of the five boroughs of New York City. My friends were the same as I, a step—or a half step—away from the Old World. Which was something we learned to look down upon as a weakness, not a strength. The Old World was part of the past. Forget that old stuff, we were all-American now (though this made for a linguistic pool that was only appreciated during World War II, when there was never any shortage of translators in the army when they were needed).

My father, Henry Dempsey, started his printing career at the age of five when he began work as a printer’s devil (the lad who opened the shop in the morning and turned on the heater for the diesel engine that powered the printing press). He went on to become a journeyman printer who worked all over the United States and Canada, as well as a quick look-in to Mexico. This history only came out bit by bit through the years.

The story of my name change, however, emerged sooner when I, Sgt. Harry Harrison, veteran of the U.S. Army Air Corps, applied for a passport. My mother showed some understandable discomfort when, most reluctantly, she produced my birth certificate.

The name on it was Henry Maxwell Dempsey. As you can imagine I was most interested in where “Harry Harrison” had come from. In tracking down the history of my name I discovered far more about my father’s life as an itinerant printer than I had previously known. He explained. His family name was indeed Dempsey, but there were some hiccups along the way. It seems he had run into a bit of trouble in Mississippi. At the time he was a journeyman printer, going from job to job. Any town with a print shop and a newspaper welcomed him. Work was never a problem. To get between jobs he rode the rails, in empty boxcars, along with other bindle stiffs—the name for a skilled worker between jobs (as opposed to a regular hobo or bum). This was soon after the turn of the century, with employment very scarce. Riding the rails was an accepted form of transportation for men looking for work.

A lot of my father’s early history I knew. What I didn’t know— with very good reason!—was this missing episode in what certainly can be called a most interesting life.

It seems that the local police in rural Mississippi had rounded up all the itinerant workers from the boxcars of the train, including Henry Dempsey. If you had two dollars or more you were released as a legitimate worker between jobs. My father didn’t have the two bucks so was sent to jail for a year for vagrancy. If this sounds a little exotic to you, think about the reaction of Sergeant Harrison with the strange birth certificate. Of course the whole thing was just a scam for the state of Mississippi to get guys to chop cotton for free. Nice. As my father explained, the end of this particular episode came rather abruptly, when a hurricane hit Mississippi one night. It had rolled up the corrugated iron roof on his barracks and blown it away. The prisoners followed the roof—and my father went with them, vowing never to return to the fine cotton-growing state of Mississippi ever again. And who could blame him?

Later on, after he was married and I was born—and certainly when I was still a baby—he changed his name to Leo Harrison. In those pre-computer days no questions were asked.

Later, during the war, he began to worry about the legality of all this—and was there the possibility that he was still an escaped prisoner? Like a loyal citizen he went to the FBI and told them all that had happened to him. Imprisonment, escape, name change, the works.

They smiled and patted him on the back and thanked him for coming in. And, oh yes, don’t worry about Mississippi, their crooked vagrancy laws had been blown away in court many years previously.

I asked my friend Hubert Pritchard to come with me to the passport people, where he swore that he had known me before and after my father’s name change, when we were both about three years old. No problem. I got a new passport. The story had had a happy ending. My father, the new Henry Harrison, went back to work. But this was all in the future. After years of working all over the country, my father had settled down. He was doing better and earning more money, working now as a highly skilled compositor and proofreader on newspapers—far away from the South. By the early 1920s he was teaching printing at Condé Nast in Stamford, Connecticut.

One of the printers he worked with there was called Marcus Nahan. They must have hit it off and become friends, because it was then that he met Marcus’s wife Anna. She was a Kirjassoff, one of eight brothers and sisters (this family name was an Anglicized version of the Hebrew Kirjashafer, which in turn was a version of Kiryath-Saphir, a town in Israel). All three of her brothers had gone to Yale; all of them became track stars. Louis and Meyer both became engineers. Max went into the State Department and became U.S. consul in Yokohama, Japan—the first Jewish consul in waspland—and was killed in the earthquake there. Most of the sisters had gone to normal school and trained as teachers, except for Rose, who also went into government, ending up in the War Department with the simulated rank of colonel. One of the other sisters, my mother, Ria, also became a schoolteacher. Then, one day, her sister Anna invited her around to dinner.

