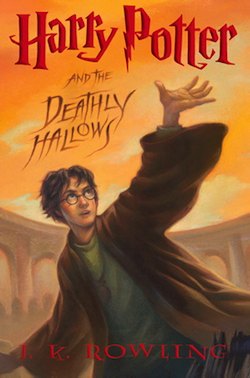

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows had two great challenges to overcome for those of us who read it on the back of the rest of the series.

The first, obviously, was the weight of expectation riding on it as the ultimate Harry Potter volume. Harry Potter was the Boy Who Lived, wizarding Britain’s chosen one. Book seven was always destined to end with a last great confrontation between Harry and Voldemort, a final battle between the Forces of Good and the Legions of Evil, and carrying the finale to a successful conclusion—living up to expectations—was always going to be a tricky balancing act.

The second challenge was Rowling’s decision to move the scene of the action away from Hogwarts. In a sense it’s a natural development: from Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, locations away from the school had become of significant importance. The preceding volumes widened the stage on which the events were set, and by Deathly Hallows, Harry’s growth as a character and Person of Import has advanced to the point where he can no longer act within the confines of Hogwarts, particularly not after Dumbledore’s death. Without his mentor, Harry has to act on his own, from his own resources.

The change of scene robs the narrative of the school year structure, with its predictable rhythms. Stretches of Deathly Hallows suffer from lack of tension and decline in pace, and Harry himself doesn’t seem to do a lot of active protagonising until the final battle. (Drinking game for fast readers: every time someone other than Harry makes a decision, finds a clue, or saves someone’s bacon, drink. Drink twice for someone other than Hermione or Ron.)

When I first read it, I was prepared to mark down Deathly Hallows as quite probably the worst installment of the series. I’ve changed my opinion in the last four years. I still don’t think it’s the best installment in the series—I’m in the Goblet of Fire camp on that one—but it’s definitely not the waste of paper my 2007 self was prepared to shelve it as. For one thing, this is a book with some serious Moments of Awesome.

Let’s start with the one that sticks out first in my mind. It’s less a moment than a single line, actually, the line that kicks off Harry’s hero’s journey as a geographical, rather than an emotional, voyage. Up to now, while Harry Potter was definitely doing the bildungsroman thing, there were always adults present. Perhaps not to be trusted, and certainly not to be relied upon, but always there, at least to clean up the mess afterwards.

From the moment of Kingsley Shacklebolt’s message at Fleur and Charlie’s wedding, that’s no longer true.

“The Ministry has fallen. Scrimgeour is dead. They are coming.”

Our three heroes are—from the moment of Hermione’s quick-thinking escape—cast off on their own resources. This, combined with the growing claustrophobic tension within the wizarding world, the persecution of ‘mudbloods,’ the fascist parallels obvious within the new regime at the Ministry, and Harry’s growing concern about Dumbledore’s biography (and his realisation that his mentor may not always have been such a shining example of the Good Wizard) lends this final book a somewhat more adult cast.

Somewhat. This is still very much a book about growing up, as the quest for the Horcruxes makes clear. Harry and co. are still following the hints and instructions of Professor Dumbledore—though with Dumbledore’s death, Harry is starting to grow out from underneath his shadow and make his own choices.

Oh, those Horcruxes. The search for them gives us some of the best Moments of Awesome in the series as a whole. I’m thinking particularly of the infiltration of the Ministry of Magic, in which Harry, Hermione and Ron go undercover to recover Regulus Arcturus Black’s locket from Dolores Umbridge. During the course of this episode, there’s the wee matter of rescuing a few Muggle-born witches and wizards from the Muggle-born Registration Committee, battling Dementors, and fleeing the Ministry while being pursued—a pursuit which results in Ron’s injury, and weeks spent camping in the woods.

Ron departs from the party due to a very adolescent misunderstanding over Hermione’s affections. His eventual return and reconciliation with both Harry and Hermione is not entirely made of win. But I’ll be honest here: I feel that the middle section of this book really lets down both its beginning and its end, and every time I’ve reread it, I’ve had a hard time not skipping from the Ministry to Xenophilius Lovegood, his story of the Hallows*, and our heroes’ narrow escape from Death Eaters. Now that’s a Moment of Awesome.

*We all know what the Hallows are, and why they’re important, right? Mastery of Death, and all that jazz. Definitely important to your hard-done-by Dark Lord whose ambition is to live (and, naturally, rule) forever. Book seven seems a little late to introduce this as a long-term Dark Lord goal, but I’m not going to argue with the result.

