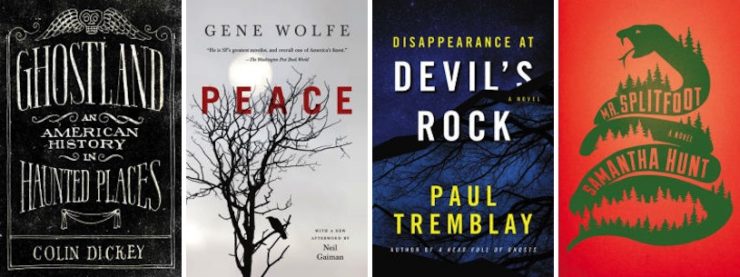

“I spent several years traveling the country, listening for ghosts.” So writes Colin Dickey early on in his recent book Ghostland: An American History of Haunted Places. Dickey’s previous books have explored subjects like grave robbing and religious fanaticism before, and Ghostland falls into the same category: deeply entertaining, evoking a powerful sense of location, and juxtaposing (with apologies to John Ford) both legend and fact. Dickey’s book is structured around a series of profiles of different places, each of them haunted: hotels and mansions and jails, each with their own evocative strains of history.

While Dickey does encounter a few mysterious phenomena, this isn’t as supernaturally-tinged a work of nonfiction as, say, Alex Mar’s recent Witches of America. Instead, his goal is more to examine why we’re so drawn to ostensibly haunted places, and what makes tales of hauntings so relevant over the years, decades, and centuries.

What he finds, by and large, are the restless echoes of various American sins. Frequently, he’ll begin by recounting the folklore associated with a haunting somewhere—and, as Dickey is a fine storyteller, this is often deeply compelling stuff. And then he’ll pivot, revealing the history behind it: that the Winchester Mystery House’s origins are far less Gothic than ensuing stories about it might reveal; or that uncanny tales of dead Confederate soldiers largely originate with the sort of organizations that evolved into racist hate groups in the South. Legends of ghosts frequently mask other, more unsettling, stories—of societal fear of, basically, the Other, the historical crimes that this fear has prompted, and a collective guilt that never quite abates.

For Dickey, the ghost story is but one layer in a larger narrative, one that offers horrors ultimately greater than supernatural manifestations and mysterious sounds in the night. On the fictional side of things, that same concept can be used to memorable effect. Gene Wolfe’s 1975 novel Peace features a narrator who is, to some extent, haunting his own memories, at times consciously entering them and altering them, and in one instance bragging to a figure from his past of his godlike abilities in this state. It’s a jarring work to read: one one level, it’s a kind of Midwestern pastoral work featuring an older man, Alden Dennis Weer, looking back at his long life as his health gradually declines. But there are subtly dissonant hints that there’s more happening here, beyond this seemingly familiar narrative.

Ambiguity looms large here—there have been a number of deep reads of this novel, ones in which brief references turn out to have a significant impact on interpretations of the narrative, ultimately turning Weer from a reliable narrator into a much more diabolical one. Throughout the narrative, Weer becomes a kind of restless and malicious spirit, defying borders of time (and possibly mortality itself) to carry out acts of vengeance and hate—an unsettling magic-realist metafictional poltergeist, a revenant whose hand extends far beyond the pages of this novel. Or maybe not—this is a book that rewards multiple readings, but it’s also one where ambiguity plays a major role.

Paul Tremblay’s Disappearance at Devil’s Rock makes use of a different kind of narrative ambiguity. Certain facts are clear from the outset: a teenager named Tommy goes missing in the woods; his mother and sister detect what may be a spectral presence in their home; and his friends seem to know something more about the circumstances of his disappearance than they’re letting on. There’s a bold contrast set up between certain narrative elements—there’s more than a little of the police procedural here—with a series of fundamentally unanswerable questions. Furthering this mode are Tremblay’s chapter titles, which hearken back to another century’s traditions in their descriptiveness. (Sample: “Allison Driving in Brockton with the Boys, He’s Not Feeling Too Good, Three Horrors.”) Aspects of this book are crystal-clear; others veer into a horrifying place where clarity might never emerge.

Memories, madness, and the possibility of the supernatural all make for questions of reliability and its opposite—one reader of this book might take it as a tale of the grand and supernatural, while another may regard it as a story of a police investigation with some surreal touches. But the deliberation with which Tremblay lays out this story is impressive. The landmark that gives the book its title also plays a role in the narrative, with multiple explanations being offered for how exactly it got its moniker. The sections in which Tremblay dissects the possible roots of “Devil’s Rock” play out like a fictionalized version of the narrative devices in Ghostland. Here, too, the crimes of the past aren’t far off, and the presence of restless spirits might well signify something much worse.

Ghosts and layers and mystery wind together in unexpected ways in Samantha Hunt’s novel Mr. Splitfoot. In it, she weaves together two parallel stories: one of a young woman named Ruth, raised in a cultlike environment, who ends up involved in a plan to fake a series of seances; the other follows Ruth’s niece Cora, who ends up accompanying Ruth on a walk across much of New York State several years later. Ghosts, both literal and metaphorical, are a constant presence in this work, though it’s only by the end of the novel that its true shape is fully revealed.

Hunt, too, has dealt with this sort of supernaturally-tinged ambiguity in her fiction before. Her novel The Seas featured a main character who may or may not be one of the merfolk, and The Invention of Everything Else posited one of its characters as a time traveler, leaving it unclear for a long stretch of the novel if he was the genuine article or more disturbed than anything else. And for all that the supernatural is one element here, it isn’t the only one, nor is it the most menacing. Readers will find descriptions of institutional failure, religious fanaticism, misogyny, abuse, and controlling behavior beside which being haunted by someone’s restless spirit sounds downright pleasant.

We all carry our own ghosts with us, these books suggest—both ghosts that reflect aspects of our own personal history and ghosts that have amassed through the bleaker aspects of our societal history. And as disparate as these works might be, they all point to one conclusive course of action: pulling back the layers to find the roots of these hauntings, seeing them for what they are, and doing one’s best to understand how they came to be.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).