That my parents met, and eventually married, is a matter of record. What they had in common has always baffled me. My mother was from a family of Jewish intellectuals; five out of her six granduncles were rabbis. My father’s family was middle-class immigrant Irish. (Interestingly enough, almost all my Irish relatives worked in printing or publishing, both in Ireland and the States). Irish working class, Jewish intellectual—only in America.

But meet they did, marry they did, and had a single child. A few years later my father, as we have seen, changed his name and took that of his stepfather, Billy Harrison. (I never met Billy, since he had passed on before I was born. Ironically, he had died of silicosis after many years of sanding wood while working in a coffin factory.) I did meet my grandmother when she came to Queens to visit us. I remember a neat and compact white-haired Irish woman with a most attractive Tipperary brogue. She told me two things that I have always remembered. “Whiskey is the curse of the Irish” and “Ireland is a priest-ridden country.” She had four sons and three died of drink. When I moved to Ireland I had some hint about the priests. After the child-molesting scandals broke, the whole world knew.

Back to history. When I was two years old we moved from Connecticut to New York City. Right into the opening days of the Great Depression, which soon had its teeth firmly clamped onto everyone’s life. Those dark years are very hard to talk about to anyone who has not felt their unending embrace. To really understand them you had to have lived through them. Cold and inescapable, the Depression controlled every facet of our lives. This went on, unceasing, until the advent of war ended the gray existence that politics and business had sunk us into.

All during those grim years when I was growing up in Queens my father was employed at the New York Daily News, or almost employed, since he was a substitute, or a sub. Meaning he showed up at the newspaper at one a.m. for the late-night lobster shift every night, fit and ready for work. He then waited to see if someone called in sick who he could sub for, which was not very often. Then he would return home—often walking the seventeen miles from Manhattan to Queens to save a nickel.

Some weeks he would work only one shift; sometimes none. This meant that there was little money at any time; how my mother coped I shudder to think. But I was shielded from the rigors of grim necessity; there was always food on the table. However, I did wear darned socks and the same few clothes for a very long time, but then so did everyone else and no one bothered to notice. I was undoubtedly shaped by these harsh times and what did and did not happen to me, but it must not be forgotten that all of the other writers of my generation lived through the same impoverished Depression and managed to survive. It was mostly a dark and grim existence; fun it was not.

For one thing we moved home a lot, often more than once in a year, because even landlords were squeezed by the Depression. If you moved into a new apartment all you had to pay was the first month’s rent, then you got a three-month concession. That is, no rent for the next three months. Not bad. Particularly when the iceman, with horse and cart, came at midnight before the third month was up and moved you to a new apartment with a new concession. The iceman received fifteen dollars for this moonlight flit.

This constant moving was easy on my father’s pocket, but hard on my school records. Not to mention friendships, which simply didn’t exist. Whether I was naturally a loner or not is hard to tell because I had no choice. I was skinny and short, first in line in a school photograph where we were all arranged by height. But weight and height did not affect children’s cruelty toward the outsider. I was never in one school long enough to make any friends. Kids can be very cruel. I can clearly remember leaving one of our rented apartments and the children in the street singing—

We hate to see you go

We hate to see you go

We hope to hell you never come back

We hate to see you go.

The fact that I can clearly recall this some seventy-eight years later is some indication of how I felt at the time.

Forced by circumstance, I duly learned to live with the loneliness that had been wished upon me. It wasn’t until I was ten years old that we finally settled down, and I went to one school for any extended length of time. This was Public School 117 in Queens. It was there at PS 117 that I made my first friends.

There were three of us and we were all loners, and as intellectual as you can be at that age. Hubert Pritchard’s father was dead and his mother worked as a bookkeeper at the Jamaica Carpet Cleaning Company to support their small household. Henry Mann, rejected by his parents, was brought up in a string of foster homes. He read the classic Greek and Roman authors in translation. Hubert was a keen amateur astronomer. I was devoted to science fiction. We were all outsiders and got along well together.