As is the trio’s capture, interrogation at the Malfoy residence, and escape. (I have to say, though, I rather admire Bellatrix Lestrange. That woman might well be Voldemort’s sole halfway competent minion. But I digress.)

The escape from the Malfoys’ results in the first major character death of the novel. While the deaths of Sirius Black and Albus Dumbledore in previous volumes demonstrated that Rowling isn’t shy about killing at need, Dobby’s death—heroic, and definitely moving—is a foretaste of the sacrifices that are to take place during the final battle.

From this moment the pace ramps up, heading down a straight shot towards that conclusion. Our heroes garner another Horcrux from a dashing caper—a raid on Gringotts’ Goblin Bank with Hermione disguised as Bellatrix Lestrange, from which they escape on dragon-back. From there it’s off to Hogsmeade, to find a way into Hogwarts to acquire the last-but-one Horcrux.

In Hogsmeade, rescued from Death Eaters by Dumbledore’s little-known brother Aberforth, Harry finally learns that, in fact, his mentor was far from perfect. It’s a moment of revelation, but also a moment in which Harry steps up. He’s going to keep fighting. To the end.

And about that end—

The battle for Hogwarts is suitably epic, with loss and heartache and triumph and despair. And the life and death of Severus Snape probably deserves a post of its own. But Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows as a whole, I think, stands or falls for a reader on their reaction to the final showdown between Harry and Voldemort. As the conclusion to a seven-book series, it has a lot to live up to, and I’m not entirely sure it does.

Having learned that Dumbledore believed that Harry is one of Voldemort’s Horcruxes, Harry is resigned to dying. So he uses to Resurrection Stone—one of the three Hallows, which Harry has uncovered at the last moment—to talk to his dead parents, as well as Sirius Black and Remus Lupin, before he hands himself over to Voldemort and lets himself be struck with a killing curse.

“Greater love has no one than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.” John 15:13, NIVB.

It’s Harry’s Jesus moment. He dies and rises again, after a conversation with the deceased Albus Dumbledore in a cosmic train station. On one hand, it’s certainly one way to conclude a hero’s journey. On the other, Harry’s survival robs his act of bravery—his act of sacrifice—of much of its meaning.

From this moment, Voldemort is defeated. He just doesn’t know it yet, and his final attempt to take Harry down rebounds upon himself. Ultimately, he’s responsible for his own doom. That seems to me to be the moral of the story, in the end: the good triumph, while the bad ruin themselves.

The epilogue reinforces this conclusion. Life went back to normal, it seems. Nineteen years down the line, all the survivors have their happy endings, and the new generation is all set for their Hogwarts experience. Although it seems to me unfortunate and clichéd that Draco Malfoy, in his corner, never seems to have grown past being an antagonist. Or perhaps that’s Ron, happily passing schoolday antagonisms down to the next generation. Almost everything is neatly wrapped up and tied with a bow.

Though I do wonder whatever happened to Looney Luna.

Deathly Hallows marks the end of Harry Potter’s journey, and the end of the line for the readers who joined him along the way. I never caught the bug in the same way many people my age did, for while I, too, may have been eleven years old in 1997, at the time I was busy devouring Robert Jordan and Terry Goodkind. I didn’t meet Harry until years later, when I came around at last to the realisation that a skinny book can be as much value for money as a fat one. Too late to love uncritically: in time to understand why other people did.

In the decade between 1997 and 2007, Rowling created a story—a world and its characters—that spoke to a generation. Bravery, daring, friendship: a story that combined the fundamentally comforting setting of the boarding-school novel with the excitement and danger of the fantasy epic, a story that mixed the familiar and the strange and produced something entirely new. In a way, the conclusion of that story marked the end of an era.

And the beginning of a new one. For Harry Potter’s success inaugurated a new generation: of teenagers finding it normal to read and talk about reading for pleasure, of adults willing to read YA novels, and of writers and publishers who might just take a chance on YA books with epic scope. That’s not a bad legacy for any series to leave behind.

In fact, it’s a pretty excellent one.

Liz Bourke is a lifelong reader of SFF who also reviews for Ideomancer.com. And yes, she’s looking forward to seeing Deathly Hallows Part II in cinemas. She’s always entertained by explosions.