Did early incidents in my life cast their shadows before them into the future? Such as the one-act play that I wrote at the age of twelve for our grammar school class Christmas party. I remember very little of it save that it was about funny Nazis (perhaps an earlier working of the plot of The Producers?). In 1937, the Nazis were still considered butts of humor. But I do recall the song Hubert, Henry, and I sang to the melody of “Tipperary”:

Good-bye to Unter den Linden,

Farewell Brandenburg Tor,

It’s a long, long way to Berchtesgaden—

But our Führer is there!

For a nascent playwright this was a pretty poor start; scratch one career choice.

The poem I wrote at about the same time was equally grim. This was published in the PS 117 school newspaper and strangely enough was plagiarized a few years later by a fellow student. He actually had it accepted under his own name, James Moody, for the Jamaica High School paper. I recall the opening lines—which is more than enough, thank you:

I looked into the fire bright,

And watched the flickering firelight…

The shapes of fairies, dwarfs and gnomes,

Cities, castles, country homes…

My career as a poet stopped right there.

After school there was no avoiding the Depression; it was relentless and all-pervading. Pocket money was never mentioned because it did not exist—unless you earned it yourself. I spent most of my high school years working weekends on a newsstand. The widow who owned it knew my mother through the League of Women Voters. Her inheritance had been a wooden kiosk built under the steel stairs of the elevated part of the IRT subway on Jamaica Avenue. It supported her, two full-time workers, and me, working weekends.

Saturday was the busy night when there were two of us there. I sold the Saturday papers, magazines, and racing tip sheets, then unpacked the Sunday sections when they were delivered—all of the newspaper except the news section. When this main section was delivered about ten at night things became hectic, cutting the binding wires and folding in the completed papers, then selling them to the Saturday crowds that were out for dinner or a movie. Carefully counting the delivery first, since the truck drivers had a petty racket holding back a section or two. This continued until about midnight when, really exhausted, I took the Q44 bus home.

Sunday on the newsstand was a quiet day. I was responsible— from the age of fourteen on—for the cash and sales, and quite a variety it was. We sold The Times, the Herald Tribune, the Amsterdam News (a black newspaper—and just a few copies in this part of racially segregated New York). All these were in English. In addition there were two Yiddish papers, Forverts, and Morgen Freiheit, the Italian Giornale, the German Deutsche Beobachter Herald, and the Spanish La Prensa.

The newspapers were very cheap compared to today’s prices. The tabloids were two cents daily, a nickel on Sundays, and The Sunday Times a big dime. However the two racing tip sheets for the horse players were all of one dollar, and I looked on the gamblers as rich, big-time players.

The newsstand job folded—for reasons long forgotten—and was replaced by my golf career. I worked as a caddy at the golf course farther out the island, but still in Queens. Reaching this resort required a bus trip to Flushing, then a transfer to get to the municipal golf course. It was not easy work. You carried the bag of clubs—no wheels!—for eighteen holes for a big buck; one dollar for a day’s hard work. And I never remember getting a tip. The bus fare was a nickel each way and the temptation of a piece of apple pie—five cents in the caddy shack—irresistible after working the round, which meant eighty-five cents for a day’s work.

Money was not easy to come by during the Depression—but a little did go a long way. Saturday was our day off and Hubert, Henry, and I headed for Manhattan, by subway of course. For a single payment of a nickel you had over a hundred miles of lines available. But we headed for Forty-second Street, the hub of entertainment in the city. We even managed to beat the subway fare by using the west end of the 168th entrance to the Independent. This entrance had no change booth but instead had a walled turnstile that was supposed to admit one passenger at a time. However there was no trouble squeezing two skinny kids in, one on the other’s shoulders. Once—with immense effort—all three of us managed to squeeze through at a time; this was not repeated.

Forty-second Street between Broadway and Eighth Avenue had once been the heart of the legitimate theater district—with at least eight venues. The actors left with the arrival of the Depression and the theaters were converted to cinemas. It was ten cents for a double feature—with trailers. Three and a half hours at least; we stumbled out blinking like owls.

The Apollo was our favorite for it only showed foreign language, subtitled films. For budding intellectuals this was a wonderful look into these foreign minds. All of Jean Cocteau, Eisenstein, the best. Then up around the corner of Seventh Avenue was another theater— this one had only Russian films, and it was also very closely observed, we discovered much later. Only after the war was it revealed the FBI had an office there in the Times Building, overlooking the theater, where they photographed all the commie customers.

I had an early file with the FBI! It was a quarter well spent for our day out—a dime for the subway and another for the movie. The remaining nickel went for lunch. You could get a good hot dog for a nickel—or in a grease pit next door, a repulsive dog, and a free root beer. Thirst usually won.

There was, of course, far better food on Forty-second Street—if you could afford it. The best investment was a five-cent cup of coffee at the Waldorf Cafeteria. This admitted one to the busy social life there. In small groups at certain tables, like-minded individuals gathered together. I remember that the communists met on the balcony on the left side—of course!—with the Trotskyites a few tables away. On the right side of the balcony the deaf and dumb got together; dummies as we called them with youthful stupidity. Then, halfway between the two groups were the deaf and dumb communists.

New York was a big, big city and in this house were many mansions.

On the days when we had more than the basic two bits, there were the secondhand magazine shops around the corner on Eighth Avenue. Here, for a nickel apiece, were all of the pulps that cost as much as a quarter on the newsstand. Astounding, Amazing, Thrilling Wonder Stories, all the science fiction mags. As well as Doc Savage, The Shadow, G-8 and His Battle Aces, treasures beyond counting. But I had to count because one of the shops had a terrible and terribly attractive offer. Turn in three pulps—and get another one in return.

So I, in the fullness of time, must have read every SF magazine ever published. Read it and reread it. Then finally—and reluctantly— passed it back for the lure of just one more.…

In addition to the commercial joys of Midtown Manhattan there was, a bit further uptown—and free!—the Museum of Natural History, which contained the Hayden Planetarium. For an amateur astronomer there were delights galore here. There was a class where you learned to make your own reflective lens. The lens tool was fixed to a barrel, while a second glass blank was moved across it as you slowly worked around the barrel. With patience enough, grinding powder, and time, you ended up with a good lens that was still spherical. Then the careful slow lapping to turn it into a parabolic cross section, to be followed by silvering. If you did your work well you ended up with a parabolic lens and you had yourself a telescope, if you could afford the mounting tube and the eyepiece.

I had first started to read science fiction when my father had brought home one of the old large-size issues of Amazing in the 1930s when I was five years old. In the gray and empty Depression years the science fiction magazines rang out like a fire bell in the night. They had color, imagination, excitement, inspiration, everything that the real world had not.

At this same time, science fiction readership was taking on a new dimension. Through the readers’ column of the magazines, readers found and contacted other fans. They met, enthused over SF, formed clubs—on a strictly geographic basis—and SF fandom was born. I, and other local readers, met together in Jimmie Taurasi’s basement in Flushing and wrote a one-page constitution; the Queens Science Fiction League was born. In Manhattan the same thing was happening with the Futurians.

Far too much has been written about SF fandom and this literature is easily available. From a personal point of view it was just a pleasure to meet with other like-minded boys. (No girls! Ghu forbid!) Still in the future were fan feuds, conventions, fannish politics, fanzines, and all the rest of the apparatus of the true fan.

I sink into fanspeak. “Fen” is the plural of “fan.” “Femfan,” a female fan—but they came later, much later! “Ghu”—the god of fandom. “Gafiate”—get away from it all. Leave fandom. And more—a closed society indeed.

From a personal point of view I enjoyed SF and fandom. I went to the first ever world SF convention in Manhattan in 1939; couldn’t afford the nickel entrance fee so had to sneak in. I read all of the magazines, Astounding Science Fiction in particular, and always felt myself a part of the greater whole of SF.

Excerpted from Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! © 2014